Are Charrettes Old School?

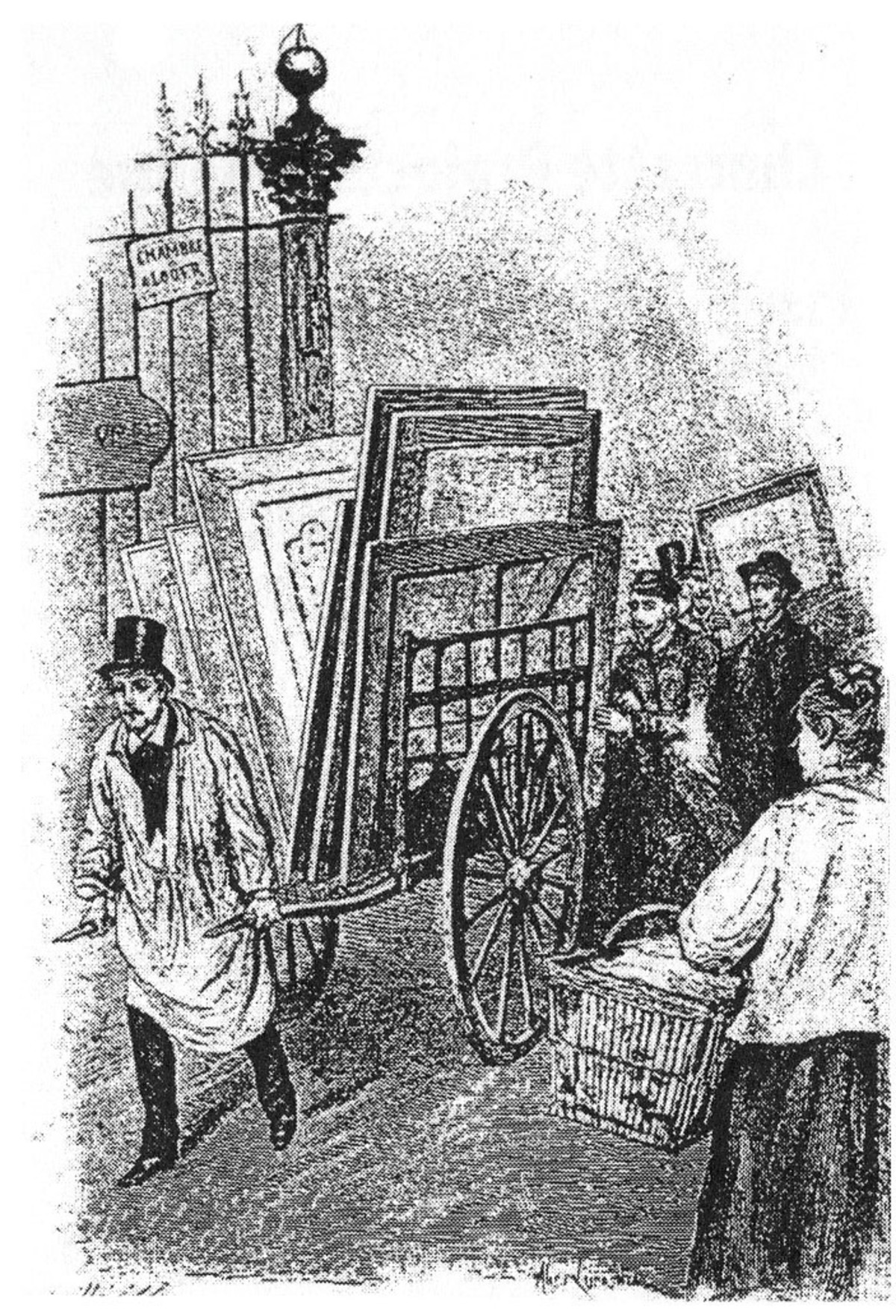

Does the charrette—the word comes from the French en charrette, with its image of École des Beaux-Arts students working on their drawings even as they were being taken away on a cart1—still exist in professional architecture offices? Is it an integral part of their culture, as it remains, stubbornly, in most architecture schools? My curiosity about these questions stems mostly from my awareness, as an educator, of the efforts by the American Institute of Architecture Students to eradicate the “all-nighter” from architectural education.2 Over the past few years, I’ve discussed the issues of work practices and time management with many professional architects, several of them alumni of the school where I teach. For this article, I asked these two questions to six architects representing a range of firm sizes and types. From largest to smallest, my sample included the multidisciplinary giant AECOM, with 45,000 employees worldwide; a very large firm, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, focused primarily on architecture; three medium-sized firms, O’Brien/Atkins, Bernardon Haber Holloway, and SMP Architects; and the small office of James Oleg Kruhly, a sole proprietor with typically no more than five employees.

Perhaps the most telling thing I found is that the definition of a charrette has changed. Most professional architects now equate charrettes with interactive brainstorming sessions. These kinder, gentler charrettes, held early in the design or programming stages of a project, place the client and other stakeholders, as well as all or most of the professional disciplines that will contribute to the project, in the same room for, usually, one to three days. Charrettes of this type, although they may be require sustained concentration, seldom demand the abandonment of family and friends or the compromises of personal health and hygiene that were the unavoidable consequences of the “old” charrettes.

The new collaborative charrettes are supported by facilitators and consultants and are endorsed by the U.S. Green Building Council and the National Charette Institute, which compiles best practices and issues guidelines for organizing them.3 They are also called “high perform ance” charrettes, due to their association with “high-performance buildings.”4 They are in step with our contemporary business climate, with its emphasis on teamwork and cross-disciplinary collaboration. Meanwhile the old charrette, according to Roger Duffy, a partner at the New York office of SOM, is “an anachronism,” an outdated “ritual of the profession” and of architectural education. In professional offices, “its time has passed.”5 And while these charrettes, which are nearly synonymous with the all-nighter, still exist in architecture schools, they are under attack not only by the AIAS but also by other advocates for student rights.6

The old charrette is the victim of forces beyond the control of the architecture profession. The 1972 consent decree between the AIA and the Department of Justice eliminated guaranteed fee schedules and, as a consequence, introduced competition between architects on the basis of fees.7 This change disturbed the détente between the dictates of business/profit-making and the emphasis on design that had previously existed within American architecture offices. The lack of competition on the basis of fees inculcated within mid-20th-century firms an acceptance of inefficiency and haphazard project management. It also allowed a “charrette ethos” to take hold, in part because working long hours allowed the firm to express that its commitment was foremost to design quality.8

Most architecture firms have now fallen into line with expected business practices for the compensation of employees. Movement in this direction was hastened by media attention—most notably Thomas Fisher’s 1994 Progressive Architecture article, “The Intern Trap: How the Profession Exploits its Young”—to the practices of unpaid overtime and unpaid internships. There are still architects whose practices rely on unpaid internships and whose work originates almost exclusively in competitions,9 but these are so few that they should probably be considered an alternative form (and subculture) of practice—one that cannot be easily reconciled with the evolving norms of most professional offices. To the extent that a charrette ethos still thrives outside the schools, it does so within this narrow subculture.10

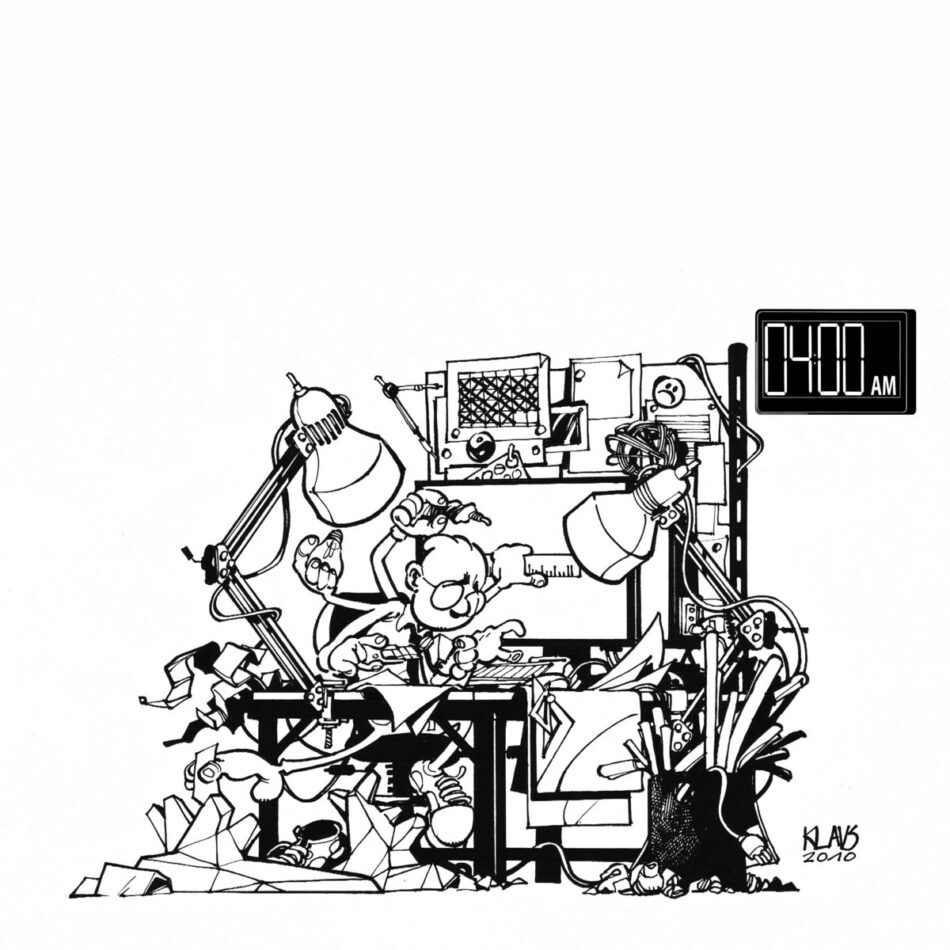

None of the firm leaders I spoke with considered architectural practice a forty-hour week, nine-to-five endeavor. All thought there was a natural “momentum” to a design project; times when you didn’t want to stop working for fear of losing inspiration. Jim Kruhly stated, “As momentum builds up, a convergence occurs. You have to take advantage of this. You can’t just go home for the week end.”11 All six firms offered some form of remuneration—from compensatory time to time and a half—to interns and other hourly employees for working additional hours. Obviously, such policies increase the impact charrettes would have on the profitability of firms and therefore serve as an incentive to limit them. It was not clear to me, however, that architects were working fewer hours than they used to. Like their similarly educated peers in other professions, midlevel architects, associates, and partners are working at least as much as their predecessors from twenty-five years ago,12 but the hours are spread evenly across the calendar, and much of the work is done while they are commuting or in the evenings and weekends away from the office.13 Bill Holloway, managing principal in the Delaware office of Bernardon Haber Holloway, confirmed my suspicion that, due to the increased emphasis on marketing and firm management, his “after-hours” work tends not to be directly related to design.14

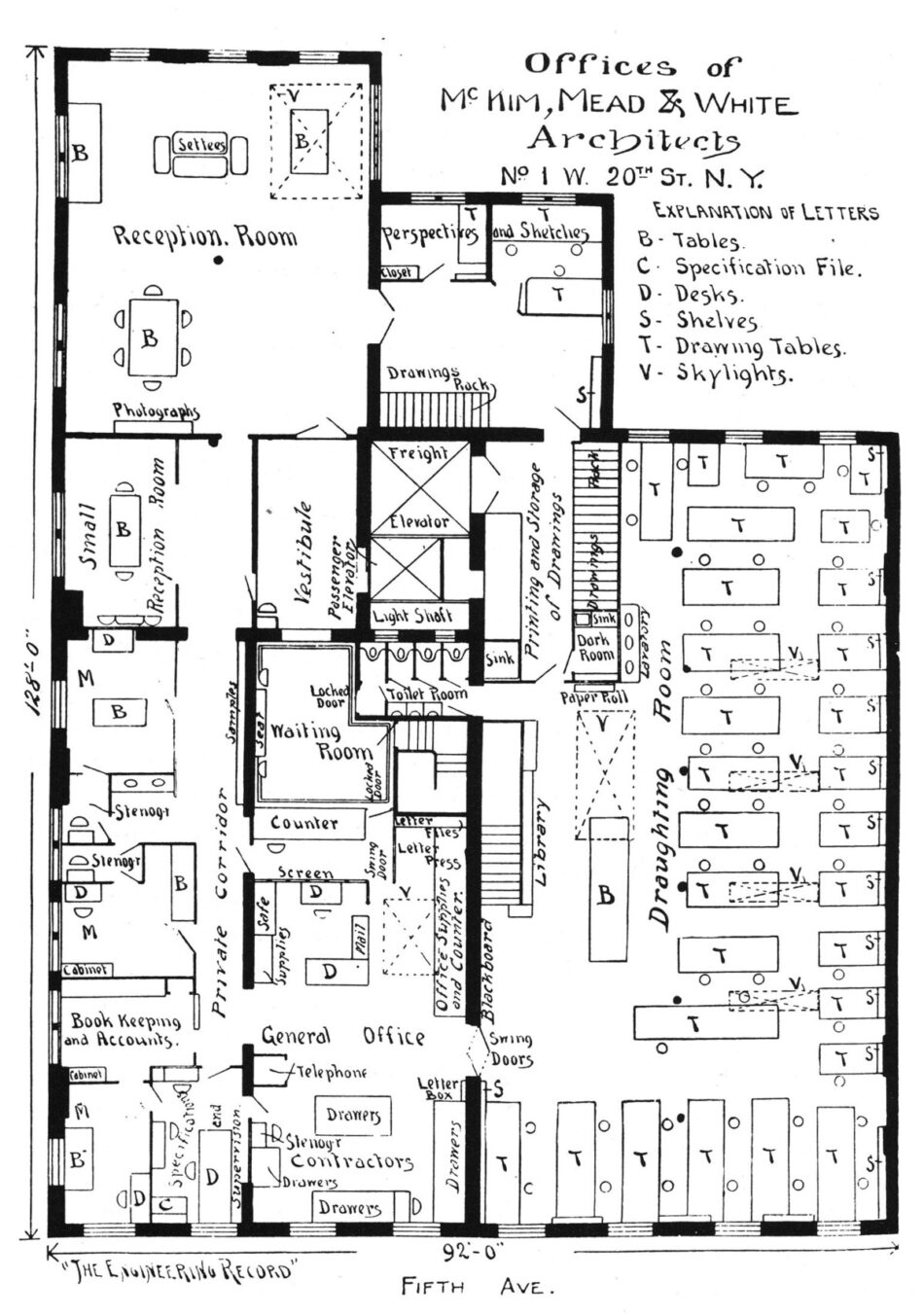

In the offices where I worked as a young architect in the 1980s, the imminence of deadlines for final construction documents always produced charrettes. None of the firm leaders when I interviewed for this article said that this was likely to happen today. As Ed Weaver, a vice president of AECOM, put it, if all-nighters are necessary to finish construction documents, that would “speak to a lack of competent management”—either the project itself was poorly managed, or the firm had made a blunder of another sort by agreeing to (or allowing the client to impose) an unrealistic project schedule.15

The other external influence that has led to the near extinction of the traditional charrette is new digital technology. Thanks to it, many of the most time-consuming aspects of practice can now be outsourced to specialists. The making of presentation-quality models is one task that is usually subcontracted, and paraprofessionals in the Far East can provide rendered perspective drawings more quickly and inexpensively than they can be produced in-house.16 For the offices that can afford them, digital tools such as 3-D printers and laser cutters are making the production of small massing and study models quite efficient. In this, architectural practice is following the lead of product design, incorporating “rapid prototyping” into its practices and professional vocabulary. Also being imported from engineering and product design are “performance-based” design methods that, whether or not they are truly superior to traditional trial-and-error methods, are more systematic and predictable. Additionally, digital technology has made collaboration across geographic distances more feasible. It is no longer essential to bring the design team together at one location in order to facilitate collaboration.17 And, of course, CAD has accelerated the production of construction documents, not only for architects but for all the disciplines contributing to projects.

Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) are also changing the time management in architecture offices. “Integrated practice” establishes, from the earliest stages of a project, the client, contractor, architect, and other consultants as part of a profit-sharing project team.18 In contrast to the traditional Design/Bid/Build method of project delivery, IPD involves the contractor(s) and construction manager during the design phase and removes the architect from her traditional privileged position as the primary link between owner and contractor. This reconceptualized relationship binds the architect to the work practices of others outside the profession. In fact, for large projects it is now rare that the architect will have any control of the project schedule. According to SOM’s Duffy: “Everything now is schedule based, and architects are not in charge of the schedule. The owner’s representative or construction manager controls the schedule. It is rare that we get a project in which we get to define the schedule.”

The architect’s traditional attitude toward the pace of design, which, with its recognition of the unpredictability of inspiration and its openness to improvisation, dis dained deadlines, is being replaced by precise time management. The presence of borrowed money in the typical building project overwhelms other concerns, leading to the greatest value being placed on predictability, risk avoidance, and minimum time until completion. Project schedules are now very sophisticated, specifying each week’s activities, meetings, milestones, and deliverables a year or more in advance. BIM also imposes a schedule discipline that favors steady production over the peaks and valleys once prevalent in architectural practice. In theory, all the varied consultants working with BIM should be developing their aspect of the model at roughly the same pace. Kevin Montgomery, a principle and the director of architecture in the North Carolina firm O’Brien/Atkins, noted that BIM discourages the “all hands on deck” flurry of production for a combination of reasons, both human and technological: Too many people attempting to modify the digital model simultaneously creates communication bottlenecks and bogs down the software.

To the extent that charrettes still occur in architecture firms beyond those of the profession’s stars, they happen when the firms enter competitions. In the firms of the architects I spoke with, participation in competitions did not correlate to office size: Even gigantic practices such as AECOM still seek commissions through competitions. As AECOM’s Weaver stated, intense spikes in production still occur for competitions that are “design and idea driven” and in which the presentations place “a premium on graphic quality.” The long hours required by these efforts are logged, predominantly, by the youngest members of the firms. AECOM tries to turn this into something positive, giving young employees the opportunity to make major design decisions in competition entries. Its Washington, D.C., offices have formalized this practice, forming a “Young Development Group” that actively searches for competitions that suit the firm’s capabilities. The group operates outside the normal decision-making hierarchy of the firm.

The increased influence of younger architects points to a potential positive aspect of both the old and the new forms of charrettes. When I asked Samuel Hunter, an assistant professor of psychology at Penn State who studies creativity, if he could identify any positive outcomes likely to come from charrettes, the first thing he mentioned was the “breaking down of social barriers” between the charrette participants.19 In fact, the guidelines for orchestrating the new high-performance charrettes stress the elimination of such barriers. Everyone is expected to contribute, and no one, regardless of title or position, is viewed as a superior.20 Charrette organizers also try to thwart compartmentalization by profession or design specialty,21 based on the assumption that the best design ideas can originate from outside any particular discipline.

Other psychological studies have reinforced the commonsense assumption that teams of designers that respect each other are more effective.22 AECOM’s Weaver told me of a situation from early in his professional career that I suspect is typical for many of us who began practicing in or before the 1980s. During a charrette that required the building of a model, one of the partners at the firm offered to perform the tedious but relatively mindless work of making a jig for some repetitive elements in the model. That “a guy with his name on the door would offer to just pitch in, rather than try to control things,” greatly increased the respect given to him by the young interns. It also made them feel more loyal to the firm. This raises a question in the comparison of the old and new charrettes: Does a day or two spent sharing a hotel meeting room at the kickoff of a project create the same depth of mutual respect and “leader role-modeling” as the time spent together in production “down to the wire” of a deadline?

A more important question is whether, even while recognizing the valid association of traditional charrettes with poor time management and exploitive labor practices, a case can be made for their survival in the profession. Such a case would have to depend on evidence that the old charrettes actually contributed to better designs. As a first step in making this case, we need to assess the impact of moving the charrette from the end to the beginning of the design process.

A potential problem I see with gathering a multidisciplinary group together at the start of a project may simply be that, absent fleshed-out design alternatives and reasonably detailed drawings and models to evaluate or debate, the discussions will be too abstract. Therefore, a high-performance charrette puts great emphasis on the ability of participants to verbalize their ideas. This could lead participants to favor the most eloquently expressed ideas, rather than the best. As Barry Schwartz, author of The Paradox of Choice, writes, “What is most easily put into words is not necessarily what is most important.”23

A second problem with conducting a charrette at the beginning of a project is that it may place too much weight on principles agreed on prior to a full-fledged design investigation. As most architects and many other designers are starting to recognize, it may take one or more failed design attempts to reveal the true complexities of a project.24 The assumption that all the relevant principles that could affect design decisions are known in advance is a problem-solving approach to design. As the language about high-performance hints, this approach greatly favors quantifiable aspects of a building. This design philosophy is preferred by engineering and business, because it rests on the application of accepted scientific principles. Its limitation, as Donald Schön eloquently put it, is that it cannot address new or unique design issues. “Because the unique case falls outside the categories of existing theory and technique, the practitioner cannot treat it as an instrumental problem to be solved by applying one set of the rules in her store of professional knowledge.”25 So while the new high-performance charrette may be effective in “problem-setting” (Schön’s term) and in start ing the process of breaking down social barriers on the design team, it may also impart the false sense that all the design issues are understood and that the charrette’s participants have chosen the most appropriate approach to the design.

Is there something about the traditional charrette that allows designers to better deal with the unexpected? A possible answer can be found in the charrette situation, popularized by the 1995 film Apollo 13. Several NASA engineers assemble in a room. Under intense pressure, with the astronauts’ lives on the line, they need to quickly figure out how to build a filter to remove CO2 from the damaged space capsule. One engineer dumps a box of parts on the table, telling the others that these are all the astronauts in the damaged space capsule have to work with.26 Contrary to what we would normally expect, the restrictive time and resource limitations seem to focus the attention of the engineers, who succeed in their task. In this and numerous other examples from popular culture, the participants were engaging in a design activity called bricolage—“working with what is at hand.” The term was popularized by anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who contrasted the engineering conception of design as problem-solving to the craftsman’s understanding that designs result from “tinkering.”27 The strength of the improvisational tinkering approach is that it can handle ill-defined problems, and that it realizes a “silver lining” from severe limitations (of time and/or available resources) by focusing attention on what will work, as opposed to what might be optimum under ideal conditions.

More recently, computer scientist Panos Louridas published an article in which he claims that all design can be understood as bricolage.28 He also talks about when these bricolage operations are most appropriate:

Once the designer has created his inventory, once he has decided on how to work and with what to work, the universe of his tools and materials is closed and he has to design with them. Of course, it may turn out that his inventory is not adequate; the designer will have to adapt it. But after each adaptation, the designer works with his inventory as closed. And the more he proceeds with his design, the more closed his inventory becomes: Changing it is costly and means rejecting parts of his work. It is easier to change it in the beginning than in the end of the design process.29

Extrapolating from the ideas of Lévi-Strauss, Schön, and Louridas, I am led to conclude that there are aspects of the old, end-of-the-project charrette as a design process that remain relevant and valuable. This helps explain their persistence in architecture schools and for competition entries in the profession that are “design and idea driven.” The two forms of the charrette stress alternative kinds of design thinking. The new charrette is founded on planning and problem-solving, the old on improvisation and bricolage. The new charrette aligns fairly well with what product designers call “concept generation.” A weakness of this process may be that it generates many possible design strategies without ever getting to a point, particularly in the absence of time pressure, when difficult tradeoffs between alternative strategies can be made.30 In the old charrette, choices among alternative strategies cannot be put off. At the eleventh hour, abstract concepts are rejected, modified, or ignored in favor of concrete solutions. The inventory of tools, principles, and materials in the new charrette is, initially, conceptually unlimited, while the inventory of resources in the old charrette is closed.

Yet it is also possible to argue that the two forms of the charrette can be complementary. The high-performance charrette starts the necessary process of “closing off” the designers’ inventory, and it introduces the various members of the project team to one another, setting the stage for the continued formation of social bonds. Furthermore, the case can be made that the shift to the bricolage mode of design thinking can be accomplished artificially rather than as the result of a crisis or of procrastination. We have all known accomplished designers who could keep to a schedule, but who never stayed up all night. Could it be that these are designers with the selfdiscipline to temporarily “close off” their inventory of resources and time in order to find concrete solutions? If so, this suggests that architectural educators might help train future architects in these skills, and that architecture firms could regularly organize relatively painless mini-charrettes.

The passing of the charrette ethos in professional architecture firms is a symptom of the ongoing industrialization of architectural practice. This process has provided architects with more predictability in their work schedules and fair compensation (at least for hourly workers) in the rare instances when they are called on to work overtime. It is also based on an ideology that defines time as a scarce resource, ignoring the fact that most architects enjoy designing—some so much that they do not mind doing it, occasionally, at 3 a.m. The industrialized practice of architecture has not resolved the inherent tension between architecture as a business and architecture as a creative act. And it never will.

The author would like to thank the architects who contributed their time and expertise to this article: Roger Duffy, FAIA; William Holloway, AIA; James Oleg Kruhly, FAIA; Kevin Montgomery, FAIA; Ed Weaver, AIA; and Todd Woodward, AIA. Thanks also to Samuel Hunter, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Psychology, Penn State University.