Beautiful Big Feet

For almost 1,000 years, young Chinese girls were forced to bind their feet so they could marry citified elites, since their natural “big” feet were associated with provincial people and rustic life. At first, foot-binding was the sole privilege of the high class. The practice flourished until the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. Respected intellectuals had written poems and created paintings to praise artificial tiny feet that today would be considered grotesque and abused. Painters portrayed classic Chinese beauties with small feet, flat breasts, tiny waists, and white skin, in complete contrast to strong and healthy peasant girls. For a long time, in other words, the beautiful has been seen as necessarily unproductive, above the “crude,” survival-oriented processes of nature.

Little Feet/Big Feet: Sustainability and Aesthetics in China

This definition of beauty and its connection with high-status urbanites is not unique to Chinese culture. Pre-Hispanic Mayan priests and nobles deformed their children’s bodies in a quest for social status. Their “beautiful” features—sloping foreheads, almond-shaped eyes, large noses, and drooping lower lips—today seem as grotesque as bound feet.1

For thousands of years, the urban elite worldwide has maintained the right to define beauty and good taste as part of its assertion of superiority and power. Bound feet and deformed heads are among the thousands of cultural practices that, in trying to elevate city sophisticates above rural bumpkins, have rejected nature’s inherent goals of health, survival, and productivity.

Pearl S. Buck vividly depicted this process of urbanizing and denaturalizing taste in her novel about Chinese village life, The Good Earth (1931). Early on we meet Wang Lung, a poor man who could marry only a slave from the local aristocrat’s Great House. The slave was very productive, giving birth to three sons and two daughters. She was not beautiful, but she was hardworking, cooked and kept house well, and begged in the streets to relieve her family’s poverty. Wang Lung eventually became so wealthy that he didn’t need to labor himself but instead hired farmers. He could even afford to leave his land unfruitful, buy from others, and build rooms to accommodate a slender beautiful woman as his concubine, who was prevented from working or having children. As Wang Lung’s property increased, he was able to rent the Great House as his family’s residence and live in town. His unproductivity was the measure of his social “success.”

Mixed into in the evolution of the Chinese idea of beauty are people’s changing ideas of urbanity and good taste in landscape design. For thousands of years, farmers had managed living landscapes using the survival skills passed on by their ancestors through endless trial and error. Generations had adapted to both the threat and the results of natural disasters—floods, droughts, earthquakes, landslides, and soil erosion—while honing their abilities in field grading, irrigation, and food production. A popular story arose: Our ancestors created and maintained “The Land of Peach Blossoms,” a lost paradise, a productive and harmonious basin discovered by a fisherman.2 Efforts to survive were what engendered the skills and artistry of rendering the landscape productive and durable. People found this land beautiful because it had the order and integration with natural processes that resulted from working with the given.

But as China has become more urbanized and “civilized,” this vernacular landscape has gradually been deprived of its productivity, its support to and of life, and its natural beauty. Like the peasant girls whose footbinding crippled them, it has gradually been adapted by the minority urban upper class and transformed into artificial decorative gardens. The aesthetic of uselessness, leisure, and adornment has taken over as part of a larger overwhelming urge to appear “modern” and sophisticated.

But designed landscapes and gardens in different cultures have roots in the agricultural landscapes that were the first expressions of civilization: Islamic gardens evolved from dry fields that needed irrigation. Italian terraced gardens originated as vineyards adapting to steep slopes. Picturesque English landscapes began as pastures. And Chinese gardens have roots in agricultural farms. But the owners and designers of urban gardens didn’t appreciate the vernacular peasant landscapes, which were associated with the disheveled working class.

Using ornamental plants and artificial rocks for 2,000 years, emperors and nobles created a fake Land of Peach Blossoms for the pursuit of indolent pleasures. Irrigation ditches and ponds were turned into ornamental water features. Fish farms were stocked with mutant ornamental goldfish. Green plants were replaced with golden- or yellow-leafed ones; vegetables and herbs were ousted by ostentatious peonies and roses. Healthy trees were pruned, twisted, dwarfed, and damaged to make bonsai. Only “delicate” Small-Foot rocks were arrayed. Peach trees unable to bear fruit were planted. Like tiny-footed women, these urbane ornaments produced little and survived only with constant human upkeep. They were watered, pruned, weeded, and artificially reproduced. Most of the “great gardens” in history decayed soon after their owners passed on. What survives or has been revived today requires endless maintenance.

Please don’t misunderstand me: In one sense all art, music, and dance is “unproductive”—it is useless for sustaining biological life. I am not arguing for the end of all this or for any demeaning of the value of beauty and pleasure in our lives. What I am arguing is that in our resource-depleted and ecologically damaged and threatened era, the built environment must and will adapt a new aesthetic grounded in appreciation of the beauty of productive, ecology-supporting things. Our desire for beauty detached from utility is weakening, and it should be. In our new world, survival is at stake. Wastefulness becomes viscerally unattractive, if not immoral. But there is plenty of opportunity for joyful pleasure in useful things.

From Rusticitas to Urbanitas and the Challenge of Survival

The massive movement of people from rural to urban areas is a recent phenomenon. Today more people are living in cities than in the countryside. In the past century, the proportion of urban population worldwide rose from 13% in 1900, to 29.1% in 1950, to 48.6% in 2005; it is expected to rise to 60% (4.9 billion) by 2030. By 2050 over 6 billion people, two-thirds of humanity, will be living in towns and cities.3

For 2,000 years prior to 1950, China’s urbanization was enabled by agriculture surpluses, and its urbanization rate barely reached 10% (13% in 1950). By the end of 2007, around 43% of the 1.3 billion Chinese were urbanites. Each year some 18 million people migrate to China’s cities. The UN has forecast an even number of urban and rural people in China by 2015.4

The aestheticized landscapes defined by the privileged urban minority prior to the 20th century are now eagerly sought by the mass population, whose peasant ancestors had struggled for generations to become city dwellers. These migrants, just like the peasant Big-Foot girls, are eager to bind their feet, to gentrify themselves physically and mentally. Contemporary Chinese landscape, architecture, and urban design simply reflect the aspirations of ordinary people to become sophisticates.

Before the recent swarming to cities, ornamental landscape and civic design in China projected the aspirational identity of the privileged urban class typically through European Baroque landscape designs and ornamental gardening. These elite spaces have now turned into newly developed urban settlements and public spaces. Post-vernacular inherited values about urbanity changed not only the city but also the whole landscape of China. Rough and wild rivers are channelized and lined with marble. Rustic wetlands are replaced with fountains and immaculate artificial ponds. “Messy” native shrubs are uprooted and replaced by exotic horti-cultural ornaments; native grasses are replaced by tidy exotic lawns that consume more than one cubic meter of water per square meter each year in Beijing and in most of China.

From 2002 to 2010, China will have consumed about half of the world’s total production of cement and more than 30% of its total production of steel.5 Is this necessary to urbanize a rural country? Not completely, since some of these non-renewable resources are being wasted in the destruction and controlling of “messy” nature and the creation of ornamental landscapes and visually “iconic” buildings. Examples include the new Olympic Park, the steel-wasteful Bird’s Nest Olympic stadium, the exorbitant and “spectacular” CCTV Tower, and the energy-gorging National Centre for the Performing Arts. The beautiful Bird’s Nest consumed 42,000 metric tons of steel (roughly 500 kilograms per square meter). The CCTV Tower consumed nearly 300 kilograms per square meter and is the most expensive building in the world in terms of steel used.6 Millions of dollars were spent on decorative flowerbeds during the 2008 Olympic Games: Between 40 to 100 million flowerpots were used.7 Imagine how much better Beijing’s air pollution would be had those been forty million trees. In Shanghai almost all landmark buildings are crowned with ornamental hats: One hat represents a lotus flower, another a lily, another a screwdriver, a fourth a UFO. The city is trivialized by this frippery.

In the current Chinese “City Beautiful Movement” (or rather “City Cosmetic Movement”), the arts of urban design, landscape, and architecture, guided by the Small-Foot aesthetic, have lost their way in a search of mind-numbing conventional styles or meaninglessly wild forms and exotic grandeur. Work in these modes accelerates the degradation of the environment. China has 21% of the world’s population but only 7% of its land and fresh water. Two-thirds of its 662 cities lack sufficient water; 75% of its rivers and lakes are polluted. In the north, desertification has created a crisis. In the past fifty years, 50% of China’s wetlands have disappeared. The ground water level drops one meter each year in many sites.8 These conditions and trends are desperately unsustainable. What values do we hold as designers? Both global and local conditions compel us to embrace an art enmeshed with fostering survival, promoting land and species stewardship, and making ornament subservient to those goals. We need a new aesthetics of big feet—beautiful big feet.

The Big-Foot Aesthetic: Recovering Landscape Architecture as the Art of Survival

As people worldwide have finally admitted, anthropogenic climate change has brought and will bring additional floods, storms, droughts, diseases, extinction of much animal and plant life, and other threats to survival. A new study shows that CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel burning and industrial processes are increasing three times faster than speeds in earlier predictions: The Arctic ice cap is melting three times faster; the seas are rising twice as rapidly.9 On every continent some rivers are drying out, threatening severe water shortages.10 We are experiencing the greatest wave of extinctions since the disappearance of the dinosaurs: Every hour, three species disappear.11 To quote Albert Einstein, it is obvious that “we shall require a substantially new manner of thinking if mankind is to survive.”12 This will entail a shift in what seems pleasurable and beautiful to us, especially in landscape architecture, a crucial profession in the struggle for sustainable ecology.

Make Friends with Floods: The Floating Gardens of Yongning River Park, Taizhou

This project demonstrates how we can live and design with nature, enacts an ecological approach to flood control and storm-water management, educates people about solutions to flood control other than engineering, and reveals the beauty of native vegetation and the ordinary landscape.

The site occupies 21 hectares (52 acres) along the Yongning River, the mother river of the historical city of Huangyan on the east coast. Most of the site was already embanked with concrete as the result of the local flood control policy and before a landscape architect was asked to “beautify” it. Our firm successfully convinced the local decision-maker to stop the conventional flood control engineering along the remaining part of the river and to create instead an ecological flood control and stormwater management system.

A water process analysis dictated a regional drainage approach; concrete embankments were removed and replaced with wetlands that provided flood mitigation, biodiversity conservation, outdoor recreation, environmental education, and local historical and cultural demonstrations. Native grasses—“ugly weeds” most thought—were used to stabilize the riverbanks. On the recovered natural landscape is a network of straight paths and informational mounted texts to help people enjoy the natural processes and learn about local history. The results have been remarkable: Flood problems were successfully addressed; frogs, fish, and birds have returned; local television celebrated the “weed” grass in blossom on prime time; and hundreds of thousands of people visit to appreciate what would have been considered a messy and uncouth landscape.13

Revalue Common Culture and the Beauty of Weeds: _Zhongshan Shipyard Park_

This park covers eleven hectares (twenty-seven acres) in Zhongshan in Guangdong Province. It is built on the site of an abandoned shipyard that was originally constructed in the 1950s and went bankrupt in 1999, seemingly insignificant in Chinese history, and therefore likely to be razed to give space for urban development and a grand “Baroque” garden. But the shipyard reflected the remarkable fifty-year history of socialist China, including the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, and recorded the experiences of common people.

The principle of reducing, reusing, and recycling natural and man-made materials is followed. Original vegetation and natural habitats were preserved, just as only native plants were used throughout. Machines, docks, and other industrial structures were recycled for educational, aesthetic, and functional purposes. The design addresses several challenges of the site, including accommodating variable water levels and balancing river-width regulations for flood control with protecting old riverbank banyan trees.

Completely different from the classical Chinese scholar’s gardens, this park, since its inauguration in 2002, has become an attraction to tourists and local residents. It has been used all day and yearlong, has become a favored site for wedding photographs, and has even been used for a fashion show. It demonstrates how landscape architects can create environmentally friendly public places full of cultural and historical meaning but not on sites previously singled out for attention and preservation. It supports the common people and the environmental ethic “Weeds are beautiful.”

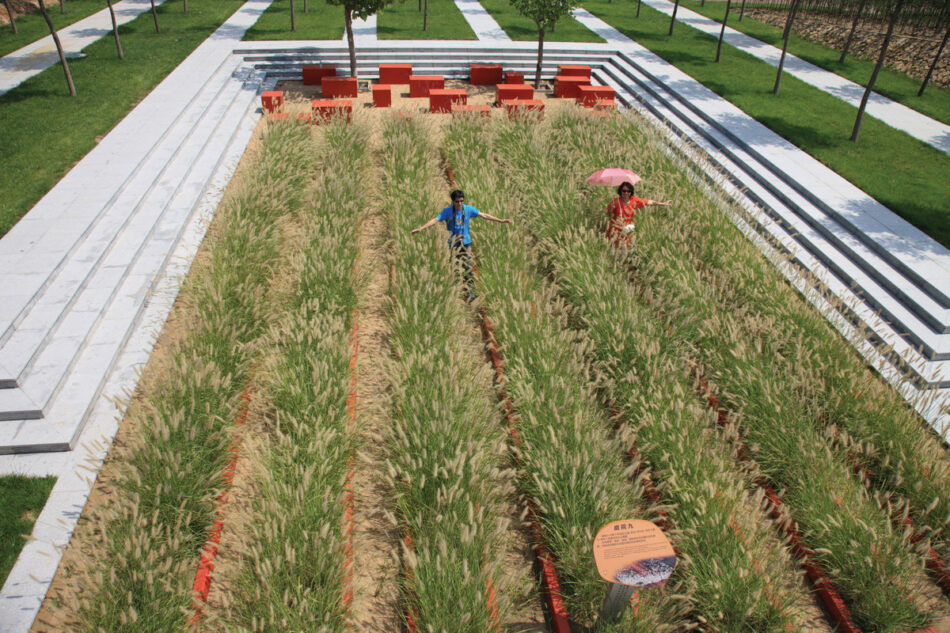

The Productive Landscape: _The Rice Campus_ of Shengyang Architectural University

This project demonstrates how agricultural landscape can become part of the urbanized environment and how cultural identity can be created through an ordinary productive landscape. The overwhelming urbanization of China is encroaching upon much arable land. With a population of over 1.3 billion people and limited tillable land, food production and sustainable land use is a survival issue that landscape architects must address.14

The site of about 80 hectares (198 acres) forms the new campus of Shengyang Architectural University. The design and construction had to contend with a small budget and a short construction timeline (six months), but the university still wanted the landscape to provide a strong identity. My firm proposed creating productive rice fields (along with other native crops) while fulfilling the need for new functions. Storm water is collected in ponds to irrigate the fields. Frogs are raised to control insects, and fish are cultivated to double the productivity of the field. Sheep “cut” the grass, eliminating the pollution of mowing machines.

Student involvement is part of the landscape’s productivity. Each year a planting festival and a harvesting festival are held on campus, which bring Chinese culture alive. Farming processes become an attraction to the students of the university and the nearby middle school. The crop is packaged as “Golden Rice,” which is sold in the university canteen and presented as souvenirs to visitors. Now Golden Rice has become the university’s identity marker, well-known across universities nationwide.

The Rice Campus increases sensitivity about the environment and farming among the mostly urban students. It demonstrates that inexpensive and productive agricultural landscapes can also become, through careful design and management, pleasurable social spaces. And finally this working landscape is a clear example of the new Big-Foot aesthetic—unbound but beautiful.

Minimum Intervention, The Red Ribbon: _Tanghe River Park_, Qinhuangdao

In natural terrain and vegetation, the landscape architect placed a 500-meter “red ribbon” integrating lighting, seating, environmental interpretation, and way-finding. While preserving as much of the natural river corridor as possible, this project demonstrates how a minimal design solution can achieve dramatic improvements.15

The site was in good ecological condition: Lush and diverse native vegetation provided habitats for many species. Located at the edge of the Tanghe River, which runs through the Qinhuangdao, it was, however, unkempt and empty, used for garbage dumping, and spotted with deserted shanties as well as irrigation ditches and water towers built years ago. Filled with scruffy shrubs and “messy” grasses, the site was inaccessible and unsafe. The government wanted to use it not only for urban sprawl but also for fishing, swimming, and jogging.

The lower reaches of the river had already been channeled with marble and “beautified” with ornamental plants, and channeling was likely to be carried out at the site. To prevent this, our firm proposed the red ribbon design. After the rehabilitation of the littered and polluted areas, the insertion of the ribbon was a light intervention. The ribbon brightens this densely vegetated site, links diverse natural vegetation types, and provides a structural means of reorganizing the formerly unkempt and inaccessible site. The park is urban and modernized—attributes highly sought by the local residents—while enhancing the ecological processes and natural services of the site.

Let Nature Work: The Adaptation Palettes of _The Qiaoyuan Park_, Tianjin

This is a park of 22 hectares (54 acres) in the northern coastal city of Tianjin. Rapid urbanization had changed a peripheral shooting range into a garbage dump and drainage sink for urban storm water. The site was heavily polluted, littered, deserted, and surrounded by slums and rickety temporary structures that were torn down before the design was commissioned. The soil here is quite saline and alkaline.

The regional landscape is flat and was once rich in wetlands and salt marshes that have been mostly destroyed by decades of urban development. Though it is difficult to grow trees in the saline-alkali soil, the ground cover and wetland vegetation are rich and vary in response to subtle changes in the water table and PH values.

The overall design goal was to create a park that can provide a diversity of nature’s services for the city and the surrounding residents, including containing and purifying urban storm water; improving the saline-alkali soil through natural processes; recovering the regional landscape’s low maintenance vegetation; providing opportunities for environmental education about native landscapes and natural systems, storm-water management, soil improvement, and landscape sustainability; and creating a cherished aesthetic experience.

The solution was called “the adaptation palettes,” a name inspired by the adaptive vegetation communities that dot the landscape. A simple landscape architecture strategy was devised, one that included digging twentyone pond cavities 10 to 40 meters in diameter and 1.1 to 5 meters in depth. Some cavities are below ground level, others above on mounds; some are water ponds, some are wetlands, and some are dry cavities. Diverse habitats were created, and natural processes of evolution and adaptation were initiated. Seeds of mixed plant species were sowed to start the vegetation, and other native species were allowed to grow wherever suitable. Through the seasons’ evolution, patches of unique vegetation established a correspondence to the individual wet or dry cavities. A few cavities vary their spatial relationship to the top of the high water table, with one variation in depth of only 10 centimeters. The patchiness of the landscape reflects the regional water- and alkaline-sensitive vegetation. Within each cavity is a wood platform that allows visitors to sit in the middle of the vegetation patches. Along the paths is an environmental interpretation system that gives descriptions of natural patterns, processes, and native species.

The park realizes its core goals. Storm water is retained in the water cavities, allowing diverse water-sensitive communities to evolve. Seasonal changes in plant species occur and integrate with the beauty of the native landscape, attracting thousands of visitors every day. In the first two months of its opening, October to November 2008, about 200,000 people visited; the ecology-driven Big-Foot aesthetic produces objects of desire.16

Utopian Proposal: Beijing as New Garden City

Today’s Chinese cities and architectures are unsustainable: Our monumental architecture, wide roads, endless parking lots, huge city squares, flowered landscapes, and engineering-oriented municipal networks will eventually be seen as ghastly mistakes.

Future cities will be “new garden cities,” emitting low or no net carbon, productive and conservation-minded. Rainwater will no longer be discharged from municipal pipes but will be retained in local ponds and supplement groundwater. Green spaces will be full of crops and fruit trees, instead of ornamental flowers and fruitless trees. Rice and broomcorn will ripen in the fields of communities and schools. In the harvest season, animals and humans will take pleasure together. Architectural surfaces will support photosynthesis. The roofs will be fish-raising ponds, with the functions of heat preservation, energy saving, and food production. Cellars will be great mushroom factories.

The CCTV Tower will become a complex system combined with agriculture, animal husbandry, and fishery. In the hole of the “underpants,” several wind turbines will generate electricity. The National Centre for the Performing Arts, easily transformable into a greenhouse, will grow various fruits; its basement will grow mushrooms. The Bird’s Nest can become a national vegetable market. Its great steel framework can be used to hang vessels holding a kale yard in the air. Tiananmen Square can be converted into a sunflower field. While producing oil, it will offer citizens the chance to enjoy the daily movement of the bright flower heads tracking the sun. Transportation tools will be high-speed railway trains, connecting compact pedestrian communities, where people can pick up public bicycles. Outmoded parking lots can be used to grow wheat and vegetables, or become fishponds that collect rainwater.

The new garden city is a mark not of utopia but of ecological civilization. It is an art of survival.