Toward an Architecture of Comfort: Jenny French on Climate, Clothing, and Collectivity

What if architecture behaved more like clothing—a soft, flexible system that can be layered, adjusted, and reworked in response to weather or need? This proposition animates “Outfitting Architecture: Expanded Comfort in Athens,” a fall 2025 studio at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) taught by architect and educator Jenny French. Treating building envelopes as garments reframes questions of social and thermal comfort, unsettling familiar assumptions about how people and structures should behave. The studio extends a broader inquiry French shares with her sister, Anda: through their Boston-based practice, French 2D, they draw on domestic material culture—from clothing and everyday objects to collective housing—to consider how space shapes, and is shaped by, the human relationships it hosts.

Describing the stakes of “Outfitting Architecture,” which was funded by Harvard’s Center for Green Buildings and Cities and Joint Center for Housing Studies, French situates the studio squarely within the climate emergency. “How can we give material structures more agency to negotiate the dynamics of increasing temperatures, energy usage, and pending crises,” she asks, “and importantly, for prosocial ends?” Athens, with its ubiquitous polykatoikia, offers a testing ground for such investigations.

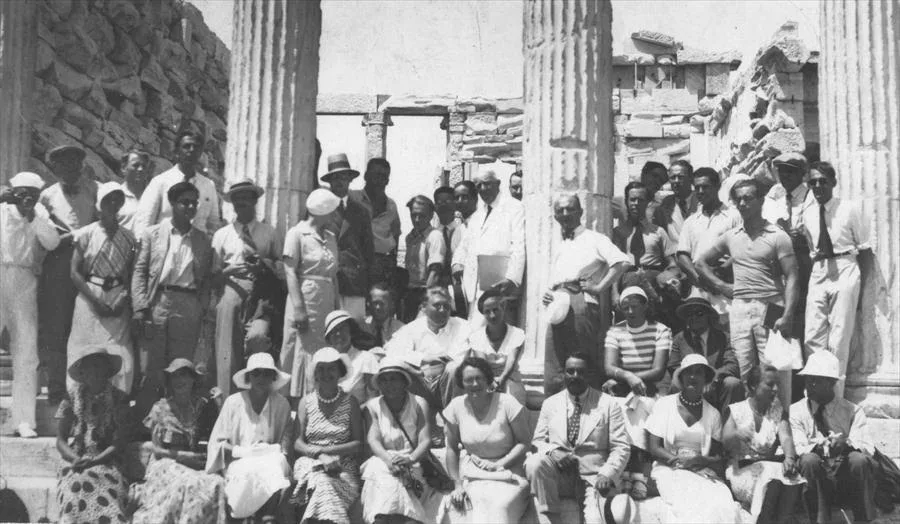

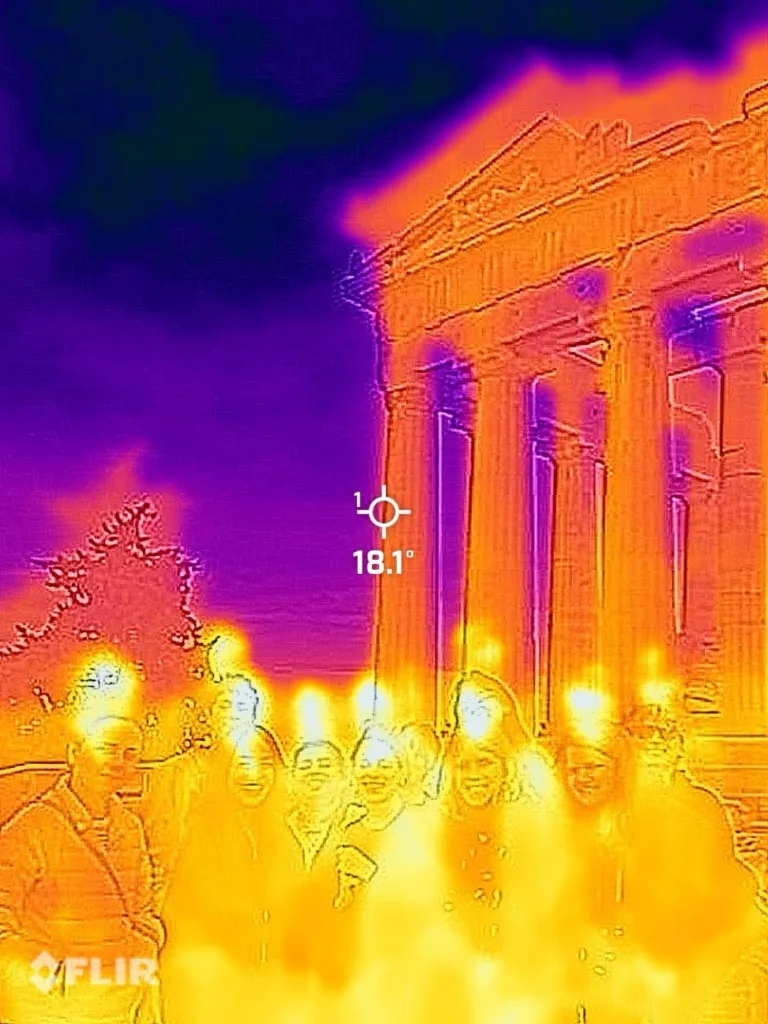

Often described as Europe’s hottest capital, Athens grew rapidly—and largely without coordination—in the mid-twentieth century, driven by post–World War II reconstruction and the demand for housing. Multistory reinforced-concrete apartment buildings, the polykatoikia, proliferated, extending modernist logic into a dense, improvised urbanism that left little room for trees. The result is a city of tightly packed thermal mass: concrete, asphalt, and exposed roofs that absorb heat by day and release it slowly by night, intensifying the urban heat island. In many buildings, awnings provide some relief, but not enough to offset limited airflow and lingering heat—conditions that have become severe enough that, in extreme summer temperatures, the Acropolis now closes for human safety.

In that sense, Athens—increasingly hot and short on shade—offers a preview of what other dense urban areas may soon confront. For French, this combination of rising temperatures and sparse tree canopy makes the city an attractive testing ground. The polykatoikia is especially instructive because it typically includes balconies, which French describes as “intermediary spaces between the absolute interior and street life where shading devices, the spillover of life, and porosity are already on display.” In “Outfitting Architecture,” students treat that intermediary zone as the project’s leverage point, adapting an existing housing type with thermal comfort as the primary driver. The aim, French argues, is to imagine a secondary envelope whose performance moves beyond insulation alone—one that carries cultural and social meaning and connects to the life that already unfolds in these in-between spaces.

There exists a rich theoretical discourse linking architecture and clothing. In White Walls, Designer Dresses, Mark Wigley reframes the seeming neutral white wall in modern architecture as a deliberate garment—aligned with contemporaneous clothing reform—meant to disclose the architectural body’s “true” form. Likewise, in works like Surrounding Islands (Biscayne Bay, Miami, Florida, 1983) and Wrapped Reichstag (Berlin, Germany, 1995) artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude deploy fabric to recast how embodied meaning and aesthetic experience are produced. French’s pedagogical and design explorations extend this lineage but redirect it from symbol and spectacle toward use: what architecture can do when conceived as clothing, how it layers, vents, insulates, and moves with bodies over time. Here the wardrobe becomes an environmental toolkit, where adjustable thresholds and everyday practices fine-tune comfort, and meaning and performance converge.

This research is part of a broader effort within the GSD’s Department of Architecture to address the realities of climate disruption. “For designers today, it is critically important to understand the impact of our changing climate, and the department is very focused on cultivating students’ design instincts to face these predicaments,” said Grace La, Professor of Architecture and Chair of the department. “Jenny’s studio produced innovative ideas on how to adapt to existing structures, and we are very excited about its results.”

The Athens studio is not an isolated experiment, but the latest iteration of a teaching agenda French has been developing for years. Across earlier housing studios, she has used “architecture-as-clothing” as both method and metaphor, asking students to understand comfort as something created through the strategic use of thresholds and routines rather than sealed interiors. Projects have ranged from a building that toggles between cold storage and housing to studies that look to performance outerwear (think Patagonia) for cues about how materials, assemblies, and habits shape what bodies can do, and how they live.

Beyond studio pedagogy, French’s broader project turns insistently to material culture—those domestic things that sit adjacent to architecture but rarely count as it: textiles, clothing, the body as subject. This threads through Bay State Cohousing (2023), a 30-unit multigenerational community in Malden, Massachusetts, that French 2D guided from concept through completion, working alongside future residents to shape individual apartments and shared spaces. Even in Boston’s cold climate, she notes, the project’s priorities focus on year-round outdoor and in-between spaces—thresholds that foster social ties. In Dinner Cozy, French 2D translates that interest into an exaggerated instrument of conviviality: a 40-foot octopus-like tablecloth made from striped fabric backed with thermal-blanket material, capable of gathering—and warming—nearly 30 people outdoors, while gently scrambling the codes of etiquette. The same vivid gradient textile appears in Cozy Wall/Wall Cozy, which redresses a concrete corridor in the GSD’s Gund Hall, turning the institutional hallway into something more like a soft half-room, where chairs become enveloping entities for occupation, and comfort is framed as both sensation and social arrangement.

The striped textile reappears in House Jacket, a building model cloaked in insulating layers—long johns and a puffer coat, translated into architecture. That logic of model-as-mannequin and layering-for-performance also structured the Athens studio: students built oversized representations of polykatoikia and “dressed” them, demonstrating their design interventions. As French explains, “Outfitting” names a thought experiment that goes beyond recladding a facade toward “re-dressing” it—literally with a new protective layer, and figuratively by correcting its thermal underperformance that earlier climates could afford to ignore.

Redressing can, of course, take on more than thermal performance. When French 2D was commissioned to create a facade for an open-air garage in Kendall Square, they wrapped the structure in a large scrim, whose scalable pattern mediates the building’s position between a residential neighborhood and a booming technology hub. Installed as a mesh facade system, the shadow-play graphics give the garage a double legibility: as both a porous screen and a single, coherent object. To underscore the link to material culture, French and her sister also fabricated—and wore—bright dresses printed with the same pattern, documenting their movement through the structure. The garments extend the garage’s graphic language while retaining their own autonomy.

That Kendall Square project clarifies French’s larger premise: dressing a building moves beyond the mere cosmetic, recalibrating how it performs, reads, and is inhabited. The scrim—and matching dresses—collapse the distance between facade and garment, object and body. The Athens studio pushes the same logic into the domain of climate, asking what it would mean to treat an entire housing type as something to be outfitted rather than sealed.“Outfitting Architecture” envisions building envelopes as a form of adaptive, climate-response outerwear, so the polykatoikia becomes something you dress rather than hermetically seal. The implications are more than operational: performance becomes tactile and design begins to resemble wardrobe-making—attentive to bodies, habits, and weather. French 2D’s oeuvre offers a parallel proof of concept, proposing architectures that can be revised and reimagined without insisting on permanence. Together, French’s teaching and practice suggest that in a warming world, the most resilient buildings may be those that, like clothes, can be continually adjusted—making performance a social practice as much as an environmental one.