When Walls Are Doors

My favorite book as a child was called Story Number 2. Written by the absurdist playwright Eugene Ionesco, it tells the tale of the logical Josette and her enigmatic father, who gives her a lesson in “the real meaning of words”:

““The ceiling is called floor. The floor is called ceiling. The wall is called a door,” Papa explains matter-of-factly.”

““A chair is a window. The window is a penholder. A pillow is a piece of bread. Bread is a bedside rug.””

Catching on, Josette begins to concoct a scenario based on her father’s reasoning, until she stumbles on the word “pictures” and asks him to translate. Pausing, he answers thoughtfully: “Pictures … One mustn’t say pictures! One must say pictures.”

Story Number 2 destabilized language—and with it, the physical world. But the more I reread, and reenacted, Ionesco’s nonsense, the more I unlearned the paradigms of my kindergarten reality. Making sense was not the point; not making sense was. Misunderstanding was at the crux of Story Number 2. It was about scrambled codes and disintegrating messages; about snags along the route from sender to receiver.

Do you read me?

This question, originally used in radio communication, generated the 38th issue of Harvard Design Magazine. It sets the stage for the magazine’s new direction—one that invites “reading” across disciplinary boundaries, and stakes out an expanded arena for architecture and design dialogue. There’s a suspense as “Do you read me?” hangs in the air. It anticipates a response: “Roger,” “Loud and clear!”—or, alternatively, a disruption—“You’re breaking up,” “I’m losing you …,” or no answer at all.

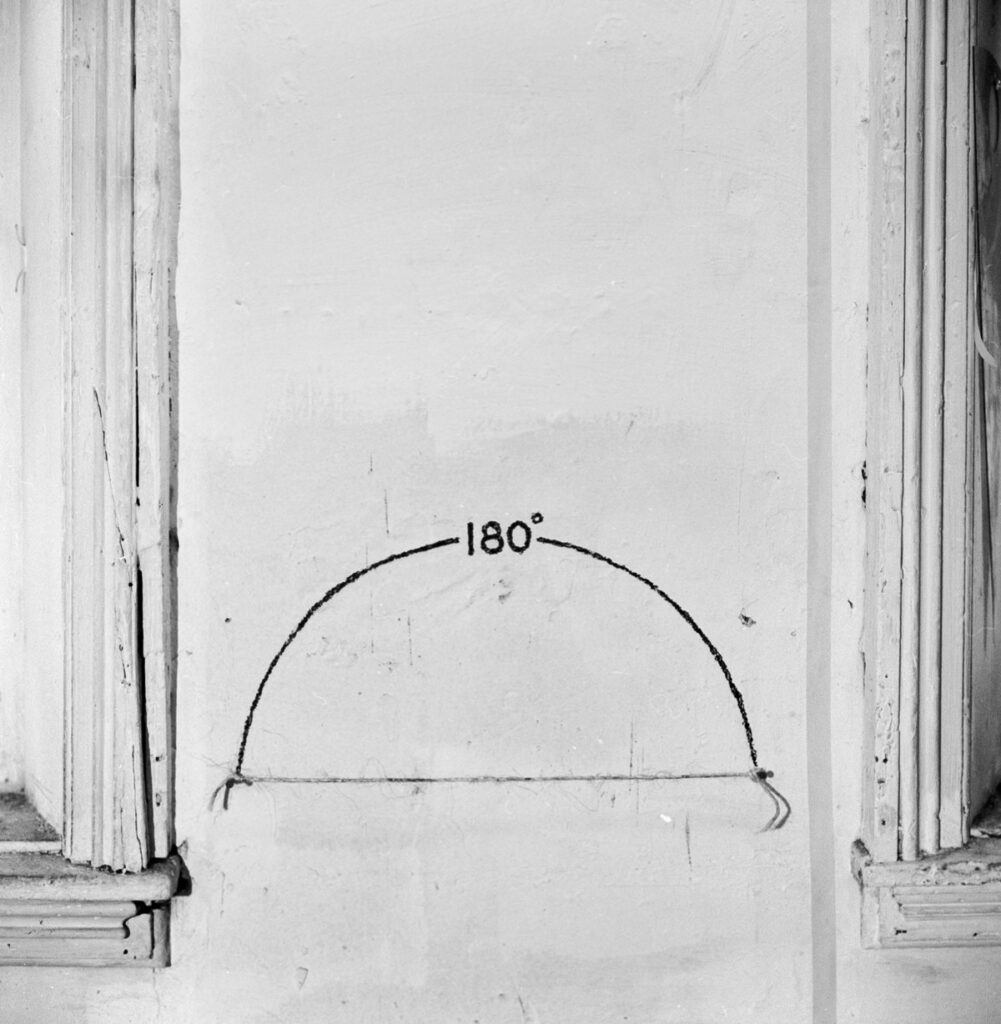

This issue is about reading and misreading, and the role of design in streamlining or complicating the exchange between sender and receiver, writer and reader, maker and user. It examines the symbols, materials, and technologies that shape and transmit messages between strangers, and across disciplines and media. Whether written or rendered, engineered or enacted, both message and messenger are designed, and it is the relation between design and comprehension that is explored here.

Beyond the conscious exchange of constructing and deciphering messages, we are all constantly being objectified and “read” as data. While we offer our identities as moldable content and marketing fodder with every click; while our words, wants, and whereabouts are tracked by both “friends” and unknown readers; we might wonder whether misunderstanding, or inscrutability, could be something to aspire to.

Once released, all messages are objects of unstable meaning. As much as we try to make use of shared codes and protocols, their composition, transmission, reception, and interpretation are subjective moments. This issue of Harvard Design Magazine suggests that the role of design is not just to construct certitudes, to clarify, but also to enable more nuanced realities to coexist. To allow for a wall to be a wall, but also a door, and for pictures to be pictures—or pictures.