Kiss Nature Goodbye

Hats off to commodity culture. The endless quest for new products has spawned another hot-selling hybrid: the not-entirely-entertaining, but not-really-educational, simulated “natural” attraction. At the Mall of America, it’s called UnderWater World. You pay $10.95, go down the escalator, and enter a dark chamber where synthetic leaves in autumnal tints rustle as you pass. You’re in a gloomy boreal forest in the fall, descending a ramp past bubbling brooks and glass-fronted tanks stocked with freshwater fish native to the northern woodlands. At the bottom of the ramp, you step onto a moving walkway and are transported through a 300-foot-long transparent tunnel carved into a 1.2-million-gallon aquarium. All around you are the creatures of a succession of ecosystems: the Minnesota lakes, the Mississippi River, the Gulf of Mexico, and a coral reef. You’ll “meet sharks, rays, and other exotic creatures face to face.” Sound like fun? Call 1-888-DIVE-TIME (no kidding) for tickets and reservations.

Marketing the Great Outdoors

By itself, UnderWater World won’t rock the planet. But if not particularly significant, this piece of concocted nature is emblematic of a larger phenomenon. I refer to the growing commodification of nature: the increasingly pervasive commercial trend that views and uses nature as a sales gimmick or marketing strategy, often through the production of replicas or simulations. Commodification through simulation is most obvious in the “landscapes” of the theme park and the shopping mall. Such places have been widely discussed of late: the malling and theming of the public environment and the prevalence of simulation as a cultural form have elicited skeptical commentary from, among others, philosopher Jean Baudrillard, architectural historian Margaret Crawford, essayist Joan Didion, novelist and semiologist Umberto Eco, design critic Ada Louise Huxtable, and landscape designer Alexander Wilson.1 Readers of cultural criticism are generally familiar with these writers and I won’t rehearse their arguments. Rather I want to put a different spin on the problem, one attuned especially to the landscape.

Specifically, I am interested in how the commercial context is modifying our conceptions of nature—changing the cultural meanings and values of nature. While many observers focus on the more outrageous examples of malling or theming—the many mutations of Disneyland, Universal City Walk in Los Angles, the various metropolitan simulacra in Las Vegas—I want to explore how nature is packaged for consumption in more ordinary places: first, in our local malls; and second, in nature-based theme parks. The phenomena that are changing—even distorting—traditional conceptions of nature are not limited to a few flagship sites but rather are pervading our surroundings. Almost everywhere we look, whether we see it or not, commodity culture is reconstructing nature.

This is not, however, another requiem for lost wilderness. We humans have always modified our landscapes—sometimes for better, sometimes for worse. Nature shapes culture even as culture inevitably alters nature. Nor is this a lament for some more “authentic” version of nature. The membrane separating simulation and reality is far more porous than we might want to acknowledge. For at least five centuries, since the 15th-century Franciscan monk Fra Bernadino Caimi reproduced the shrines of the Holy Land at Sacro Monte in Varallo, Italy, for the benefit of pilgrims unable to travel to Jerusalem, replicas of sacred places, especially caves and holy mountains, have attracted the devout. In the United States, simulations have featured prominently in entertainment landscapes: the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, to name just one gaudy example, included a scenic railroad whose route featured fabricated elephants, a replica of Yellowstone National Park complete with working geysers, and a mock-up Hopi village constructed by the Santa Fe railroad. But if simulations are not new, they have, in recent decades, become almost ubiquitous, and increasingly they are being used for commercial purposes. And this raises an important question: what does it mean when nature is for sale at the local mall or the downtown boutique? Is this beneficial or harmful? Perhaps it is time to abandon at least some of our ideas about nature—Nature with a capital “N,” imagined as independent of culture—and to take the measure of the new “nature” we have been creating.

Why should the commercial landscape matter to designers and those concerned with the designed environment? Partly because there is much room for improvement in this commercial landscape: such places might benefit in interesting ways if the familiar landscape types, the park and the garden, were expanded to encompass the food court, the parking lot, and the flood-control sump hole. It also matters because the commercial landscape is an embodiment of demographic trends that cannot be ignored. Over the past few decades, as suburbia has become more politically and culturally dominant, shopping malls have become one of the centers of our culture. Far more than shopping happens there: malls have usurped many public functions; indeed they have challenged prevailing ideas of “public space”—malls are ersatz town centers, with police stations, registries of motor vehicles, satellite educational institutions. They have even been venues for weddings (convenient, no doubt, for those last-minute gifts). But of course, they are not really civic spaces; these privately owned emporia encourage discreet forms of economic exclusion and social regimentation. As entertainment and tourist landscapes, they are open only to those who can pay. As private places, they limit freedoms of speech and assembly. The Mall of America, for instance, enforces a curfew—those under sixteen must be accompanied by an adult on weekend evenings; everyone under twenty-one must carry government-issued photo identification.

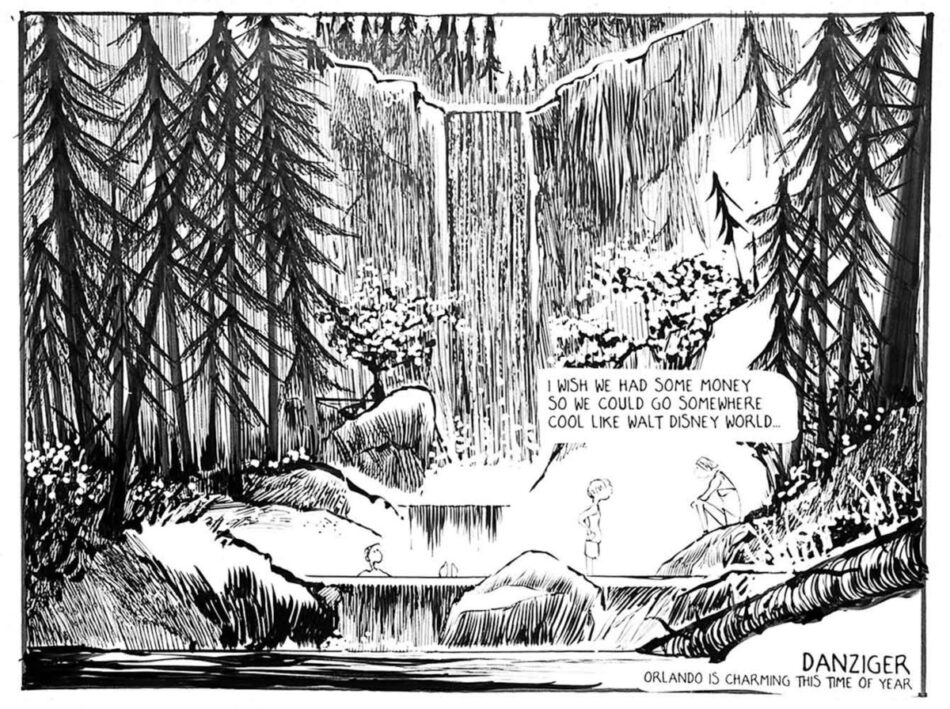

Yet malls are wildly popular and increasingly the locus of our leisure activities. The Mall of America claims to be the “most visited destination” in the United States, annually attracting more than 40 million visitors. On the regional scale, Potomac Mills, an outlet mall in northern Virginia that receives 23 million visits a year, is now the number-one attraction in that state, outpacing even the Civil War battlefields, Colonial Williamsburg, and amusement parks like Busch Gardens and Paramount’s Kings Dominion.2 Malls feature entertainment and recreation for children and adults, ranging from multiscreen cinemas and video-game arcades at local malls to full-scale enclosed amusement parks like Camp Snoopy at the Mall of America. Almost everywhere, pay-for-play is available in some form: one can play indoor miniature golf, climb synthetic rock walls, face down foes in games of laser tag and in virtual-reality intergalactic battles. Who needs a park—one of those places with grass and trees, playgrounds and benches—when you can while away a Sunday afternoon in a safe, sanitized, and economically segregated simulation of a public space?

How exactly is nature constructed in these new commercial places? When we shop at stores like the Body Shop and the Nature Company, we receive whole sets of messages about nature. At the Body Shop, “natural essences” are linked to physical, emotional, and economic personal fulfillment. The customer here is flattered: the pampering provided by natural oils and aromas is a reward for worldly success; nature here is understood as a source of products that makes you feel good rather than as a primary and complex phenomenon for which one bears personal and social responsibility. At the Nature Company, thousands of goods from stuffed tigers to geodes, from bird feeders and wind chimes to field guides and wildlife videos, have the effect of condensing space and time. The nature presented in this chain store is not localized, dynamic, and differentiated into various ecosystems, but homogenized, static, portable, and consumable. The Nature Company implies a kind of global-scale bricolage, a grab bag of concoctions from who-knows-where, the whole assortment saying little about the actual places from which these products originate. Rather, the goods speak tellingly about those for whom they are marketed—about affluent people who enjoy nature in their spare time, who care about nature and want to be surrounded by things that express their concern. What is really available at these stores, however, is not on the shelves: in a sense, the chief product of the Body Shop and the Nature Company is irony, albeit unintended. These boutiques promise to help us get in touch with nature, but instead they effectively remove us from it—instead of being outside enjoying nature, we’re at the mall buying products that express our love of nature.3

The larger environment of the mall likewise exploits our affection for nature in order to soothe us in the act of consumption. At most malls, plants are scattered around liberally, especially in the food courts; of course, this indoor profusion compares tellingly with the typical mall exterior, whose gray banality makes the indoor embellishments seem all the more lush. And at some malls—Potomac Mills, for instance—the presence of real plants is supplemented by videotaped nature: large monitors hung at regular intervals in the corridors of Potomac Mills show images of forests and waterfalls. And the entrance to Montgomery Mall, also in suburban Washington, features a large mural of the kind of pastoral scene once characteristic of Maryland. The mural even includes trompe l’oeil binoculars—a device you can’t use to gaze on a landscape that’s no longer there.

Nature at the mall can be understood as using the idea of “adjacent attraction,” as this has been described by Richard Sennett and Margaret Crawford. Adjacent attraction refers to the phenomenon by which unlike objects, removed from their ordinary circumstances, reinforce each other’s value—in other words, if you see something that usually makes you feel good, you might also feel good about whatever happens to be placed next to it. Seeing something unexpected, out of context, makes it seem unfamiliar and therefore exotic, stimulating.4 Nature at the mall is just such an unexpected phenomenon. The marketing logic is clear: if the customer likes nature, the customer will like the mall and want to shop. Moreover, the demographic group that likes nature most is precisely the affluent group these malls are striving to attract.

In a growing number of malls across the country and around the world, you will now encounter a themed store and restaurant called the Rainforest Café. Billed as “a wild place to shop and eat” and “an environmentally conscious family adventure,” the Rainforest Café is one of the more pointed instances of how commercialized mass culture is transforming perceptions of nature. It mixes simulation with reality, entertainment with education, and consumption with conservation. It makes of nature an exuberant and wholly artificial spectacle, even as it aspires to inform customers about actual imperiled ecosystems. The Rainforest Café uses animals for amusement and hopes to protect endangered species. It tempts us to eat and buy and asks us to reduce and recycle. It’s imaginative and it’s fun, and it’s now the best place to experience our confusion about nature and to begin to understand what we ought to do about it.

The first Rainforest Café opened at the Mall of America in 1994; today there are twenty-five (and counting) in the United States and ten overseas. The brainchild of Steven Schussler, an entrepreneur with experience in advertising and restaurants, the concept was developed over some seventeen years. For a while, it existed as a prototype inside Schussler’s home in St. Louis Park, Minnesota. Schussler had parrots, toucans, tortoises, an iguana, and a diaper-clad baboon; he claims that it was his wish to give these pets a cageless environment that inspired the Rainforest Café. “It became my passion to educate and entertain people about the rain forests, which are the lungs of the world,” he said. The café—which combines, says Schussler, “the sophistication of a Warner Bros. store with the animation of Disney and the live animals of a Ringling Brothers/Barnum and Bailey circus”5—has proved wildly successful, both popular and remunerative.

In all its diverse locations, the Rainforest Café is much the same, a large shopping and dining space decorated and lit to simulate a fabulous and exotic jungle. The Café at Disney Village is perhaps the most elaborate to date. It is housed in a sixty-five-foot-tall artificial mountain that steams and thunders at regular intervals. Water cascades down the outside, past real and fake plants. Audio-animatronic animals, from butterflies to iguanas to giraffes, beckon to passers-by. The cavernous interior is divided into retail and eating areas by a huge, arched, saltwater tank containing simulated coral and real tropical fish. The bar is constructed to look like a gigantic toadstool. Walls are fashioned of faux rock; artificial plants, vines, and Spanish moss are draped from every nook and cranny. Water spills down the walls and mists out from fountains. Fans pumps into the air a “rain forest aroma” created by Aveda Corporation from floral extracts. Simulated tropical storms convulse the place every twenty-two minutes, complete with flashes of lightening and booms of thunder. More audio-animatrons perform: elephants trumpet and gorillas beat their chests. Meanwhile, real macaws and cockatoos are on display for consumers’ amusement and edification.

In the end, the Rainforest Café is more jumble than jungle. While purporting to depict the tropical rain forest, it creates a hodgepodge of different ecosystems, from ocean reef to savannah. Stirred into the mix are such non-rainforest animals as zebras, giraffes, and elephants. The melange of environments makes the Rainforest Café seem less like a simulation than like what Jean Baudrillard describes as a simulacrum: a copy for which no precedent exists.6 As if that weren’t confusing enough, the place features a talking banyan tree named Tracy, who delivers the ultimate mindbender: at intervals she mouths exhortations to “reduce, reuse, and recycle,” while at other intervals she urges us to try the tasty food or buy the themed merchandise. Conserve, conserve, conserve. Consume, consume, consume. More and more, as the Rainforest Café makes acutely clear, conservation and consumption are two sides of the same cultural currency.

But this simulated cloud has a silver lining. Each Rainforest Café features an animatronic crocodile in a pool into which customers throw coins. The money is collected and donated to groups who work to preserve the rain forest, including the Rainforest Alliance, the Center for Ecosystem Survival, the Rainforest Action Network, and the World Wildlife Fund. Simulated rather than real coral is used in the fish tanks so as not to contribute to the destruction of living reefs. Only line-caught fish are served, and the kitchen tries to avoid buying beef from deforested areas. In 1999, the company became the first national restaurant chain to serve what it calls “bird friendly” shade-grown organic coffee—coffee which does not require the extensive clearing of trees since it can be grown under the existing canopy. Live animals at the Rainforest Cafés are carefully tended: each café has a full-time curator (some with degrees in ornithology or marine biology) and a trained staff to care for the fish and birds. The birds come not from the wild but from selected domestic breeding programs. And in 1997, the corporation reportedly spent $175,000 per unit on outreach programs, for instance, taking the parrots to schools and “educating children about the plight of the rain forest.”7

But none of this conspicuous do-gooding disguises the fact that both the ecological and educational messages at the Rainforest Café are garbled. We can, so the message goes, have it both ways—we can consume and conserve at the same time. This is illogical, to say the least, and possibly deceptive, in that it might comfort some into thinking that consumption and waste aren’t among our most pressing social and environmental challenges. As at the Nature Company and the Body Shop, the Rainforest Café tries to entertain us, to make us feel good in its approximation of nature; but it does not teach us to be responsible. (In fairness, its promotional material claims only that the chain is “environmentally conscious,” not environmentally responsible.) We do not learn about the remote consequences of our consumption—what resources were used, what environments might have been disrupted, what exploited labor might have been employed, where our waste will end up. Under the guise of education and conservation, the Rainforest Café sustains the overconsumption of resources that characterizes middle- and upper-class American life. At the same time, it offers a lesson in the commercial re-creation of nature; as a simulacrum, it exemplifies a new phenomenon in which nature is neither represented nor copied, but replaced by a wholly human concoction.

Malls are only one part of the commercial landscape; the same redefinition of nature is happening at theme parks. Sea World, for example, has recently opened the five-acre Key West World, just 350 miles from the real Key West. It is a miniaturized, sanitized version of the southernmost U.S. city, complete with pastel-shaded knockoffs of local architecture, non-alcoholic margaritas, and performers impersonating colorful characters of Key West, including a sand sculptor (“she’s interactive,” we are told) and a magician pretending to be W.C. Fields selling swampland. Key West World includes interactive animal exhibits: a stingray lagoon, where kids can feed shrimp to the rays, and an artificial reef with dolphins to feed and pet. The reef features plastic sea fans and fiberglass-reinforced concrete coral; it is gently washed by mechanical waves, which roll back to reveal plastic shells in rocky grottoes. Fake rocks are better than real ones, Sea World’s curator told a Washington Post reporter, because “real rock doesn’t have as much character as the molds.”8

Sea World is more famous for a show featuring Shamu, the copyrighted killer whale, which combines real-time animal action with a large-screen video documenting the lives of orcas in their natural habitat. The real and the reproduced play simultaneously here, accompanied by a voice-over that allows Sea World’s parent company, Anheuser-Busch, to boast that they are being good corporate citizens, researching and protecting endangered species—although they never explain precisely how. They want you just to have fun and relax—multinational capital is minding the environment. From the show itself, however, you would never know that they had learned anything about whales. The exhibit features whale behavior as a form of acrobatics without explaining its function in the wild. One of the most spectacular moments of the show, for example, occurs when the whales launch themselves out of the water and slide at great speed across a platform. What you are not told is that this is a predatory behavior whose purpose is to capture seals. Presumably the message of one lovable sea creature consuming another is deemed too “negative” for the entertainment industry.

I have mixed feelings about nature as presented in places like Sea World. To the extent that the Sea World experience imparts information, I applaud it. But the balance generally tips toward a lowest-common-denominator kind of entertainment, as in a “ride” called Polar Expedition, which involves taking a seat for a simulated flight, shaking around a lot, and pretending to land somewhere in the Arctic. Leaving the flight simulator, you enter a dark, icy landscape at a supposed polar research station, with tanks containing walrus, narwhal, and polar bears. Underlying Polar Expedition in particular and the Sea World experience in general seems to be the assumption that the animals are not sufficiently compelling on their own, that some feeble narrative—or some copyrighted name—has to be fashioned to make them amusing.

Like UnderWater World, Sea World is, finally, neither very entertaining nor very educational. Both represent the burgeoning “infotainment” industry, which attempts to combine the features of an amusement park with the educational mission of the nonprofit zoo, aquarium, or natural history museum. But the bottom line is that these are for-profit entities, and education will always take second place to money. A detailed presentation of wildlife ecology and a reasoned discussion of environmental problems doesn’t sell like the thrill of a pseudo-adventure. Just ask Disney: after painstakingly replicating the botany and zoology of the African savannah at Animal Kingdom, they drag you across the place in pursuit of some fictional poacher.

More complex is the issue of touching and feeding wild animals, as is permitted with dolphins at Key West World. Allowing people to develop psychological bonds with animals perhaps encourages an emotional commitment to the preservation of other species. Meeting animals on a middle ground somewhere between a civilized and a wild place might even be beneficial to the preservation of native habitats. The kinds of simulations encountered in places like Sea World might even be demographically inevitable. As the global population grows and as ecosystems become more fragmented and imperiled, perhaps the best we can do is to leave these places alone. If we can satisfy our urge to experience fragile ecosystems by visiting a simulation, we do less damage to the real thing. On the other hand, if we can manufacture a really convincing and entertaining fake, who will care about the original? Let the real coral reefs die—they will live on as a simulation, courtesy of Anheuser-Busch or Rainforest Café.

One more problem must be raised: whether for consumption, education, or entertainment, commodified nature is only for the affluent. Entrance to Sea World costs $39.95; neither food nor merchandise at the Rainforest Café is inexpensive. The poor have a different relationship to landscape, one governed by scarcity and recycling. Salvage, not consumption, is a conspicuous feature of low-income culture. Infotainment landscapes are another index of the large and growing distance between the haves and have-nots. We may well be witnessing the emergence of three classes of landscape experience: the affluent will make their eco-tours to the remaining fragments of pristine habitat; the middle classes will visit simulations; everyone else will inhabit marginal landscapes, salvaging and recycling to survive.

I will conclude with two questions. Should we resist the commodification of nature in the commercial environment? And if so, how? It will be apparent by now that I think we should, for many reasons. The commercial landscape is implicated in some of the most unsettling trends in contemporary culture: the growing gulf between rich and poor, and hardening patterns of social and economic segregation; the tendency to identify people as target groups of consumers rather than as citizens; the transfer of economic resources from the city to the suburb; and the privatization of communal space and the corresponding devaluation of urban public areas as the locus of civic life. The commercial landscape dishes up an ever-changing menu of amusing diversions that hides the real terms of our relationship to the global environment. In the theme park and the local mall, consumption has no consequences. The commercial landscape promotes the misleading notions that we can conserve and consume at once and that our transactions with nature can invariably be safe, agreeable, and problem-free.

Maybe I’m hopelessly reactionary, out of touch with cultural imperatives. Maybe the simulated, commodified nature sold to us in the mall and the theme park is the nature we want. Perhaps we’d rather live in the realm of reproductions, inhabiting a simulacrum of nature instead of what I still want to call the real world. Perhaps the commitment to biodiversity and to the cultivation of healthy, unpredictable, dynamic, and (dare I say?) beautiful landscapes is merely nostalgic, rendered obsolete as we remake nature entirely in our own image. Simulated nature is certainly a lot less complex and troublesome than the real thing, and our appetite for it now appears boundless. The sheer popularity of simulations demands that we acknowledge, even respect, their cultural importance. Yet I wonder: are we, as consumers, being given what we really want in these commercial landscapes, or are we being sold a bill of phony goods? Commodity producers don’t just make products; they manufacture the desire for them. Consumers are never completely passive, but nor are they (we) immune to the seductive powers of marketing. In the absence of now-constant advertising, perhaps consumers would not be as attached to commodified nature as its producers would like to believe.

It is hard to know how to resist. Only the eco-warriors will opt out completely; the rest of us are unlikely to want to make do with much less than we currently consume. Yet I’d like to imagine the emergence of a populist environmental politics, a broad-based challenge to the culture of consumption. A certain amount of organized consumer resistance might inspire commodity producers to reformulate their representations of nature, helping us to imagine, as environmental historian William Cronon puts it, “what an ethical, sustainable, honorable human place in nature might actually look like.”9 I’d also like to imagine enlightened action on the part of corporations that inhabit the spaces of malls and theme parks. A few are beginning to recognize the economic and public relations benefits of increased recycling and diminished resource consumption, but changes in patterns of production and consumption have been few and largely symbolic. We’re a long way from leasing such things as appliances, automobiles, and home furnishings and returning them for recycling when we are finished with them, instead of consigning them to the trash heap.

Whether change comes from producers or consumers, we need to make room in the spaces of the theme park and the shopping mall for some alternative narratives and for some dissent from the ideology of consumption. We need to integrate better our natural and social economies; that is, we need to be able to see the connections between the landscapes of production and consumption—to understand the environmental and human costs of waste. We need to hold out for healthy ecosystems in the city and the suburbs; we need to insist that culture—however much it might flirt with simulation—retain a focus on the real world, its genuine problems and possibilities. At the mall or the theme park, what does this mean? Can we imagine a mall that is also a working landscape—that is energy self-sufficient, that treats its own wastewater, and that recycles its own materials? Can we imagine a theme park that is genuinely fun and truly educational and environmentally responsible all at once? I don’t see why not. We have created the “nature” we buy and sell in the marketplace; we should certainly be able to change it.

John Beardsley is a writer and curator who teaches at the Harvard Design School; his books include Earthworks and Beyond: Contemporary Art in the Landscape.