Temporary and Tactical: Ephemeral Structures for Public Space

A shading pavilion in the park. A pop-up chapel in a parking lot. A pollinator tower in a plaza. These architectural interventions differ in material, form, and scale, yet they share a common purpose: to strengthen community, advance equity, and address climate change. Envisioned as neither permanent nor precious, these ephemeral structures aim for economy and replicability. Their components are designed to be easily sourced and assembled, and their footprint remains light—both literally and environmentally. Notably, Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) faculty and alumni are at the forefront of developing and realizing these adaptable prototypes.

A few months into the pandemic, the empty streets and padlocked parks of Cambridge, Massachusetts, sparked an idea for Iman Fayyad (MArch ’16), assistant professor of architecture at the GSD. Instead of limiting public access, she wondered, could design be used to bring people together safely? After all, no one knew how long COVID-induced isolation would last. Fayyad reached out to the Cambridge Community Development Department (CDD) to gauge the city’s interest in such an idea. They responded with a proposal of their own.

Cambridge was in the midst of shaping the Healthy Forest, Healthy City initiative, a multifaceted approach to expand the city’s tree population in order to reduce summer heat, improve air quality, and support biodiversity. Foundational studies led by the firm of Reed Hilderbrand revealed that tree cover in Cambridge was, in fact, an equity issue: the sparsest canopies were found in neighborhoods home to at-risk populations—lower-incomes residents, communities of color, older adults, non-native English speakers. Determined to address this imbalance, the city committed to long-term programs of tree planting and cultivation. But trees take time to grow, and urban heat islands were intensifying quickly. Cambridge needed a short-term intervention—and fast. So they turned to Fayyad with a simple but urgent request: make shade.

Initially, Fayyad and the CDD envisioned a shade structure that was modular, replicable, cost effective, and easy to fabricate, assemble, and disassemble—without the need for specialized tools or contracted labor. Fayyad began by considering materials: what could she use that was accessible, affordable, and adaptable amid COVID’s supply chain disruptions and inflated prices? Plastic—specifically, four-by-eight-foot sheets of high-density polyethylene (HDPE)—had become ubiquitous in hospitals and commercial spaces as protective barriers. The question then became how to transform these flat, rectangular sheets into a self-supporting, minimal-waste structure.

Since her time as a GSD student nearly a decade earlier, Fayyad had been exploring curved crease folding—an origami-inspired technique for shaping flat materials into three-dimensional forms. The HDPE sheets offered a chance to apply this geometric method at an architectural scale.

In collaboration with four GSD students, Fayyad installed the resulting pavilion—CloudHouse—in Greene Rose Heritage Park in mid-Cambridge.1 For more than a year, CloudHouse provided shade and shelter to the neighborhood’s diverse community, creating a shared refuge for local schoolchildren, nearby housing residents, and young Kendall Square professionals alike. The project catalyzed Fayyad’s ongoing research into what she describes as “the development of new formal, geometric, structural languages from the idea of producing no, or reduced, waste.”

A subsequent project, In the Round—a plywood seating and gathering enclosure showcased at the Chicago Architecture Biennial—demonstrates the evolution of her curved crease folding technique. Meanwhile, CloudHouse itself became a prototype for a broader city initiative. Its success inspired a series of temporary shade structures across Cambridge, paving the way for the city’s Shade is Social Justice program, which invites designers to test creative, modular approaches to mitigating urban heat islands and advancing environmental equity.

Several GSD alumni have contributed to Shade is Social Justice installations, including Carolina Aragon (MLA ’04), Matthew Okazaki (MArch ’18), Will Adams (MArch ’18), and David De Celis (MArch ’98). Among the most illustrative examples is Growing Shade, a flexible zone in Cambridge’s Russell Park designed by Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio (MArch ’23), who worked with members of a local Bangladeshi immigrant community to envision the space. The project features a gauzy, double-layer canopy draped across wooden stakes that also support sapling trees. Arranged in a circular gradient that traces the sun’s rotation, the indigenous trees will, once mature, render the original installation obsolete as their living canopies take over the work of providing shade.

Like Fayyad’s CloudHouse, Growing Shade is intentionally temporary. Its component parts—two-by-fours and cinder blocks, easily soured from a hardware store—can be disassembled and reused in other parks. “Building a permanent space is a bureaucratic process and takes a very long time; it’s just the reality of the built realm,” Saldarriaga notes. “In contrast, these interventions are often more feasible to do.” In this case, the ephemeral installation anticipated a more permanent intervention, illustrating how experimental design can seed long-term transformation in the public realm.

Growing Shade was not Saldarriaga’s first foray into ephemeral design—a mode he prefers to describe as anti-permanent or semi-temporary, emphasizing life cycle over temporal duration. This mindset proved especially resonant during the pandemic, when he designed Alhambra’s Cross, an open-air chapel for a senior group’s Easter services in Saldarriaga’s home city of Bogatá. In collaboration with German Bahamon and the Colombian Society of Architects, he designed a Greek cross from horizontal concrete-casting formwork—loaned free of charge from a construction supplier—that could be easily assembled and removed. For four days, a parking lot became a sacred space, offering celebration and safety to a vulnerable community amid a global crisis.

Over the past three summers in Indianapolis, Indiana, another ephemeral installation has reclaimed space once devoted to automobile traffic for community use. Conceived by Nina Chase (MLA ’12) and Chris Merritt (MLA ’17) of Merritt Chase and Big Car with the City of Indianapolis, Monument Circle Park—also known as SPARK on the Circle—transforms one quadrant of the rotary surrounding the Soldiers and Sailors Monument into a vibrant civic commons. Lush greenery and plantings turn the area into shaded, garden-like spaces for play, rest, and gathering—bringing new life to the heart of downtown Indianapolis from June through September. As part of the city’s larger resiliency strategy, the pop-up park demonstrates how design can reconnect people to shared public space. Beyond serving as a community attraction, it also stands as a form of advocacy, showcasing the social, economic, and environmental value of investing in human-centered design.

Monument Circle Park builds upon an earlier project by Chase, Kit of Parks—an award-winning portable system she developed before co-founding Merritt Chase. Designed for quick deployment in underused areas, Kit of Parks embodies a philosophy of temporary placemaking that addresses social inequities through low-cost, scalable interventions. This approach to tactical urbanism seeks to create welcoming, community-oriented environments in places where resources are scarce.

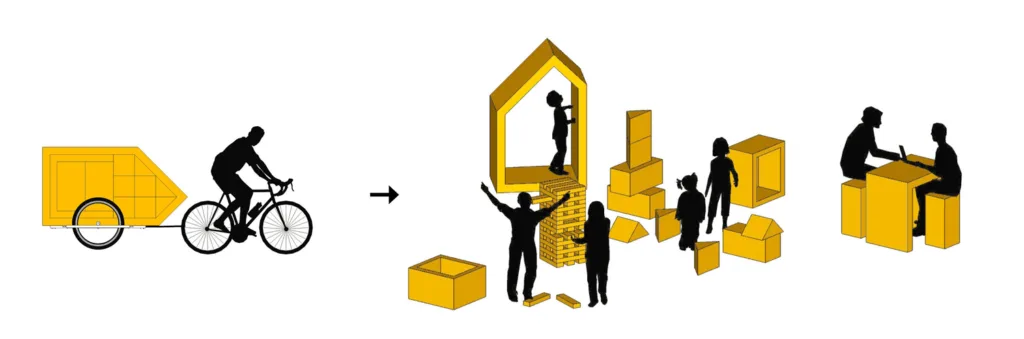

A similar ethos drives the work of Kounkuey Design Initiative (KDI), an international non-profit firm founded by Chelina Odbert (MUP ’07) and five other GSD alumni—Jennifer Toy (MLA/MUP ’07), Patrick Curran (MLA ’06), Kotchakorn Voraarkhom (MLA ’06), Ellen Schneider (MLA ’05), and Arthur Adeya (MLA ’06). KDI’s projects include Play Streets, an ongoing collaboration with the City of Los Angeles that helps residents periodically turn streets into shaded recreational areas using movable, KDI-designed components. The firm has also partnered with Angelenos and local organizations on Adopt-A-Lot, a pilot program that enables community groups to use a modular kit of parts to temporarily transform city-owned vacant lots into welcoming public spaces. Since 2020, four such lots have been activated—each a prototype for turning underutilized land into lasting neighborhood assets.

That same belief in modularity and shared public space finds a striking new expression in Polinature, a project that reimagines how strategic interventions can respond to heat, habitat, and human connection. Designed by the firm ecosistem urbano—co-founded by Belinda Tato—who is an associate professor in practice of landscape architecture, and Jose Luis Vallejo—Polinature features a tower of metal scaffolding supporting more than a thousand native plants and an inflatable canopy. The resulting pavilion, designed for replication in vulnerable communities worldwide, offers a space for both people and pollinators. Whether situated within a vegetation-starved city center, an arid landscape, or a vast parking lot, its responsive canopy adjusts to local conditions, providing shade, airflow, and data visualizations that help visitors understand their immediate environment.

With funding from Harvard University’s Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability and a GSD Design Innovation Grant, Tato, and Vallejo constructed the first Polinature protoype in a Cambridge backyard, where it remained for several weeks before being disassembled and redistributed—the project’s 1400 plants finding new homes across the city to enhance local biodiversity. Beyond its tangible environmental impact, Polinature also operates as a model of open collaboration: its technical drawings and modular system will be open-sourced, enabling others around the world to build their own versions. In this way, Polinature embodies the shared ambition at the heart of these ephemeral interventions—to connect communities, advance equity, and nurture a more livable planet.

- Former GSD students Rayshad Dorsey, Pietro Mendonça, Jack Raymond, and Audrey Watkins (all MArch ’23) worked with Fayyad on CloudHouse’s installation.