South Side Land Narratives: The Lost Histories and Hidden Joys of Black Chicago

Publicly expressing Black pain can render reactions of solidarity, healing, and empowerment, or exhaustion, guilt, and helplessness. However, Black voice can be a powerful instrument of change—used as a currency to be saved or spent or as a carrier of demand and solution. The past year has unearthed untold knowledge that gives additional context to the root of what drives this voice—its trauma, its demands, and its joy. Making this knowledge more public can help to inform how we understand and engage one another; how we reframe harmful Black narratives that shape the public perception; and how the power of Black creativity and resiliency as a political device can produce spaces of Black-centered freedom and liberation.

This essay and the corresponding collages aim to represent and make public the confrontation of pain and quest for joy found in the Black public realm of Chicago’s Mid-South Side. Each collage illustrates the relationship between publicness for Black Americans and the current urban landscape of vacancy including southern migration in response to public denial; the public scars left by urban renewal’s land mutilation; and the relentless pursuit of public freedoms in the public realm. The series offers a reflection on the contests that exist over land, space, and place alongside the aspiration of Black Americans to simply occupy and be carefree in public, unencumbered by fear and liberated from self-consciousness.

The collages include present-day mapping, photography, and historic images, in combination with clippings from, and references to, the imagery and symbols of Chicago’s Black life and prosperity used in the work of notable African American artists. My objective was to create new portrayals of the South Side and its people by making public some of the lesser-known narratives about these neighborhoods over the last century.

The narratives, rooted in the ownership and occupancy of land, reveal the practices of institutional racism, exclusion, and extraction, juxtaposed against images of the undiminished spirit, ambition, productivity, and creativity of Black Chicagoans. Richard Wright describes this as the “extremes of possibility” in his introduction to Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, the seminal 1945 book by University of Chicago researchers St. Claire Drake and Horace A. Cayton on Negro life in Chicago: “There is an open and raw beauty about the city that seems either to kill or endow one with the spirit of life. I felt those extremes of possibility, death and hope, while I lived half hungry and afraid in a city to which I had fled with the dumb yearning to write, to tell my story.”1

BLACK MIGRATION | PUBLIC DENIAL

AVAILABLE WITHOUT FREEDOM | In the introduction to Black Metropolis, Richard Wright describes white Chicagoans questioning why Black migrants willingly uprooted themselves from the South, given the racial animosity and rapidly deteriorating built environment of Chicago’s South Side in the early 1900s. Between 1916 and 1970, six million African Americans migrated from the rural South to industrial cities in the Midwest and Northeast. In the first five years of the migration, Chicago saw a 50 percent increase in the Black population—from 46,000 to over 83,000 residents; by 1937, more than 237,100 Black Americans called the South Side home.2

Fleeing the Jim Crow South meant the possibility of industrial rather than agricultural work, with the promise of better wages and greater public freedoms to move about the city. Upon arrival however, migrant Blacks were confronted by a different form of public denial. Throughout the Jim Crow era, when separate but equal was the law of the South, northern cities maintained a different form of discriminatory practices perpetuated by white homeowners, real estate agents, lenders, and employers. Racial restrictive property covenants, redlining, and blockbusting formed an impenetrable barrier, intentionally constraining the geographic and economic mobility of Blacks in the city. These practices simultaneously and systematically devalued Black land assets and deepened the narratives of Black inferiority and Black neighborhood undesirability. The new Black Chicagoans found themselves spatially confined to an area that would become the Chicago Black Belt, unable to avail themselves of all the offerings of urban life.

Today, the Black Belt is simply referred to as the South Side. For a Black Chicagoan, growing up on the South Side is to be nourished in Black space, but often with little knowledge of the forced restriction that once bound people together in place. Nonetheless, the South Side now proudly belongs to Black Chicagoans, and their claim is validated by its history of confinement.

AN UNGUARANTEED EXISTENCE incorporates the three Great Migration routes used by Black Americans to access the greater personal freedoms and fortunes promised by cities outside of the southern states. The routes are intertwined with thorny cotton stalks representing the escape from chattel slavery and journey toward the Chicago Black Belt. Underneath is a 2020 aerial map of the Washington Park and Woodlawn neighborhoods, where over 200 acres of publicly owned vacant land appear as green voids on the map similar to the formal park spaces of the neighborhood. These vacant lands, the byproduct of urban renewal, disinvestment, and Black population exodus from the South Side, are demanding a new form of land care by remaining residents. Today, however, tending the land is not generating wealth for anyone; instead it is a temporary investment of sweat equity to cultivate greater safety, beauty, and mental well-being while residents wait for redevelopment.

PUBLIC CONFINEMENT | BLACK METROPOLIS

“But the American Negro, child of the culture that crushes him, wants to be free in a way that white men are free; for him to wish otherwise would be unnatural, unthinkable.” Richard Wright

AVAILABILITY REALIZED | By the 1940s, despite the racial restrictions enforced on the South Side, Chicago’s Black Belt neighborhoods—becoming known at the time as Black Metropolis—were becoming a land of promise, prosperity, and a blueprint for Black urban culture. The concentration of unemployed labor after the Great Depression, persistent racial segregation, and other forms of discrimination created a community that demonstrated the self-reliance and creative production that have long served Black Americans in times of austerity and deprivation. The denial of access to the city at large activated the necessity of Black-created and -controlled commerce, finance, media, and entertainment that would become visible to—and ultimately consumed by—the very citizens who deemed Black people and places unworthy.

Drake and Cayton’s Black Metropolis establishes that at the tail end of the Great Migration, the Black Belt had over 2,600 Black-owned businesses, accounting for nearly 50 percent of all businesses in the area, and with access to a Black purchasing power of nearly $150 million. Their research also elaborates on the existence and role of Black influence and wealth through the church, media, and entrepreneurship: “To the Negro community, a business is more than a mere enterprise to make profit for the owner. From the standpoint of both the customer and the owner it becomes a symbol of racial progress, for better or for worse.”3 But after the Second World War, the physical spaces built by these Black cultural producers would become lost to urban decline and denied access to the federal aid that was afforded to white homebuyers in the new frontier of the American suburbs.

The relatively short-lived prosperity born in Black Metropolis creates a gap in our understanding of the generative ingenuity propelled by Black Chicagoans. In Selling the Race, Adam Green describes this gap in knowledge as an underappreciation of Black-led production “where expansive imagination is often counted as a luxury, or distraction from the harsh realities of proscription. Consequently, urban blacks have generally been seen as history’s victims, rather than its makers. This has exacted a steep cost on our overall knowledge and perspective, for it obscures African Americans’ central role in fashioning the world all of us live in today.”4 The stories of Black imagination and production are rarely incorporated into our public knowledge of American ingenuity and invention. The knowledge of the existence of Black prosperity, amassed only a few decades after Emancipation, must become a more visible public truth within the canon of American histories.

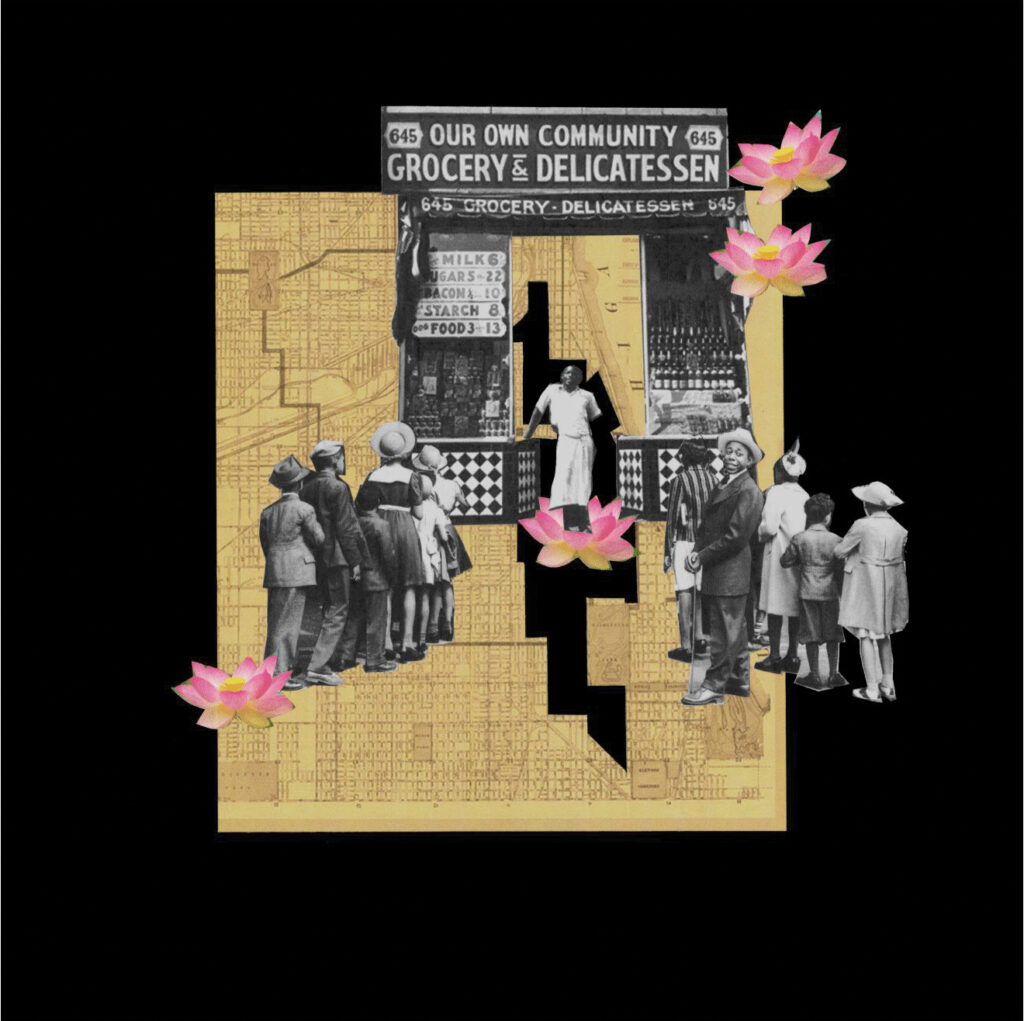

WE USED TO BALL uses a 1906 map outlining the boundaries of Chicago’s Black Belt against images of Black-owned businesses to remind us that Black Americans have always had the capacity to generate wealth, even just one generation removed from slavery. Black Metropolis, despite its spatial confinement within racially restricted boundaries, was a prosperous economic center, self-sufficiently sustained by the recirculation of its own dollars by its own people. It is unlikely that today’s generation of young Black residents have any knowledge of the economic and cultural power this place once held because the current ruinscape holds no visible memory of wealth, which is symbolized here by the lotus flower.

PUBLIC SPACE | BLACK RIGHTS

“Violence was a common reaction to any encroachment.” John Keilman

DEMANDING AVAILABILITY | Chicago’s public amenities have a long history of being contested spaces of exclusion. Until the 1960s, Lake Michigan’s public beaches were controlled through white intimidation, discouraging Blacks from exercising their rights to public access. To disrupt this practice, Black and white activists organized beach “wade-ins”—protest events where people formed long human chains and marched onto the beaches and into the lake. In a 2011 Chicago Tribune article, John Keilman interviews Nicholas Juravich, a University of Chicago research student studying the wade-ins, who says, “Many whites considered the lakefront their preserve. The presence of blacks offended their sense of social order. . . and the notion of young, half-dressed blacks and whites mingling on the shore raised fears of race mixing.”5

Keilman’s article goes on to describe how Black Chicagoans, despite their community status, were routinely intimidated: “In 1960, not even a black cop was safe at Rainbow Beach. Patrolman Harold Carr took his family and friends there on a steamy July afternoon and was summarily mobbed by a gang of rock-throwing white hooligans. ‘Why do you come down here?’ they jeered, according to a story in the Chicago Defender. ‘Can’t you feel that you’re not wanted?’”6 The wade-ins were a peaceful disruption of the fear-driven supremacy by white beachgoers. Today, Rainbow Beach, situated at the eastern edge of Jackson Park, is a favorite of Black Chicagoans, but its history as a contested space is little known except for the markers installed and dedicated in 2011 to commemorate the wade-ins.

Five years ago, a new contest over the right to occupy public space emerged. By 2025, the Obama Presidential Center will open as a new building in Jackson Park. The siting of the center in the historic Frederick Law Olmsted park has been controversial, again raising questions of acceptance, access, and belonging, but this time for a building, not a people. Since 2016, when the Obamas chose to locate the center in their hometown, a long and vocal public battle has been underway regarding the appropriateness of the building, its scale, and use on public park land, challenging the notion of what is public and for whom.

Critics—mostly people from outside the surrounding neighborhoods—have opposed the new building, public plaza, and associated roadway reconfigurations. They point to Olmsted’s 1894 vision for Jackson Park: “All other buildings and structures to be within the park boundaries are to be placed and planned exclusively with a view to advancing the ruling purpose of the park. They are to be auxiliary to and subordinate to the scenery of the park.”7 Meanwhile, the predominately Black residents of the surrounding communities have generally embraced having a center devoted to the Obamas on the South Side, as they are hopeful it will bring much-needed attention and equitable reinvestment back to the former Black Belt. However, it is also important to note that this enthusiasm is coupled with fears of displacement if investments are not directed to local Black households, businesses, and institutions.

These dialogues about the center force the question of who and what has the right to occupy public space, whose interests are prioritized, and who gets to decide. While the arguments over the siting of the Presidential Center have not explicitly been race-based, the optics around who is advocating for the outcomes that directly affect those who will experience the greatest impact (good or bad) is situated in a racial climate common in a racially segregated city. As such, the act of claiming access to public space and who gets to determine the cultural and economic value of Black occupation must always be understood as the pursuit of Black rights.

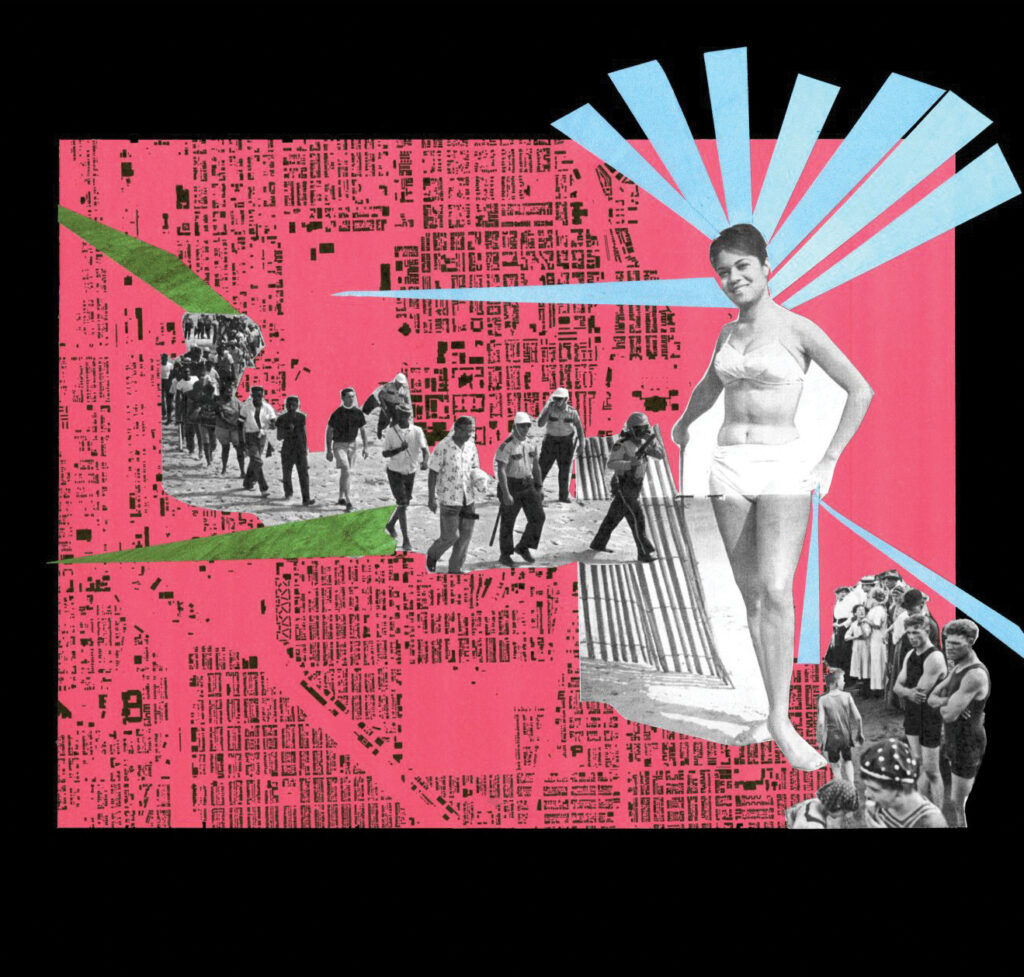

MY BEAUTY WILL NOT BE DENIED is a reminder of how little we know about the origins of some of our most beloved Black spaces. During the wade-ins, a human chain of people moving across the city was required to bring about racial justice and access to a public space. During this same time, John H. Johnson, owner of Johnson Publishing company, was publishing Jet, a weekly news magazine celebrating urban Black modernity. The centerfold beauty was often a local Chicago woman posed somewhere along the very beachfronts white Chicagoans were refusing to share. In this context, the centerfold photo represents both the mundane day at the beach and the fantastic fighting for the right to the beach. The question of who and what belongs in the public realm is nonexistent for those whose rights are an unquestionable birthright, but for others who are still waiting for the equal fulfillment of rights, access is a constant contest. Nonetheless, the blue streams of water/sky, taken from Amy Sherald’s Michelle Obama portrait represent the resistance to denial, the optimism for ultimate equality, and the beauty and strength of the Black woman.

PUBLIC SCARS | BLACK MUTILATION

AVAILABILITY TAKEN | The public policies that systematically perpetuated urban removal, redevelopment, and planned shrinkage are being redefined as a form of racial capitalism—the extraction of value from the racial identity of others.8 Those policies left a landscape of urban ruin in the former Black Belt neighborhoods of Chicago. Fallow for decades, these lands, both privately and publicly owned, have been waiting for external capital interests to reestablish economic value. Meanwhile, generations of Black Chicagoans have lived in a state of perpetual disinvestment with high percentages of concentrated poverty, poor health, and low employment prospects.

Writer and activist Lucy Lippard is quoted as observing, “Poverty is a great preserver of history,” noting that it is within communities of disinvestment that we confront how economies dictate what does and does not happen to land.9 However, the vacancy we observe in low-income Black neighborhoods does not tell a complete story about the contentious causes of decay. Instead, mainstream media conditions us to read this landscape as a reflection of the neglect and disregard of Black people to care for and invest in the places where they live, thereby placing blame on the poor for their inability to pull themselves up by their bootstraps—a quintessential American narrative. But in Storming the Gates of Paradise: Landscapes for Politics, Rebecca Solnit reminds us that “the great ruins have been situated on what is first of all, real estate, not sacred ground or historical site; and real estate is constantly turned over for profit, whereas a ruin is a site that has fallen out of the financial dealings of a city…”10

On Chicago’s South Side, falling out of financial dealing meant the demolition of physically deteriorating buildings and the consolidation of poverty within mile-long superblocks of public housing. By the late 1940s, the housing stock of Black Belt neighborhoods was crumbling due to resident overcrowding, landlord neglect, and white flight. What was once the center of Black economic prosperity was swiftly becoming the South Side slum. The Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954, in combination with the Federal Highway Act of 1956, created a suite of federal programs that helped support state and city governments in their efforts for “urban renewal” in predominantly Black neighborhoods, leading James Baldwin to coin the phrase “urban renewal is Negro removal.” These programs were focused on slum clearance in order to make way for new economic development, affordable housing, and urban infrastructure projects. Instead, these public actions led to the concentration of poverty for generations of families, in part because private capital—in the form of commercial and residential amenities—did not follow these public investments. It followed the white Chicagoans fleeing to the surrounding suburbs, who were supported by other federal home loan subsidies provided by the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, or Freddie Mac.

Between 1955 and 1966, urban renewal projects displaced more than 300,000 people of color nationwide, according to the Renewing Inequality Project developed by the University of Richmond’s Digital Scholarship Lab. While Black Americans were just 13 percent of the total population in 1960, they comprised at least 55 percent of those displaced. Many Black communities were also fragmented or razed to make way for new infrastructure projects.11 Today, the highways of the South Side, constructed in the 1960s, together with the lands left undeveloped after urban renewal erasure, remain as visible scars of the land mutilation and the social and economic harm imposed on the former Black Belt communities.

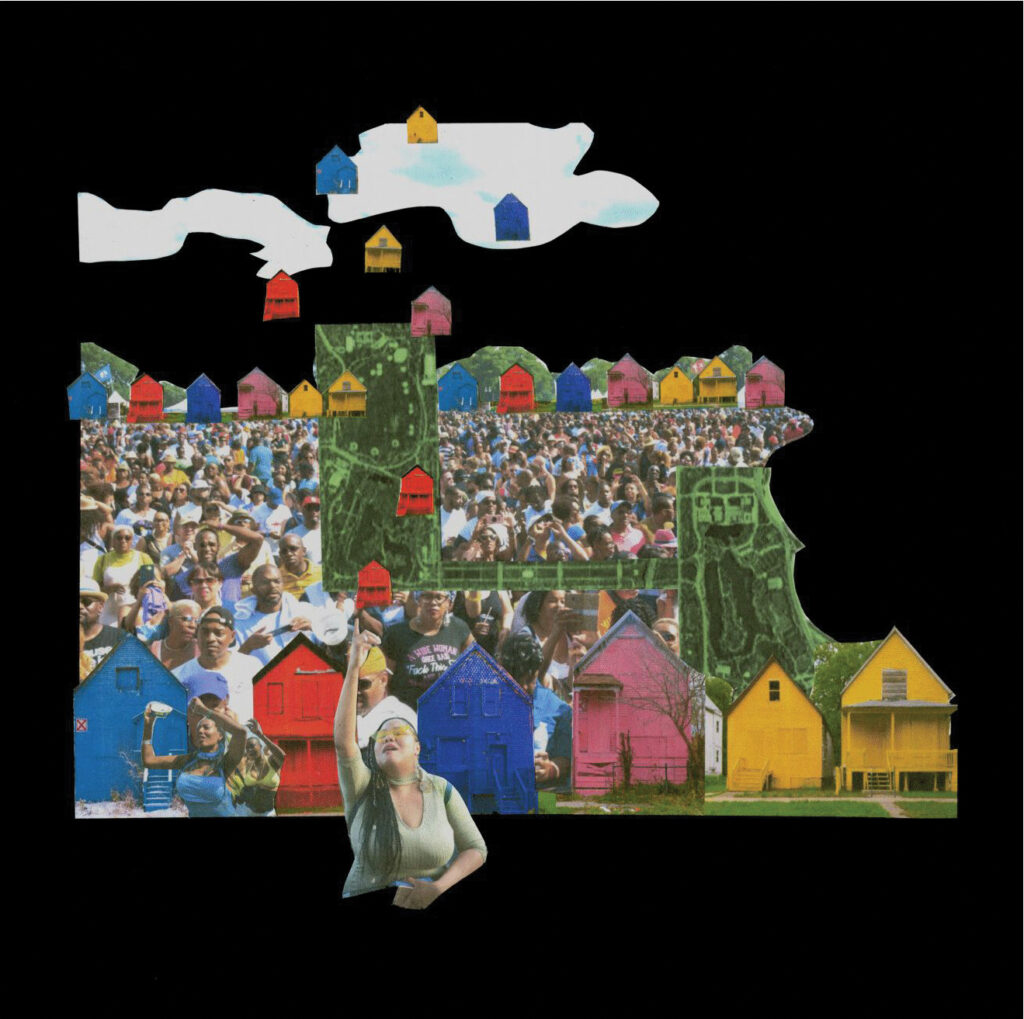

. . .HOUSE WILL LIFT ME UP celebrates the origins of house music in Chicago and the legendary Chosen Few Old Skool Picnic. Started 40 years ago by a few house DJs in the tradition of the Black family barbecue in a public park, this casual communal gathering has exploded into the appropriation of Jackson Park by 40,000 souls every July. The sounds and beats of house music can be transporting—if you let it take over—freeing your body and soul from the mutilated lands surrounding the park, and into a space of joyful escape. Amada Williams’s Color(ed) Theory houses, cloaked in the palette of Black commercial products, are used to represent the artifacts and trauma of real estate violence. But the collage situates the painful image of these houses against the joys of house music and its consumers, known as “house heads.” Black joy can always be found in Black spaces, where urban sanctuaries are often created within the context of urban ruin. By acknowledging the trauma endured by disinvestment, the picnic and its music create a haven within marginalized space for marginalized people. House, as sanctuary, can and should counteract the protracted harm inflicted by insufficient resources, amenities, and investments and lift one to a place of safety, care, and freedom of movement. Thus, the Color(ed) Theory houses are lifted up, rising above their current context, and hopefully making way for new sanctuaries of dwelling.

PUBLIC SPACE | BLACK SPACE

I’m hoping to see the day

When my people

Can all relate

We must stop fighting

To achieve the peace

That was torn in our country

We shall all be free

Follow me

Why don’t you follow me

To a place

Where we can be free

“Follow Me – Club Mix” Aly-Us, 199212

AVAILABLE CREATIVITY | Chicago’s Washington Park holds a prominent history of creativity, exhibition, and amusement. Twenty-three years before the first wave of the Great Migration, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition used the South Side—specifically Jackson Park, Washington Park, and the Midway Plaisance—to showcase the technological advances of the time. In 1902, following the success of the exposition, Chicago’s civic-minded business community constructed another space of amusement on South Side park land. The White City Amusement Park was imagined by one of its benefactors, hotel developer Joseph Beifeld, as a space of escapism. He described his ambition to colleagues by saying, “I’m glad of one thing, boys… we will give the people of Chicago an opportunity of enjoying themselves such as they have never yet dreamed of. When I think of the hot stufl’y (sic) theatres in Chicago on summer evenings; when I think of the absolute barrenness of the lives of so many thousands of men, women and children there, who have no place to go for clean, unobjectionable entertainment and pleasure, I’m glad that we are going to build White City, from humanitarian principles if for no other reason.”13

When White City opened, offering arcades, the White City Roller Rink, a beer garden, and a boardwalk, it was surrounded by neighborhoods growing in African American population. In fact, the local Black population grew by more than 250 percent between 1889 and 1905.14 But their admission into the park was barred despite the 1885 Illinois Civil Rights Act which made business discrimination illegal. When the park closed in 1933, the roller rink was the only feature to remain in operation, but it continued to be off-limits to Blacks Chicagoans. In 1946, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), founded four years prior, used the racially restricted rink as an opportunity to focus their desegregation efforts. The group staged public protests and filed a lawsuit with the aim of ending racial discrimination in public and privately controlled spaces. Within a few months, CORE was victorious; the rink was desegregated and renamed Park City Roller Rink until it closed in 1958.15

Today, Washington Park is surrounded by majority African American neighborhoods except for Hyde Park to the east, home to the University of Chicago and its hospital. Current Black or white residents would find it hard to imagine the park was conceived of and operated as exclusively white space. In fact, college students and white residents of Hyde Park are rarely seen east of Cottage Grove Avenue, the park’s eastern border. Black residents, on the other hand, have claimed the park for their own recreation, amusement, and marking territorial rights.

Public open spaces that exist in Black neighborhoods—such as Washington Park—hold the possibility of simply being spaces unencumbered by the kinds of unspoken permissions or questioning of acceptance that Black bodies experience when moving through spaces dominated by whiteness. But there are also times when the claiming of public spaces—whether by gangs, children playing, or Black creatives and place-makers—could be viewed as political and defiant acts against the history of denial. As a result, public open spaces in Black neighborhoods must become the platform for a Black imaginary to produce an adapted landscape, in opposition to historic contexts situated in racist practices, that make visible an aesthetic of equity, inclusion, and future possibility—an aesthetic of Blackness.

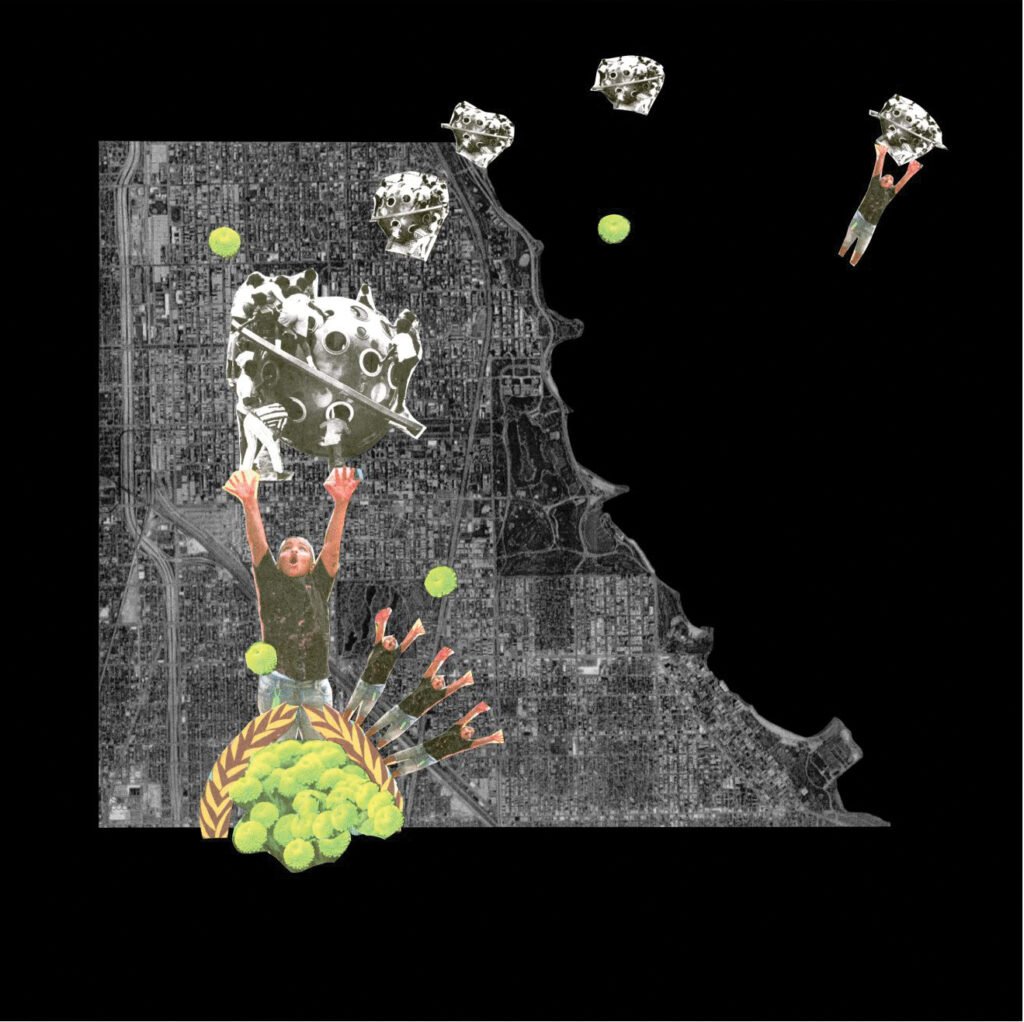

DREAMLIKE IN ITS WILD OUT-OF-PLACENESS centers the joy of a young Black boy in the 1970s at Adventure Playland, a mid-century modernist playground located on Washington Park’s Bynum Island. The playground was designed by Chicago Park District architects and named after Marshall F. Bynum, the first African American member of the Chicago Park District Board, a civic-minded businessman who lived nearby. The park included a spaceship-like sculpture, a zip line, and stackable Lincoln logs. Equipped with supplies, a dedicated art director curated programs that enabled young people to construct alternative futures in contrast to the realities of the adjacent neighborhood’s accelerating physical decline.16 Crossing onto the island was like stepping into an urban utopia. And using healing imagination—akin to what novelist Toni Morrison describes as “dreaming loud,” a power used by one of her characters in Paradise to share, confront, and acknowledge past traumas as a form of healing—was encouraged.17

Vacant neighborhood spaces have the potential to be owned and configured by Black creative imagination—both temporal and permanent—and in doing so, the South Side can be transformed (back) into an economic and cultural Black Metropolis. The dream of what is possible for these lands and the South Side is in the hands and imaginations of future generations of young Chicagoans, but they must be lifted up and supported in their dream-making capabilities. Hence, the young Black boy is placed on the pedestal of chrysanthemums and grape leaves to represent Chicago, achievement, freedom, and a new future for Black Space.

PUBLIC SPACE | BLACK OCCUPATION

“We were unarmed, but we knew that Blackness armed us even though we had no guns.” Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist

AVAILABLE FOR THE TAKING | Public space can be occupied for protest, celebration, or the mundane. The ability of Black Americans to be carefree and at ease within the public realm often requires the appropriation of space through cultural ephemera like performances, festivals, and parades, where Black joy can be claimed without apology, apprehension, or acquiescence. The aspiration is to be at peace in space, unencumbered by unspoken and unseen oppression—a feeling of true liberation. But depending on the identity of the observer, the occupation of Black Americans in public space, outside of those ephemeral events, is often perceived as threatening.

Black bodies in the public realm are not all observed or experienced in the same way. Black girls and women are often rendered invisible in public, overlooked from the checkout line to the sidewalk. Black boys and men, on the other hand, are keenly visible and often confronted, questioned, or challenged about their public occupation. But unlike gender differences, class differences for the Black body are rarely distinguished. In his article “The White Space,” Yale University professor Elijah Anderson notes that “members of the black middle class can be rendered almost invisible by the iconic ghetto. Police officers, taxi drivers, small business owners, and other members of the general public often treat blackness in a person as a ‘master status’ that supersedes their identities as ordinary law-abiding citizens. Depending on the immediate situation, this treatment may be temporary or persistent while powerfully indicating the inherent ambiguity in the anonymous black person’s public status.”18 Anderson’s reference to the “iconic ghetto” represents the stereotype and presumption that the ghetto is where all Black people live, and therefore the burden of disproving this position is placed upon Black people, regardless of income class, before meaningful trust and interactions are possible. Therefore, being armed in Blackness, as Kendi points out, is to have a dogged awareness of one’s position in space, because you never know who’s watching.

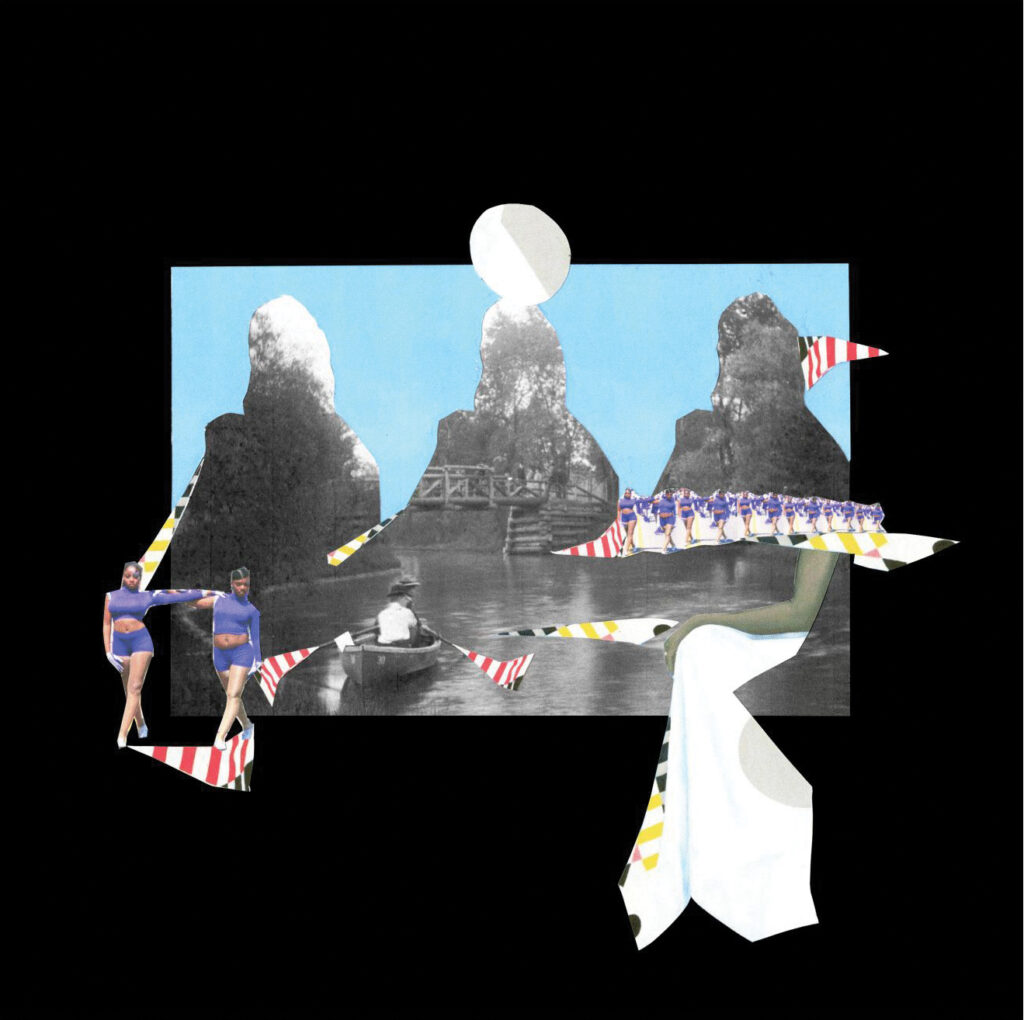

THEY DIDN’T SEE US BUT WE ARE HERE uses a historic photograph of a white couple rowing peacefully in the mere of Washington Park, with white observers standing on a distant rustic bridge. The scene is enveloped by images of feminine power and color. The silhouette of Michelle Obama’s portrait by Amy Sherald forms both sky and forest, while the quilt patterns from the portrait float through the scene as water and terrain. Marching out from the trees are confident young women, arms locked and striding toward the rowers. They are participants in the annual Bud Billiken Parade, founded in 1929 to help fuel the Great Migration, according to the Chicago Defender, the nation’s first Black newspaper. The mission of the parade, named after a fabled guardian of young people, is to celebrate youth, progress, and pride, providing “one of the only spaces where we can openly and emphatically praise the historic roots that plant us into the South Side of Chicago.”19 The female figures throughout the collage are a reminder of the prominence of women in the Black community as heads of households and the fastest growing demographic of entrepreneurs.20 They are emerging from the shadows and excelling to great heights.

PUBLIC LAND | TEMPORARY APPEASEMENT

“…development breeds development, and development breeds stability. Each new owner is an anchor that holds our neighborhood in a safe harbor ahead of the next economic crisis.” “These Black developers are buying back the block,” Crain’s Chicago Business

AVAILABLE ON LOAN | The temporary use of publicly owned land as a means of equitable investment—until it’s deemed worthy of value recapture—keeps these lands in a holding pattern of appeasement. The former Black Belt neighborhoods that surround Washington Park, Jackson Park, and the forthcoming Obama Presidential Center, hold nearly five million square feet of vacant city-owned land. Most of the lands are residentially zoned lots where upper-, middle-, and lower-class Black Metropolis residents once lived.

In 2020, the University of Illinois Chicago Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy published “Between the Great Migration and Growing Exodus: The Future of Black Chicago?,” a study on the city’s Black population shift. It reported that Chicago’s population peaked in 1950, while the percentage of Black residents continued to grow until 1980. But the aftershocks of urban renewal and civic unrest, coupled with the demise of the steel economy in the early 1980s and sustained public and private disinvestment, has triggered a steady exodus of Black people out of these neighborhoods and Chicago over the last four decades. More than 46,000 residents left the Black Metropolis neighborhoods between 1990 and 2016 alone.21

This exodus has opened up new possibilities for land use, ownership, and development. In recent years, temporary murals, community gardens, parklets, art installations, and pop-ups have become the predominate means by which productive community and non-community members have claimed space for cultural expression, identity-making, placekeeping, and commerce. However, access to these lands seldom comes with the right to own or produce generational wealth. Instead, temporary permissions are granted to occupy, beautify, and convene as a practice equity, which means that the engaged may be dispersed, the installed may be deconstructed, and the land may be returned to stasis months—or even days—later.

If true equity—understood as economic and wealth parity rather than community engagement—is the goal, greater attention must be given to the transference of underutilized vacant land into community-controlled ownership as a strategy for Black repopulation and closing the Black wealth gap. According to the Brookings Institution, the net worth of a typical white family in 2016 ($171,000) was nearly 10 times greater than that of a typical Black family ($17,150).22

Harnessing Black creativity to produce wealth is not new to the neighborhoods of Black Metropolis and can be used again to drive demand for development while reanchoring the community in a manner that lessens the vulnerability of displacement. The current creative efforts that prioritize beauty and community participation as a place-saving tactic must now evolve to also become an investment in creative wealth-building that centers on ownership, attracting capital, and monetizing Black cultural production.

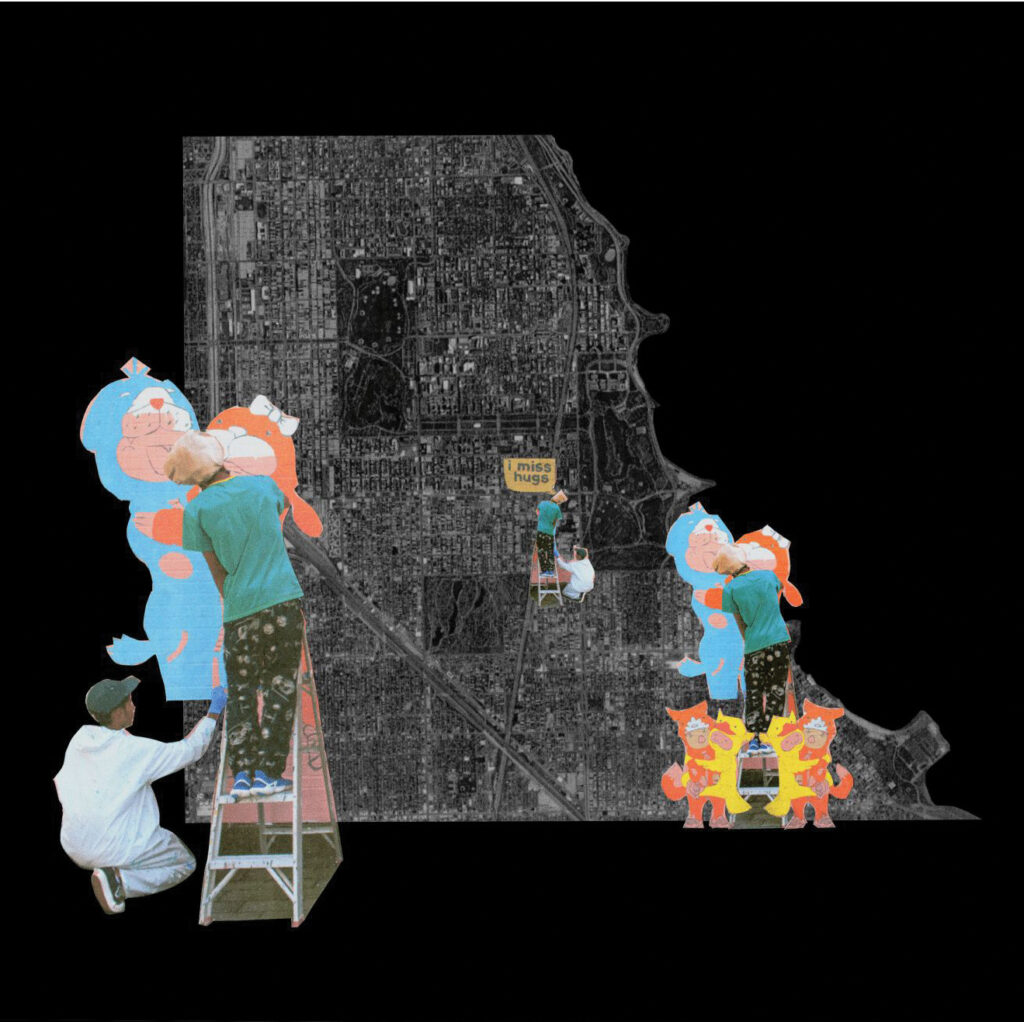

MAKE ART NOT OWNERS speaks to the readiness of public agencies and philanthropic organizations to invest in creative initiatives that promote art-making practices and community engagement as a means of equitable investing in underrepresented communities. These locally produced installations aim to build civic trust, engagement, and social cohesion. They also purport to elevate neighborhood identity, spur economic development, and counteract the threat of cultural displacement often associated with gentrification. Missing from these benefits, however, is the deepening of control and ownership of local economic assets, such as the land upon which these creative endeavors are built. Without land ownership, community residents and businesses remain vulnerable to dislocation. The makers featured in this collage, photographed by Sandra Steinbrecher, work to uplift community and represent a commitment to place, cultural identity, healing, and the value of the aesthetic. Their commitment must now be monetized through an equity stake in the places they work to improve.

PUBLIC WHITEWASHING | BLACK SPACE

“The 1619 Project is a racially divisive and revisionist account of history that threatens the integrity of the Union by denying the true principles on which it was founded.” Saving American History Act of 2020

AVAILABILITY AT RISK | There is a growing fear of American narrative truth telling. In 2021, Congressional Republicans introduced the Saving American History Act of 2020, prohibiting the country’s public schools from using federal funds in the teaching of Nikole Hannah-Jones’s “1619 Project.” The project is a series of essays—published by the New York Times in 2019—that elaborate on the consequences of slavery today, as well as on the impact of African Americans on American life at large. The proposed bill states that “an activist movement is now gaining momentum to deny or obfuscate this history by claiming that America was not founded on the ideals of the Declaration [of Independence] but rather on slavery and oppression.” The proposed legislation goes on to say that “the 1619 Project is a racially divisive and revisionist account of history that threatens the integrity of the Union by denying the true principles on which it was founded.”23 Lawmakers in Texas and Alabama are also debating which version of American history should be publicly offered. These contests over American storytelling expose our current reckoning with who gets to tell our history and who legitimizes its truth.

The whitewashing of the Black experience through narrative is extensive and its practice not only eliminates the contributions of Black Americans, but also minimizes their legitimacy and worth by pathologizing their pain and resistance. In 2020, Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain published Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019, a collection of histories told by African American authors, curated to fill in the gaps of the Black experience in America. In the built environment, whitewashing is most visible when underinvested Black spaces begin to see reinvestment and improvement by people or institutions who are not Black or Black-led. This form of gentrification is experienced by longtime residents as the modern-day version of land taking, “negro removal,” and cultural erasure.

Gentrification is feared, whether it forces residents and businesses to involuntarily relocate or not, and it is almost always objected to by those who are most vulnerable to urban change and most traumatized by previous urban interventions that caused dislocation. As poverty is erased, so too is their history, culture, and a community of shared values and endurance. The long trajectory of land occupation on Chicago’s South Side and its racial narratives are at risk of being obliterated when the opportunity to recapture land value is again available. This reclamation benefits directly from the devaluation of Black real estate assets, and dismissal of the power of the Black cultural aesthetic and prosaic activities of Black life. What is at stake is the loss of control of a neighborhood’s land and landscape—its “Black gold.”

In order to protect these assets from those who wish to acquire and appropriate them without regard for their significance, there must first be a financial and cultural reconciliation of value. Artist and urban planner Theaster Gates understands this mission. His practice of acquisition, archiving, and placekeeping is “deeply invested in the material preservation of neglected social and cultural histories,”24 according to a description of his work from a recent gallery show in Chicago. His practice, and that of Chicago artist Amanda Williams, aims to elevate the inherent value of the everyday urbanism of Black Chicago, in much the same way that musical artists Common and Chance the Rapper have done in their lyrical homages to the South Side. Their art and music are now consumed by art curators and suburban teens, because to consume Black culture is, after all, to be cool, to be progressive, to be woke.

Since the 2016 announcement of the Obama Presidential Center in Jackson Park, land speculation has accelerated on the South Side, increasing the price of land and sparking fears of displacement by current residents. The preservation of cultural heritage through the placement of ethno-representations into new development cannot be the only strategy for withstanding the threats of whitewashing. Black participation in the ownership and development of the future of the South Side must become a primary strategy to ensure that a Black cultural aesthetic remains visible and enduring.

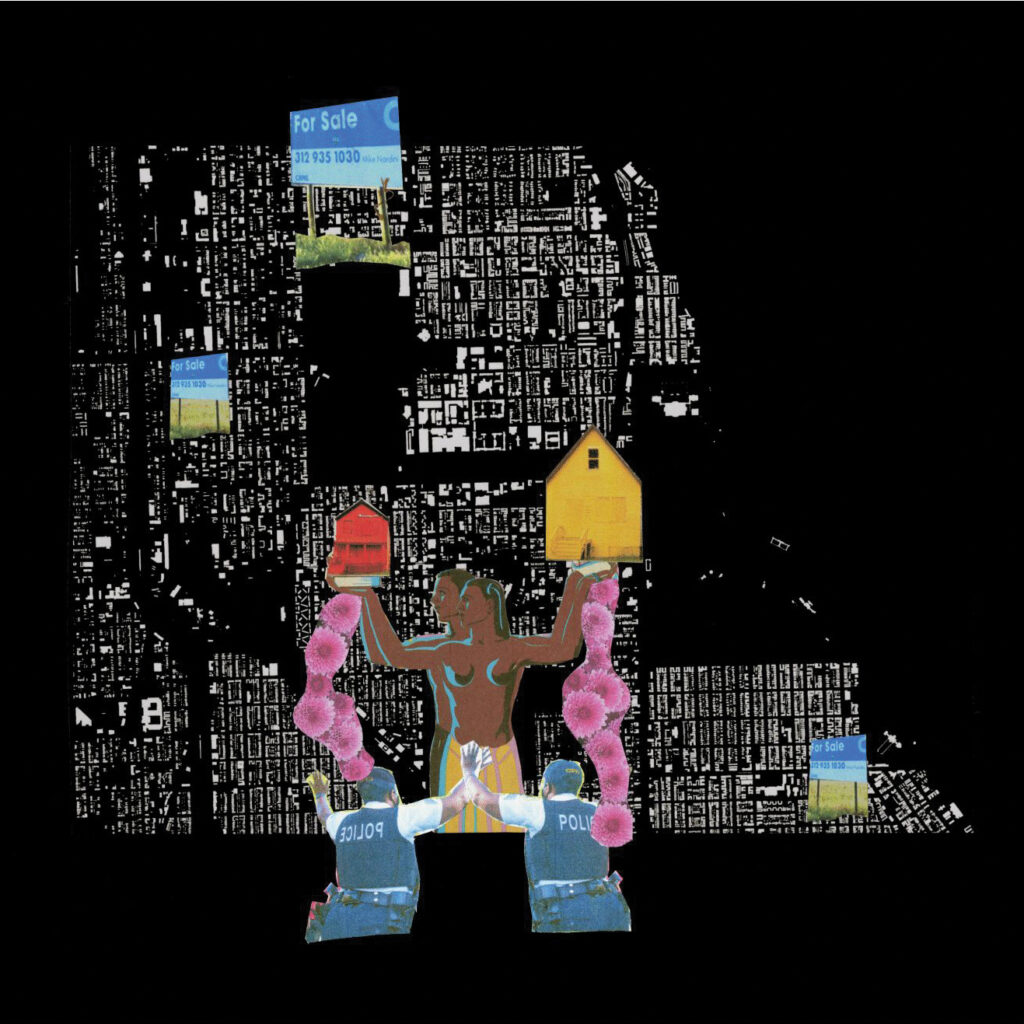

. . .SOUTH SIDE GOLD RUSH represents the threat of gentrification and displacement in the disinvested neighborhoods of Chicago’s South Side. Publicly owned vacant land in neighborhoods on the threshold of change is commonly offered for sale or ground lease through public request for proposals (RFPs), a competitive bidding process for public land dispositions. Referencing imagery from the 1940 American Negro Exhibition, the Black god and goddess lift up the neighborhood’s abandoned land assets as a symbol of public offering. The exhibition, also known as the Black World’s Fair, was curated in response to racial discrimination during Chicago’s 1933 Century of Progress Exposition and was designed to showcase Black excellence in business, arts, and production. Again, Amanda Williams’s Color(ed) Theory houses are used to represent the area’s devalued vacant properties as South Side’s Black gold. The Black police officers represent the community’s desire to fend off and protect these assets from the rush of white investors and instead, seek capital that intentionally puts South Side public land assets in the hands of the Black families who have endured generations of urban neglect.

PUBLIC LAND | BLACK REPARATIONS

O, let America be America again—

The land that never has been yet—

And yet must be—the land where

every man is free.

The land that’s mine—the poor man’s,

Indian’s, Negro’s, ME—

Langston Hughes, Let America Be America Again”25

AVAILABILITY OWNED | In 1980, with Black residents making up more than 40 percent of the city’s total population, Chicago felt like a Black city (at least to a Black Chicagoan). But this was the peak of Black residency in the city and marks the start of a consistent trend of an exodus, with 33 percent of the Black population leaving the city between 1980 and 2017.26 What happened to the land of promise proposition that attracted Black Americans to Chicago nearly a century ago? How had the city failed to fulfill the promise of freedom and equality?

Popular displacement narratives suggest that the reverse migration was driven by a push—an economic force that involuntarily dislocated Black residents from their communities. This is only partially true. Black depopulation has many triggers, both voluntary and involuntary. The demolition of public housing projects during the height of the HOPE VI program, a federal initiative to disrupt the concentration of poverty by replacing public housing “projects” with mixed-income, low-density housing, contributed to South Side population dispersal. There is another group of Black Chicagoans who felt compelled to leave the city because of the disinvestment that left Black neighborhoods with inferior public schools, infrastructure, and commercial services, as well as surges in neighborhood crime. Black families with financial means made the choice to leave the city because public investment had not been equitably distributed on the South Side, as it had been on the North Side. And finally, there are those Black families who simply wanted what many other Americans want—a large home on a spacious lot in the suburbs.

In Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in Black Cities, Brookings Institution senior fellow Andre Perry reminds us that central to the idea of the American Dream is the belief in a land of opportunity in which any person, regardless of background, can—with hard work—climb economic and social ladders to attain a home, start a business, or retire with a security of income. Wealth, as measured by a person’s material possessions, like land or home, minus their debts, is the most common measure of one’s fulfillment of the American Dream. As such, wealth provides economic security and thus enables freedom.27

In 2018, Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program’s research on Black housing assets found—after controlling for factors such as housing quality, neighborhood quality, education, and crime—that owner-occupied homes in Black neighborhoods are undervalued by $48,000 per home on average, amounting to $156 billion in annual cumulative losses nationwide.28 The devaluation of Black-owned real estate means less property tax revenue to support funding for schools, infrastructure, policing, and other public services. The ripple effect of this underinvestment translates to the potential for lower educational outcomes, and less homeowner equity for families to support sending their children to college or starting and maintaining a business.

The racial unrest in 2020 brought about a new commitment to reparative approaches to redress the harm done to Black Americans in the urban spaces of the city. New waves of public debate have forced public officials to put promise into action through publicly funded interventions. Evanston, Illinois, a northern suburb of Chicago, became the first US municipality to pay reparations to Black residents who were victims (or descendants of victims) of housing discrimination between 1919 and 1969. Funded by a new tax on legalized marijuana, this program offers homeownership assistance grants as investments in neighborhoods. City officials outlined as part of the proposal that the “strongest case for reparations by the City of Evanston is in the area of housing, where there is sufficient evidence showing the City’s part in housing discrimination as a result of early City zoning ordinances in place between 1919 and 1969, when the City banned housing discrimination.”29 If equity for Black Americans is really the promise and the desired outcome, financial redress must be part of the act of change and the vision for a just Chicago—and a just America.

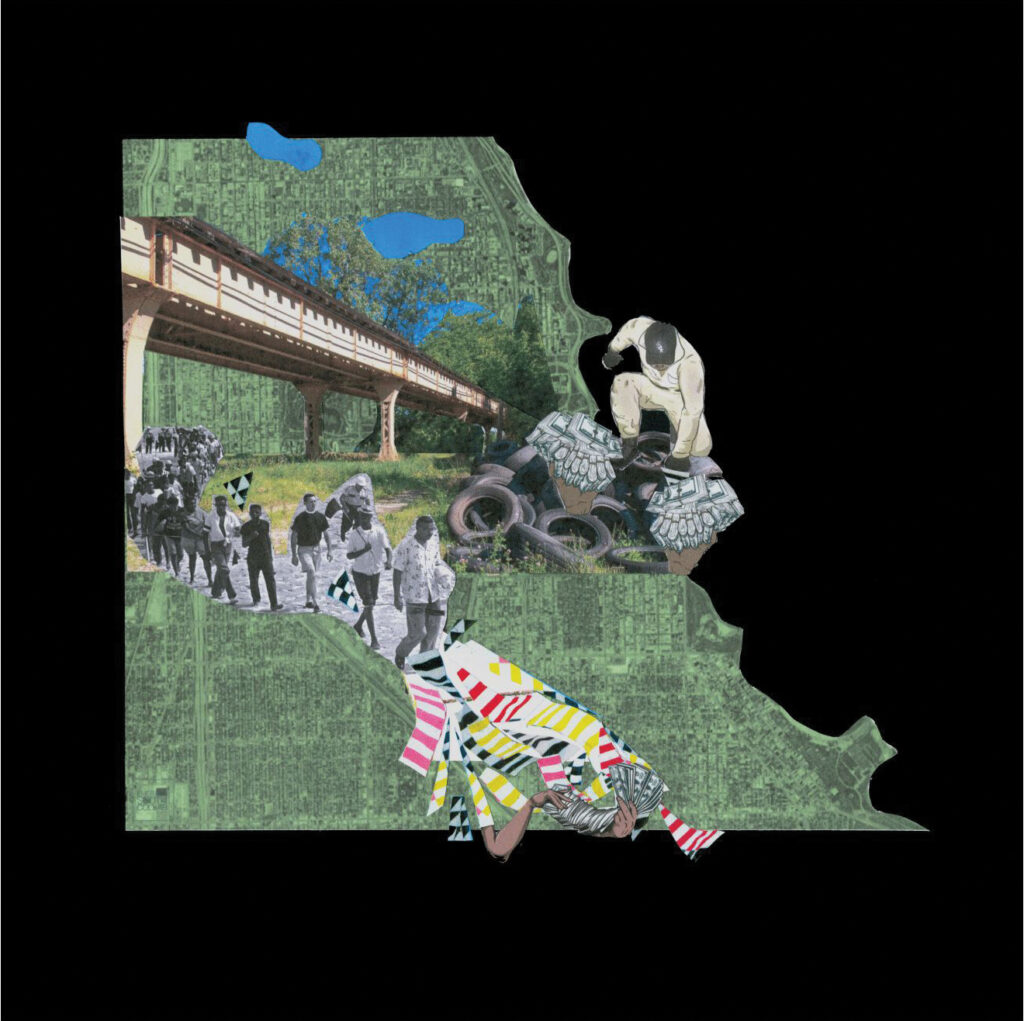

A MARCH FOR OUR LAND recalls the work of organizations like CORE in the early 1960s and the tactic of protest marches as a means to desegregate the public beaches. Imagine a contemporary effort to stage local marches for land reparations. People would take to the streets in neighborhoods of chronic vacancy to demand equitable land appraisals and value, access to capital for reinvestment, and Black land ownership, as promised in the Special Field Order No. 15, issued by Union General Sherman in 1865 to allot plots of land up to 40 acres to some freed slaves.30 Steinbrecher’s photographs of South Side land vacancy are overlaid with images of Black men—both real (CORE protesters) and fictional (as represented in artist Hebru Brantley’s depiction of Chicago-native Chance the Rapper as a superhero of generational pride, power, and hope)—exercising the superpower of Blackness: descending upon the vacant land to reclaim the assets and monetary value of what was taken, devalued, and denied. The case for reparations is undeniable as there is already a precedent in Native American reparations. The South Side belongs to Black Chicagoans—it’s time that they own it as well.