Picketing and Pruning

Irene Figueroa-Ortiz

You are one of the most prominent and influential leaders of the farmworkers labor movement in the United States. Your advocacy work has yielded substantial reform of farmworkers’ rights in California and across the nation, including the creation of landmark state and federal laws to protect these workers. Who were the farmers and laborers that originally inspired you to dedicate your life to fighting for their rights?

Dolores Huerta

They were just regular people—very strong people. Most were immigrants from Mexico and other countries like Guatemala and El Salvador. They came to the United States to create better lives for themselves and their children. They had hopes that by being here and working hard their children would get a good education.

IFO

When, in 1962, you cofounded the United Farm Workers of America, one of the largest farmworkers’ labor unions in the United States, with Cesar Chavez and other activists, what were the specific social, economic, and workplace issues that you sought to improve?

DH

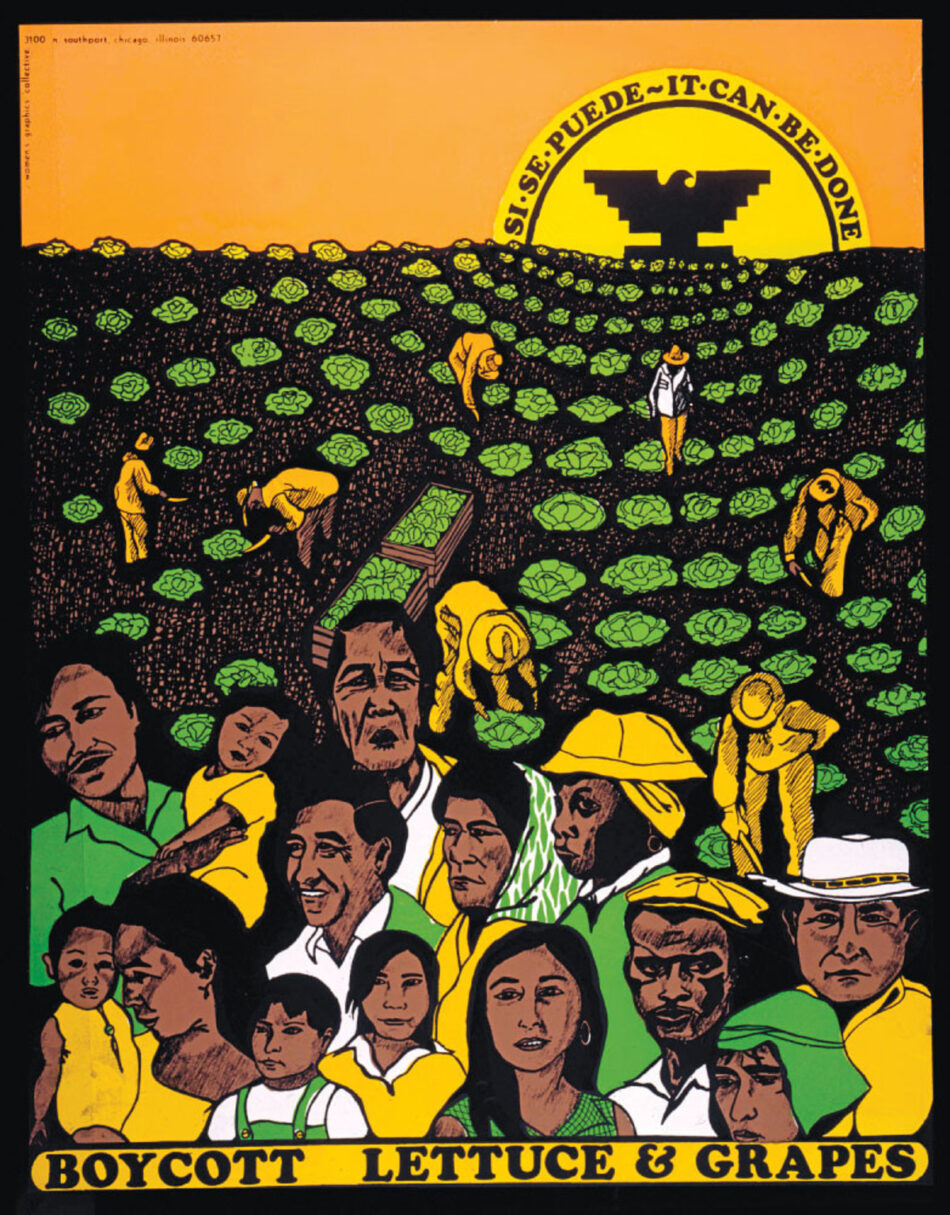

When we first started, farmworkers earned very little money—somewhere between 50 cents and 70 cents an hour. Employers did not provide them with toilets in the field, cold drinking water, or rest periods. They did not have access to unemployment insurance or the right to organize. Through our protests and boycotts, we were able to ensure that farmworkers across the nation could use restrooms, have access to cold drinking water, and have rest periods. Now, all workers in the United States are covered under the minimum-wage laws, even if they are undocumented.

But there is still a lot of room for improvement. Most states do not offer the protection that workers in California have, such as disability insurance or the right to negotiate contracts through labor unions. Only Hawaii and California have unemployment insurance for farmworkers. All of the benefits that workers enjoy today, like eight-hour workdays, weekends, social security, the minimum wage, unemployment insurance, disability insurance, pensions, and public education, were won by labor unions.

IFO

A fundamental topic in urban design and planning has been understanding and defining the relationships between various key services and land use. In rural settings, there are often disparities in access to education and health care as a result of geographic isolation and poor infrastructure. Are today’s migrant farmworkers and their families dealing with similar challenges?

DH

Because they live in rural areas, a lot of farmworkers do not have access to health care. Many are undocumented and therefore are not covered under the Affordable Care Act. The one thing that we do have is a very good national migrant education program; through it, lesson plans and studies can be forwarded to migrant children as they move from state to state with their parents.

Because most farmworkers do not have their own cars, there’s also a lot of exploitation in the realm of transportation. Informal, private van operators, who take workers to and from the fields, often charge around $10 a day.

IFO

Housing insecurity is another huge problem in rural communities. That’s why the federal government has dedicated funding to support the development of farmworker residences. However, these funding sources do not support the creation of multigenerational and mixed-income farmworker housing complexes. Federal grants tend to limit who gets access to these accommodations. Rather than yielding neighborhoods where people can age in place, these development grants are creating transient communities. What should be the role of housing delivery in supporting community-building among farmworkers?

DH

There are migrant labor camps, which are very useful for people coming in just for the season. Once it ends, people move on. In Bakersfield, California, we have a very nice facility that provides temporary housing for migrant farmworkers from May to October. But not all of the farmworkers are able to live in these camps; they are reserved mostly for families and are not accessible to single people. In California, they are trying to pass a law now that will allow single men to live in these facilities.

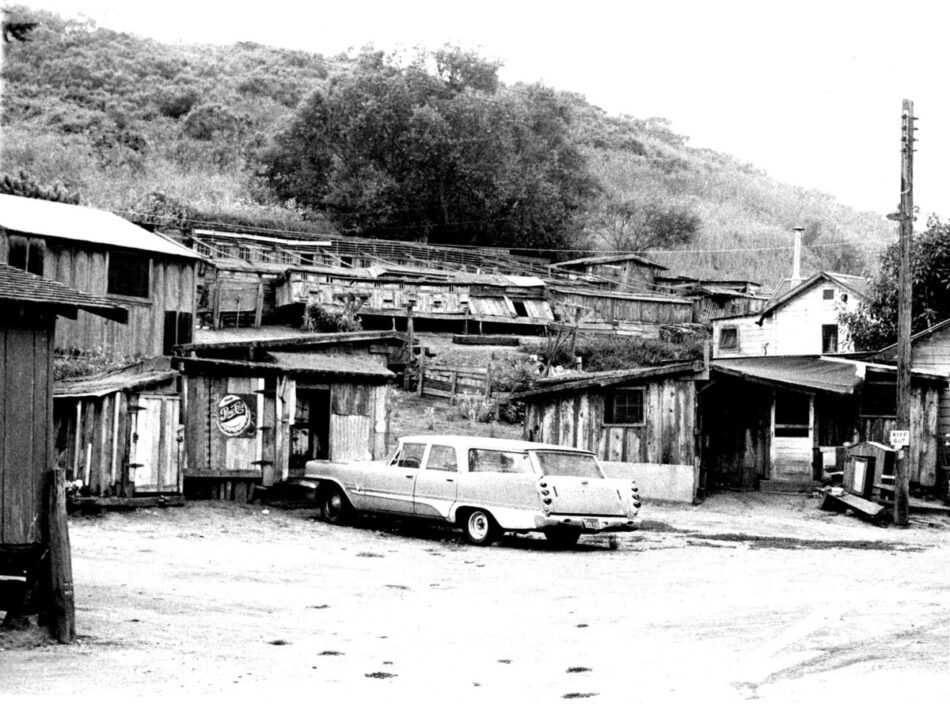

But there’s never enough housing. People coming in for the harvest are forced to live in really sordid conditions. The lack of low-income housing is a very big issue—not only for farmworkers, but for all low-income people. Rents keep rising; and when people cannot afford to pay the rent, they get evicted. There is a big housing crisis.

IFO

In contemporary architecture, designing housing that is accessible and flexible enough to accommodate different types of occupancy and lifestyles has also been a challenge. If I’m a person who cannot afford to rent a house, where do I go? If I’m homeless, does that mean that I have to camp in the fields or in my car?

DH

Exactly. Or they try to find families or relatives that can rent them a room. Sometimes there are 15 people living together in a single room—that’s very common during the harvest season. I remember going to visit a group of single men living in a little storage shed. It was not even a house. They literally could not sit down because there were so many of them in such a small space.

IFO

In your opinion, what are the ideal solutions for housing insecurity?

DH

We need more low-income housing developed by both the public and private sectors. The problem is that when people build housing they are thinking about profit, not about people’s needs. Our homelessness situation is evidence of that kind of philosophy.

IFO

This conversation brings me to another key issue in labor struggles: climate change. You were one of the first public figures to speak about environmental justice when you brought attention to the devastating effects of pesticides on farmworkers during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. In urban settings, we estimate that rising temperatures will exacerbate heat waves and, consequentially, that this will increase mortality rates due to overheating. What do you foresee the environmental and health impacts of climate change will be on rural farmworker communities?

DH

Climate change will not only affect farmworkers’ labor experience; it will also influence their economic condition and the terms of their employment because it will no longer be possible to grow certain crops. Farmworkers will die out there in the heat. There will be terrible consequences for other workers, too, like people who work in warehouses with no air conditioning. Once the temperature rises to a certain degree, a lot of people will be unable to work safely—but they will be forced to keep working. We have to make sure that people do not get heatstroke or die on the job site. This would mean altering the way the industry operates, including limiting the amount of time farmworkers spend in the fields. Farm owners are resisting these changes because one of the potential outcomes is that they would have to pay their employees at a higher rate so that they could still support themselves while working fewer hours.

IFO

How does the agricultural industry currently operate? What types of jobs did farmworkers perform in the 1960s, and how is it different from the work they do today?

DH

A lot of the work consists of picking and pruning. Today, a lot of that labor has become semi-mechanized. On a lettuce farm, for example, there are machines that go through the field and cut the lettuce. Then, the people pack it into boxes. But now they have to work very fast to keep up with the machines. In some ways, that kind of labor might be more stressful today than it was when the farmworkers were picking the lettuce themselves, at a slower pace.

IFO

Automation has slowly disrupted many industries and their job markets. How are these machines

impacting the agricultural industry and its demand for human labor?

DH

Machines are displacing an entire labor force. One cotton-picking machine, for example, can displace a crew of 40 workers. A farm owner might have only one machine and you would think, “Well, that one machine operator, he’s getting a decent pay.” Usually employers just pay the employees who manage these machines minimum wage and save a lot of money, because they no longer have to pay the salaries, or social security (or, in the case of California, unemployment insurance), of the 40 workers replaced by the machine. Employers are able to make a lot more money, but they do not pass on the extra profits to the consumer or to the farmworker communities.

IFO

If you cannot find a job in the field, where do you go?

DH

There is still a lot of work in the fields. While these machines are taking away some jobs, there are still many farmworker positions available. The number of fruits and vegetables that is being planted has taken up the workforce that would have been out of work otherwise. In California, there is solid work because as one crop ends another one starts. A farmworker here could work all year round in the fields, and, if for whatever reason they cannot, that person can just go up to Washington State to work on the hop, asparagus, or cherry farms.

IFO

Are there any other social and economic implications of having these machines in the fields, aside from the fact that it is more stressful for farmworkers’ everyday tasks?

DH

A lot of these machines are being developed at universities, like the University of California, Davis. The university is supported by taxpayers, so the machines are being created with taxpayer money. But then agricultural employers use that technology to displace workers. Farm owners get the technology for free, as it’s paid for by taxpayers, but they do not pass any of those savings on to the consumers or to the workers.

IFO

That makes me think of the subsidies the Trump administration is giving to farmworkers to offset the president’s trade war. Can you tell me a little bit more about that?

DH

The subsidies are not going to farmworkers. They are going to farm owners—the bosses. In California, there are huge business corporations that own thousands of acres, while a small farmer might have only a thousand acres. None of these subsidies are going to go to the workers—they are going to go to the employers, who are already wealthy.

IFO

So why are they getting subsidies then?

DH

Well, ask Donald Trump. [Laughter.] I mean, the answer is that he is getting so much criticism for the effects of his trade policies on farms, and this is his base, right?

IFO

This takes us to your current work: you went from being a dedicated farmworkers’ labor leader to a feminist political organizer. How did this change come to be, and how are these two lines of advocacy connected?

DH

I started out being a community organizer, and when I left the United Farm Workers of America I went back to being a community organizer. Our work at the Dolores Huerta Foundation, a nonprofit organization that I founded in 2002, focuses on organizing poor people—a lot of them farmworkers—so that they can have the power to improve their communities and fight against the issues affecting their lives.

We are facing all kinds of discrimination today, primarily aimed at people of color and women. Our work is about empowering people in their own communities, and of course we need to look at women! In every community where we organize, we encourage people to run for office, and we help them campaign so they can get elected. Early this year, we put pressure on the local county-voted supervisors to redraw the voting districts that were hindering representation of people of color on the Kern High School District Board of Trustees. Separate engagement is a very big part of the work that we do. Getting people civically engaged, voting, and serving on school boards, municipal water boards, and other planning commissions is very important.

Right now, we are focused on changing our educational system and making it more progressive so that it reflects the contributions of people of color, women, and the labor movement. In the process, we are trying to break down some of the discrimination and stereotypes that people face every day. Children need to be exposed at a very early age to the impacts of racism, sexism, and homophobia in our society. Another big focus of our work is stopping the school-to-prison pipeline by taking on school districts that are expelling and suspending our kids. Last year the Foundation reached a settlement in a lawsuit against the Kern High School District; now the schools in this district are required to provide cultural competency training for teachers and positive behavior intervention systems.

IFO

I would love to hear your thoughts on how architects, urban designers, and city planners could best support social and racial justice through their work.

DH

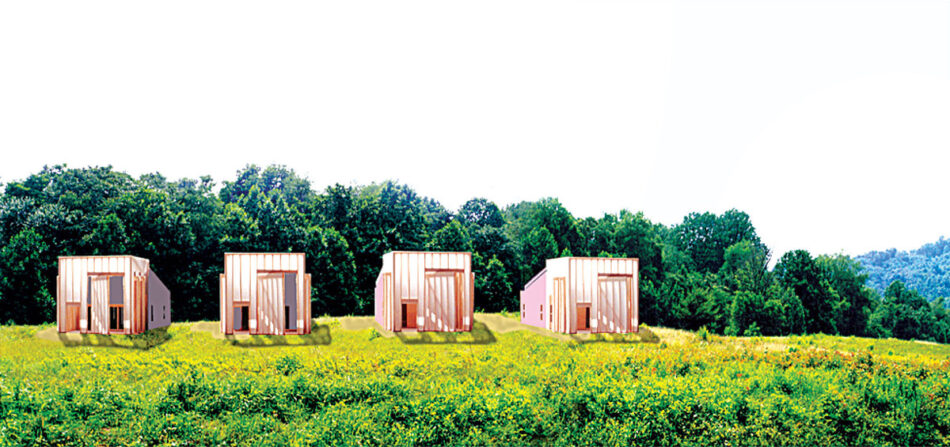

They can have a great impact. When planners are developing neighborhoods, they must design integrated communities so that poor people are not segregated to one part of the city. Low-income housing does not have to be ugly. Poor people shouldn’t have to live in ticky-tacky houses. All people should inhabit shelters that reflect their humanity. Architects should remember that people who work in the fields, in hotels, and in construction deserve to have decent, affordable, good, and beautiful housing.

Low-income housing is always the smallest percentage of new housing being built. We know that there is a need for affordable residences, and we should focus on building more. Not everybody needs a mansion to live in. Also, buildings should be environmentally friendly in their size and components. Planners have to think across the board, in terms of the whole world. Building housing should not be profit-driven.

IFO

In terms of organizing, is there any clear difference between organizing people in urban settings versus those in rural locations?

DH

No. To organize people you have to talk to people, to talk about the issues, to tell them how the issues can be solved. Whether they live in an urban community or a rural community makes little difference—it’s just about people coming together and people fighting for justice wherever they live. The one difference and difficulty is that in rural communities, because people do not live close together, you have to travel to get to people—and people have to travel to vote. But what it comes down to is just talking to people, informing them, motivating them, telling them how they can come together, how they can make changes. It just takes work.

Dolores Huerta is a civil rights activist and community organizer known for her dedication to labor rights and social justice for farmworkers. She is cofounder of the United Farm Workers union alongside Cesar Chavez and founder and president of the Dolores Huerta Foundation (DHF). The DHF connects groundbreaking community-based organizing to local, state, and national movements through registering and educating voters, advocating for education reform, bringing about infrastructure improvements in low-income communities, advocating for greater equality for the LGBTQ community, and creating strong leadership development. She has received numerous awards, including the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award from President Bill Clinton in 1998; in 2012, President Barack Obama bestowed Huerta with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the United States.

Irene Figueroa-Ortiz is an urban planner and designer whose work focuses on public realm design, planning, and policy. She is assistant planning director at A Better City, where she manages various public space initiatives in partnership with the City of Boston and the business community. She is an Enterprise Rose Architectural Fellow, a national initiative for public interest designers promoting inclusion and equity in community development.