From the Old Family—to the New

Vasya was doubly ecstatic. She had just left her philandering common-law husband, Vladimir, and she was pregnant. “She walked back along the street, smiling. A baby! How wonderful! She’d be a model mother! After all, it should be possible to bring up a child in true communist fashion. There was no reason for women to set up with husbands, in families, if it merely tied them to the cooking and domestic chores. They’d get a crêche going, and re-purchase a children’s hostel. It would be a demonstration of child rearing to everyone. And as she began to think about it, Vladimir vanished from her thoughts as though he had no connection with the baby.”1

In Love of Worker Bees, a collection of stories from 1923, Vasya represented the new Soviet woman: single, confident, and committed to a life of edifying political-agitational work. Worker first, mother second, wife never again. Author Alexandra Kollontai, former director of the Women’s

Department of the Communist Party (Zhenotdel), used fiction to promote new social relations under Socialism.

In explicitly political texts like “Communism and the Family,” Kollontai damned outdated relational conditions. “There is no escaping the fact: the old type of family has had its day,” she wrote in 1920. “In place of the individual and egoistic family, a great universal family of workers will develop.”2 Two new units of social measure emerge in Kollontai’s texts to replace the nuclear family. First is the individual worker, untethered by blood or marital ties. Second is the aggregate collective comprised of many individuals working toward the same goal—the “free and equal association of producers” envisioned by Friedrich Engels.3 Like the institution of the state under complete Communism, the family would “wither away not because it is being forcibly destroyed by the state, but because the family ceases to be a necessity.”4

What are the spatial implications of this redefined, Socialist family? How did Soviet architects process the political debates about reorganizing the everyday life of workers like Vasya? What were the architectural tasks prompted by these new units of social measure? Finally, what can the intense period following the Bolshevik victory in Russia contribute to contemporary debates about changing family structures and the spaces they occupy? Although theorists like Kollontai established the early

intellectual foundations for Socialist family life, the flurry of architectural work that addressed questions of Soviet domesticity occurred later, during the first Five-Year Plan for economic development (1928–1932). Under the Plan, the Soviet state expended enormous capital to construct hundreds of new industrial-residential complexes on tabula rasa sites. The time was ripe for innovative housing solutions that could do double duty: house the labor pool and accelerate the transformation from capitalist to Socialist forms of domesticity.

Space and Habit

To understand the importance of the built environment for early Soviet theorists, we must begin with the Marxist postulate that matter determines consciousness. “On the question of everyday life (byt),” wrote Leon Trotsky in 1923, “it is patently obvious that each individual is the product of his environment rather than his creator.”5 Logic follows that if space shapes behavior, everyday environments are key sites of political intervention. To ensure the ascendance of a new everyday life (novyi byt), traditional household relations and responsibilities would have to be completely reconceived, Trotsky argued. Women would have to be relieved of housekeeping and childcare duties, and freed from the bonds of marriage. New Socialist institutions such as canteens, laundries, and nurseries would permit Soviet women to practice domestic independence—and, crucially, to enter the workforce.

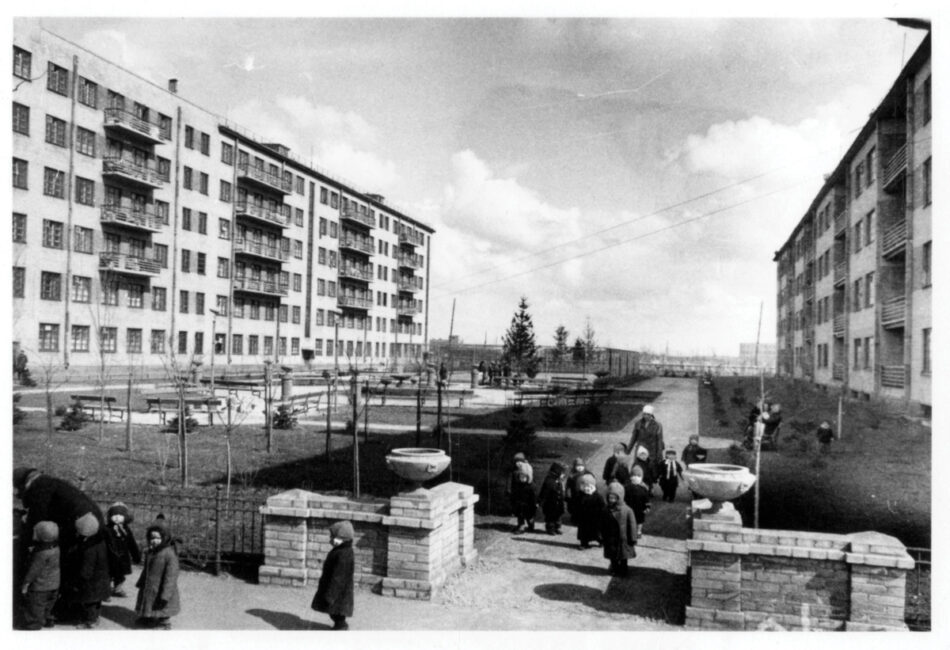

During the New Economic Policy (1921–1927) workers and peasants flooded into cities that were ill equipped to handle the population influx. Since property had been socialized in 1917, the Soviet state alone was responsible for addressing the housing shortfall. Yet building projects were stymied by the state’s financial instability and insufficient project management infrastructure. Stopgap solutions like the communal apartment (kommunalka) were put in place instead: extended families were granted a single subdivided room within a prerevolutionary bourgeois or aristocratic residence. Common entry, corridor, kitchen, and bathroom facilities became battlefields for interpersonal conflict.6 Newly arrived peasants who lived in such overcrowded housing contributed to a “ruralization” (okrest’ianivanie) of Soviet cities.7 Village moral codes became entrenched in urban contexts. These were inauspicious conditions for crafting new Soviet citizens.

Socialist Cities, Socialist Individuals

State interest in housing design spiked at the onset of the first Five-Year Plan. Many of the sites earmarked by the Soviet government for rapid industrial expansion were remote territories that could host new kinds of construction, yet housing typologies had changed little during the preceding decade. Leonid Sabsovich, a high-ranking economist on the State Planning Committee (or Gosplan), seized the opportunity to advocate for a comprehensive overhaul of spatial practices. The moment had arrived, he argued, to design the true Socialist city, an environment that would transform the residents it housed: “Everything that currently creates the need for an individual household and binds a man to a woman should be completely eliminated in the Socialist way of life.”8 Sabsovich waged his campaign in newspaper articles, books, and public forums. He also engaged the architectural avant-garde to spatialize his ideas.

Sabsovich’s best-known text is Socialist Cities from 1929, which set the design tasks for new industrial-residential complexes. In the book, he advocated for the construction of “housing combines” (zhilkombinaty), self-sufficient units comprised of residential and service buildings designed for two- to three thousand residents. Factory kitchens, crèches, children’s dormitories, mechanized laundries, and clothing repair shops within each combine were to liberate women from all household tasks.

In his discussion of housing types appropriate to the Socialist city, Sabsovich emphasized the interdependence of the two demographic units of measure under Socialism—the individual worker and the collective:

In the socialist city, houses should be constructed in such a way that they provide the greatest convenience for the worker’s collective life, collective work, and collective recreation. They should also provide the most comfortable possible conditions for individual work and individual leisure. These houses should not have separate apartments with kitchens, pantries, etc. for individual domestic use, since all of the worker’s everyday needs will be completely socialized. In addition, they should not include space for private family life, because the idea of family, as we now know it, will no longer exist. In place of the closed, isolated family unit we will have the “collective family” of workers, in which isolation will have no place.9

In his prescription for Socialist housing, Sabsovich summarily eradicated the spaces in which the middle relational scale of the nuclear family might flourish, like the kitchen table or sitting area within the apartment. All socializing and recreating were to occur in “social condensing” spaces in the public realm, like canteens and worker clubs. Workers either engaged in solo work and leisure in their single rooms or they immersed themselves in the collective. Public and private were strictly separated.

But where were the children—the future Socialist individuals—in this new arrangement? Without exception, they lived separately from the people who spawned them. “The question of joint dwelling for children and their parents can only be answered in the negative,” stressed Sabsovich. “Infants are best located in special buildings where the mothers can visit for feeding. […] Pre-school and school-age children should spend most of their time in spaces designed for their learning, productive work, and leisure. It is clearly pointless to provide space for them in the same dwelling as their parents, where they would return at night. Therefore, house-communes should only be built for adults.”10 Children were to be separated by developmental stage and accommodated in state-run dormitories. Children’s dorms would be located within the housing combine, near the adult house-communes but independent from them.

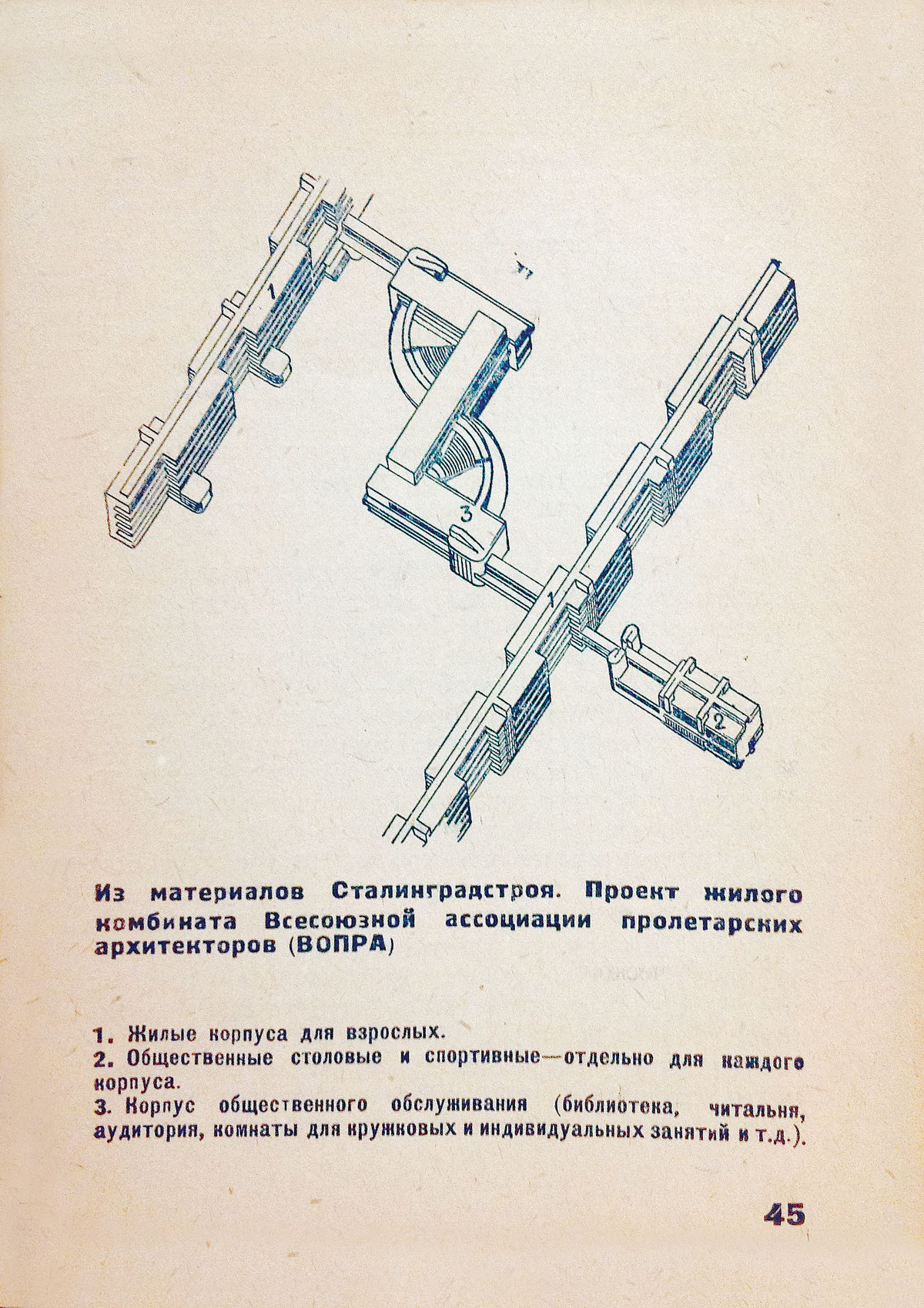

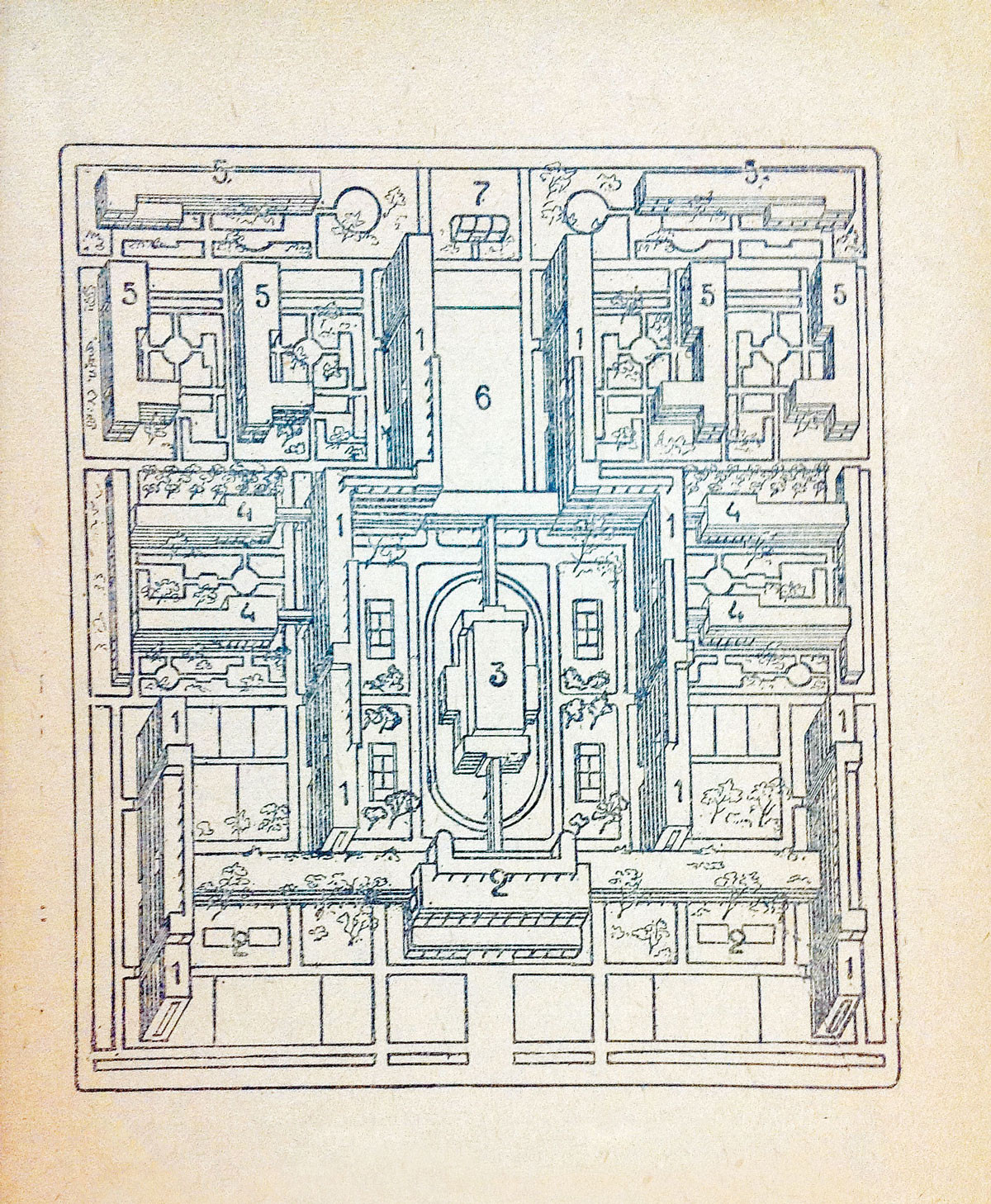

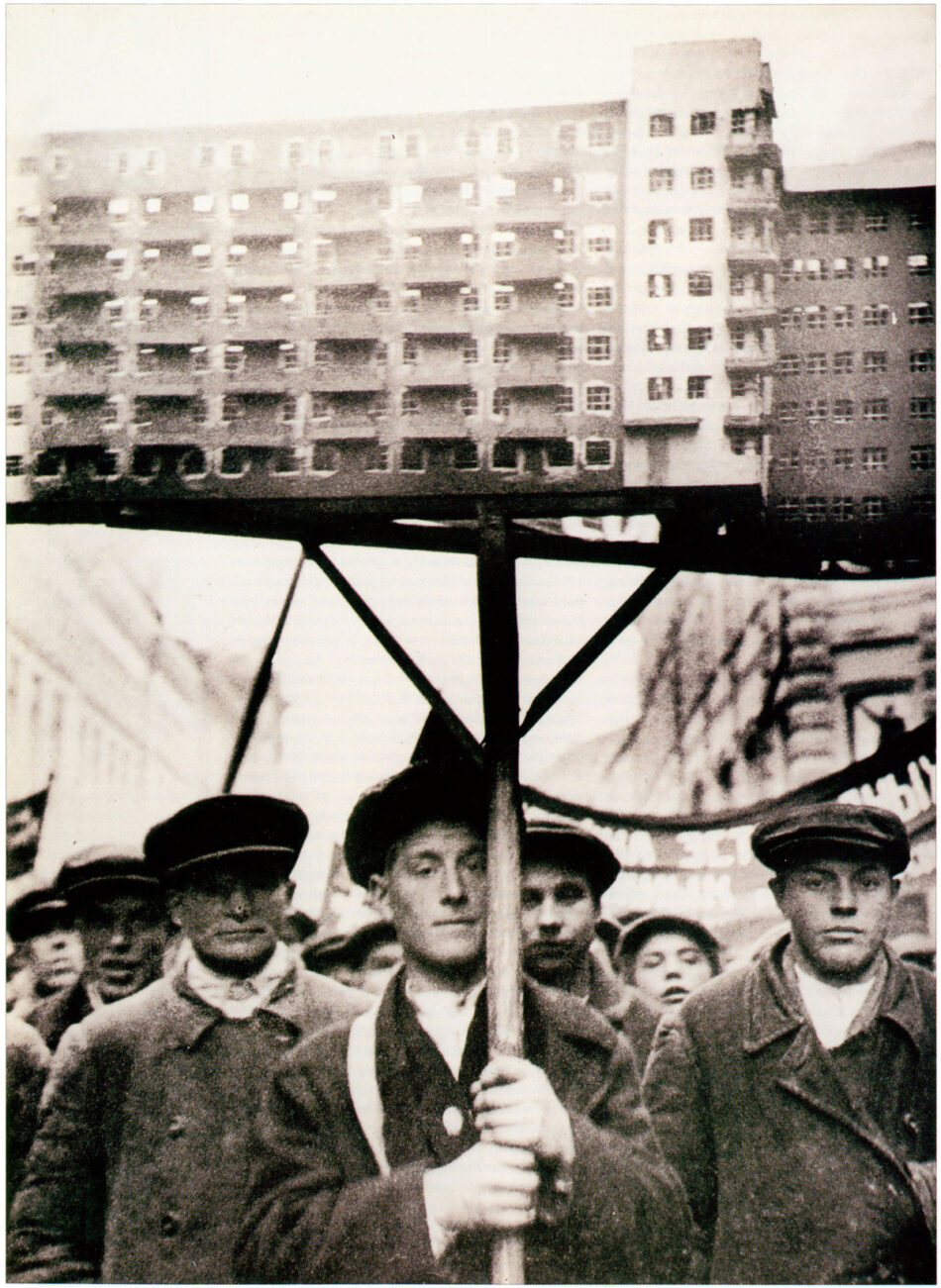

Illustrations for Sabsovich’s text demonstrate the architectural effects of programmatic and demographic atomization. All projects featured were competition entries for Stalingradstroi, a Socialist city attached to the Ford auto plant in Stalingrad.11 The housing combine designed by the Vesnin brothers was a porous, symmetrically composed megablock. Discrete programs were housed in freestanding buildings. Five-story residential wings were linked to connected by heated, elevated walkways that connected to the children’s home for infants and toddlers; older children were to live in proximate but unconnected dormitories. The sports complex and communal services wing—the social condensers—were centrally located and equally accessible to all demographic categories. In another project, by the VOPRA group, bar buildings intersected and slipped by one another as they spun off, Suprematist-style, on autonomous trajectories. As in the Vesnin project, housing was separated from dining, which was itself separated from other communal services. There is no programmatic both-and in the housing combines. They “glory in separation.”12

Living Cell

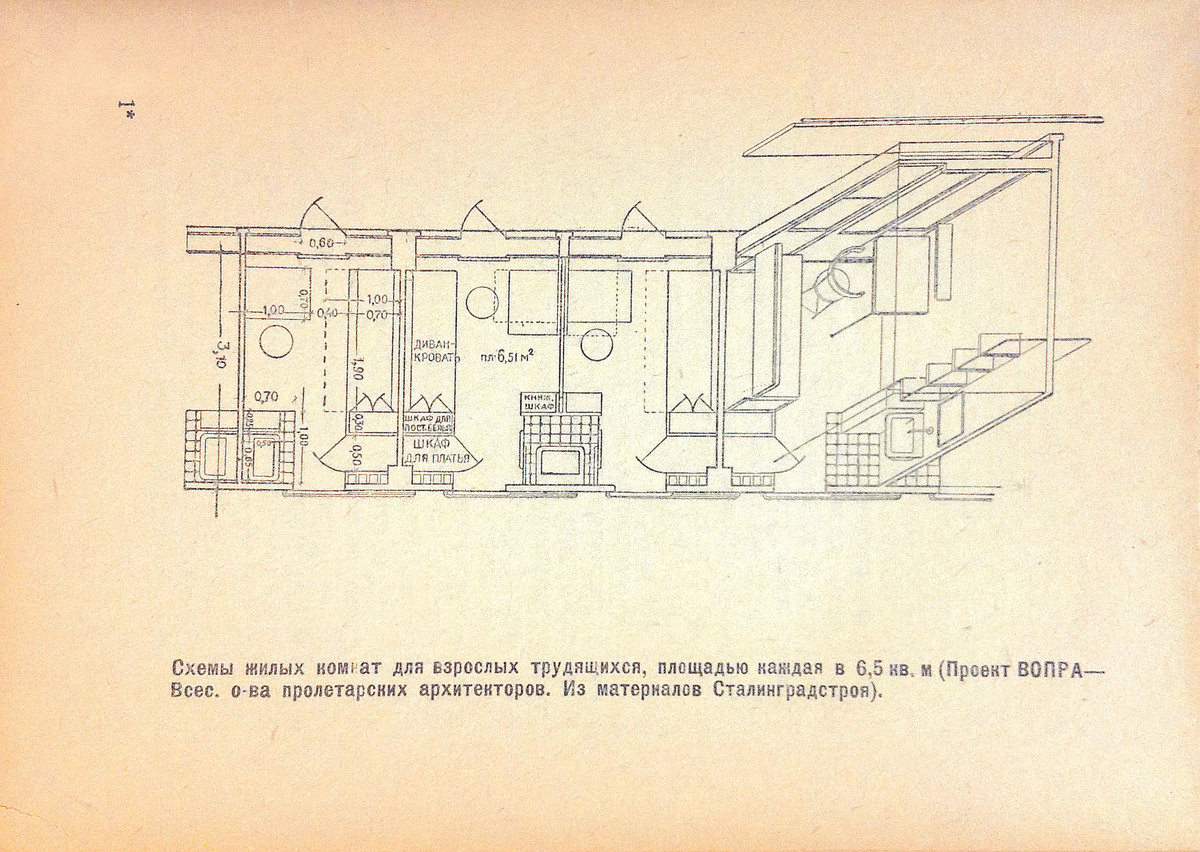

The living cell (zhiliashchik) was the architectural analog of the individual worker. Its repetition and amalgamation created the collective Socialist city. “The provision of a separate room for each worker should be carried out consistently,” Sabsovich explained. “Some of these rooms (or maybe all) must have a door or sliding partition to connect to adjoining rooms through interior circulation, if the husband and wife wish. But there should be no joint living space for husbands and wives.”13 Each worker was granted a space of total privacy to balance the extreme communality of Socialist life.

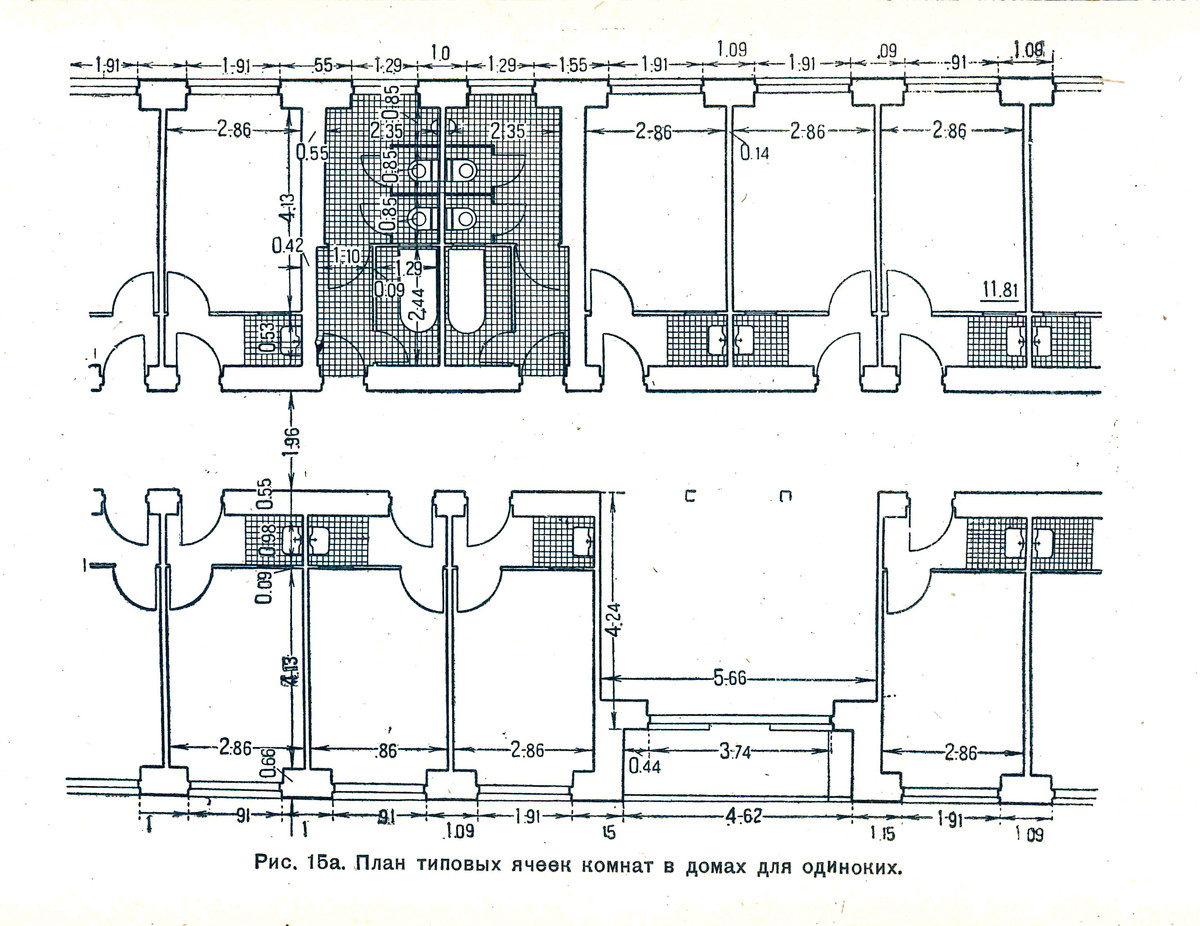

Sabsovich conceded that his one-unit-per-worker proposition might be seen as profligate, but the economics were feasible, he argued, if housing production were structured as a simple formula. Building area and costs would be set by state fiscal controls, so that the sole variable was the program mix within the housing combine. Thus began the budgetary tug-of-war between living cell and social program. In contrast to the state-mandated minimum of nine square meters per person, Sabsovich proposed that “it is possible to build a room of 5 square meters with sufficient amenities, while also reserving 5 square meters of communal space for each member of the population.”14 Tiny private units, like those illustrated in the pages of Socialist Cities, were permissible when supplemented by a robust public realm. Soviet architects had reached this conclusion even earlier. In a 1927 competition for communal housing sponsored by the avant-garde architectural journal SA (Sovremennaia Arkhitektura), architect Moisei Ginzburg noted that communal programs not only permitted transition to a fully Socialist sensibility, they could also reduce construction costs on a unit-by-unit basis.15 The architectural community, and later Sabsovich, recognized that custom-designed, collapsible furniture was essential to make these units livable. Innovative furniture research dovetailed with living cell design.

The living cell was more than a theoretical proposition; it was mobilized. By late 1929, the state banking system instituted strict borrowing conditions for housing projects that were pegged to byt-transforming sociocultural amenities.16 The architectural brief for the residential sector of the Kharkiv Tractor Plant, a Socialist city designed in accordance with these funding stipulations, reads like a page from Sabsovich’s book.17 Residents would be organized in housing combines, each with a total population of 1,500. Living quarters would be designed for and separated by demographic characteristics—children aged 8 to 14, for example, would live in groups of two to five in single rooms. Because of the intensely planned communal services, adult living cells would be constructed without kitchens. Overall, the architecture would foster a “painless and quick resolution to the task of transition to complete socialization.”18

A five-story building of living cells was completed for the Kharkiv Tractor Plant in 1930. Plans show that the door to each 9.45-foot-wide living cell opened onto a small foyer with a personal sink and connecting conjugal door. Two gendered bathrooms off the corridor held a bathtub and toilets for common use. Common seating areas and balconies were inserted at regular intervals along the residential corridors, and worker clubs and canteens were constructed to serve dining and recreating needs. There were no private kitchens.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the cells and the entire sociocultural infrastructure of the Tractor Plant’s residential sector were used as the residents, not the architects or their state clients, wished. Hotplates were smuggled into the kitchenless cells. Interior walls were punched through to create family units. And the elementary boarding school had to be repurposed as a normative day school when, according to local lore, not a single parent volunteered a child for state parenting.19

The family unit did not wither away in the Soviet Union, and the living cell did not replace the apartment. By the spring of 1930, the Central Committee of the Communist Party issued a resolution denouncing “utopian” urban schemes, especially those that tried to force Socialist habits. Sabsovich was reproached by name.20 The revised theory of the state asserted that Soviet cities became Socialist “from the very moment of the October Revolution,” and that regular maintenance of existing housing and improved urban infrastructure should be the first priorities of the state.21 Small housing units were built for reasons of frugality, not ideology, and by the mid-1930s, the nuclear family was reinstated as the primary economic unit in the Soviet Union.22

The public components of the living cell experiment persisted, however. Canteens, worker clubs, libraries, sport facilities, theaters, and state-run day care—all of these socialized programs flourished and became important supplements to Soviet domestic life. If the prerevolutionary family structure was not entirely eclipsed, at least the members of the Socialist family could seek relief from close domestic quarters in the programmatically enriched public realm.

Epilogue: The Micro-Unit

In 2014, the Urban Land Institute (ULI) released a report entitled “The Macro View on Micro Units,” which explored the market emergence of the “purpose-built, typically urban small studio or one-bedroom using efficient design to appear larger than it is.”23 According to ULI, the two main reasons for the rise of the micro-unit (defined as between 280 and 450 square feet) are the exorbitant cost of living in desirable urban areas and the increase of single-person households, which now compose over 50 percent of the US population.24

The societal motives behind the Soviet living cell and the American micro-unit differ greatly, of course. The living cell was devised for an ideological goal, to explode traditional family structures. Once Soviet citizens were separated into independent residential spaces, the theory held, sticky relational habits would dissolve and each solo occupant could be reprogrammed to ally him- or herself with the collective rather than kin. The micro-unit is the result of economic exigencies. According to ULI, a large number of the micro-unit residents are recovering from “delayed-onset-adult syndrome,” or postponed financial independence, a problem exacerbated by the past decade’s economic downturn. The micro-unit is the solitary space in which the first-time renter may finally transform him- or herself into a self-sustaining member of society.

Whether economics or ideology prompted its invention, the architecture of the micro-unit closely mirrors the Soviet living cell. The size of the micro-unit is carefully calibrated to accommodate a single person who has accumulated little material baggage. The ULI research revealed that at the optimal size (approximately 300 square feet) there was a “need to have flexible furniture systems and adequate storage for units this small to be workable.”25 A complementary market in clever: and convertible kitchen and furniture design has arisen in response to the micro-unit’s spatial constraints. Micro-unit buildings also provide extensive communal areas to compensate for spatial economy within the unit. Fitness areas and cafés—typical multiunit building amenities—are supplemented in micro-unit buildings by common “living rooms” on each floor, rooftop gardens, and large catering kitchens. Common areas in micro-unit buildings are for socializing and coworking only—they are spaces, not programs. Developers should take note, however: shared domestic programs of the Soviet housing combine, like the canteen and public laundry, just might flourish under 21st-century capitalism.

Minimal living spaces nonetheless serve a similar function in both early Soviet and contemporary American societies: the cell is an apparatus that transforms its predominantly young, single occupant from family member to autonomous citizen. The interpersonal bonds of the nuclear family are severed in the ascetic single room, be it in Kharkiv, San Francisco, or La Tourette. Social transmogrification is made possible by enclosure and solitude that finds relief, finally, in its antipode: communal space and collective life. Once self-actualization has run its natural course, the nuclear family may again emerge as a viable unit of social measure. The living cell and the micro-unit need be not terminal spaces of habitation. They could just be the way station, the em dash that separates the old family—from the new.

Essay title taken from an article by Leon Trotsky, “Ot Staroi Sem’i— K Novoi” [From the old family—to the new], Pravda, July 13, 1923.

1 Alexandra Kollontai, Love of Worker Bees (1923), trans. Cathy Porter (Chicago: Academy Press, 1978), 175. All translations by author, unless otherwise noted. 2 Alexandra Kollontai, “Communism and the Family” (1920), in Selected Writings of AlexandraKollontai, trans. Alix Holt (London: Allison & Busby, 1977), 258–59.

3. Frederick Engels, “The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State” (1884), trans. Alick West (1942), rev. ed. 2010, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1884/origin-family/.

4 Kollontai, “Communism and the Family,” 258–59. 5 Leon Trotsky, “Chtoby Perestroit Byt, Nado Poznat’ Ego” [In order to rebuild everyday life, it is necessary to know it], Pravda, July 11, 1923. For an excellent introduction to theory of everyday Socialist space, see David Crowley and Susan Emily Reid, Socialist Spaces: Sites of Everyday Life in the Eastern Bloc (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2002), 2–11. 6 For a full description of the sociology and psychology of the Soviet era communal apartment, see Svetlana Boym, “Living in Common Places: The Communal Apartment,” in Common Places: Mythologies of Everyday Life in Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994), 121–65. 7 Moshe Lewin, The Making of the Soviet System: Essays in the Social History of Interwar Russia(London: Methuen, 1985), 220. 8 Leonid M. Sabsovich, Sotsialisticheskie goroda (Moscow: Gosizdat RSFSR Moskovskii rabochii, 1930), 68. 9 Ibid.; all italics in original. 10 Ibid., 46–47. 11 For more on the Stalingradstroi project, see Heather D. DeHaan, Stalinist City Planning: Professionals, Performance, and Power (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013); and Richard Cartwright Austin, Building Utopia: Erecting Russia’s First Modern City, 1930 (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2004). 12 As Robert Venturi noted in a critique many years later, separation and articulation of programmatic elements was a hallmark of architectural modernism, a project to which these housing combines certainly belong. Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, 2nd ed. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1977), 35. 13 Sabsovich, Sotsialisticheskie goroda, 49. 14 In 1929, the Russian Republic had set the minimum living area per person at nine square meters, but this area allocation functioned in practice as a maximum to which architects were expected to design. The living cell design examples in Socialist Cities fell below this threshold at eight and six and half square meters. See Steven E. Harris, Communism on Tomorrow Street: Mass Housing and Everyday Life after Stalin (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2013), 51. Quote from Sabsovich, Sotsialisticheskie goroda, 52. 15 Moisei Ia. Ginzburg, “Kommunal’nyi Dom A1,” Sovremennaia Arkhitektura, no. 4–5 (1927): 130. 16 “Protokol’noe postanovlenie SNK SSSR: Predlozhitiu tsekombanku pri priniatii proektov k kreditovaniiu zhilstroitel’stva v 1929/30” [Protocol of the SNK USSR: Requirements of the Central State Bank when lending for housing construction projects in 1929/30], Central State Archives of Supreme Bodies of Power and Government of Ukraine (TsDAVO), f.5, o.3, d.2085, l.27 (1930). 17 Although the name of the city is Kharkov in Russian, here I use the current Ukrainian spelling, Kharkiv. 18 “Programma: Zadaniia na sostavlenie eskiznykh proektov zadanii zhilogo sektora sotsialisticheskogo goroda i traktornogo kombinata vozle gor. Khar’kova” [Program: Tasks for the preparation of preliminary designs for the residential sector of the Socialist city near the tractor plant in Kharkov], Central State Archives of Supreme Bodies of Power and Government of Ukraine (TsDAVO), f.5, o.3, d.2085, l.13 (1930). 19 The present school principal shared this anecdote with the author on February 2, 2012. 20 Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik), “O Rabote Po Perestroike Byta (Postanovlenie Tsk Rkp(B) Ot 16 Maia 1930 Goda)” [On the work to reconstruct everyday life (resolution by the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) from 16 May 1930)], Pravda, May 29, 1930, 5. 21 Lazar Moiseevich Kaganovich, Socialist Reconstruction of Moscow and Other Cities in the U.S.S.R, vol. 159 (New York: International Publishers, 1931), 25, 53. 22 Anton Semenovich Makarenko, The Collective Family: A Handbook for Russian Parents (1937), trans. Robert Daglish (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1967), 28. 23 Urban Land Institute Multifamily Housing Councils, “The Macro View on Micro Units” (2014), http://uli.org/wp-content/uploads/ULI-Documents/MicroUnit_full_rev_2015.pdf. 24 Tim Worstall, “The Us Is Becoming More European: Half of Adult Americans Are Now Single,” Forbes, September 11, 2014, http://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2014/09/11/the-us-is-becoming-more-european-half-of-adult-am…. 25 Urban Land Institute Multifamily Housing Councils, “The Macro View on Micro Units,” 25.

Christina E. Crawford is an architect, urban designer, and historian of urban form whose work focuses on design strategies particular to transitional periods. Crawford is completing her PhD at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design with a project on early Soviet urban theory and practice.