An Interview with Eric Höweler: AquaPraça, from Venice to Belém

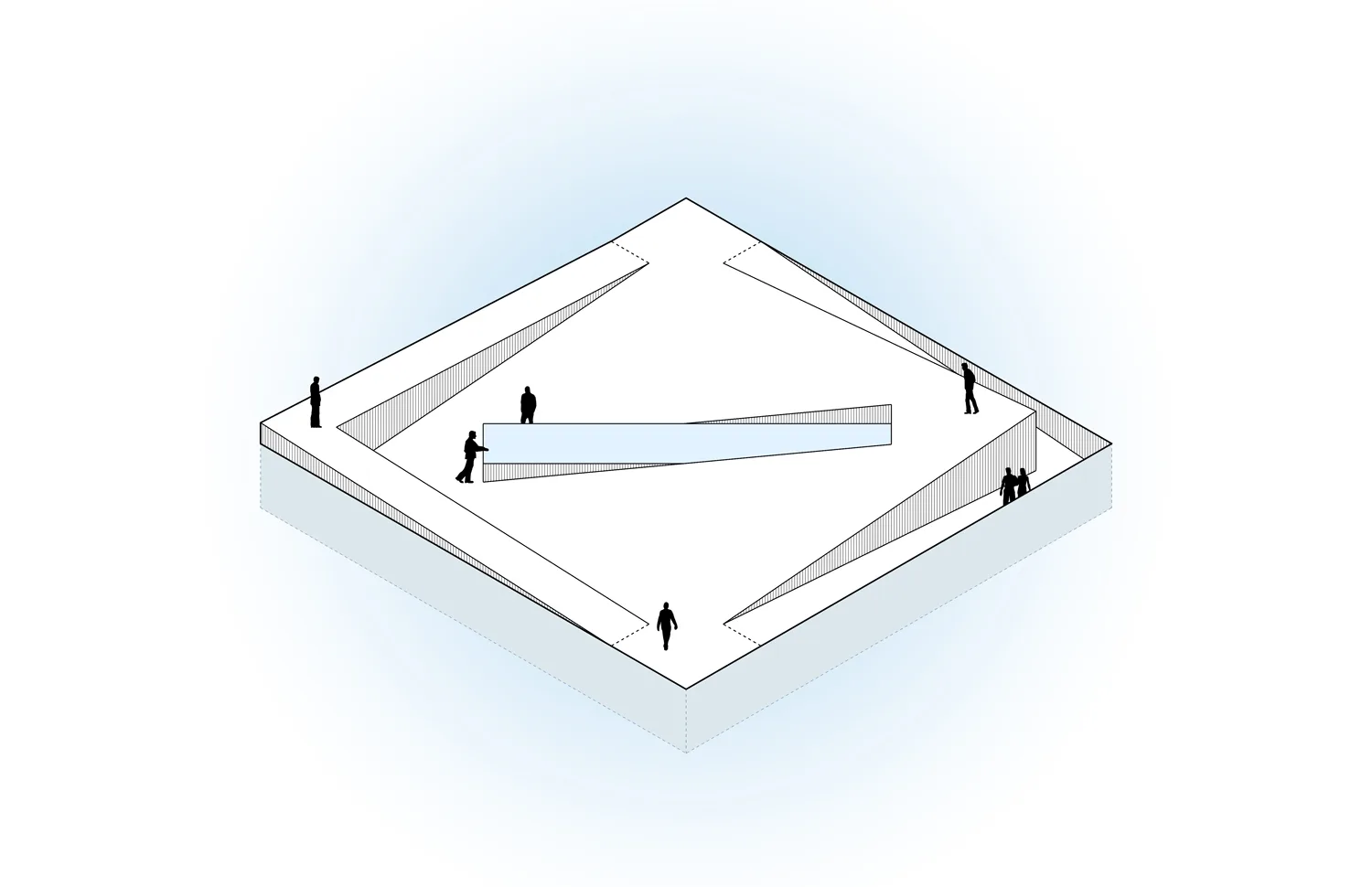

On a late summer day, AquaPraça—a floating 400-square-meter steel platform, painted brilliant white—appeared in the Venetian Lagoon, destined for its September 5 debut at the 19th International Architecture Exhibition at La Biennale di Venezia.

While seafaring vessels are commonplace in this historic maritime city, AquaPraça is far from routine. This waterborne cultural plaza (AquaPraça is Portuguese for water square) can accommodate over 150 people for events, workshops, and gatherings. Incorporating principles of displacement, buoyancy, and equilibrium alongside sensing technologies, the submersible positions visitors at eye level with the water, highlighting the reality of our rising seas and the global impacts of climate change.

Höweler + Yoon (founded by GSD professor Eric Höweler and alumna J. Meejin Yoon [MAUD ‘02]) and CRA–Carlo Ratti Associati (led by Carlo Ratti, curator of the most recent Venice Architecture Biennale) conceived the floating venue for the world-renowned exhibition, yet Venice is only its first stop. Soon AquaPraça will embark on a transatlantic journey to the port city of Belém, Brazil, where it will serve as an Italian contribution to the UN Climate Change Conference (COP30).

Shortly after AquaPraça arrived in Venice, the GSD’s A. Krista Sykes spoke with Professor Eric Höweler about the project’s design, fabrication, and afterlife; the ability of architecture to promote eco-literacy; and what responsible architecture might mean today.

A. KRISTA SYKES

Could you discuss the process of crafting AquaPraça? How did it come to exist?

ERIC HÖWELER

About seven months ago, Carlo reached out about collaborating on a floating pavilion as a venue for the biennale, and Meejin and I agreed to collaborate with him. We’ve known Carlo for years, and we share interests in technology, information, and an expanded definition of architecture to include media and interactivity.

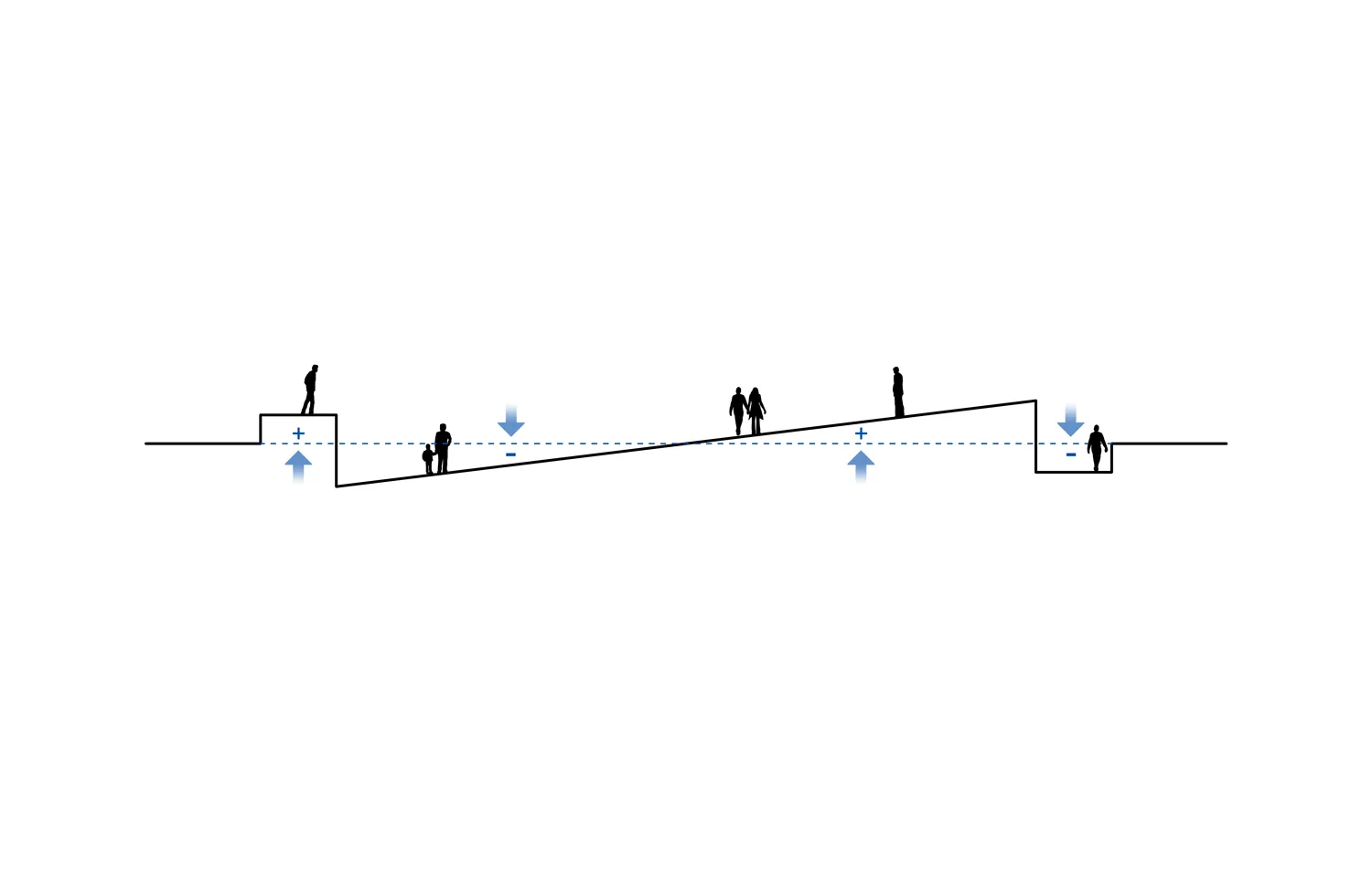

AquaPraça creates a new public space in the lagoon, allowing visitors to view the surface of the water at eye level. It relies on principles of buoyancy and displacement of water with air. The balancing of up and down, water and air creates the section of the project, which is a diagram of equilibrium.

Carlo approached the Italian government to sponsor AquaPraça and they came up with the idea that it could become the Italian pavilion for COP30, to be held in Belém, Brazil. After the conference it will become a gift from the Italian government to the Brazilian people. The biennale only lasts a few months, but what is its legacy? Now AquaPraça becomes this gift, a place for world leaders to discuss policy and climate, gathered around a water table. Then it becomes a permanent part of Belém’s cultural infrastructure, a gift to the public realm and a lasting reminder of the biennale and COP30 in the Amazon.

With the support of the Italian government, they began fabrication with the firm Maestro Technologies, a spin-off of Carlo Ratti Associati. Maestro commissioned Italian steel fabricator Cimolai to build AquaPraça. Cimolai fabricated it in less than six months, which is astounding. AquaPraça happened so fast. They finished fabrication last week and transported AquaPraça to Venice by tugboat. And now, moored off the Arsenale . . . it looks like a Superstudio image, like we are in a utopian 1960s photo montage.

KRISTA

Agreed; it looks surreal, almost otherworldly.

ERIC

Yet at the same time, it is a very tangible piece of architecture. The hull is 5/8th-inch plate, and the interior is clad with metal sheet; if you look carefully, some of the welds are visible, the imperfections in the steel. You see where the plate is and where the sheet is, what’s been treated with the no-slip texture.

I always like to tell stories of concept to construction. How do we translate an idea into a material thing? Especially for students, it’s critical to think about how a work progresses through completion. We have to think through all these assembly issues—joints, plates, sequencing. The architect’s job doesn’t end with the rendering. It ends when the finished building shows up.

KRISTA

This emphasis on process and construction seems doubly important in the circumstances of AquaPraça. The result is so polished, evoking a sense of simplicity. Yet a complex reality underlies this minimalism, not only in terms of its fabrication but also its foundational principles, which tie into the Intelligens theme that governed the biennale.

ERIC

In the context of the biennale and the question of intelligence, AquaPraça fits in with ideas of natural intelligence, buoyancy, and these ancient principles associated with submersibles. It’s both high tech and low tech, which is how we talk about some other projects of ours, such as the Collier Memorial (2015) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, with its calibrated arches and robotic stone. Yet AquaPraça is also about convening, gathering, bringing people together.

KRISTA

I had the chance to see the model of AquaPraça at the Venice Biennale in June, and my mind leapt to the Teatro del Mondo, the floating theater by Aldo Rossi that was displayed during the first Architecture Biennale in 1980. What role, if any, did the Teatro del Mondo play in the conception of AquaPraça?

ERIC

Carlo often refers to the 1980 biennale and the Teatro del Mondo, positioned as an archetypal form and a recovery of history.

I think the best architecture allows different people to read it differently. If you see the Teatro del Mondo in AquaPraça, that’s great. Last week when I was there, kids were playing in AquaPraça’s trough of water, running around the surface, loving the fact that it’s tilting. Someone else will look at AquaPraça and see Claude Parent and Paul Virilio’s Oblique Function, a perpetual destabilizing condition that creates a constant revolution of ideas. Architecture needs to be accessible at different levels and provide different readings.

Architecture also allows us to see the world around it differently. Our Memorial to Enslaved Laborers (2020) at the University of Virginia—I say it’s a horizon, because its form rises and falls, masking the city. Similarly, when you’re in AquaPraça, you don’t see Venice anymore. You’re focused on water as an object now. AquaPraça becomes a kind of perceptual device—an instrument for looking at the city, for looking at water, from a different perspective. Venetians look at water all the time, but they’re on a bridge gazing down on it, or they’re on a boat traveling across it. Rarely are they asked to contemplate it.

We talk about eco-literacy; can we train people to read their environment and their role within it? One of the problems with human behavior is we don’t realize how much energy we’re consuming. We don’t realize how wasteful it is when we throw something in the trash. It just goes somewhere else. And I believe that tracing things, making things and processes visible, builds a kind of literacy.

Something like AquaPraça supports eco-literacy. Looking over its edge last week, I was shocked to notice fish in the lagoon—little fish, lots of them. And then I saw big fish. I’ve never noticed fish in Venice, but this vantage point slowed me down and it made me pay attention. I saw the lagoon as a habitat, not a means of transit. There are lots of Venetian fishermen, and they know it’s a habitat. But for many of us, we don’t think about fish living there, or if the water is clean or healthy.

KRISTA

I propose that envisioning a life for AquaPraça beyond its initial use supports eco-literacy as well. After the Venice Biennale closes, AquaPraça will travel (via ship) to Belém for COP30, serve as a venue there, and then become a permanent piece of the city’s cultural infrastructure. That’s a remarkable story.

ERIC

Nowadays, the idea of building for an event and then letting work fall apart—as we’ve seen with Olympic parks in the past—is out of date. Everything now must imagine its afterlife. So Belém is the afterlife for AquaPraça.

This does present challenges, though. For example, who’s going to maintain it? During the COP conference, AquaPraça will float in front of a museum called Casa das Onze Janelas, or the House of Eleven Windows. It’s an historic colonial-era palace, quite beautiful. They’re going to put in piles and moor AquaPraça there with a gangway.

So, in some ways, AquaPraça’s still a work in progress, as are many issues it raises. For example, how do we gather around climate questions? How do we come together to address and speculate on solutions? I think that the Belém chapter will add to this dimension. It’s not just a demonstration; it’s actually helping to make an impact.

These days I say that an architect can design one building, 10 buildings, 50 buildings, and each building is going to be as thoughtful, smart, and energy efficient as it can be. But it’s hard to think about adding up all these buildings to some sort of climate impact. Beyond the individual building, how do we communicate alternative means of working, an alternative lifestyle, whether it’s high density near transit or something else? So rather than simply trying to save energy with one building at a time, I wonder: perhaps every building could broadcast, signal, amplify a way of thinking about lifestyle that’s not just about measurements of energy savings. I think conveying alternative versions of cities, alternative versions of landscapes that broadcast function is probably more impactful than me privately saving energy myself. In other words, can we enlist others to operate, to live, to commute differently? More and more I think a responsible architecture is about showing alternatives and trying to enlist others to behave differently.