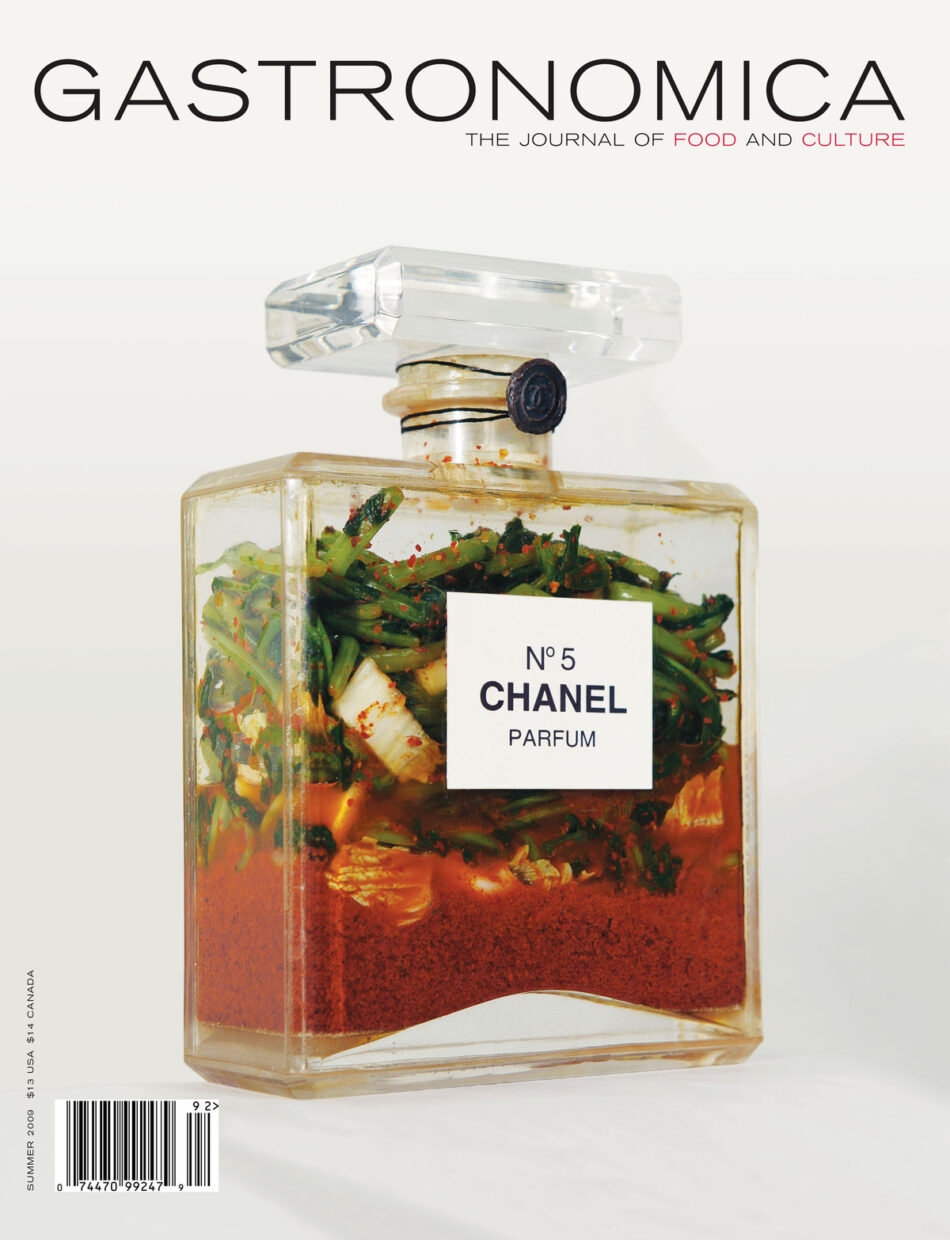

Christina E. Crawford

You’re a professor of Russian, an acclaimed cookbook writer, founding editor of Gastronomica, and now editor in chief of a new magazine on food preservation called Cured. How are these interests linked?

Darra Goldstein

When I started studying Russian in college, I found myself captivated by the descriptions of food in Russian literature. In Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago (1973), he writes about being in a prison cell. He wanted desperately to read literature. Because he was in a privileged situation, he was able to get books from the prison library. He had this amazing line: “Get away from me, Gogol! Get away from me, Chekhov, too! They both had too much food in their books.” Essayist Tatyana Tolstaya has suggested that the literary focus on food is actually sublimation due to censorship. Writing about sex wasn’t allowed, so the erotic was expressed through food. Take Anton Chekhov’s short story “The Siren”—men are caressing this kulebiaka (a savory pie with a grammatically feminine ending) and weeping with desire. The whole thing is hilarious—unless, of course, you were in the Gulag.

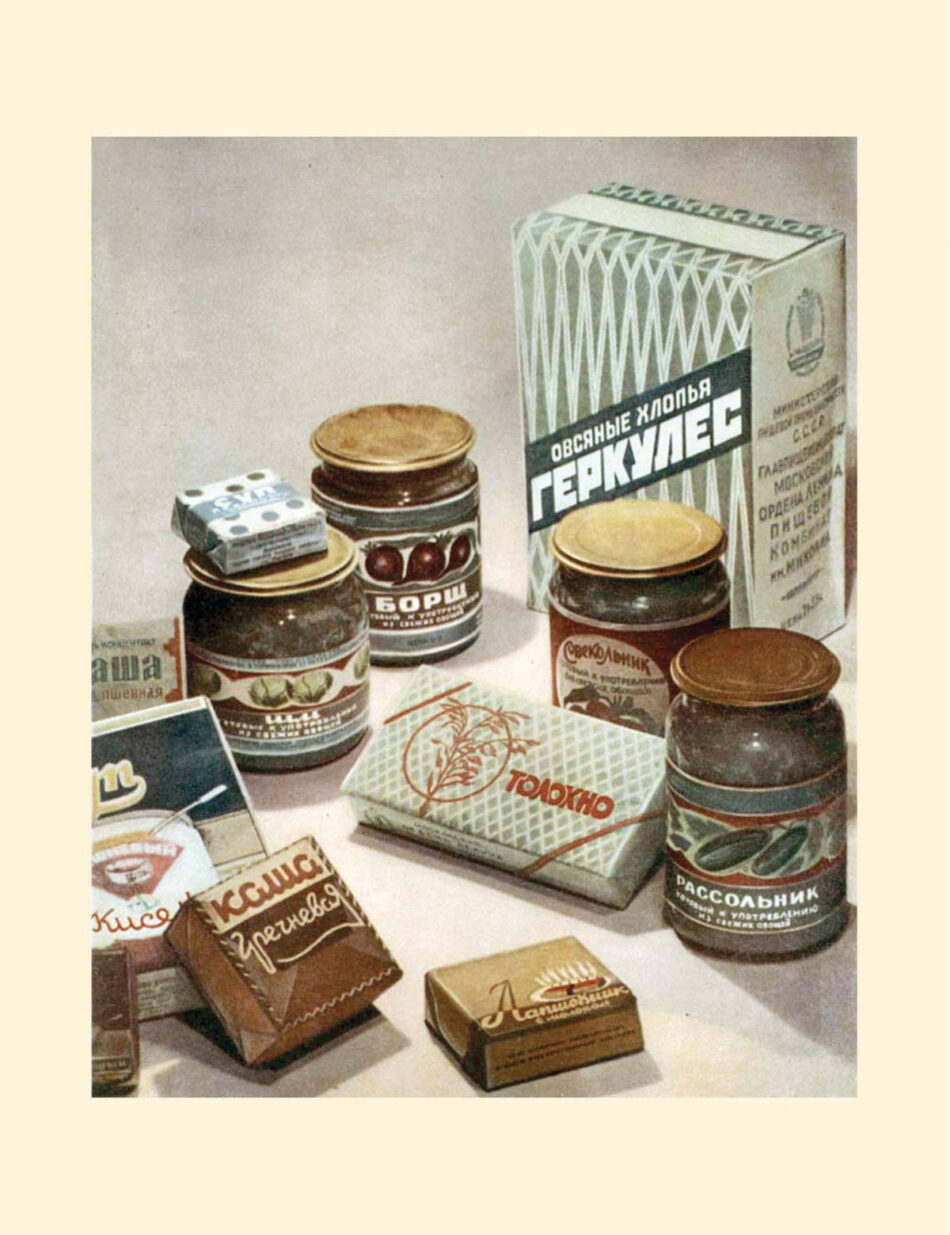

When I first traveled to the Soviet Union, in 1972, there was basically no food. I mean, there were standard provisions—sprouting potatoes and onions, cabbage, some canned fish—but the scarcity was such a stark contrast to the images of lushness and prerevolutionary life that I’d known through literature. Yet I found that it was over meals (it might have been the vodka) that my wariness dissipated. There was something about communal gathering around the table that enabled entry into another culture, even during the Cold War.

When I started graduate school, I wanted to write my dissertation on food in Russian literature as a marker of social status and nationalism as well as character development. This was Stanford University in the early 1970s. I was basically told that I was not a serious scholar. So I wrote on Nikolai Zabolotsky, a fabulous poet. I’m not sorry I did that. But within two weeks of arriving at Williams College in 1983, a newly minted Stanford PhD, my first book came out, and it was a Russian cookbook.

CC

The perfect way to thumb your nose at the establishment.

DG

Well, my second book was on Zabolotsky, and I kept both tracks of my career going. But things have a beautiful way of converging. When the production company behind the PBS series The Mind of a Chef decided they wanted to do a print publication that would be focused on food preservation—the soon-to-be launched Cured—they got in touch with me. I now realize that the time I spent in the Soviet Union and Scandinavia, where the seasons change dramatically and winter reserves are essential, has informed my understanding of the exigency of preservation. Though I would say that now, at least in the United States, preservation techniques are more about deliciousness than survival.

CC

In fact, there seems to be a reverse socioeconomic relationship between the role of preservation in the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s and its popularity in the United States right now. Preservation, for many of us, has become a trendy, leisure-time activity—a hobby.

DG

It is. There are so many hipster DIY preservationists—I shouldn’t call them preservationists, but fermenters and picklers. When I was asked to be editor of Cured, I thought: If only I could grow a beard, or at least adorn myself with tattoos, then I’d look like the type to edit this magazine! One of my aims with Cured is to make this generation aware that there is a long history of food preservation. I think that once they begin to understand the different cultural traditions—because we are looking at these techniques globally—what they’re doing themselves can become all the richer.

CC

You mentioned the Soviet Union and Scandinavia. I am curious whether you have found a link between climate and canning.

DG

Well, I thought that I had until I started delving deep into these practices throughout the world. I began with the places that I’m most familiar with, the cold places where you have to make sure that you dry or pickle or brine or otherwise preserve produce so that you can get through a long winter. Then I considered the very hot, humid climates, like Southeast Asia, where they’ve been fermenting fish sauce forever.

In ancient Rome, where it was also quite hot, they were taking little anchovies and allowing them to ferment, making a sauce that is similar to what we know as Worcestershire sauce. And in Polynesia, they ferment breadfruit not only because it extends the shelf life of the fruit, but because they like the taste.

In most societies, before food became as globalized as it is today, there was always a staple. Rice or cassava or maize—some kind of starch—something bland. Something that tastes good enough but lacks pizzazz.

Anthropologist Sidney Mintz helped develop the core-fringe-legume hypothesis, which suggests that many cultures have a neutral core food with more pronounced fringe foods around it. This phenomenon isn’t climate dependent or a consequence of preserving, and yet a lot of the fringe foods turn out to be cured, fermented, or pickled. Their flavors have been intensified, adding excitement and nutrients to what would otherwise be a monotonous diet. Think about kimchi. When you have rice with kimchi, it zings.

CC

I had thought of preservation or pickling or salting as driven solely by necessity. You’re saying that necessity is only part of the story, but that it’s also, or equally, related to a desire for flavor.

DG

That’s what I like to believe.

CC

But I do still wonder whether a culture develops a taste for strong-tasting foods out of necessity first, or whether there is some innate desire for strong flavors. It’s a chicken/egg or, better, chicken/pickled egg question.

DG

Or a thousand-year-old egg.

CC

Exactly.

DG

Preservation stems from necessity. But if the foods weren’t delicious, then people wouldn’t continue to consume them. Unless they really did need to eat for survival, the undesirable food would still be in the larder come spring. There’s so much labor and skill involved that preservation can no longer be seen as the sole motivation for these foods’ continuing place in the diets of so many cultures around the world. Even if preservation’s genesis is linked to necessity, the act became an art, or at least a highly refined practice.

CC

I want to go back to the Soviet context and think about how space figured within the preservation equation. Storage of food and objects of daily use was particularly fraught, especially for urban apartment dwellers. I’m thinking of early Soviet “living cells”—the tiny sleeping rooms in communal housing projects designed to accommodate the reproduction of the workforce solely. Food was to be supplied by the factory kitchen and eaten in the canteen; books were to be accessed and read in the common reading room; clothes were to cycle in and out of the public laundry. In drawings of these living cells there is almost no storage—a logical architectural response to total communal provisioning. Few of those projects were actually built, but of course the kommunalka, or communal apartment, was a spatial blight of Soviet life right until the end. Where was food stored in communal living arrangements?

DG

The architects of those early projects were overwhelmingly male, correct?

CC

Oh, absolutely. Yes.

DG

They didn’t think about storage needs because they weren’t the ones having to deal with bed linens, or pots and pans, or preserves. Their needs were met by mothers or wives, and so they didn’t stop to consider the domestic basics.

CC

Of course, in these largely theoretical communal housing designs, the whole point was to do away with domesticity. There were a few female architects; it would be interesting to look at whether their competition entries for communal housing treated storage differently.

DG

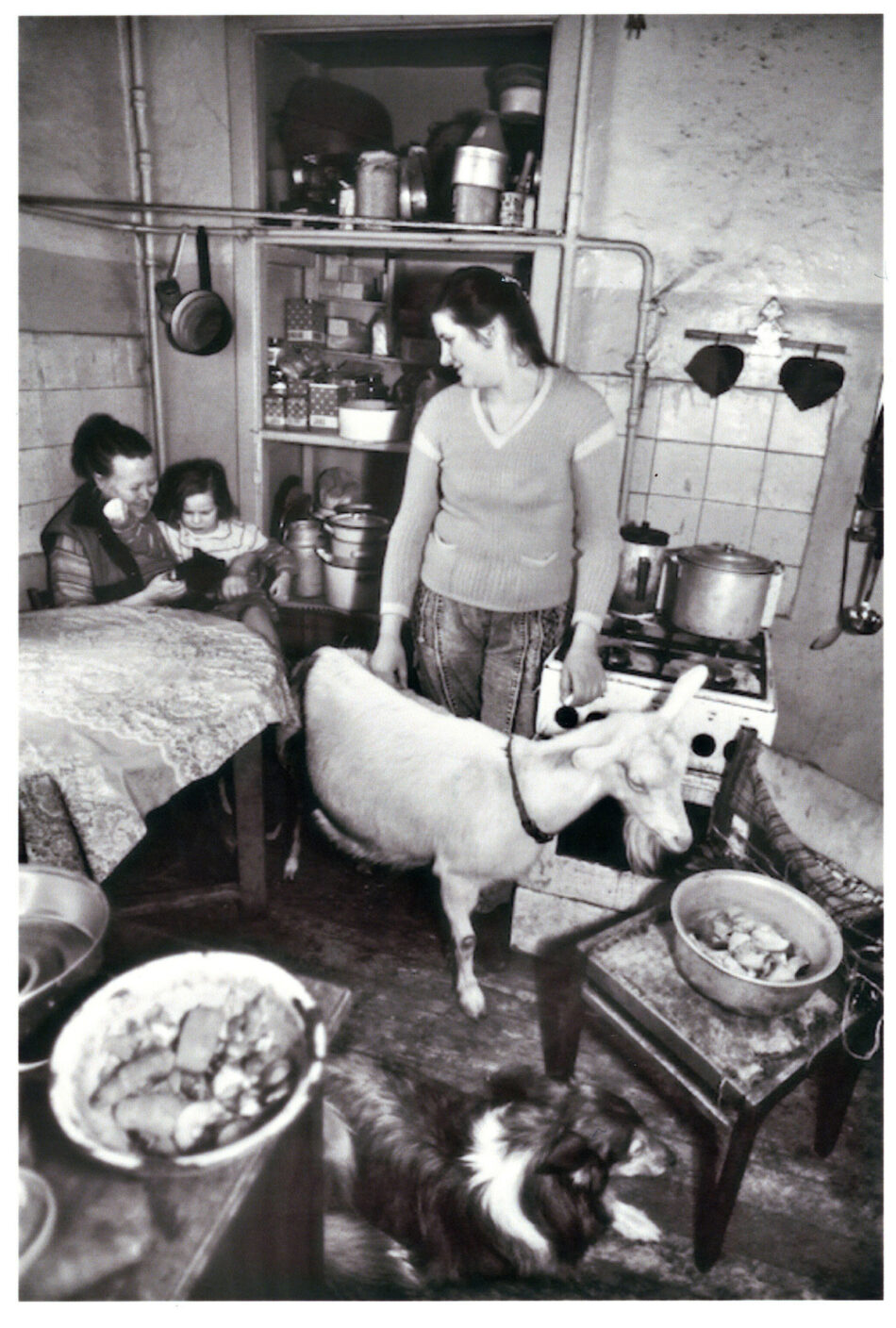

But kommunalki were different from the communal living models that sprung up in the West in the 1960s and 1970s, which were filled with like-minded people. In the West, everyone in these communities lived together, grew their own food, and took turns making huge pots of soup and baking loaves of whole-grain bread. They shared an ideal; their living arrangements were a lifestyle, by definition voluntary.

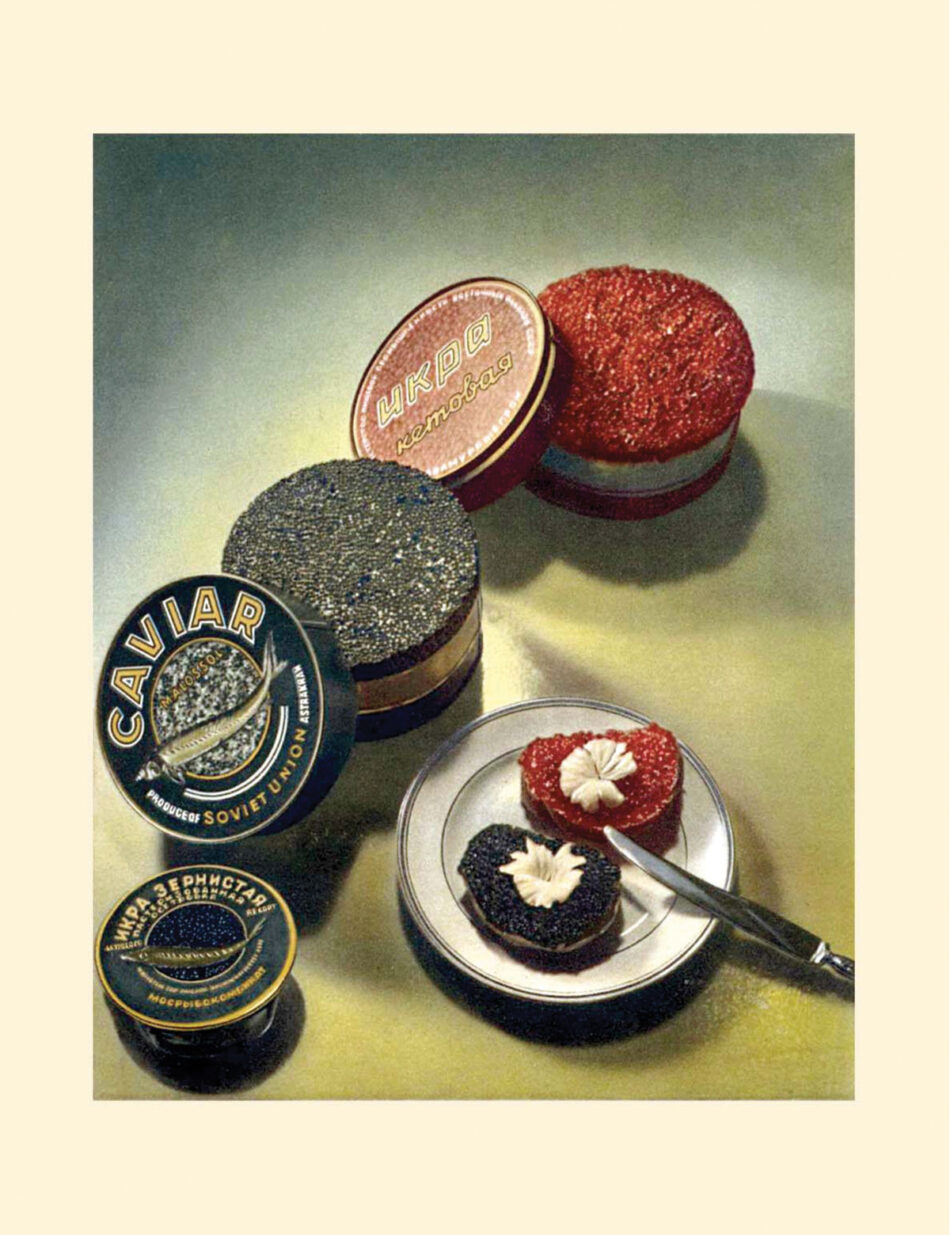

In the Soviet communal apartment, a person had no choice as to who the 10 or 12 neighbors living in adjacent single rooms would be. There were lots and lots of battles. There was also theft, because the only “private space” was the bedroom-cum-living room. There were long common corridors where coats, boots, and cross-country skis were stored. Then, there was the communal kitchen, which had multiple stoves. People kept their pots and pans there—they were banged-up aluminum, not anything that people worried about losing. Their preserves were more precious, so they were never kept in the public space.

Every room had a window and usually some sort of exterior space—if not a balcony, a wide sill. For much of the year, food could be stored on that sill. But the best place of all was under the bed. It’s telling that when refrigerators were introduced into the communal apartments in the 1960s, they went into the bedrooms, not into the shared spaces.

One of the most extraordinary meals of my life was in Moscow. It was during the late Soviet period, around 1985, and I had met this guy at a party. He was a cardiologist, and he invited me to come to dinner. I assumed that he was going to be living in some luxurious place, but he was a bachelor and he lived in a communal apartment. Even though he was one of the most renowned heart surgeons in the country.

CC

That’s phenomenal.

DG

He sat me down in his little 12-by-12 room. It was wintertime, so he reached out through the double-paned windows to get the bottle of vodka. He took two shot glasses from the shkaf, or wardrobe, and then reached under the bed. This was the amazing moment for me. Out came a gallon jar of belye griby, porcini. He said, “These are my own.” He had gathered them. He had salted them. He kept them under his bed. It was the most beautiful and most deeply Russian experience.

CC

By his saying, “These are my own,” all of a sudden you can imagine him walking through the forest. There must have been an immediate understanding—a telescoping— of what it took, both in terms of geography and temporality, for those mushrooms to end up under that bed.

DG

Under the bed is a dark, cool place, so in terms of storage protocol, it’s great.

CC

You mentioned the shkaf—the enormous glass-fronted wardrobe that typically took up a whole wall in the main room of the Soviet apartment.

DG

It was an object of fetish.

CC

It seemed to me a storage solution specific to the Soviet period, but I’ve been disproven, because it’s a persistent piece of furniture in Russia today, and the cultural habit of putting everything that’s of importance to a family in this wardrobe also persists. Is this kind of public storage display something that predates the Soviet period?

DG

Well, it had its cultural moment in the Soviet period, when there was so much material deprivation. If people had some beautiful pieces of cut crystal or nice porcelain—anything that glinted—along with treasured volumes of poetry, they would be kept in the shkaf.

It is a Soviet iteration of something that goes way back, not just in Russia, but in Europe. In medieval England, precious objects—decanters, gold plates, silver—were displayed on the sideboard, which was originally a tiered stand. When porcelain came into fashion in the 18th century you started seeing it on sideboards too. There are a lot of paintings that portray this tableau. If you look at Botticelli’s Wedding Feast from 1483, right in the foreground is an enormous sideboard. This is a feast en plein air, but the sideboard is set up to show the wealth of the host.

I see the shkaf as a continuation of the need to display one’s material worth, one’s status. Displayed yet contained. I always looked first at what books people kept in the shkaf, which told me in an instant if it was an intellectual family. And I gained a deeper understanding of the antics of Zabolotsky and his fellow OBERIU poets, who would materialize their slogan of “Art as a Cupboard” by hauling an actual cupboard onto the stage to demonstrate the inseparability of art and daily life.

CC

The percentage of poetry versus translations of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

DG

Exactly.

CC

One of your most remarkable scholarly pieces describes women’s food provisioning efforts over the course of the 900-day siege of Leningrad from 1941 to 1945. Has that research heightened your awareness of how women provide for their families during war, no matter the geography or time?

DG

There’s a really beautiful essay that Alma Marin wrote for Gastronomica in 2005 called “The Unbearable Lightness of Wartime Cuisine.” It’s about Sarajevo in 1993. She’s a journalist and a writer, so she was from the intelligentsia and enjoyed high socioeconomic status before the war. She describes what she had to go through to get food and to feed her children, but also her efforts to keep joyousness alive when they were surrounded by nothing but despair. There’s also a recent little book called Jam Session (2014). It was part of a fundraiser for the Parents Circle, a group of Israelis and Palestinians who had lost family members in all the years of fighting. It’s a collection of portraits of the survivors, using preserves as the metaphor. They’re preserving the memories of those who died—but also, the recipes themselves preserve their cultures.

CC

A final, non-food-related question. Like you, I have spent a lot of time in Soviet-era archives, and have been struck by the amount of paper—official documentation in duplicate—that was preserved. Do you think that there is a relationship between the everyday material deprivation that we’ve discussed in that culture and excessive textual stockpiling?

DG

In fact, during certain parts of the Soviet era there wasn’t enough pulp to make paper. The paper became worse and worse in quality, but they still preserved it. Do you know Lev Kopelev’s book To Be Preserved Forever (1977)? He was a dissident, a friend of Solzhenitsyn. A lot of the documents relating to the Gulag system were stamped with the phrase khranit’ vechno—”to be preserved forever.” It’s really a basic human urge, a kind of hedge against oblivion. We have this need to make our mark and ensure that what we’re doing doesn’t wither away like . . . Wait, is it the state that will wither away?

CC

Yes. Exactly.

DG

This impulse was overlaid by a bureaucracy that you can already read about in Gogol. All his chinovniki, little bureaucrats, are creating endless trails of paper. The system perpetuates itself.

CC

Even if it’s not specific to the Soviets, their system of archiving was actually quite remarkable. The archives are difficult to navigate, and the Russians make it difficult for people to access them.

DG

But they’re there. They persist, for as long as the paper lasts.

Darra Goldstein is the Willcox B. and Harriet M. Adsit Professor of Russian at Williams College and founding editor of Gastronomica. She served as editor in chief for The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets (2015) and has authored five cookbooks, including The Georgian Feast (1993) and Fire + Ice: Classic Nordic Cooking (2015). She is editor in chief of the new magazine Cured.

Christina E. Crawford is assistant professor of architectural history at Emory University. Her research explores design strategies particular to transitional periods. She is currently writing a book about early Soviet urban theory and practice.