What’s in a Home: Reconsidering the Fundamentals of Housing

What is a home today? How do we reconcile our dire need for new housing with the fact that our needs will certainly change over time, and today’s buildings might soon be obsolete? How do we provide affordable housing that centers individuality and humanity? In this roundtable, three instructors at the Graduate School of Design (GSD) discuss their approaches to designing housing and homes—starting with their definitions of those terms. Each led an option studio at the GSD in the Fall 2025 semester focused on the question of housing in specific geographic contexts.

Farshid Moussavi, professor in practice of architecture, Stan Allen, design critic in architecture, and Toni L. Griffin, professor in practice of urban planning, describe their studios, which offer interdisciplinary perspectives and approach the question of housing at a variety of scales—the residence, the neighborhood, the city.

Griffin foregrounds the architectural and cultural history of Chicago’s South Side, where she has deep roots. Moussavi uses works in the Hudson Valley to help her students reimagine a Paris building through the lens of an ecology of care, while Allen guides students through the architectural diversity of Queens that has resulted, in part, from its diverse immigrant populations.

Rachel May

How do you define “home,” both personally and in your practices? Farshid, your course, “Housing as an Ecology of Care,” offered in tandem with your “Housing Matters” seminar, explores how humans and non-humans interact across their environments. How do you help students reconsider their conceptions of what home looks like today, and, therefore, what’s required of designers?

Farshid Moussavi

Home is less a kind of fixed object or typology, and more a condition of care and interdependence. It’s where architecture mediates relationships: between people, species, material, and temporal cycles. We need to think of home not so much as an enclosure but as an ecology: a space that evolves with those who inhabit it.

The contemporary concept of home extends beyond the domestic, encompassing professional, social, and environmental dimensions. That complexity demands design approaches that address not only individual comfort, but also collective resilience, adaptability, and non-human life, including planetary health and other species. At the same time, social care asks us to design homes that enable connection and mutual support.

The pandemic revealed that isolation is as much an architectural problem as a social one. We think about how spatial systems, such as shared kitchens or courtyards, or flexible walls, can enable collective life while respecting individuality. We’re seeing a profound shift from the nuclear household model to more fluid and collective forms of living, from multigenerational co-living, to live-work, and care-based arrangements.

Architecture can either resist or embrace these changes. We aim to design open-ended frameworks in which concepts such as family are spatially negotiable rather than predetermined. I want students to learn how every small decision they make connects to broader social, environmental, and cultural issues.

Rachel

Toni, your course is titled “Home. House. Housing.” How do you see the interrelationship between these terms?

Toni L. Griffin

I’m very interested in the narratives that land holds. I’m often asked to work in places where there has been some land trauma—urban renewal, foreclosure, vacancy, buildings that are underutilized or out of use. Repair and reclamation of land always show up in my work.

In the United States, our strategies are often heavily rooted in the dimension of housing, but not necessarily in dimensions of home. When we go back and look at the historic or even contemporary narratives of land, residents talk about concepts of home that aren’t always held within the structure of a house. However, designers are mostly talking about housing, which I define more as the policies, instruments, and mechanics of how a “house” is created, in various forms.

I was interested in having a conversation with a group of amazing students about the differences between home, house, and housing, and the fact that home does not necessarily need to live within a structure. It is very much relational or sensory, such that one’s neighborhood could actually be their home versus the house in which they grew up.

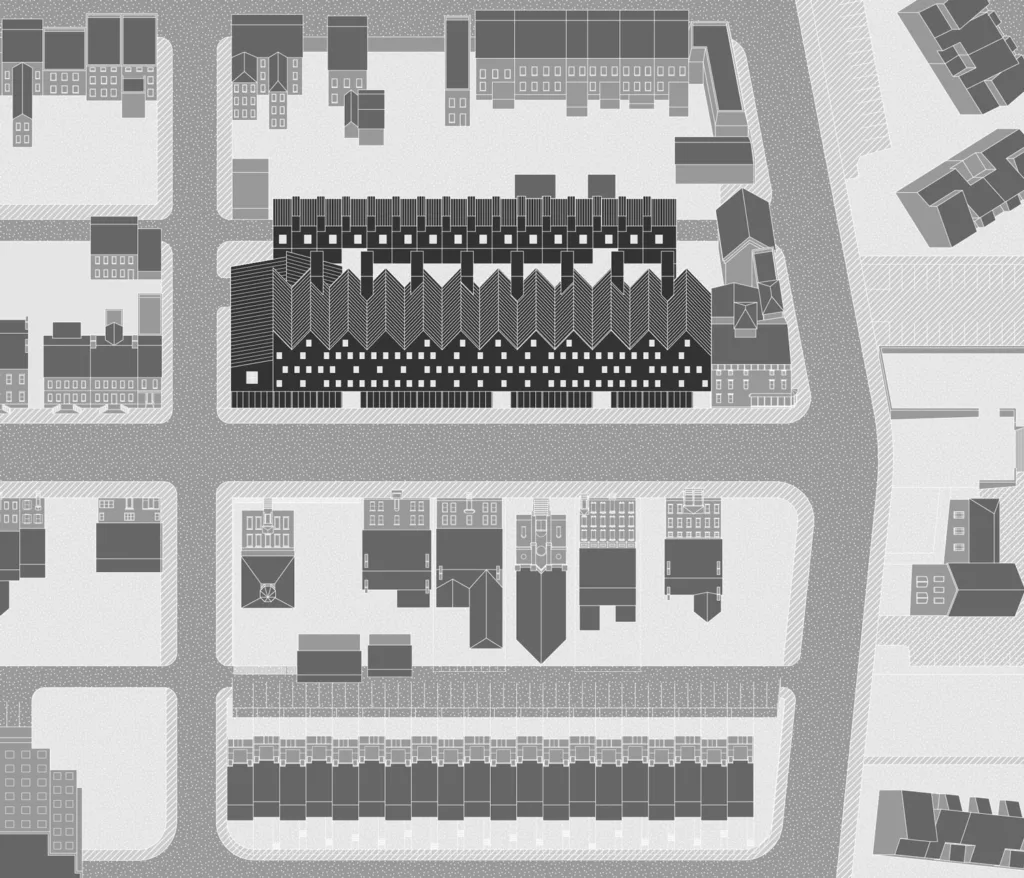

If we look at the way a “house” is produced, what drives the production of a house? If we look at floor plans—they haven’t really changed over time. In Chicago, the original floor plans of the typical three-flats and six-flats—buildings with either one or two apartments on each of their three stories—are not very different from the floor plans being produced today, a century later. So, we ask, are the systems and technologies that produce housing contributing to the stasis of what “house” looks like?

From the other perspective, as Farshid noted, what we need today relative to “home” is changing. If we just look back at the last five years, the way in which we occupied what we call “house” is changing. We tried to make home within the space of work, teaching, rest, or mental health care. Residential buildings and spaces attempted to hold many different things, many of which they were never designed for, as well as functions they perhaps should no longer hold at all.

I was very interested in each of those three concepts, how they were distinct, and how they informed one another. I wanted to see if we might be creating different forms of home, house, and housing—from the ephemeral, to the actual structure, to the mechanisms of how we produce it.

Rachel

Stan, in your studio “The House in the City,” how did your conception of the single-family housing unit translate to Queens, with its diverse architecture and multigenerational families?

Stan Allen

Like Farshid, I was very interested in looking at the individual house as a moment where a student can look very intensely at small-scale conditions of living and habitation, but at the same time, have a kind of obligation to the collective of the city and the space outside of the house. So, part of it has been training myself over the course of the studio to avoid defaulting to the term “single-family house.”

When you look at a borough like Queens, there are many intergenerational families living in houses. There is a predominance of double houses, which creates a very interesting relationship to the city and to your immediate neighbors. The demographics of the American family are changing. So, how can we think about the house as something that can accommodate different definitions of what a family can be in the 21st century?

In my studio we read a recent book by the Italian philosopher Emanuele Coccia, Philosophy of the Home. He talks about what happens when you move and your life is packed up in boxes. Your immediate family members, pets, house plants, books, furniture—that’s all as much part of home as the fixed architecture of the house. We’ve been trying to get the students to think about these issues, but in a context where they also have to think about their relationship to the block, the street, and the larger neighborhood beyond that.

Rachel

The South Side of Chicago holds a long history for Black residents and architects. Toni, how did that specific history impact the approaches you and your students took there during your studio trip?

Toni

On the first day of studio, I gave each student a little black notebook with about 20 prompts, which started with, “What is home?” We went through a quick charrette of defining these concepts individually. Students were asked to pull from their memories, expectations for the class, and interpretations of the studio prompt. That was my first way of encouraging them to think about scale—not just a spatial scale, but also as demography, memory, values, the interior of space—as well as where home, house, housing is situated in the context of the city.

We then learned the neighborhood we studied within the South Side. Students went through a series of exercises to learn the neighborhood’s historic and current contexts. And, as a multi-disciplinary studio, they share that learning from different disciplinary perspectives, which gave them a sense of different scales, as well as different cultural framings of place, home, and housing.

Rachel

Farshid, you are also interested in how scale relates to housing, describing this relationship as an “ecology of care.” Can you explain what that term means for you, and how your students design with that in mind?

Farshid

Calling the studio “Housing as an Ecology of Care” reflects an intention to think of scales as entangled, rather than as a linear progression from the individual unit to the block to the city, or vice versa. Each scale affects the other, even as each must also be addressed in its own right. In the studio, we explored this through projects that balance autonomy and togetherness, where the home becomes a node within a network of care extending to the neighborhood, the city, and the planet.

Designing homes today means designing the conditions for care, change, and coexistence. A home is not simply a shelter but a structure that allows life, in all its human and nonhuman forms, to unfold over time. It’s a living system, not a finished product.

To guide students, we asked them to consider four types of care. Historical care asks how interventions within a single floor plate or the structure of an existing building can reveal or reinterpret the city’s memory. Planetary care examines how elements such as a roof garden, terrace, or material choice connects to broader ecological cycles. Social care focuses on how the configuration of an individual unit can foster collective life. Temporal care challenges students to think about the long life of a building and how it might evolve alongside the city.

We also study precedents. For example, the work of Renée Gailhoustet and Jean Renaudie in France offers compelling examples of housing design that blurs the boundaries between the individual unit, the block, and the city. There is a ripple effect across scales that ultimately transforms housing into an ecological project.

Stan

Before choosing a site, I ask students to design first to a series of zoning regulations, in this case from New York City. In addition, to accommodate a family of their own definition, they had to include an additional element that came from that narrative—a shared workspace or commercial space or rental apartment. So, within the framework of the house, you have a certain degree of complexity, and the need to accommodate strangers and outsiders within the so-called “private” house.

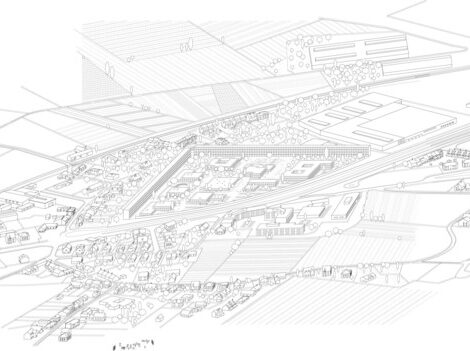

From there, we visited Queens and spent three weeks collecting information and doing analysis. Some students took the initiative to return to New York and learned more about the complexity, architectural richness, and diversity of Queens.

Rachel

Queens is undergoing a great deal of change right now, with rezoning intended to provide more than 14,000 housing units in the borough. Put this in the context of the borough’s history. What patterns of development continue to shape Queens?

Stan

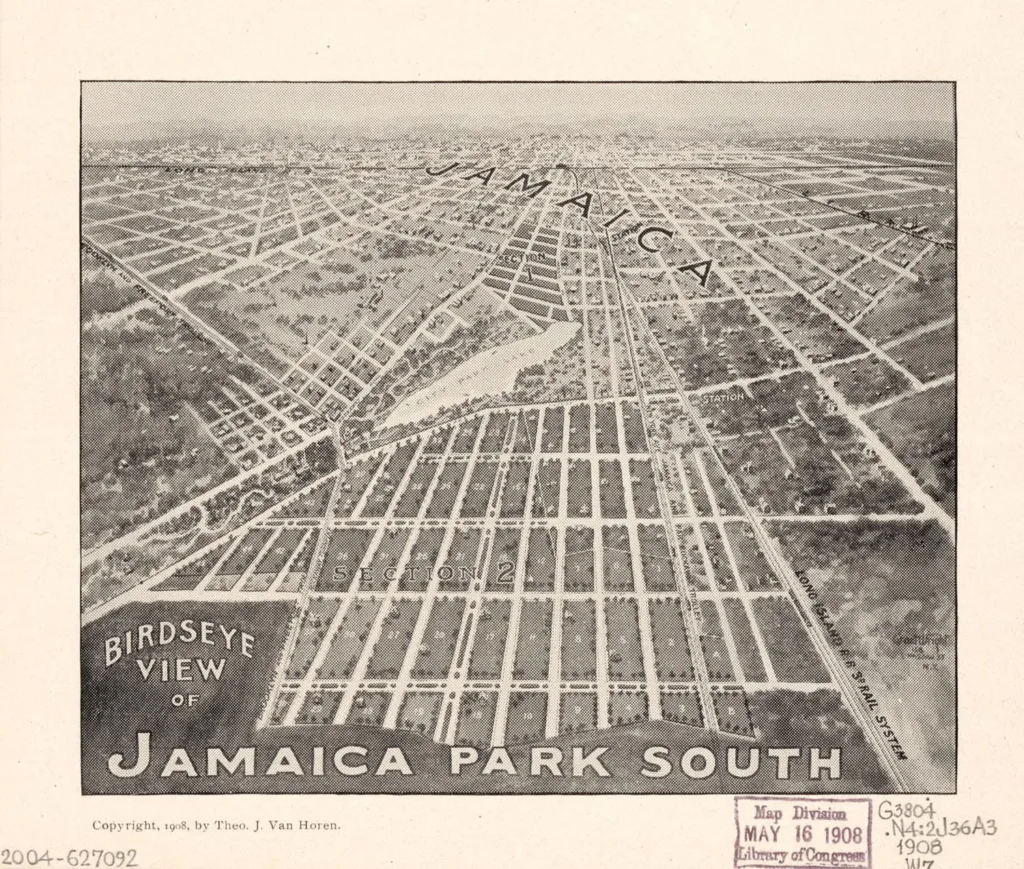

The five boroughs of New York City were amalgamated in 1898. One of the maps that the students found was from around 1840. You can see that Manhattan is very much urbanized. Brooklyn is urbanized. Queens is still a network of villages linked together by roads. You wouldn’t call it rural, but it’s lower density, and more scattered.

Every borough in New York has a single postal code, except for Queens, which has seven. Elmhurst, Astoria, Flushing and so on, have linkages back to the original villages of Queens. At 109 square miles, it’s the largest borough in terms of area. Today, it’s the most demographically diverse. Successive waves of immigration and a strong sense of identification with the neighborhood, are, in turn, reflected both in the development history and the block structure.

Much of Queens was developed by builders who bought large parcels, divided them up into blocks, and built all at once. This means that the blocks are very consistent at the level of architectural structure itself, the typological structure. The individual houses are quite similar, but over time they’ve been differentiated through additions, decorations, and gardens. Gardens are very important in Queens. So, you have this astonishing model of a very high degree of differentiation of individual houses, yet a kind of consistency and coherency of the block structure, which I had never really encountered before.

Rachel

Toni, your site is also set in an urban neighborhood that’s seen a lot of demographic changes over time. Can you talk about your relationship to the South Side? Why you chose that site, and how you see it changing today?

Toni

I am a Chicago South Sider. My whole family still lives in the city. My dad grew up in the studio study area, Washington Park, and I have been working there off and on for the last five or six years, first with the Obama Foundation, when they were in the site selection phases for the Obama Presidential Center. During that time, the Obama Foundation, the University of Chicago, and Mayor Rahm Emanuel created a new neighborhood economic development organization. I later went on to help build that organization’s strategic plan and have been doing work in the neighborhood to create a more progressive reparative agenda around land and home ownership, by looking at a neighborhood-scale real estate investment trust. It’s very complicated and a fairly elaborate way of deepening ownership and wealth-building options for current, legacy, and future residents. The aim is to lessen their vulnerabilities as the neighborhood changes and grows.

I also wanted to invest back in my hometown and my dad’s neighborhood. So, I just bought a two-flat home, built in 1890, in the heart of the neighborhood, which the students visited during our studio trip. I’ve been thinking about what it means to both invest back into a place where I spent the first few years of my life—where my family’s history is and where I’ve been working on a reparative agenda—and what it means to really be vested in the place where I work.

This neighborhood sits within what was historically known as the Black Belt, where African Americans, through both waves of the Great Migration from 1910 to 1940, moved from the rural agrarian and Jim Crow south to the industrial North. While Jim Crow was not the legal law of the land in the North, real estate and public policy practices certainly reinforced the discriminatory tenets of Jim Crow. So, African Americans were forced to live in a very segregated area of the city, just south of downtown, near the stockyards.

Blacks first lived in tenements. As those tenements began to erode, periods of urban renewal started. Racial covenants and discriminatory real estate practices both restricted incoming African Americans and imparted fear on whites who lived in the area, and they fled. Other practices, like overpricing housing, took advantage of African American families trying to move in. All of this was steeped in a continuous flow and flux of populations, Black and white, moving in and out.

But, my dad tells the story of the six-flat that he grew up in, that had this palatial recessed balcony. He remembers, as a kid, going out and looking over the street and playing. I hope students learn the importance of discovering the complexity of land narratives across a neighborhood’s history and periods of change.

Rachel

Farshid, your studio focused on the repurposing of an office building in Paris designed by Ricardo Bofill. Yet, you also took them to the Hudson Valley to study two other examples: Dia:Beacon, a repurposed industrial building that is now an art center, and Manitoga, the home and studio of industrial designer Russel Wright. What is the relationship between these different sites and how do they contribute to the notion of a house you wanted to explore?

Farshid

We began with an existing Parisian office block, asking students to design simultaneously at the scale of the existing structure, apartment, and neighborhood interface. Working within a pre-existing frame teaches them that housing is always in dialogue with what came before: materially, socially, and spatially. We asked: if you change the section of a single unit, how does that affect the courtyard? If you introduce shared space on a floor, how does that transform circulation, light, and public life at the ground level? By diagramming these relationships, students started to understand the ripple effects of their design decisions.

The connection to Manitoga and Dia:Beacon isn’t geographic, but conceptual. Both embody the central question of the studio: how can architecture express care—for history, the planet, community, and time—through transformation, rather than replacement? They serve as case studies in care and adaptive reuse, offering different ways of working with what already exists, which directly informs the Paris project.

In Beacon, we studied an industrial building that was transformed into a space for art and collective experience—an example of architectural and planetary stewardship. Manitoga, by contrast, operates at the scale of landscape, showing how living in a place can be inseparable from an environment in constant change. Once a quarry, Russel Wright adapted the site into his home through both intimate decisions about daily life and large-scale interventions in the land itself. It’s a beautiful and powerful example of designing at a moment within a much longer temporal continuum.

Together, these sites offered students an attitude towards ecology and care that could not be learned solely from the Bofill building in Paris.

Rachel

As all of your studios foregrounded issues around sustainability and planning for future climate and societal changes, how did you think about materials, and guide students to design for an unpredictable horizon?

Farshid

The Paris site already contains a wealth of material resources, for example, non-operable glazing and glass from windows that no longer meet contemporary needs. Students can reuse this material within the block or rethink existing floor plates that are too deep for new housing. In the studio, we treated materials not just as technical choices but as ethical and ecological ones. We asked: what histories, forms of labor, and possible futures are embedded in a material? At the building scale, this means valuing what already exists, and seeing the structural frame, for instance, as both a construction system and a form of memory.

At the city scale, material decisions become part of an urban metabolism: how resources circulate, how waste is reduced, how care extends beyond a single site. At the global scale, the focus shifts to regenerative systems, by choosing materials that can be renewed, disassembled, or ultimately returned to the earth. Sustainability, in this sense, isn’t just about efficiency, but about cultivating long-term relationships between matter, people, and the planet.

A key question we pose is how to design systems of assembly that can be demounted in the future, so that buildings are not simply demolished when they become obsolete. Bio- and geo-sourced materials are part of that conversation, but it’s equally important to think about recyclability and reversible systems of construction. Designing for an unpredictable horizon means designing so that others can adapt, reuse, and care for what we build long after we are gone.

Rachel

Toni and Stan, you’re both navigating zoning regulations that impact new construction. How has that affected how you think about the typologies and scales of the South Side and Queens, respectively?

Toni

Our studio’s investigation of new forms of home/house/housing inherently requires a disruption of the building codes and zoning requirements that don’t allow us to build, which Stan discussed. So, we look at everything from how a building is sited, how many buildings can be sited, the size of the parcel, setback heights, as well as the materiality, fenestration, light, air—all of those are things that we’re asking our students to take up.

Students are looking at adaptive reuse of some of the existing buildings—brownstones, greystones, two-flats, and three-flats that remain in the neighborhood. Some of our creative muses, like Theaster Gates from the Land School and Rebuild Foundation, and Amy Ginsburg, who founded the Narrow Bridge Arts Club, inspired the students through their approaches to adaptive reuse. One institution is an old synagogue; one is in an old school. Amy talked about how the arts club deploys embodied inheritance and maximizing flexibility.

We also had an amazing lecture by Lee Bey, the architecture critic of the Chicago Sun-Times. His book Southern Exposure documents the extraordinary inventory of mid-century modernist architecture on the South Side, a lot of which was designed by African Americans, such as John Moutoussamy, at a time when African Americans were very much shut out of mainstream commissions.

Stan

Queens is a place of infrastructure. New York City’s two major airports are in Queens. There’s a relatively small amount of green space in Queens. All of the City’s major cemeteries are in Queens. What I thought was an urban legend, turns out to be true: there are more people buried in Queens than live in Queens. This speaks to the idea that Queens is the place where a lot of the functions that Manhattan didn’t want ended up. It was seen for a long time as marginal, and this presents new opportunities.

There are important moments of collective housing in Queens, particularly the recent development along the East River, where it’s starting to look like Vancouver with so many new condos. We weren’t particularly interested in that. Some of the older areas were more interesting to us—Sunnyside Gardens and Jackson Heights, for example, have a history of innovative early housing types. That’s all available in Queens. There’s a level at which the diversity of the city is right there on the surface. One student is working in Long Island City, where there’s still a tradition of light manufacturing. She has incorporated an auto body shop into the confines of a private house, dealing with something at a small industrial scale within the confines of the domestic space.

I mentioned the importance of the gardens in Queens, which tend to be in the front of the building, not in the back. Many of those gardens are not decorative gardens. Chinese Americans are growing the vegetables that they’re using in their everyday cooking, in the space between the sidewalk and the front door. So, you walk down the street and see peppers and melons. The students are learning from the collective creativity of the city itself.

Rachel

If you were to bring your classes together, what are some of the conversations that you hope they would have? What do you hope your students will carry with them after the courses end?

Toni

What does it mean to create neighborhoods that hold populations that live and/or work and/or play and/or learn in the same space? What are the arrangements of blocks and lot sizes and streets and pedestrian ways that can best facilitate a greater diversity of housing types, for a greater diversity of populations whose needs are changing relative to what they need in this artifact called a house?

Farshid

I hope students leave thinking about housing not as a fixed typology, but as a living system of relationships, between people, histories, and ecologies. Even the smallest design decisions have significant consequences for how we engage with one another, how we shape our neighborhoods, and how we transform our planet, for the better and worse.

It is essential to keep these different scales in mind and to recognize the power architects hold—and the responsibility to use that power wisely.