Accessibility Wars

In the storefront window of an otherwise unremarkable real-estate office a few blocks from our office in Downtown Brooklyn, one can witness—amid the clutter of posters advertising eye-poppingly priced triple mint brownstones, full-service starters, newswalk duplexes, and other picturesque Park Slope gems—the display in figure 2. Here are two ubiquitous signs advertising two very different—if not contradictory—sentiments. The sign on the right, advertising the office’s compliance with the 1968 Fair Housing Act’s mandate that it not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status, or national origin, is the open housing movement’s most prominent emblem. Its mandatory presence in real-estate offices, lending institutions, and apartment buildings across the country is the spoils of a patient, hard-fought victory in the ongoing war to make our communities more open. The product of the 1998’s Fair Housing Amendments Act, the bold “equal housing opportunity” sign stands as a proud soldier protecting our housing markets against the evil tyranny of discrimination.

The smaller sign on the left is a prominent emblem earned by the other side in this war—the side fighting for the right of our communities to be intolerant and unwelcoming. The sign says, essentially, that your constitutional right to assemble will not be tolerated here—not in my backyard!

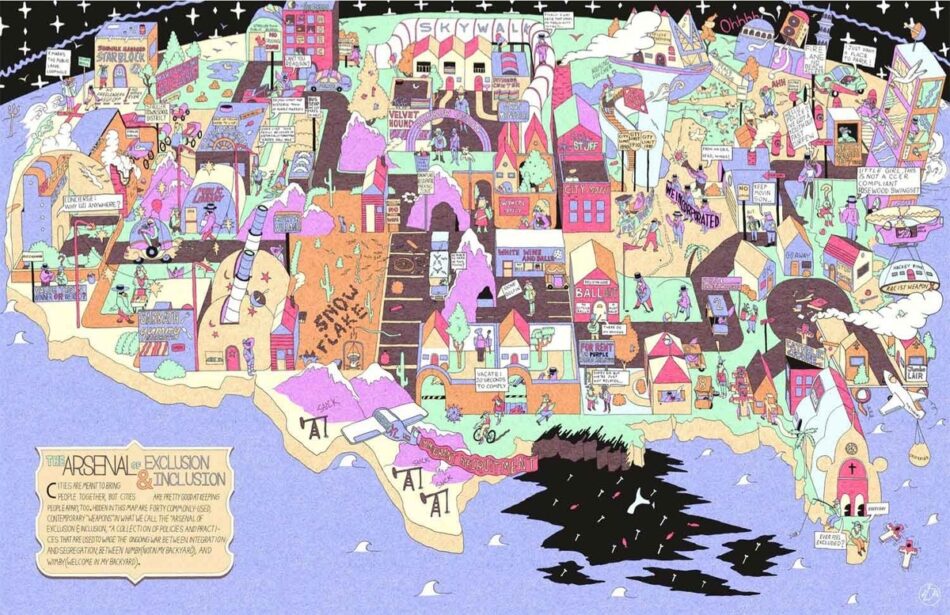

The contrasting sentiments displayed so prominently in this Flatbush Avenue storefront are emblematic of a larger contradiction that pervades the policies shaping the built environment in the United States. While there is no shortage of progressive policies that attempt to demolish barriers to “exclusive” communities and the everyday public spaces within those communities, neither is there a shortage of exclusionary policies, practices, and physical artifacts working hard to undermine them every day. We may have an amendment protecting citizens’ right to peacefully assemble, but we also have free speech zones that control political dissent by confining assembly and free speech to a designated zone (outside of which assembly and free speech are presumably illegal); teen curfews, loitering ordinances, and “no cruising” zones that define when and where teenagers can hang out; and police-patrolled barricades that prevent peaceful protesters from accessing parks that are allegedly free and open to the public. We have a Fair Housing Act that outlaws housing discrimination, but we also have blood relative ordinances that require tenants to be related by blood to their landlords,1 co-op communities that require would-be tenants to secure a letter of recommendation from an existing resident, and community care facilities ordinances that ban sober-living homes from residential neighborhoods. (This is in addition to widespread, run-of-the-mill exclusionary zoning policies that prohibit apartment buildings and prescribe minimum lot sizes and house prices that are too big and too expensive to be affordable by most people.) The Americans with Disabilities Act prescribes design standards to ensure that our built environment is accessible to the elderly and disabled, but we also privilege auto-centric transportation policies that produce menacing, pedestrian-unfriendly intersections and that often result in a lack of public transportation options that keep the elderly and disabled in their homes.

Indeed, when we look at the complicated legacies of policies that attempt to open the built environment and demolish barriers to accessibility, we learn that they do not necessarily work the way they are supposed to. Loopholes abound. Many policies begin with great promise, but are quickly watered down, often by counter-policies, practices, and physical artifacts devised to neuter them. For example, thanks to the Fair Housing Act, a developer who wants to build a community for Catholics cannot explicitly deny access to non-Catholics, but the developer does nothing illegal when he builds a Catholic church at the center of a gated community and requires all residents to pay dues to maintain it2—an “exclusionary amenity” that creates a disincentive for non-Catholics.3 Thanks to the public trust doctrine, suburban beachfront towns in most states cannot explicitly restrict access to their beaches, but these towns do not necessarily violate the law when they institute strict residential parking programs on their streets, post phony Private Beach signs on their beaches, or landscape their beach access points to look like front yards.4 And thanks to the First Amendment, an owner of a convenience store cannot explicitly prevent skateboarders from congregating on the sidewalk in front of her store, but she does nothing illegal when she blares the smooth sounds of Kenny G from roof-mounted speakers in the hopes of scaring them away.

Historical examples of how policies designed for one purpose proved useful for another are plentiful: Chicago’s Neighborhood Composition Rule, which required that the racial makeup of a public housing development match the racial composition of the surrounding neighborhood, was proposed by progressives who feared that whites would reclaim black land and build public housing for whites only. As Bradford Hunt points out, however, it did not take long for the rule to be successfully appropriated by conservatives wishing to create racially segregated public housing.5 Neighborhood-wide House For Sale sign bans were pioneered by blockbusting-fighting civil rights groups and integrationists who feared that unscrupulous, blockbusting real-estate brokers were using the signs to pedal panic in white neighborhoods and incite white flight, but the ban was quickly appropriated by racists to maintain or promote segregation. The strategy? Taking away a homeowner’s right to sell his or her house with a simple for sale sign would make the homeowner more likely to list the home through brokers, who, through their multiple listing service, segregated classifieds, and racist code of ethics, would ensure that a white-owned home would not be sold to a black family and vice versa.

This gap between intent and effect suggests what attorneys know all too well—namely, that how a policy plays out is as important as the policy itself. As the examples above make plain, those of us who are working to build more open cities have to first of all be vigilant and remain on the lookout for the counter-policies, practices, and physical artifacts that pop up and undermine accessibility-promoting policies. And because these tend to take some surprising forms (churches, Kenny G, landscaped yards, among others), we sometimes have to see past appearances. In California, where state law prohibits sex offenders from living within 2,000 feet of a park or school, for example, communities across Los Angeles have started building “parks”—some of them just a few square feet—in spaces that fall outside these 2,000-feet radii, effectively forcing sex offenders to leave town. We have to get good at knowing when a park is a “park.”

But two can play this game: Exclusionary policies can be watered down or neutered by counter-policies, practices, and physical artifacts, too. Indeed, this suggests a more meaningful role for “tactical” urbanism, that, rather than naively chasing vibrancy for vibrancy’s sake, exploits loopholes to open the city. Consider the simple example of the New York City street vendor: The arbitrary (and extremely low) cap the NYC Department of Consumer Affairs maintains on the number of street vending licenses excludes would-be vendors; however, because the city’s free speech regulations protect the sale of books, booksellers are not required to obtain the permit. The books you sometimes see for sale on the street next to the other, more profitable wares? They are in many instances the artifact that enables the vendor to legally vend in public. Occupy Wall Street offers another example with the occupation of Zuccotti Park, a privately owned public space that, unlike a city-owned public space, can draft and enforce its own rules of operation. Zuccotti Park happened to have had very lax rules: One could not skateboard, roller skate, or bike through the park, but when the protest began, there were no rules prohibiting camping or lying down. We might also consider local immigration ordinances: When efforts by the federal government to pass a comprehensive immigration reform bill failed, local governments took matters into their own hands and created their own local ordinances. While the earliest of these were exclusionary in nature (examples include ordinances that made it illegal to rent to unauthorized immigrants, hire an undocumented worker, or occupy a dwelling unit with extended families), anger spurred more immigrant-friendly communities to invent things like municipal ID cards and immigrant safe zones, and in some instances, actively recruit immigrants with promises of tolerance and opportunity.

The resourcefulness of the exclusionary impulse suggests that we will not have truly open cities until we work on the will in addition to the way—until people are less likely to exercise the exclusionary impulse in the first place. And of course we need to continue to produce and enforce progressive, accessibility-promoting legislation. But in the meantime, it would not hurt us to be a bit more creative and resourceful about how we exercise the inclusionary impulse.