Forest, Tower, City: Rethinking the Green Machine Aesthetic

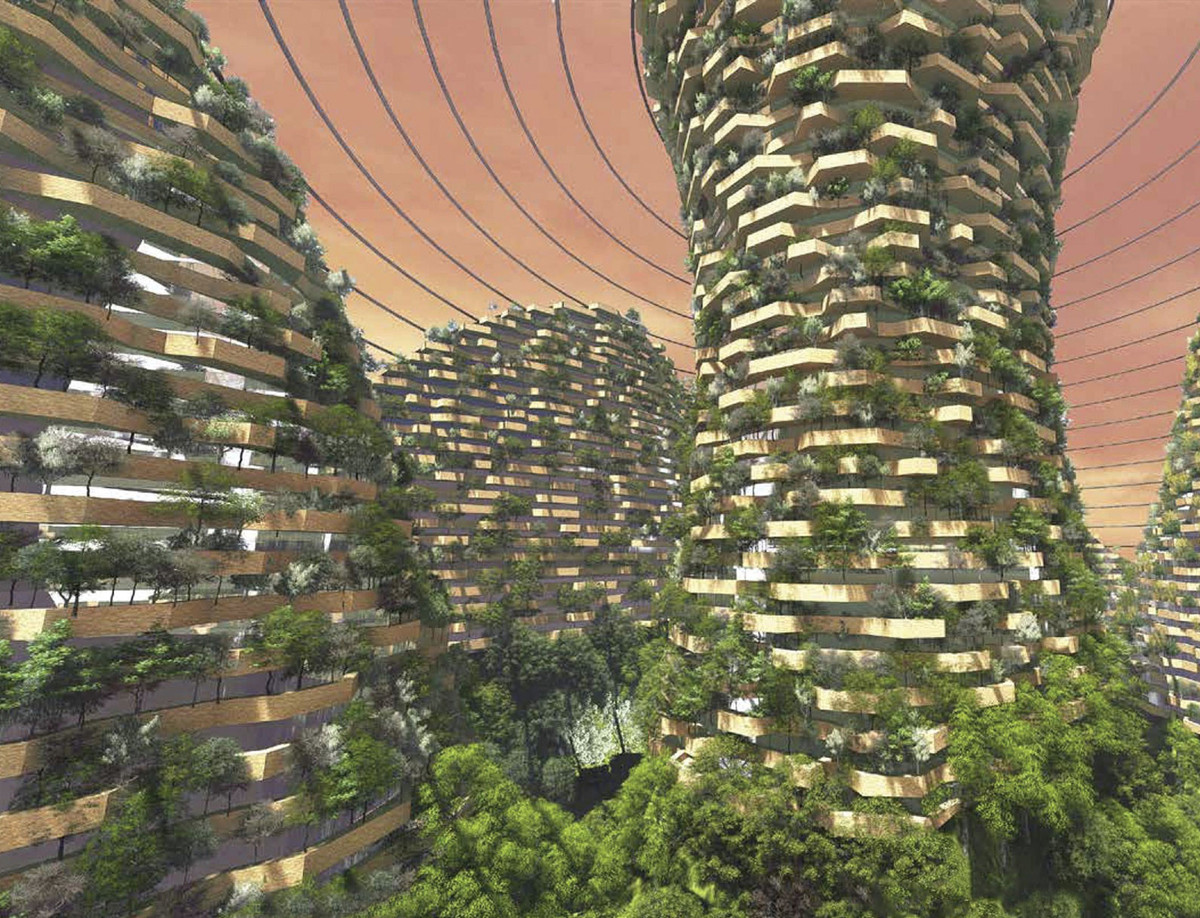

In many ways, the forests of Stefano Boeri’s Bosco Verticale towers in Milan (2009–2014) are both lovely and functional. Boeri and a coterie of consultants took an idea that might seem fanciful and cliché and, through diligent and years-long attention to the minutiae of the structure and the specifics of airborne trees, produced a working prototype. The seed has been planted, and Boeri has been propagating it in cities throughout Europe and Asia. The towers undergird proposals of a more sweeping scale, such as his design proposal for a Forest City in Shijiazhuang, China (2015). Boeri’s vertical forests stand among a distinct, albeit not altogether new, building type of the early 21st century: the eco-fantasy project. Historical projects range from work by Ken Yeang to Emilio Ambasz, but one could also reference Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners’ (RSHP) proposal for a 200-meter-high tower on Park Avenue (2012–2015), which included a series of “sky gardens” that were imagined to “reconnect workers and the city with nature,”1 and Sasaki Associates’ Forest City Master Plan (2015), which envisions a $100 billion development on an aquatic reserve off the coast of Malaysia and “seeks to establish a symbiotic relationship between development and the natural environment.”2 Large-scale, ambitious projects such as these have not just attempted to mitigate a building’s impact on natural systems, but have sought, at least rhetorically, to become a part of those systems.

The rhetoric surrounding these purpose-grown forests is that of performance and optimization. For example, RSHP’s sky gardens proposed to employ “different American landscape ecologies, from forest to alpine, to suit the different altitudes of each garden,”3 and the trees of Boeri’s vertical forests are selected at each level and exposure for the seasonally specific solar shading they can provide. These trees protect interiors from wind, small dust particles, and acoustic pollution, while releasing humidity and oxygen and absorbing carbon dioxide. In a description in this magazine, in 2009, Boeri refers to the forested facade as a “comfort-creating ‘mechanical’ device,” referencing critic Reyner Banham’s assertion in The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment (1969) that humans need the comfort and environmental control that can be provided by mechanical systems, with their capacity to create, as Boeri quotes Banham, “dryness in rainstorms, heat in winter, chill in summer.”4

The forest is thus mobilized in the service of a building’s (or city’s) environ-mental performance and justifies its centrality to the project with reference to the energy saved and the carbon sequestered. Setting aside questions about the degree to which these trees perform to the allocated specifications, another concern arises: When a forest is designed to perform in a highly specific way, it becomes the purview of experts. When a living system falls under the management of a cadre of experts, it ceases to be the responsibility of the forest’s cohabitants—the citizens, occupants, and tenants of the forest towers and cities.

Experts in high-altitude pruning keep the Bosco Verticale carefully trimmed; experts in soil nutrients and plant survival developed the trees, selected the species, and engineered their soils; experts in wind forces ensured the trees would stay put; experts in irrigation systems monitor and tune the automated irrigation; experts in building systems ensure that the system is performing as it should. At the Bosco Verticale, the thick, occupiable facade that contains the forest are not part of the resident’s property—they are common amenities, like the lobby, and care for these areas is managed by a centralized maintenance contractor in consultation with the landscape architect. Thus, the occupants of the towers are surrounded by the forest, but legally isolated from it. Like a complex HVAC unit that keeps the occupants comfortable but otherwise remains alien to them, the forest is delimited as explicitly neither a matter of concern nor care for those who live closest to it.

Of course, it is nothing new to conceive of forests as solely the province of experts, to require that they perform in particular ways, to deliberately select and combine (and improve) tree species for these performances and—when the trees fail to thrive—to offer compensatory soil nutrients or carefully engineered ecosystems. The emergence of scientific forestry as a discipline also ushered in the transformation of the forest-as-resource into forest-as-system—albeit a system for the production of a resource. This forest-as-system first needed to be simplified and quantified before being subsequently managed and manipulated.

The Normalbaum, or standard/average tree, was one of the first conceptual tools used in calculations of wood volume as early foresters sought to determine the accurate value of any given forest.5 Calculations of a previously unfathomable complexity were performed in order to estimate what the annual volumetric yield of a forest could be if it were to be able to provide a continuous supply of wood. This and similar skill requirements of the woodsman gradually ensured that forest experts only saw and thus only valued what was calculable. The mathematical abstraction of the Normalbaum slowly became a grown reality as the well-managed forest took on its scientific form: evenly aged trees of a single species were planted in neat rows. Gone was the seeming chaos, incalculability, and ultimate unknowability of the forest, replaced with well-organized wood matter, awaiting use by humans.

The mediation of nature by expertise is a familiar story, but one that bears more weight in the contemporary context of eco-modernists and green capitalism. As theorist Donna Haraway has written, “it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with.”6 These high-tech eco-towers and eco-cities are visions of a future imagined as coexistence and connection with the natural world, but they are undergirded by another story, an Enlightenment conception of nature, and of forests specifically, as a resource to be optimized, scientifically managed, and administered by experts in order to enable dense settlement, nation-building, and maintenance of the population. This centuries-old story has been an important one, with far-reaching historical resonance: ideas about resource stewardship that we now identify with sustainability first arose in the Western world, by many accounts, within early forestry.7 But, innovative thinking, in architecture and elsewhere, about forests and our potential relationships to them has evolved in the last 250 years. We now know that trees collaborate and communicate with one another via complex underground networks of roots and mycelium, swapping nutrients and minerals and helping members of the tree community most in need.8 We have also, for decades now, become increasingly aware of the instabilities in the carefully constructed distinctions between humans and the rest of the living world, circling around a sort of species exceptionalism that appears to be mostly hubris.9

If the forest is a mechanical system, is it still a forest? Can we ask of architecture a capacity to move beyond conceptions of nature as system and resource? What if the efforts of our most imaginative, productive, and convincing thinkers and designers, a category to which Boeri, RSHP, Sasaki Associates, and many others proposing these eco-fantasies surely belong, were mobilized toward more humble efforts than the proliferation of more towers on newly developed land and the instantiation of entirely new cities? In other words, can the forest serve not as a facilitator of developer logic but as a conceptual buffer that disrupts and reimagines relationships between social and biotic systems? These projects position the forest, often explicitly, as a one-to-one replacement of wild or potentially rewilded land given over to development. The visually seductive imagery of urban life in a forest city serves primarily to arrest reflection on whether a brand new city, district, or tower is the most ecologically sound choice. In many ways, the forest city has replaced the zero-carbon city of a decade ago as the eco-cloaking device for mass construction. But the plans for Shanghai’s zero-carbon city, Dongtan (begun 2005), were long ago abandoned, and Abu Dhabi’s Masdar City (begun 2006) lies half-constructed and mostly deserted. The vertical forests indicate hopeful aspirations for living differently relative to environmental patterns and environmental knowledge, but their realizations remain largely superficial. The architectural challenge—the global cultural challenge—is to imagine living with a forest that somehow exceeds both nostalgia and instrumentality. It is a difficult goal, one requiring a new orientation to architecture and its relations.

Trees are being leveraged here in the service of a slightly updated rhetorical maneuver, in which it is claimed that the managed forest is somehow not new but part of what was already (or could have been) there. Maybe we can aspire instead to produce architectural visions that help us imagine forests and trees as a “community to which we belong”10 rather than systems to be exploited. Could high-profile eco-projects instead question the insatiable drive for newness and bigness and enable emerging conceptions of the members of the vegetal realm as irreducible, incalculable, and unsystemetizable . . . yet utterly essential?

1 Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, “425 Park Avenue,” https://www.rsh-p.com/projects/425-park-avenue/.

2 KS Wong, “Forest City: A Property Developer’s Vision Becomes Reality,” Forbes Custom, December 12, 2016, http://custom.forbes.com/2016/12/06/forest-city/.

3 Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, “425 Park Avenue.”

4 Stefano Boeri and Francisca lnsulza, “The Vertical Forest and the New Urban Comfort,” Harvard Design Magazine 31 (Fall/Winter 2009): 60.

5 See Henry E. Lowood, “The Calculating Forester: Quantification, Cameral Science, and the Emergence of Scientific Forestry Management in Germany,” in The Quantifying Spirit of the 18th Century, eds. Tore Frängsmyr, J. L. Heilbron, and Robin E. Rider (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 329–42.

6 Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 12.

7 See David A. Perry, “The Scientific Basis of Forestry,” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 29 (November 1998): 443.

8 See Suzanne Simard, “How Do Trees Collaborate?” TED Summit lecture, June 2016, presented via TED Radio Hour on NPR, 18:19, January 13, 2017, https://www.npr.org/2017/01/13/509350471/how-do-trees-collaborate.

9 See, for example, the works of anthropologists Philippe Descola, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, and Eduardo Kohn.

10 Aldo Leopold, “Forward” in A Sand County Almanac (1949; repr., New York: Random House, 1986), xviii–xix. Full quote: “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect. There is no other way for land to survive the impact of mechanized man, nor for us to reap from it the esthetic harvest it is capable, under science, of contributing to culture.”

Daniel A. Barber is assistant professor of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. He researches the historical and contemporary relationship between architecture and global environmental culture. His book A House in the Sun: Modern Architecture and Solar Energy in the Cold War was published in 2016; Climatic Effects: Architecture, Media, and the Planetary Interior is forthcoming in 2019. He edits the Images of Accumulation series on e-flux Architecture.

Erin Putalik is an architect and a doctoral candidate in architectural history and theory at the University of Pennsylvania. Her dissertation examines the relationships between architectural experimentation with newly developed wood materials, emerging resource conservation ideas, and scientific forestry practices in the early 20th century. She currently teaches architectural design and history at the Rhode Island School of Design.