Designing for Endless Fire

Wildfires are nothing new in Los Angeles. Nor is the overlap between fire and the cultural imagination in Southern California. Literary, artistic, and cinematic depictions of the city and its architectural landmarks in flames go back more than a century, an apocalyptic canon that includes work by the painter Edward Ruscha (The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, 1968), the writer Octavia Butler (Parable of the Sower, 1993), the film director Mick Jackson (whose 1997 blockbuster, Volcano, sends a river of lava down Wilshire Boulevard) and, most prescient of all, Nathanael West, whose 1939 novella, The Day of the Locust, features a protagonist, Tod Hackett, who is working on a giant painting called The Burning of Los Angeles. As Joan Didion wrote in Slouching Towards Bethlehem in 1965, in a much-cited essay on the Santa Ana winds that many Angelenos are weary of by now (though few would dispute its conclusions): “The city burning is Los Angeles’s deepest image of itself.”

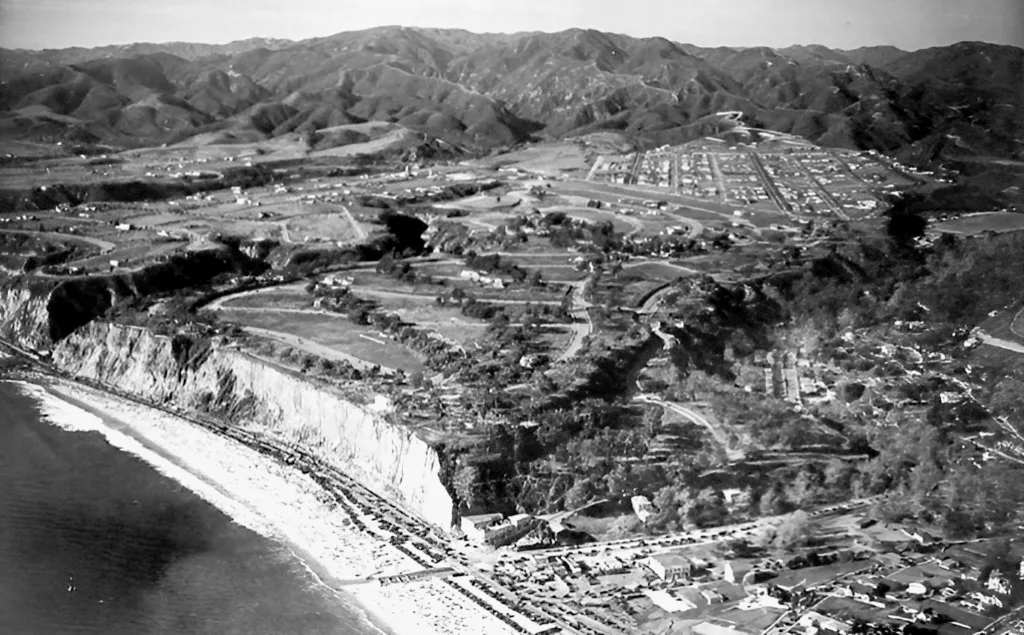

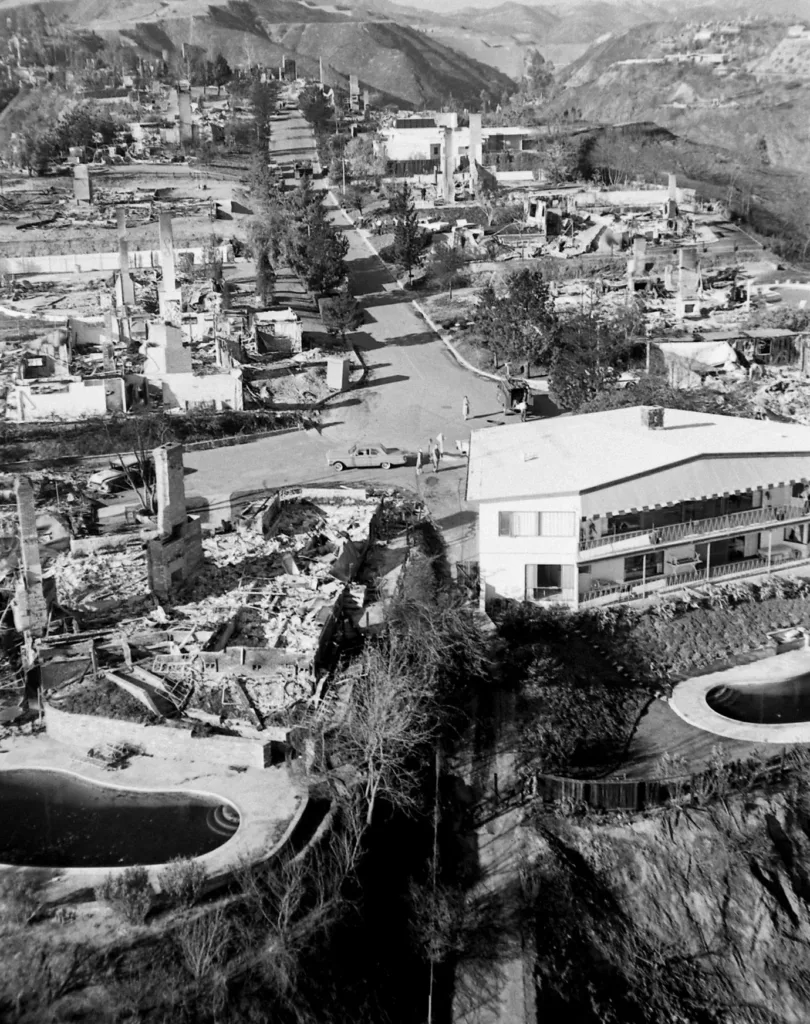

Yet no LA resident could possibly have been prepared for the scale of January’s twin wildfires in Pacific Palisades and Altadena, which killed 29 people and destroyed more than 15,000 buildings, including more than 11,000 houses. (Until this year, the most damaging blaze in the city’s history was the 1961 Bel Air fire, which consumed 484 houses.) Hurricane-force winds that began whipping through Los Angeles County in the first week of the new year carried the blaze into neighborhoods, especially in Altadena, where homeowners hadn’t thought of themselves as especially vulnerable to wildfires. Yet in an era of climate shock, it’s clear that Angelenos’ mental map of fire risk needs to be dramatically expanded. So, too, does our vigilance about the relationship between longer fire seasons and dangerously poor air quality.

Some architects and urban planners, meanwhile, have found in the LA fires ample evidence that our approach to locating and building houses is similarly out of date. But there might be something to be said for a different, even opposite, conclusion, namely that there are long-standing lessons about fire, architecture, and urban design that have slipped from the cultural conversation but now could be revived and reframed to help us tackle a specifically 21st-century set of challenges.

To explore these and related questions, I had a discussion in March with a group of experts in architecture, planning, wildfire, and public health to discuss the LA fires and the nascent recovery process. Over Zoom, I spoke with Frank Frievalt (retired fire chief and director of the Cal Poly San Luis Obispo Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) Fire Institute), Margot McDonald (licensed architect, professor, and Cal Poly faculty liaison for the WUI Fire Institute), Joseph G. Allen (associate professor of exposure assessment science, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health), Dana Cuff (professor, UCLA Architecture and Urban Design and founding director, cityLAB), Michael Maltzan (principal, Michael Maltzan Architecture), and Arthi Varma (deputy director, Los Angeles City Planning). What follows has been edited for length and clarity.

— Christopher Hawthorne

Christopher Hawthorne

Frank and Margot, can you help us understand what accounted for the absolutely devastating scale of the Palisades and Eaton fires? I think everybody’s familiar with Los Angeles being vulnerable to wildfires, but not at this scale.

Frank Frievalt

Three things led up to this, really, beyond the unprecedented wind speed during these fires. First is the general accumulation of fuels (not all places, some areas are burning too frequently) for wildfire, an unintended consequence of federal fire policy. The second is increasing population density, especially since World War II, and continued development out into fire-dependent landscapes. And the third is climate change. Climate change didn’t cause those fires, but it certainly exacerbated them.

The last thing I would add is that we’re mistaking these for wildfires. They’re not wildfires. They start as wildfires. But it’s the multiple simultaneous ignition of structures, from what we call “ember cast,” that overwhelms our systems. At that point, it’s a structure-to-structure, urban conflagration.

Margot McDonald

Then there’s the reliance on synthetic products and synthetic fabrics. Consider how many building elements we’ve transitioned to synthetics and petroleum-based products. As we think about buildings as fuel—in terms of what buildings are made of—that’s exacerbating the problem once fires begin.

Christopher

Now a question for the whole group: Does climate risk require us to rethink, in any fundamental way, how we plan and build neighborhoods in LA and cities like it? I’m thinking about the materiality and resilience of individual buildings, following up on what Margot said. And more broadly, should we be pulling back residential development that edges into wooded areas, or is increasingly at risk of flooding?

Joseph G. Allen

In terms of building material itself, we’ve had a historic problem in how we design and build our buildings, where we haven’t followed health-first principles. We’ve really lost our way over the past 40 years. I often refer to this as the sick-building era. This ties into healthy buildings, green buildings, and resilient buildings. And you can see some of that in the emissions we saw from the fires.

We saw signs of elevated lead all the way downtown. That’s from the historic use of lead in buildings. Once it was released, it really blanketed the region. When we think about materials, we have to think about the so-called legacy hazards and pollutants that have been banned since the 1970s but still present a problem: lead, asbestos, PCBs [polychlorinated biphenyls]. And then we have “safe” alternatives that turn out to be not so safe. A lot of these are petroleum-based chemicals. So it’s past time to revisit how we go about designing our buildings. These toxic chemicals are bad for us in indoor environments even on a regular day, and we know that they can cause other problems when they’re combusted and emitted.

Dana Cuff

There’s an unspoken problem underlying the Eaton and Palisades fires, which is that people don’t want to get in the way of rebuilding single-family homes. But none of the things that Joseph just talked about would be as problematic if we decided to confront that issue. I understand that the trauma of losing your home is so great that no one wants to intervene, especially from the city level. But I also want to clarify something Frank and Margot said that I think could be misinterpreted: density isn’t the problem. Rather, it’s an insufficient density of the structures themselves that was problematic—our multifamily structures are better prepared in terms of fire hardening than single-family dwellings.1

As we start to rebuild, some people say, “Oh, we should put the houses even further apart.” I don’t think that’s the solution Joseph is suggesting, and I’m sure Margot and Frank don’t think that either, but in my view density is part of the solution here. We should not be rebuilding without making sure that we have more housing when we’re done, not less. In fact, the staging of the fire rebuilding is encouraging, in some respects. For instance, there are people in Altadena moving RVs onto their properties while they build an ADU [accessory dwelling unit], and then they move into their ADU while they rebuild their primary residence. I think that kind of ecological rebuilding is smart.

Michael Maltzan

For people outside of LA, and for readers of the magazine, it’s important to note that there’s a real difference between the way the Palisades was built historically, and what the topography is like there, and what Altadena and the Eaton Canyon areas are like. There are significant differences in their socioeconomic profiles, ethnic histories, and how these communities evolved over time, all of which will profoundly affect rebuilding efforts. These fires, and the devastation of these communities, also deeply disrupted those existing balances.

I doubt anyone in the insurance industry was shocked by what happened in the Palisades. Many people knew the risks of those areas. But I think Altadena was shocking to people in the city because the fires and the scale of the devastation moved so far beyond the typical wildland-urban interface. This challenges our entire conception of the city—for instance, our assumptions that a six-lane highway might stop a fire like this, or that major commercial zones might create a firebreak. The limits of that kind of thinking were laid bare when you saw how far these hurricane-force ember storms traveled.

That’s important because it requires us to think about how we rebuild and how we think about the city moving forward, at multiple scales and levels. I was part of an AIA [American Institute of Architects] forum the other night. It was remarkable because there were many people involved in the rebuilding, bringing dozens of very good ideas. Many of those ideas were extremely detailed and specific about smarter rebuilding, material selection, hardening strategies, and how landscape architects might rethink the landscapes in and around these places to create more fire resistance. But the most consequential and challenging questions were around topics like permit reform, zoning reform, the economics of rebuilding, and insurance regulations—and how those factors influence rebuilding in ways unlikely to enhance fire resistance. Architects, landscape architects, and planners can’t solve these interconnected, systemic issues alone.

We’re only one part of the larger equation. Finding ways to create more collaboration among all of those different related and interconnected groups, for me, is the crucial challenge. It’s not only how you rebuild in these areas, but how you produce the necessary strategies for continued development in the city as a whole, given what we now know about the large-scale effects of these types of events.

Christopher

As Dana was suggesting, it is almost always a nonstarter for an elected official to stand in the way of a homeowner who has insurance proceeds in hand and the desire to rebuild in much the same way that they were living before. That’s understandable on a political level, on a case-by-case level. But if you multiply that by a thousand, by 10 thousand, then we’re basically recreating the conditions that led to the disaster in the first place. This has been true in every climate disaster that I’ve covered going back to New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina, 20 years ago. So, when it comes to the larger land-use questions, about where we locate new housing and density in an era of climate shock, how do we begin to allow that conversation to get some kind of political traction?

Arthi Varma

That is really the question of the moment. And I want to touch on some of the other comments made earlier, because density and population change are parts of the conversation—the way we used to be able to develop as a city, compared to what we have now. Population change is something that we as a city are required to think about; we don’t get to control it, but we have to respond to it. Creating density is an important component of that response, and where we create that density is the question. We need to be mindful of environmentally sensitive areas and we need a larger cultural shift around how we’re rebuilding that incorporates all of these issues along with home hardening and sustainable defensible space.

While I hope this doesn’t happen again—certainly not at this scale—we have to be prepared that it will. As Michael said, some of those Altadena communities weren’t even in the very high fire-hazard severity zone. So we have to be prepared for urban wildfire not only affecting areas where you think, “Oh yeah, I thought that might happen at some point.” In the neighborhoods affected by the fires, there’s trauma, and there are different ways the city needs to provide support. We need to take a step back and look at the issue more broadly: What are we doing as a city to rethink the way we’re developing from a land-use perspective, in order to best position ourselves for future events like this?

Dana

It’s great to hear Arthi talking about density, and the benefits of density. This is a new conversation that architects have played a role in, from the Low-Rise housing competition forward.2 We’ve all been thinking about growing the city differently. And it seems to me that it’s at times of radical change—most recently the postwar suburban growth in Los Angeles and elsewhere—that these kinds of transformations occur. We have houses equipped with fire sprinkler systems, we have five-foot side-yard setbacks—those are all the result of fire-related regulations. We instituted those into our regular building code and planning code. And we’re at one of those moments again, when top-down regulations could insist on changes that are for everyone’s benefit. But there’s also a clear model of how we might do bottom-up change in the little house that didn’t burn in the Palisades fire, the one that everyone drove by that was designed by Greg Chasen. It wasn’t particularly remarkable, but it withstood the ember storm through simple geometric form and fire-resistant materials. People looked at it and said, “Oh, if that survived, I want one of those.” Change happens when people can kick the tires and see homes that show how you can do this better. And we ought to have insurance incentives to support that. Why aren’t there big benefits for houses that are both individually hardened and in communities that are immunized to some extent against fire? That would incentivize further resilience programs.

Christopher

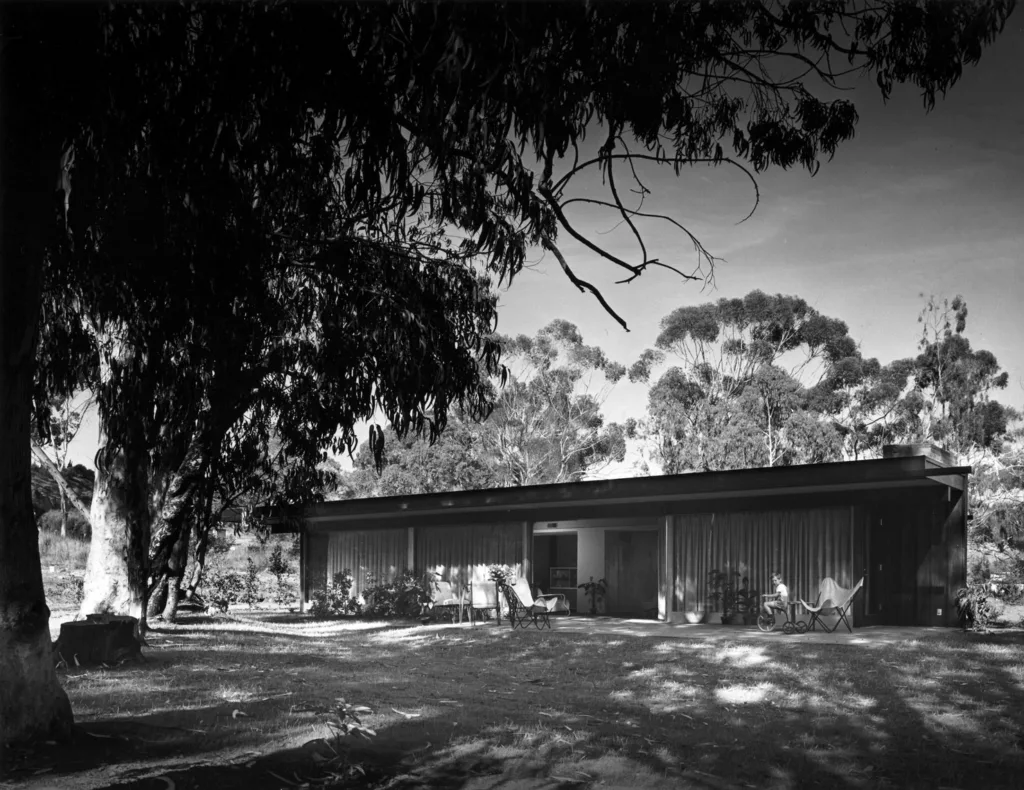

I’m so glad you mentioned the kick-the-tires idea, Dana. People forget that the Case Study Houses, the paradigmatic examples of postwar modernist single-family housing, were open to the public before the clients for those houses moved in. Hundreds of thousands of Angelenos walked through those buildings. They lined up to see them! That was a significant part of the impact they wound up having.

Dana

This project that cityLAB’s doing right now, “Small Lots, Big Impacts,” has really pivoted toward fire resilience. It will be like a new set of Case Study Houses that show what the next generation of Los Angeles will look like—in terms of sustainability and fire resilience as well as more compact living.

Frank

We had an unacceptable level of fire-related life and property loss in the US through the 1950s and 1960s. In 1973, a national commission generated a report called “America Burning.” At that time, we were running about 11 million calls annually in the US to fire departments, and about 27 percent of those were interior structure fires. But over time, refinements in architecture, urban planning, building codes, fire protection, and engineering drove that number down. By 2019, the US call volume had gone up to 37,000+—but of those calls, interior structure fires went from 27 percent of the total to 1 percent. Now we need to take the kind of expertise that got us those results inside structures and bring that competency to the outside of buildings. This can be done.

Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images.

Insurance is really just the tip of the iceberg. This risk contagion is transferring rather quickly into the real estate market, the lending markets, and most recently the general obligation municipal bond market. Very quickly, we’re going to enter an interim space where local government will start to feel a financial hit for not mitigating wildfire risks. Property values will be degraded, but I think what will really get their attention is if the city of Los Angeles bond rating dropped, say, by two points, and it was specifically due to wildfire risk. Remember, you service general obligation bonds with property tax, from properties that are increasingly going to be underinsured or uninsurable. In March 2025, Standard and Poor’s made it clear this was going to start happening.

Joseph

I’d like to expand the conversation a little bit. We’re rightly focused on the areas that have been most impacted during the wildfires and talking about how we rebuild better. But the hazards associated with wildfires extend far beyond what happens in the burn areas themselves—the burn-scar area. We had high levels of smoke that blanketed an urban population with millions of people. We know that we have elevated levels of lead. We know that we have continued emissions from the burn-scar area to adjacent populations. We know that outdoor air pollution penetrates into homes, offices, and schools. But there are simple, low-cost filtration solutions that can be rolled out right now across LA and every other city. Architects can design better filtration into buildings. Building standards and codes can be improved.

Since the Eaton and Palisades fires, California has had 30 fires! Thirty wildland fires from January to March. This means the region is continually blanketed in wildfire smoke. And this is not confined to one area. It’s happening all across the country. Wildfire smoke influences brain health, mental health, anxiety, heart health, lung health, and reproductive health. There’s an increase in emergency-department visits within days of these wildfire events. I looked at the data right now in the Palisades and Eaton fire areas: our outdoor pollution levels are above a safe level, unrelated to the fires. So when we think about building design resilience and what we can do, part of that is just taking these simple measures to keep people who are still in their homes safe from the impacts of wildfire smoke—both during the acute event and afterward. I want to be sure that’s part of the conversation. There’s actually a great deal we can do with our buildings and structures to keep people safe.

Michael

This is a super interesting point. One of the complexities I’ve found in talking about these fires is that you’re constantly whipsawed between thinking about the specific, localized response, on one hand, and the broader effects of the fires on the other—physical effects as well as psychological effects. There are also effects related to the identity of the city. LA is deeply fragmented—with many cultures, communities, ethnicities, political differences, and economic differences across the city. These devastating events reveal just how separated and fragmented the city is. We’re doing an installation for the Milan Triennale that Stefano Boeri is organizing. The theme is “inequalities,” and we’ve pivoted over the last few months to talking about the fires. We’re looking at the satellite maps of the smoke plumes from Eaton Canyon and the Pacific Palisades. You can lay those smoke plumes on top of all sorts of analysis and data showing how economics separate the city, how densities separate the city, how histories separate the city. But at the same time, you see how much of a fiction those separations really are. In some ways, these kinds of catastrophes offer an opportunity to look again at how deeply connected the city is.

Christopher

As LA rebuilds, to what extent can it look back to earlier lessons, or lessons from other places, about some of these questions: fire safety, risk assessment, community building, and community rebuilding? These can be specifically architectural lessons, or lessons related to planning more broadly, or histories of approaching fire risk, or Indigenous knowledge. And how do we fold those lessons back into contemporary architectural practice, planning practice, and what schools are teaching?

Dana

I’ll just take it to a slightly different place, tying Joseph’s and Michael’s comments together, about the ways these disasters impact us. It’s a collective trauma, so it’s important that we understand it that way—not exclusively through private property, but through a community-based perspective. There are a few examples that not only demonstrate a response to disaster but also serve as community reminders. They can seem a little dire at times, like the tsunami towers in the Japanese coastal towns that show how high tsunami levels can be. People see those every day and know that this is how high you have to get to be protected. In Australia, bush-fire shelters are at a neighborhood scale—usually they’re at schools—as a kind of a space of last resort. I’m thinking about how we move toward shared responses that are actually visible, in that same kind of kick-the-tires way. I must be a very literal person, but I think that when you can see things—this is a Hannah Arendt notion, too—you believe they’re part of your reality.

Frank

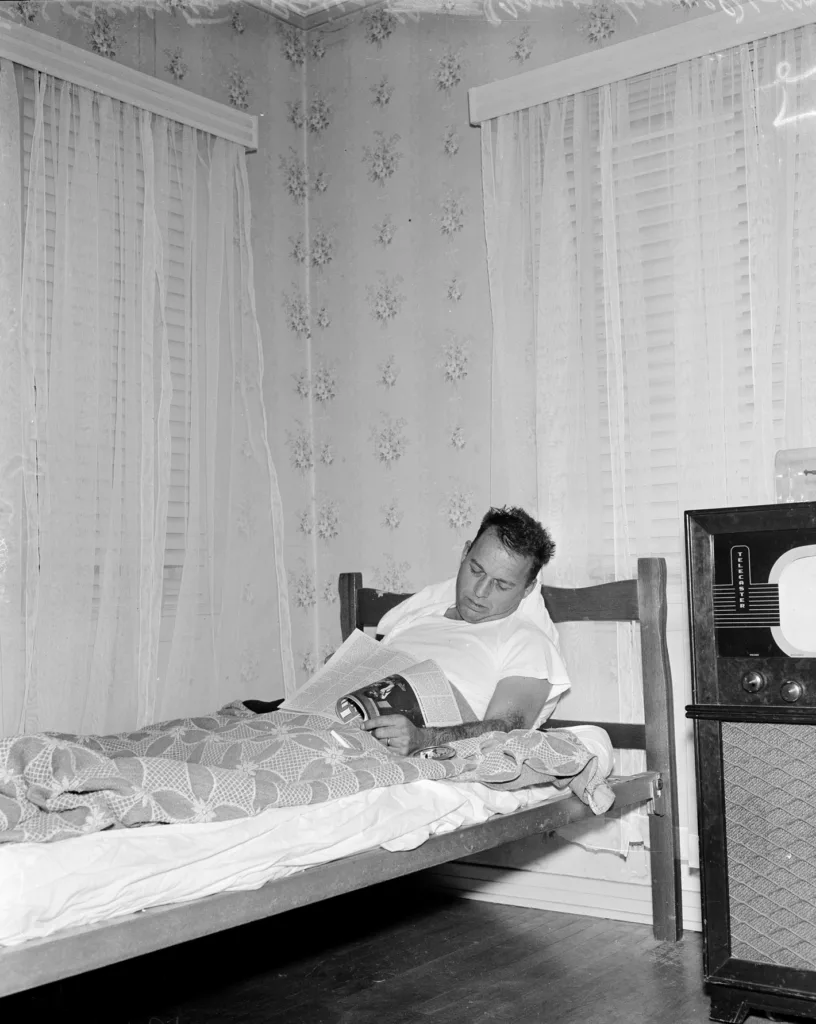

There’s an old film from 1961 or 1962 about the Bel Air fire. It’s only 26 minutes long, and the truth is, it’s a little bit damning in terms of how little we’ve done since then. With the exception of the shake roofs, you could run that 26-minute video right after footage of the Altadena and Palisades fires and see uncanny similarities. So what has prevented us from adapting? Fire risk might be new in its scope, but it is not a new issue. We’ve known about it for a long time, and we’ve failed to adapt.

Arthi

I’m coming from the perspective of the city’s long-range planning efforts: we set our goals for 2040. We view all of the regulations and policies that we implement today as incremental steps to get us toward our larger goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to a shifting climate. We’ve evolved so much as a society, and we tend to think of that as progress in so many ways—and it is. But when I consider land use and development patterns, I certainly think we can take some lessons from how we used to plan around the streetcar in Los Angeles, and how that changed with the advent of the car and completely shifted our development patterns. Planners today are trying to go back to that, looking at those early models of transit planning, before communities had wide

access to cars. These are many of the things we’re addressing in our Mobility Plan.

We also have a strong office of historic resources. Margot, you mentioned all of these toxic materials that are being used today, like vinyl windows. We’re able to incentivize protecting older buildings that may actually have more sustainable materials. We have a new Adaptive Reuse Ordinance, a 2.0 version; I know folks who are on this call were key in supporting that effort. Finally, as technology and engineering methods have evolved over the years, we’ve developed areas of the city that we couldn’t develop 70 years ago. Even in more sensitive environmental areas, we can now grade in a hillside and make a stable slope suitable for building. While I think there may be a lot of opportunities there, we need to find ways to balance that with a more ecological perspective.

Margot

Since I’ve taught at Cal Poly for 20 years and been the department head there for another 10 years, I’d love to discuss the role of education. Arthi just mentioned historic preservation and adaptive reuse—these topics are rarely taught in most schools of architecture, at least in terms of the theory and the practice. We do look at reuse of buildings, but it’s not always in a grounded and systematic manner. I think that’s an area where we as educators can contribute, but the curriculum hasn’t kept up to integrate these topics. Practitioners in the field are looking for graduates who have greater awareness of how to meet these design challenges in the built environment—past, present, and future.

In some areas we have concurrence, and in other areas we have conflicts. Think about daylighting—maximizing the use of natural light to illuminate indoor spaces. This is a major architectural feature both from a solar perspective and from an energy conservation perspective, as well as benefits to human health and well-being. But vulnerabilities to fire are directly linked to the fire-resistivity of the building envelope that includes all components—roofs, walls, windows, skylights, and so on. This makes the educational aspect especially interesting to me—helping the current generation, as they go out into the workforce, gain the knowledge they need to think holistically about these questions of design, planning, and construction.

Michael

Given that this conversation is for Harvard Design Magazine, for a school, I think Margot’s comments about education should be what concludes our conversation. One of the things that strikes me here—and that has struck me in many discussions over the three months since these fires—is the depth and breadth of knowledge about these issues, as well as how many ideas, techniques, and technologies are out there that would be extremely useful if they were implemented. It seems to me that one of our biggest challenges is not so much a lack of resources but rather insufficient ambition to pursue and implement those ideas. We need to push ourselves beyond the search for simple singular issues or singular culprits in these stories.

It’s important to embrace complexity and sometimes conflicting, or seemingly conflicting, ideas. Consider, for instance, questions around regulations; if you look at urban fires from the late 19th century or early 20th century, they were transformational. New York is a great example of a city that completely changed its approach to building after major fires, which ultimately strengthened its ability to create a denser urban fabric—for the positive—due to the regulations placed on construction and the incentives for developers to follow those regulations. At the same time, it’s also important to minimize the impediments and challenges around the regulatory laws that restrict how quickly and flexibly we can build.

This is an opportunity to rapidly test and implement many ideas, drawing on the knowledge of the design professions—architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, and engineering. We should seize this moment to apply these often historical ideas, reframed in contemporary ways, as flexibly and openly as possible. That is one way that rebuilding these communities, as well as building in the future, can become the tangible proof on the ground that Dana described. You could point to the rebuilding in Pacific Palisades or Altadena and say, “these are extremely useful examples of how we go forward.”

Hawthorne is senior critic, Yale School of Architecture, former Los Angeles Times architecture critic, and former city of Los Angeles chief design officer.