Contracts and the Evolution of Architectural Practice

In architecture, contracts play an outsize role in determining an architect’s relationship with clients and how they work together with builders and other vendors and stakeholders in a building project. Contracts are also an indicator of the state of the profession of the time, and the history of how they have evolved reveals a dramatic increase in complexity in the kinds of building projects that architects undertake as well as a fundamental shift in what constitutes the architect’s expertise and responsibility in the design and construction of a building. Whereas a century ago, for example, architects ensured standards of craftsmanship in construction, today they coordinate and manage the design and construction of buildings that are themselves conceived as multilayered assemblages of industrialized products, each requiring its own specialized subcontractors and experts. In the following discussion, historians Chelsea Spencer and Bryan Norwood talk with a practicing attorney, Jay Wickersham, about the evolution of legal contracts for architectural services, and how the rapid expansion of such contracts reflects equally rapid changes in the profession of architecture.

Chelsea Spencer

Architecture and the construction industry are structured by many different types of contracts and agreements. So perhaps we could start by discussing what we mean when we use the word “contract” in the context of architectural and building practice. What kinds of contracts are we talking about?

Jay Wickersham

Architectural contracts are different from contracts that relate to a single event—the selling and buying of a house, for example—because they shape a continuing relationship between the architect and the client. The process of design and construction may go on for years. It’s important for there to be something in writing, whether it’s an exchange of emails, an American Institute of Architects (AIA) standard contract form, or some other document, which will shape the expectations and behaviors of the parties. And because architectural contracts go on for a long period of time, they have to deal with change, with the inevitability that the project will not proceed as everyone thinks it will at the beginning.

Bryan Norwood

Yes, since designing and constructing a building are complex tasks that take a long time, architectural contracts have to be delineated in ways that take into account change over time. For example, in the United States in the early 19th century, architects began to use executory contracts that scheduled the distribution of the client’s money to the builder when various stages of construction were adequately reached—such as when the basement was built, the first floor was framed, and the roof was complete.1 Architects also found ways of implicitly delineating details in contracts, like describing how particular craft work must be done in a “workmanlike manner” rather than detailing every joint and every measure of quality. As the century progressed, however, contract documents and architectural documentation in general expanded, becoming more explicit and specific.

Jay

There was a real transformation in the nature of contracts when the construction industry started to modernize and industrialize. Throughout the 19th century, clients’ expectations were that buildings of ever-increasing size and complexity should be delivered on time and on budget, because such buildings were major capital investments, and their contracts were the lifeblood of the market economy.

As a result, contracts became more and more specific as to standards of performance, because buildings became assemblages of industrialized products, rather than something using standard preindustrial techniques (meaning they might have resembled the building next door or one in the next village). But we can’t talk about architectural contracts without talking about the role of the builder. The builder is the inescapable third party—implied, even if invisible—in every architectural contract.

Chelsea

Of course, who the third party is in this relationship is a matter of perspective. The building contract, as a two-party agreement between a builder and an owner, is a much older kind of instrument than the architect-owner contract. Throughout most of history, building contracts stipulating the involvement of an architect or engineer were extremely rare, and they still are in the vast majority of building contexts around the world. In architecture, there is a tendency to think of the general contractor as an interloper. But if you look at the early 19th century and before, it’s clear that the architect is just as much an interloper in this process.

In the modern construction industry, contractual relations often have a triangular geometry. The building contract of today is one example: it’s an agreement between an owner and a contractor, with an architect named as a third-party mediator of their relationship. But another crucial instrument is the surety bond, where a third party, the surety, guarantees or underwrites the contractor’s promise to the owner. I think these triangular structures might have something to do with the huge stakes and long time horizons of a modern construction project, which Jay pointed out. Bilateral trust is just not enough to make the risks tolerable for owner-investors. From this wider perspective, we might think of the professional architect as one agent in these intersecting structures of trust. Situated between owners and builders, the architect’s expertise and purported disinterestedness are important, but there is clearly a class dimension at play too, and that has its own history.

Jay

When we look at the relationship between the architect and the builder, we see that a transformation took place in the 19th century. The emergent group of professional architects, which began with people like William Chambers and John Soane and the Architects’ Club in late 18th-century London, had an idealized view of their role. They believed that the architect must not have a financial interest in construction, because he (I use the pronoun deliberately, because all professional architects then were men) had a fiduciary responsibility toward the client to act in a disinterested manner, serving the client’s needs. If there was a dispute between the client and the contractor, the architect was supposed to be a neutral arbiter—even if that meant that he had to confess his own errors in the drawings, which would entitle the contractor to more money.

There was an idealized side to this view of the architect’s professional role. In this world of strangers that comprises the marketplace economy—a world of increasing complexity—the architect was supposed to serve as a trustworthy guide, protecting the client’s interest against exploitation by the builder.

There’s also a darker reason why professional architects wanted to separate themselves from builders, which was founded on fears about class status, and on ethnic and religious discrimination. Many of the leading builders in mid-19th-century America were Irish Catholics. If you could not be an architect while also working as a builder, that effectively excluded these Irish Catholics from entering the profession for a very long time. That was, at least, the idealized notion of what it meant to be a professional architect. Bryan, I know you’ve done a lot of research on what architects actually did in the 19th century, and to what extent they could or could not carry out this idealized professional role.

Bryan

Many architects in the antebellum US said that what they did as professionals was bill at 5 percent of construction costs for the work of designing and mediating between the builder and the client during construction. In practice, when you flip through the daybooks of many of these architects, what you find instead is that they billed for the majority of their work as designs sold for a fixed price. You will even see that these architects sold specifications and contract documents themselves, along with design drawings, for a fixed fee. There was a substantial gap between the vision early 19th-century architects had of their profession and the reality of how they were making money.

Jay

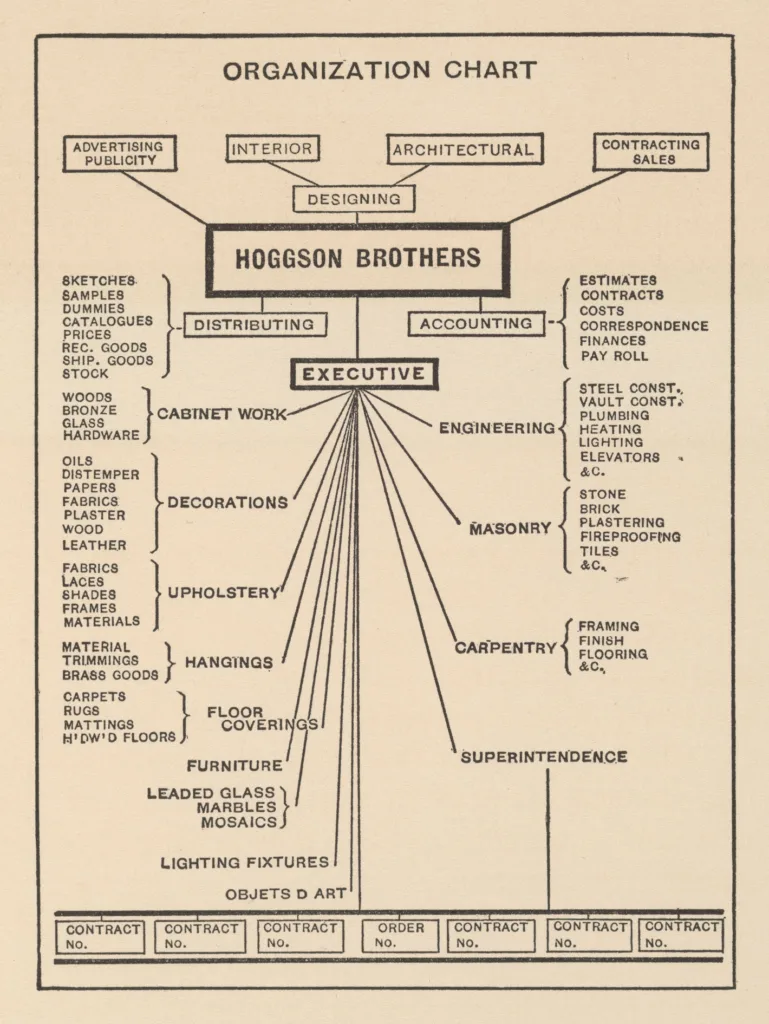

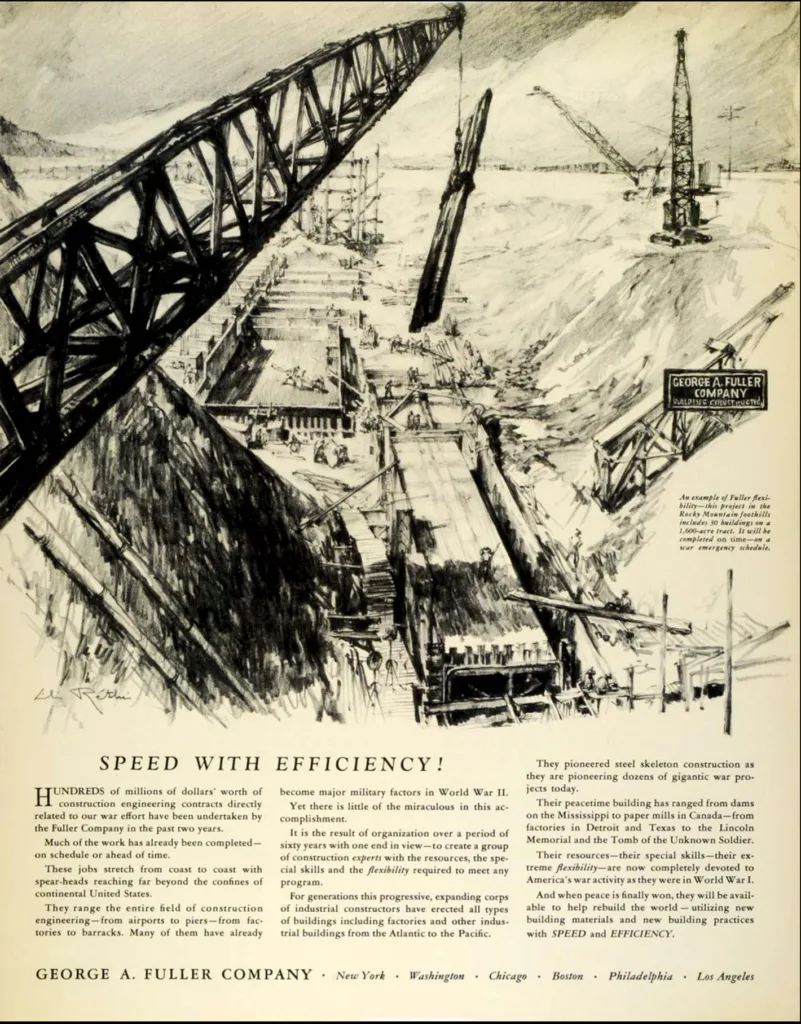

I wonder if we could jump ahead to circa 1900, when George A. Fuller invented the role of the modern general contractor with a national practice. Chelsea, what have you found from your research on how the construction process changed, and what the contractors’ relations were with the architects of their era?

Chelsea

By 1900, the practice of general contracting—where a single contractor takes responsibility for the construction of an entire building and commits to a set schedule and price structure—had become the normal way that large projects were built in most US cities. The idea of a lead contractor overseeing a whole project wasn’t necessarily what was new—carpenters and masons had been taking on this role for a long time. It’s only in the second half of the 19th century that the building contractor as such became a specific occupation of its own. Before that time, the word “contractor” was really only used in legal contexts to refer very literally to somebody who performs a contract. But by the end of the 19th century, “contractor” meant building contractor, and their role was just as much to enclose and take responsibility for the many risks of building as it was to actually manage the work. Architects were slow to notice the rise of the general contractor. It was really only at the turn of the 20th century that architects realized that by handing over responsibility for the grubby, risky parts of architectural production to contractors, they had also allowed them to amass quite a lot of capital and power in the industry.2

Jay

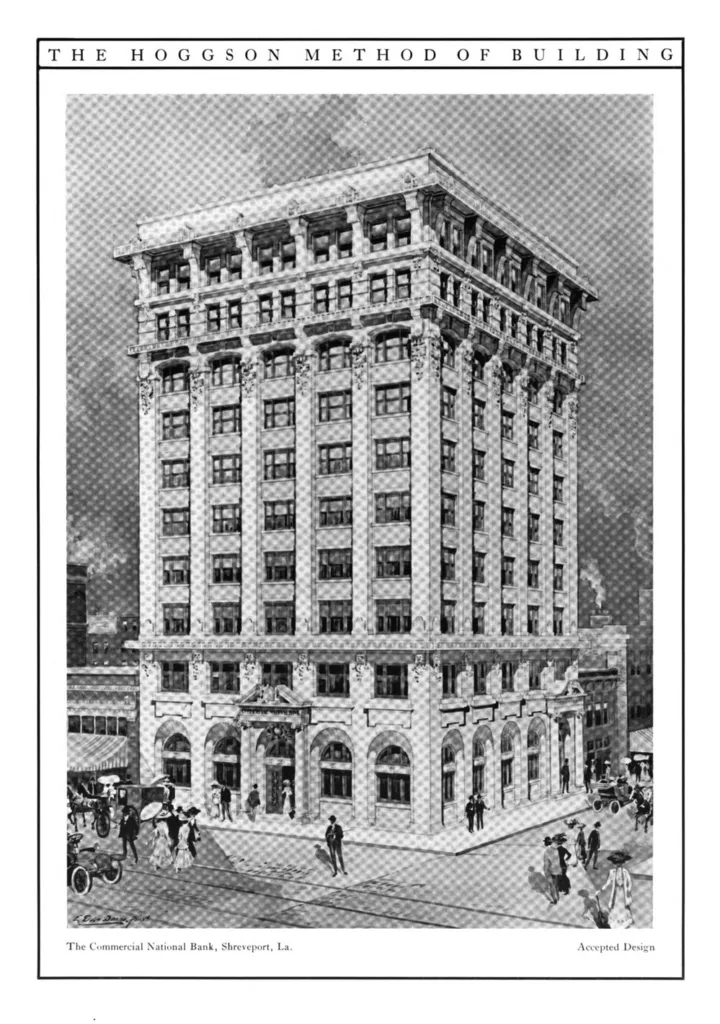

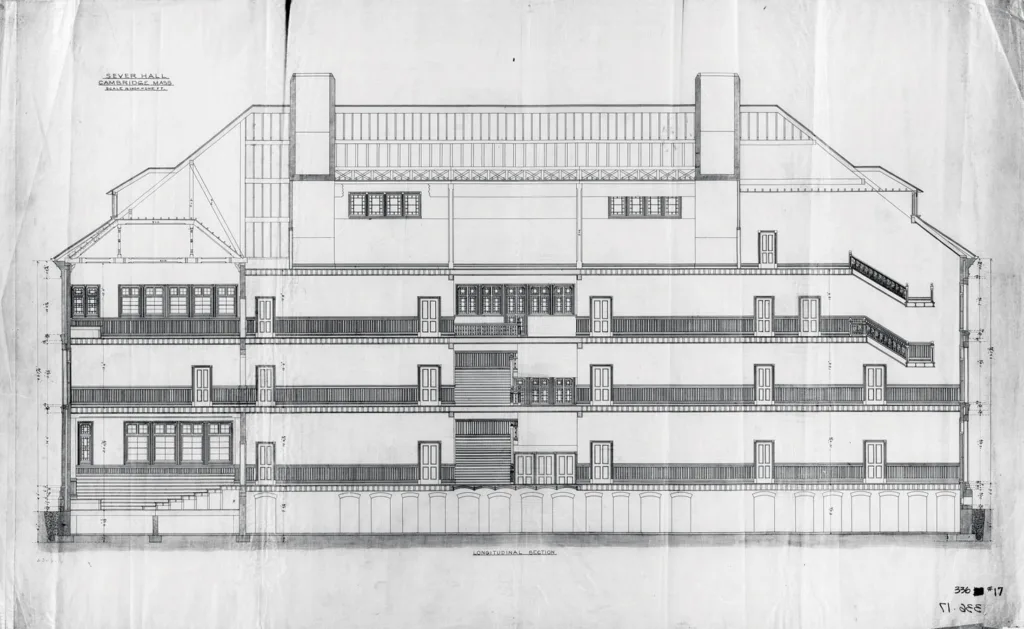

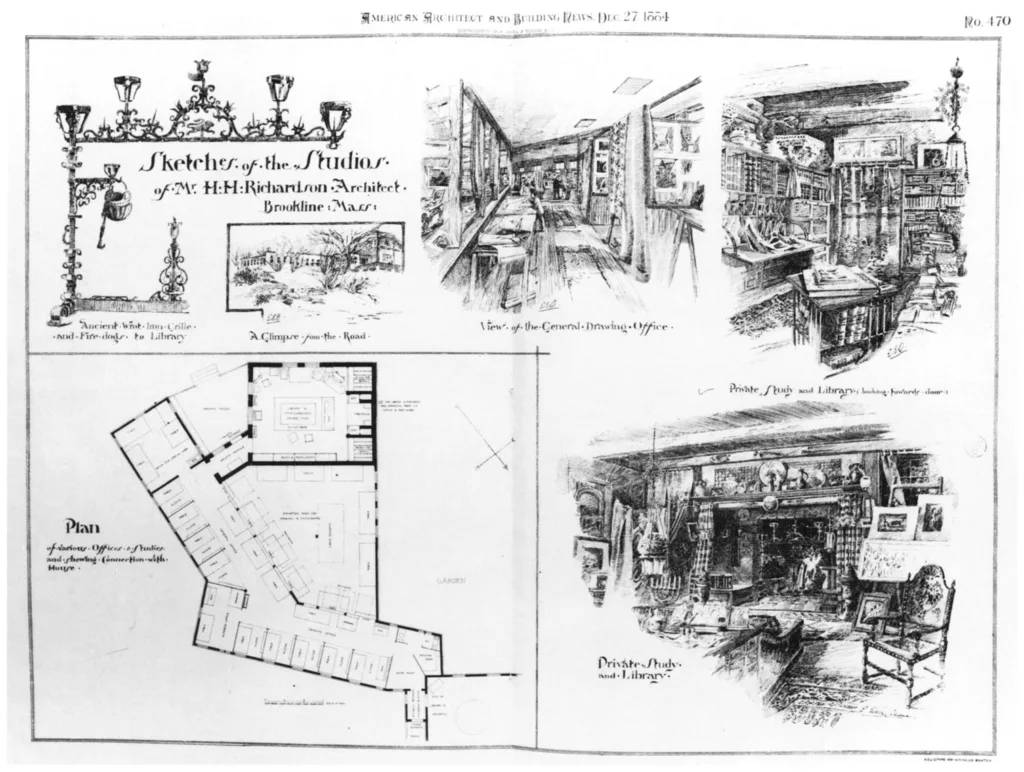

That also speaks to the transformation in architectural practice that happened around 1900. With the rise of the general contractor, the architect started to produce a much more detailed set of plans and specifications. Around 1885, H. H. Richardson’s office produced what we would consider today to be a design development set of plans, sections, and elevations, and perhaps a few other details, with a 10-page set of specifications, for a project such as Harvard’s Sever Hall. By 1900, you see enormously detailed plans and specifications being produced by architects, because by then there was a general contractor who was being asked to make a competitive bid. These contractors were looking for specificity so that they could take on the risk of signing a contract that committed them to a fixed price and a fixed schedule.

So I think there’s a powerful symbiosis between what architects create and what general contractors need, and that, in turn, led to the development of the AIA’s standardized forms. By 1900, the AIA was producing not only a standard form for an architect’s contract, but also a standard form for a construction contract as well. The architectural profession was trying to maintain as much control as it could over what, at the time, was a rapidly growing construction industry.3

Bryan

The language that you see in contracts from the early 19th century in the US (especially starting in the 1830s in larger cities such as New Orleans, New York, and Philadelphia) is very similar. So I think there was a push toward standardization in the early 19th century, and architects were trying very hard to find language to control not just the immediate design but also the modifications and clarifications that inevitably happen over the life of the construction process. I think they believed that if you could write a really good contract, then architecture could be executed through enlightened relationships that were rational and that everybody voluntarily consented to, and that, in turn, would save time, money, and stress.

Jay

So it would make sense, in terms of what both of you are saying, that in the 1920s there would be a renewed push for standardization of the building industry.4 A key figure was Herbert Hoover, who had been a very successful engineer before he went into politics, and who was then serving as the secretary of commerce. And as part of this process of standardization, there was a continuing push toward the use of standardized contracts, first in the 1920s and then in the 1950s.

My sense is that the 1950s were a kind of watershed moment for the standardization of architectural practice. That’s when every state began licensing architects as professionals, effectively requiring a professional educational degree. Does that make sense as a narrative—that from the 1920s at least up through the 1950s, there was a continuing push toward efficiency and standardization of practice as well as of construction?

Chelsea

That does make sense. Back in the 1880s and 1890s, the US economy was not yet an integrated market. Contractors were trying to organize themselves into a national association then, and they could hardly agree on anything because the conditions of each local building industry were too different. But something happened between the late 19th century and the early 1930s. Part of it was an approach to regulation, where the national market was actively constructed as an object of federal governance. But I think the introduction of standardized documents was also important, because they helped codify a certain set of expectations as industry norms and made parties more readily intelligible to each other.

Jay

In the time of unbridled competition in the late 19th-century building industry, professional architects were working very hard to free themselves from competitive bidding. Going back again to the late 18th century, the idea emerged in Britain that architects should be paid according to a fixed fee schedule. As Bryan noted earlier, the fee was originally supposed to be calculated as 5 percent of the construction cost, then 6 percent. By the 1950s, there were these elaborate sliding scales that every AIA chapter published, which fixed the percentage of construction costs based on the size and type of the project. And if an architect offered to do a project for a fee less than that, they would be censured or even kicked out of the AIA.

Now, even in 1950, half of the architects in the country weren’t AIA members, so again, to Bryan’s point, how well that requirement was complied with is an open question. But certainly the high-end AIA members took very seriously this idea of fixed fees. It allowed them to know in advance what their compensation would be. This was another way in which the architect’s concept of professionalism reinforced a sense of class status, a separation from the crass hurly-burly of the marketplace.

Maybe now we could jump ahead to the late 20th century. There is still a myth in the profession of this golden age, when every client accepted the AIA contract, every builder used the AIA contract, and everybody in the profession followed the AIA fee schedules. In fact, all of that uniformity around professional practice started to fall apart in the 1970s, under what was then called deregulation during the Carter and Reagan administrations and what we now call neoliberalism. The fee schedules were undone by a series of lawsuits and enforcement actions by the Department of Justice, which declared fixed fee schedules in any profession, not just architecture, an unlawful monopoly that violated the Sherman Antitrust Act.

At the same time, you can see that the construction industry was shifting from the competitive bid model—where you wait for the architect’s drawings to be completed before bidding on them—to the modern-day model, where the construction manager is at the table from day one with the architect and the client and delivers the project on a negotiated cost-plus basis.

That’s my perspective, both in looking at this recent history, and as a working lawyer, in considering the contracts I deal with today. In our practice, we are almost never able to propose AIA contracts for use on a project of any complexity. The client always has their own forms, developed by their lawyers or their construction advisors. These client forms may draw upon AIA models, but they’re much more heavily weighted toward the client’s side. And, of course, fees today are competitively bid. There are no longer AIA fixed fee schedules, so it’s a very different world that these contracts are now helping to shape, compared to what you would’ve seen in practice as late as the 1960s and even the 1970s.

Chelsea

The golden age of simple, straightforward contracts is indeed an interesting little myth. Even with the AIA contract, it’s very easy to write “see attachment” in one of the blanks, and append some monstrously complicated rider. This became a common practice pretty much immediately after the release of the first Uniform Contract in 1888.

I am skeptical of claims about the increasing complexity of contracting today. We certainly document everything in a very fastidious way now, so the complexity is very legible—we have reams and reams of paper and terabytes of data manifesting the complexity. But much business throughout history has been done on the basis of implicit contracts, such that very complex and nuanced expectations can be mutually understood—and in some cases legally enforced—even if unspoken. Scholars have argued that written building contracts from earlier periods, which may appear so remarkably short and simple to us today, were not expressions of naivete but were enmeshed in a dense web of other unspoken obligations and norms that had just as much binding force as a written contract does today.5 So when we speak of practice today, are we conflating complexity and explicitness—a lot of words on paper?

Bryan

I think the 19th century was as complex and messy and uncertain and confusing and laden with risk and chaos as the 20th and the 21st centuries. But there was a lot less paper relative to the building process. In the contracts and the specifications, architects used the word “workmanlike” a lot, which meant do it the way that everybody else was doing it. So while things might have been implied in the sense that they were not on paper, that knowledge and expertise and responsibility existed somewhere.

It seems to me that one of the key through lines in the story of the architectural contract in the US that we’ve been discussing is capitalism. If we think about the contract as a capitalistic strategy for seeking as much gain as possible in the future and off-loading as much risk as possible onto other parties, one of the questions we might ask is where is the risk being placed? In early 19th-century documents, I see architects pushing risk onto builders. When these documents became more complex and multifaceted, everybody was still trying to push risk onto somebody else. Where was the risk landing at these different stages?

Jay

That’s a great question. What I am seeing in practice is that there are two principal ways in which the old system has been reshaped in response to risk shifting. Both of these employ contracts under which all the parties are supposed to be working in a more cooperative way. One is the increasing use of design-build, an arrangement in which the client has one party to point to who has responsibility for both designing and building the structure. In a way, this underscores Chelsea’s point earlier that construction contracts long predate architectural contracts. It may be that the increasing use of the design-build contract represents a return to how it worked in medieval and Renaissance and Baroque Europe.

The other model, which has gotten a lot of attention in the professional press but is not nearly as widely used as design-build, is the three-party agreement model known as integrated project delivery, or IPD, which is intended to be a sharing of the risk. I’ve negotiated a number of these contracts as well, and I’ve found that they’re not all that different from design-build. Clients are still trying to off-load as much risk as possible onto the builders and the architects.

I actually find the most interesting thinking about architectural contracts to be about considering the different roles that architects can play, and the tailoring of contracts to those roles. Increasingly, on a large and complex project there may be several different architects collaborating on the design. As lawyers, we try to help everyone be clear from the start about how this team of architects, clients, and builders is going to work together over the next few years. And from that kind of design thinking—about the structure and process of design—we can develop the language of the contract itself.

Chelsea

Looking back over the 19th and 20th centuries, I can’t help but wonder about the political consequences of the architectural profession’s adoption of contracts as its instrument of choice to achieve its material effects in the world. Even setting aside the antagonistic relationship between architect and builder created by the traditional design-bid-build contract, it’s worth asking whether the framework of contract itself, predicated on an idea of liberal economic personhood, has brought with it a certain model of social relations that constrained the kind of practice architecture could be. Has the profession placed too much faith in a linear, deterministic model of contractual time? I think in architecture there remains this imagined ideal of a project in which things turn out exactly as described in the bid documents. Invariably they do not, but professional practice, at least since the 19th century, has generally been intolerant of the contingency of the building process.

In defining ourselves foremost as parties to a contract—an enforceable promise backed by the threat of litigation—what kind of politics is that? Was there some other possibility? Some other way of arranging ourselves? The other entity that we haven’t mentioned in this conversation on contracts is the public. This is not a coincidence. When we talk about contracts, we’re talking about private law, between individuals. Does the contract—as the essential medium linking architecture to building in the modern world—make the professional private practice almost structurally ill positioned to fulfill architecture’s more civic ideals, to act meaningfully with and for the public interest?

Bryan

Our visions of architectural authority, certainty, independence, and freedom are also linked to the way we imagine ourselves to be able to be free subjects in the market. That should give us pause.

Historians of contracts emphasize that the language of the contract is an economic and legal correlate of the dream of the Enlightenment subject: that the contract expresses a belief in free subjects that think about an agreement and then voluntarily assent to its terms.6 In this considered, voluntary assent you have ownership of yourself and your worldly projects; as Kant said, you are thinking for yourself! And that is core to the vision of architecture that we have come to know, right? That has given us the idealized model of architectural design and practice, and so much of our discourse revolves around it.

Jay

Maybe another way to say this is that contracts are the lifeblood of the capitalist marketplace where, for better or for worse, all architects today must work. I completely agree with you that our notions of ourselves as creators and innovators are deeply, deeply influenced and colored by the assumptions of the marketplace. So where is the role of, the voice for, and the interests of the community?

My mentor, the lawyer Carl Sapers, who taught for many years at the GSD, would steadfastly say that an architect is a fiduciary. That means that you put the interests of your client ahead of your own interests, and you put the interests of the public ahead of both.

So how does that work? For most of the 19th and 20th centuries, architects assumed that they were inherently doing the public’s work because they were trained to design buildings that were safe, functional, and beautiful. Today, the voice of the public is expressed from the outside, through governmental regulation. A whole host of regulatory systems, from environmental impact reviews and historic preservation laws to zoning and building codes—all of them offering opportunities for neighbors and advocacy groups to express their own views—now interfere with the private contractual relationship between architect and client. Often I have heard architects who espouse liberal, community-based values complaining bitterly about the infringements upon their creativity that these regulations have caused. That’s another way in which the ideology of the marketplace can make it hard for architects to acknowledge that regulation is a way in which law is expressing the voice of the community.

2 In Cass Gilbert’s speech to the AIA in 1906, he reflected upon the changing dynamic between architect and contractor. He articulated that architects started working with general contractors because they wanted a single point of responsibility on-site—for general oversight but also to take on liability for what gets built. Part of the architects’ claim to professional status in the 19th century was a refusal of liability for construction defects, and courts came to agree that architects were bound only to exercise reasonable care in designing and supervising construction, not to guarantee the total perfection of their designs or the building that was built. Contractors saw this as an opportunity: they recognized that taking on construction liability was valuable to property owners, and they made it their business to bear and manage that liability.

3 In 1888, the AIA collaborated with the National Association of Builders to produce the first nationally standardized building contract form in the US. In this fraught process, the builders acknowledged that the contract was not ideal but agreed that it was an improvement upon the chaotic and unstructured status quo; however, it took the architects at least a decade to start using the form.

4 In the 20th century, the United States was effectively a single market for practice across the states, whereas in Europe it was very difficult to practice across national borders. Even in the 19th century, architects like H. H. Richardson; McKim, Mead & White; and Daniel Burnham, and general contractors like the Fuller Company and Norcross Brothers, were building all across the country. This triggered a push toward standardization of the design and building process as a way of reducing transactional costs, and making the national marketplace more efficient.

5 Catherine W. Bishir, “Good and Sufficient Language for Building,” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 4 (1991): 44–52.

6 See, for example, P. S. Atiyah, The Rise and Fall of Freedom of Contract (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979); Amy Dru Stanley, From Bondage to the Contract: Wage Labor, Marriage, and the Market in the Age of Slave Emancipation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998); and Brook Thomas, American Literary Realism and the Failed Promise of Contract (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).