Before BILLY: A Brief History of the Bookcase

I grew up in a domestic world that seemed to hospitably reconfigure itself around our family’s evolving interests and enterprises. As my younger brother’s model horse and airplane collections expanded, new built-to-scale stables and hangars appeared on the walls above his bed and beside his desk. As my mom’s canning repertoire grew to include peaches, new wooden racks arrived in the laundry room storage closet and in the basement. Even when I moved away from home with my ever-expanding stock of books—first to a teensy, closetless studio in New York City, then to a comparatively cavernous, amenity-free loft in Philadelphia—new shelves appeared to contain the collection.

Those Philadelphia-born shelves, mahogany and cherry quadruplets seven feet high and five feet wide, rolled in on wheels so I could move them around, partitioning all that cold, alienating space into human-scaled, homey alcoves. That wood and I shared roots: it came from the ridge behind my family home, from the hardware store my dad owned with his two brothers, and from various central Pennsylvania barn sales. The milled lumber then became furniture, made to order by my dad in his woodshop. There was no Ikea anywhere close to the rural town where I grew up. We didn’t even know the Swedish flat-packers existed. And even if one of their big blue stores had been within driving distance, I’m quite sure it would’ve been verboten since, as we were taught over the years, you really can’t trust a butt joint.

Still, Ikea’s shelves and cabinets, especially its iconic BILLY bookcase, are among the world’s most ubiquitous furnishings. Such casework contains much of the stuff of our material existence—all the stuff, that is, that doesn’t fit in the closet or chest of drawers. The mis-fit could be either physical (i.e., an object is too big or bulky, hard to hang, or prone to getting lost in a bottomless bin) or conceptual (some things, like model horses and books and candy-colored jars of jam, simply belong on shelves). We put things on shelves, rather than behind doors or in drawers, when we want them to be readily graspable, when they’re sufficiently attractive for display, when they lend themselves to an ordered presentation, when they’re not susceptible to dust or light or children’s sticky fingers or other environmental hazards.

We’ve been putting things on shelves for thousands of years. Our nomadic Paleolithic ancestors likely encountered naturally occurring ledges in their rock shelters, which provided convenient resting space for stone and bone tools.

Their Neolithic descendants, who settled and cultivated the land and built more permanent dwellings, produced agricultural surpluses that needed to be stored. Baskets and pottery held grain in communal granaries, or they sometimes sat on shelves or nooks in the wattle and daub or stone walls of individual dwellings. In mud-brick homes of ancient Mesopotamia, wooden shelves likely held cooking implements and other household items, while the municipal archival rooms at Elba and Nippur housed clay tablets, the community’s records of account, on shelves or in wooden pigeonholes.

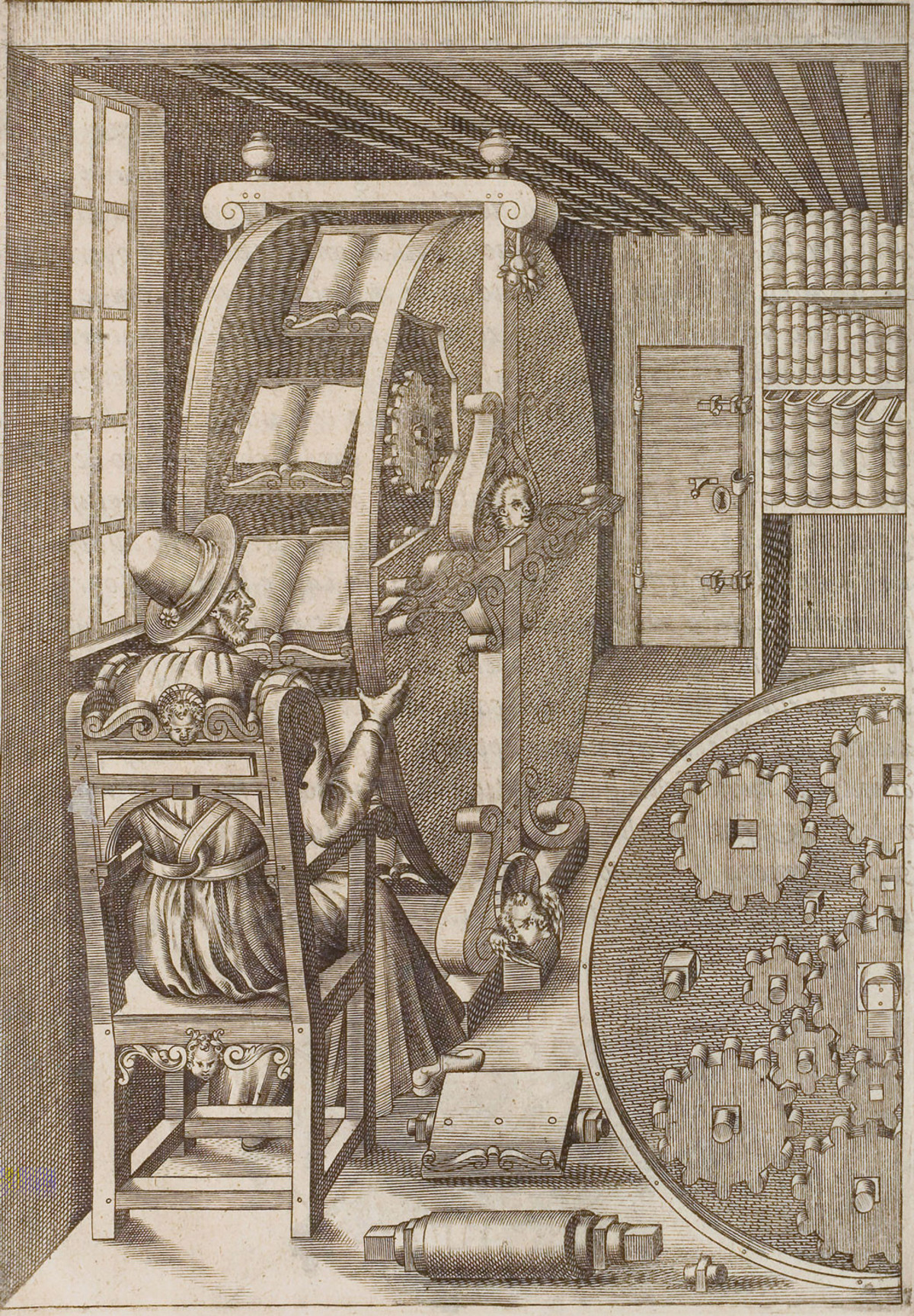

Shelves have evolved along with the walls that have supported them; thus, to some degree, the history of shelving is bound to the history of architecture. Yet the history of the shelf is not a history of great architects. While we have met some iconic shelves through the years—from Agostino Ramelli’s 16th-century rotating book wheel to Dieter Rams’s 606 Universal Shelving System from 1960—most of our racks and stacks comprise an anonymous history, one pieced together by examining archaeological literature on ancient vernacular buildings and contemporary industrial design catalogs. Yet one particular species of shelf has received special historiographic attention: there exists enough scholarship on the history of the bookshelf to fill, well, an entire bookshelf.1

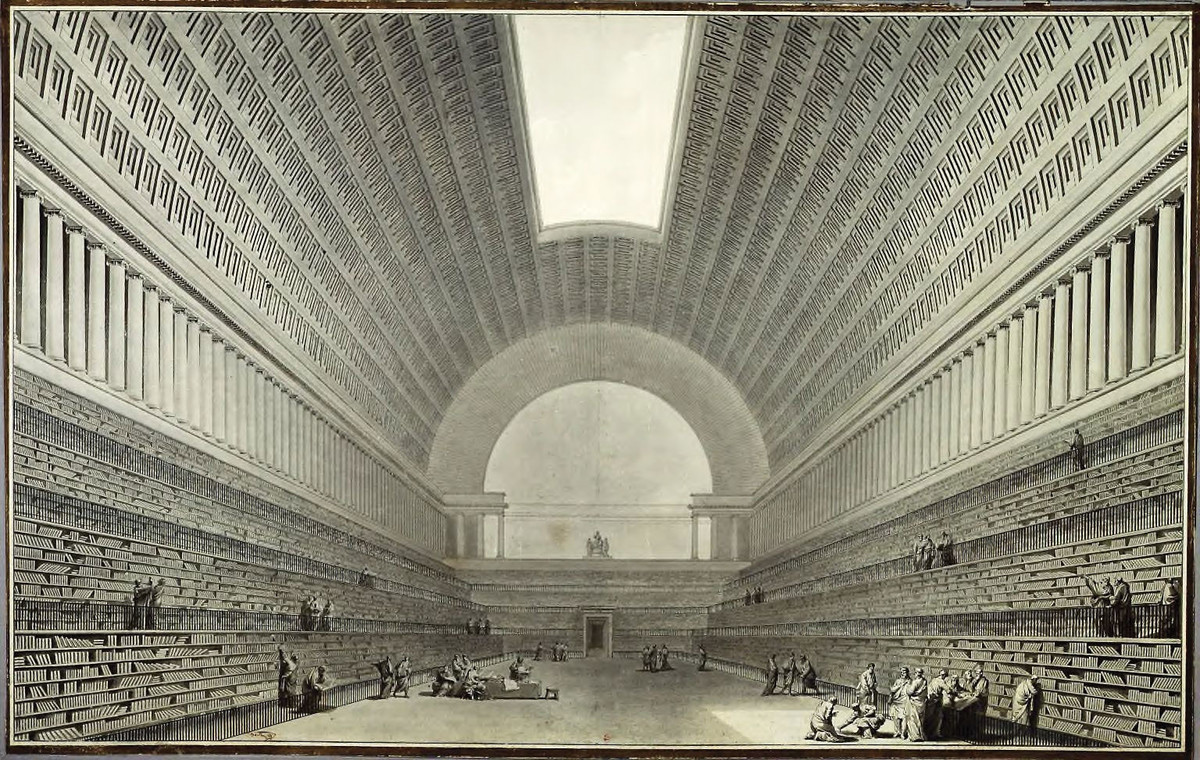

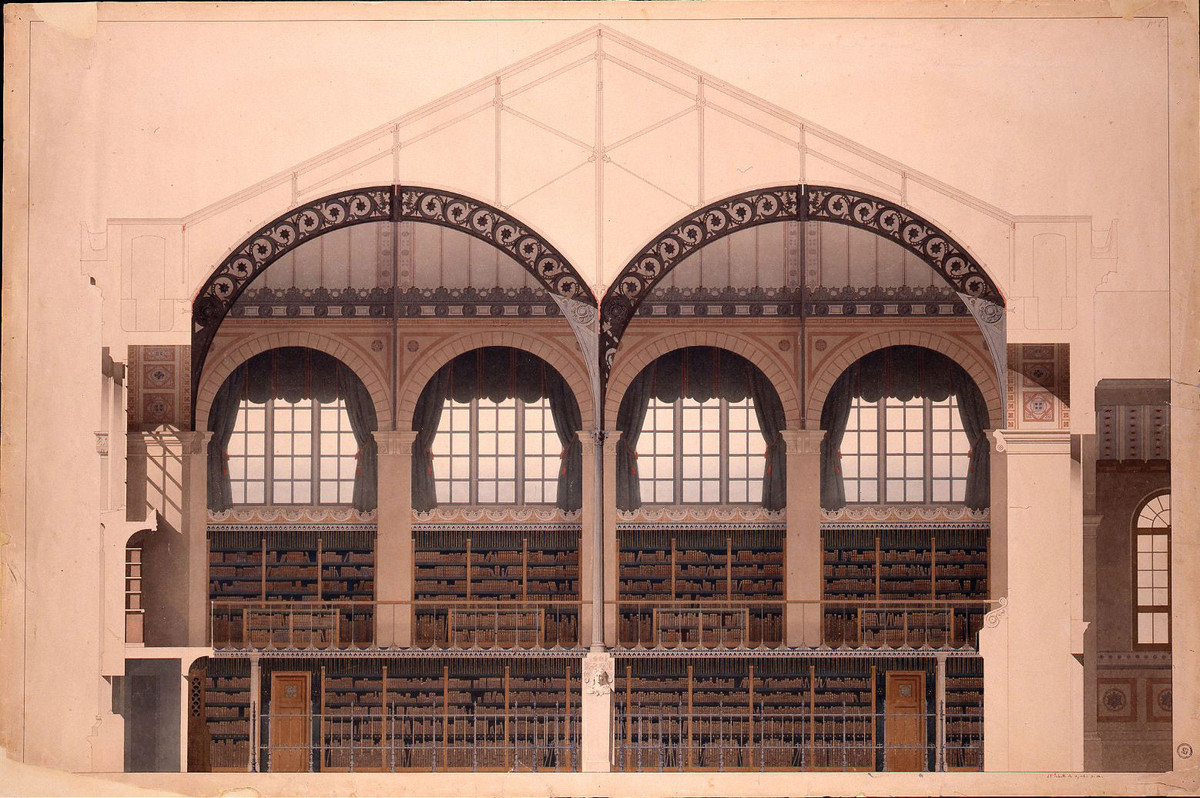

The interior walls of many European libraries of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries were lined with wooden bookshelves, some heavily ornamented, some offering attached desks or lecterns. Étienne-Louis Boullée famously envisioned open, browsable multitiered shelves for the Bibliothèque du Roi (soon to be renamed Bibliothèque nationale de France) in Paris in 1785. By the 19th century, the increasing use of cast iron and glass as building materials opened new design opportunities, including the multitiered metal bookstack, and brought light and volume to book storage and reading areas. In 1850, Henri Labrouste’s Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, also in Paris, placed the reading room atop a multilevel stack, yet kept the reference collection in two-tiered shelves in the reading room. His later design for the Bibliothèque nationale positioned the skylit, five-level, glass-floored bookstack adjacent to the reading room and visible through a glass wall, but again kept the reference collection in three levels of wall stacks in the reading room.

According to Marc Le Cœur, one of the curators of the Museum of Modern Art’s 2013 Labrouste exhibition, “The public could not enter [the stacks] but [could] sense their importance by the gigantic size of the glass opening (nine meters high) within the converging walls of the hemicycle and by the sculpted medallions of great authors above the bookshelves all shown in profile facing the stacks.”5 These visible-but-inaccessible stacks rendered the collection, and the knowledge it embodied, monumental and guarded. The glass wall embodied an intellectual barrier between published knowledge and the making of new knowledge. Many 19th- and early 20th-century realizations of the iron stack resulted in the collection being removed, in large part, from the reading room.6

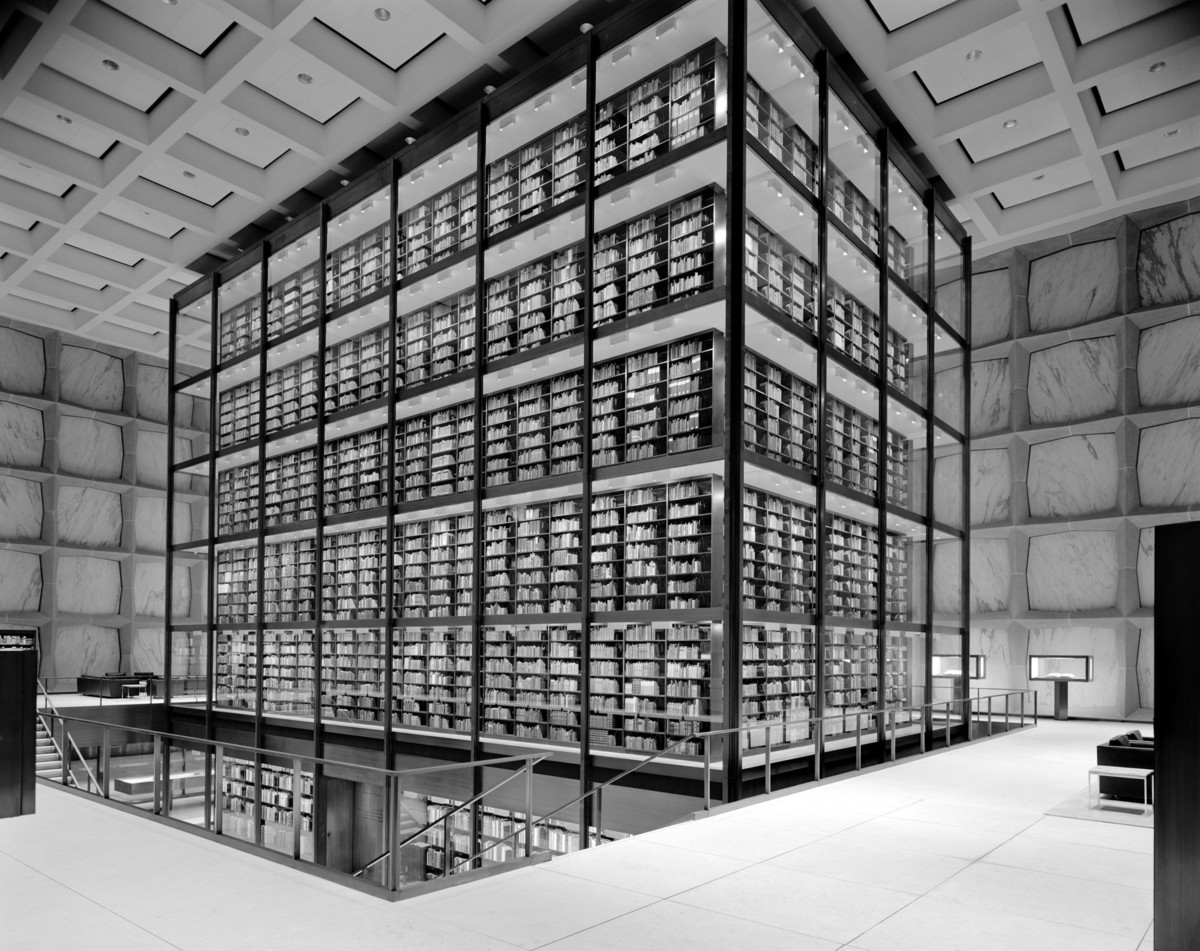

The metal bookstack reigned supreme in institutions for much of the late 19th and 20th centuries. Still, in that period the book storage industry did evolve with the advent of rolling and sliding shelves and compact shelving (some of which is now automated, like the University of Chicago’s Helmut Jahn–designed Joe and Rika Mansueto Library [2011] and North Carolina State University’s Snøhetta–designed James B. Hunt Jr. Library [2013]). Even as collections move off-site and out of sight, there’s a growing public fascination with the aesthetics of storage. For some, that interest is reactionary: the proposal of a new off-site storage endeavor means the obsolescence of the stacks, and with it, apparently, the aesthetic and ethos that defined the traditional library. These were among the central concerns surrounding the proposed renovation of the New York Public Library’s 42nd Street building, and led to the old stacks becoming a cause célèbre between 2012 and 2014.7 But for others, that interest is perhaps partly fetishistic (robot librarians!), and partly a genuine desire to understand a system with a nonintuitive logic—that is, to understand what “code space” looks like.8 These collections aren’t organized for browsing or human intelligibility; instead, the shared logic of the shelving and inventory systems prioritizes efficient storage and retrieval.

Yet the aesthetics of the old-fashioned, public-facing stack still seem to be in fashion. Perhaps this nostalgia is in response to or functions as a rejection of the black-boxed minimalism—or, conversely, the twisted rhizomes—of digital aesthetics. TAX arquitectura’s Biblioteca Jose Vasconcelos (2006) in Mexico City, for instance, and MVRDV’s Book Mountain (2012) in Spijkenisse, the Netherlands, continue to fetishize the stacks. We see similar focus on the aesthetics of storage in some special collections, including Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates’ Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College (2000); and of course its formal predecessor, the seminal design by Gordon Bunshaft, of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (1963). The epistemological implications of this aesthetic might seem obvious: these architectural projects put on display, and make empirical, if not always navigable, the wealth of knowledge that their collections represent. Yet, in the digital age, these analog monuments take on new meaning; they might represent a wistful return to the tangible, or they might be an attempt to render empirical, affective, or phenomenological the taxonomies and algorithms that so palpably, if invisibly, structure our collections—and our everyday lives.

Since the days of Mesopotamia, the homes of nobility had been stocked with tablets, scrolls, and codices, and these elites’ private libraries formed the foundations of many historically significant institutional collections in the ancient world. Yet it wasn’t until after the spread of mechanical reproduction, when printed matter was made more accessible and affordable, that the private library became a more egalitarian possibility. Particularly in the 19th and 20th centuries, new literary forms, new capacities for mass printing, and new reading habits, along with the expansion of public education, transformed the place of books in Westerners’ everyday lives.9 Meanwhile, the emergence of new consumer goods and practices of consumption and collection gave rise to what Walter Benjamin described as the overstuffed “bourgeois interior.”10 People needed cases, receptacles, and shelves not only to store, but also to display their ever-expanding assemblages of books and baubles and gadgets—which together cultivated the “appearance of respectability and plenitude.”11 The history of the bookshelf thus expands here into something bigger, as the books are intershelved with other accessories and artifacts.

While the Victorians had their glassed-in display cases and barrister bookcases, interwar homeowners more frequently opted for built-in shelving. The books on the family bookshelf and personal papers in the secretary desk were joined by new media: mass-circulation periodicals, record players, telephones, radios, and, eventually, TV sets. As media theorist Lynn Spigel explains, manufacturers—in an attempt to facilitate the integration of these new, potentially intimidating and unsightly objects into the home—often camouflaged their contraptions in cabinets styled to match popular domestic decor, which meant a lot of hideous Chippendale-style TV sets.12 Manufacturers and consumers adopted similar approaches when the hi-fi system appeared in the 1950s and 1960s, creating attractive consoles and built-in storage to mask the machines and their wires.13

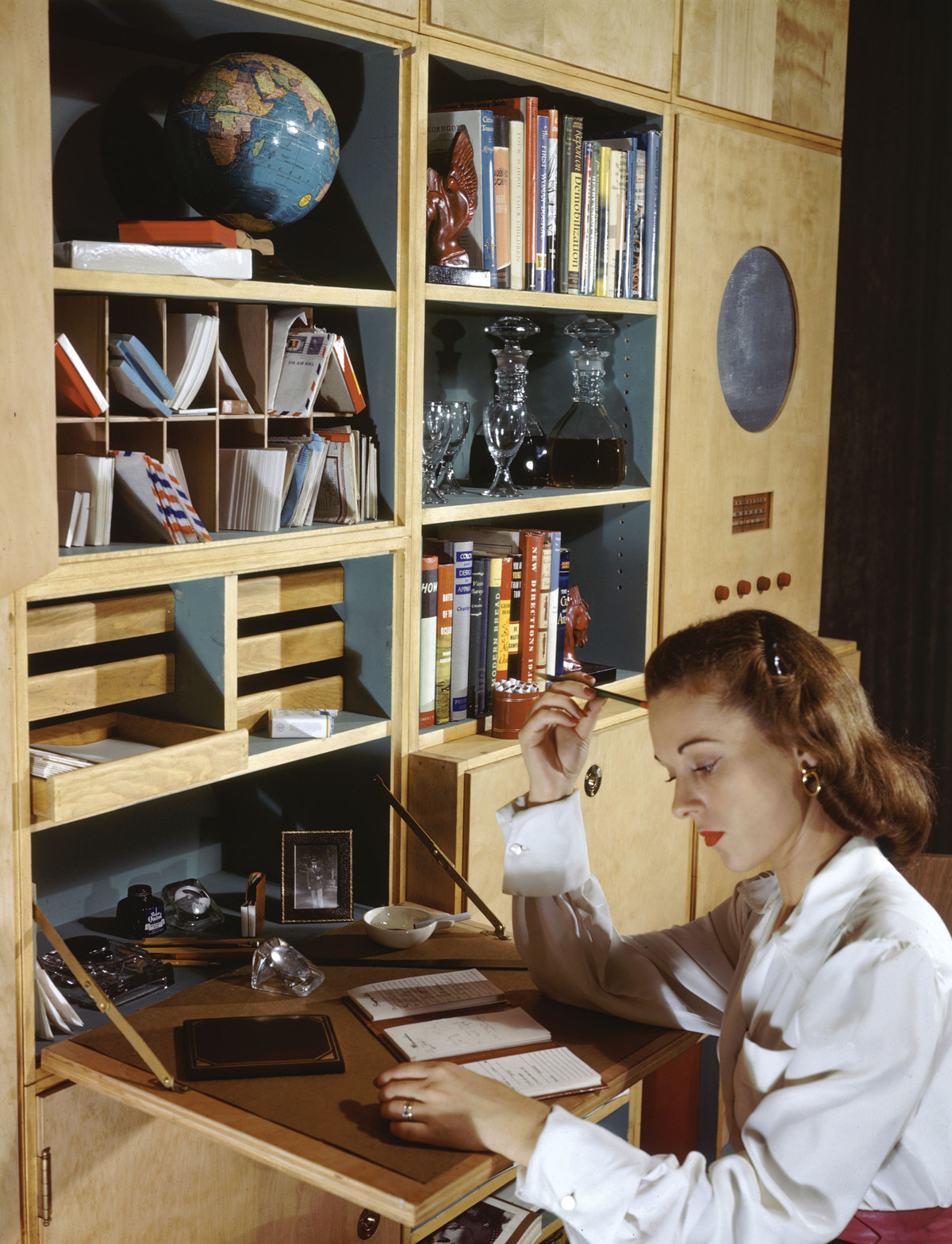

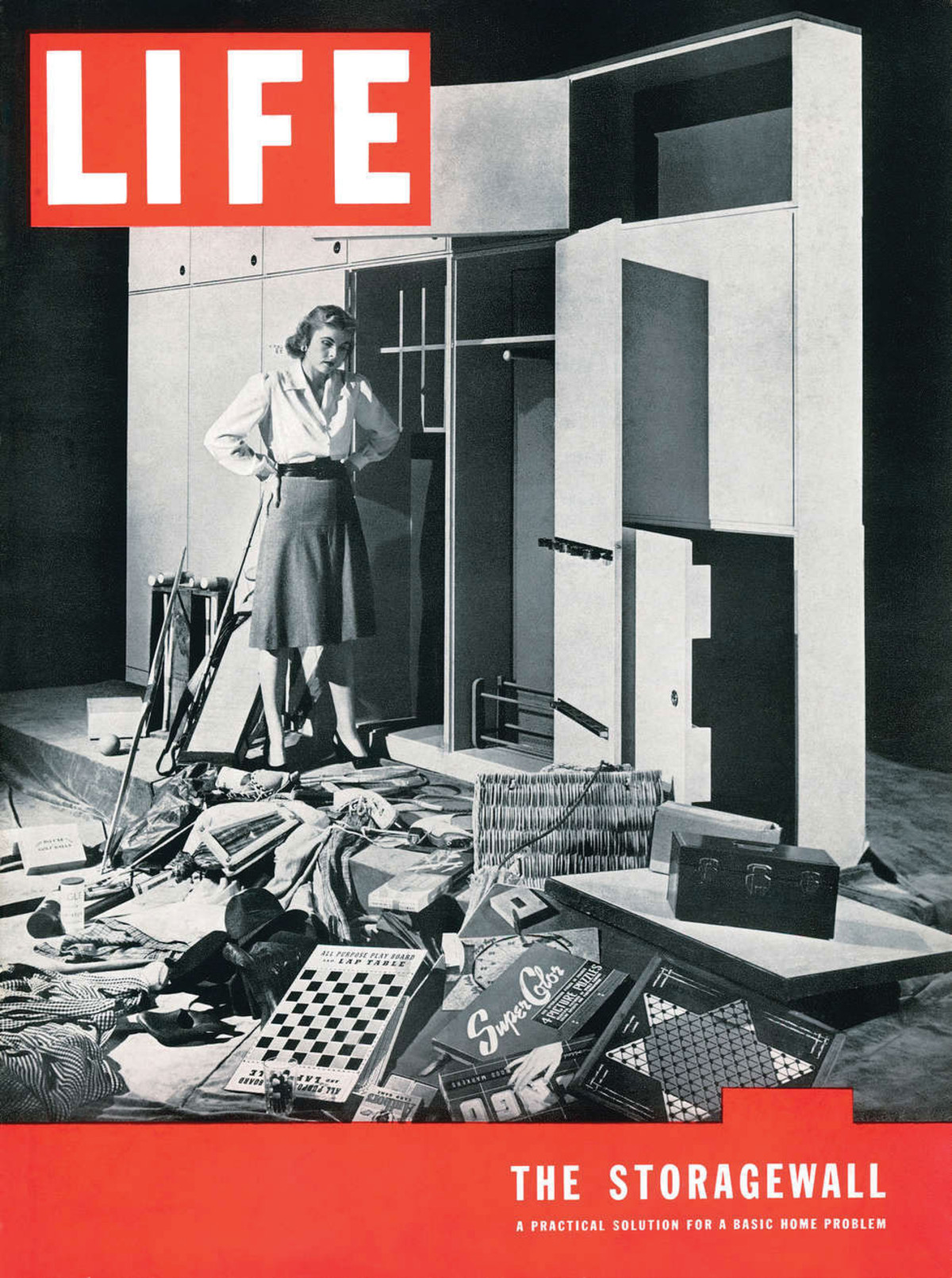

Frustrated with these mass-produced solutions, and appalled by the increasing clutter of the postwar home and its open plan, some noted designers decided to tackle the aesthetics of storage. George Nelson and Henry Wright’s 1945 book, Tomorrow’s House, included dedicated sections to such topics as lighting and heating, living and dining rooms, sleeping and sound conditions—and storage. Here, Nelson introduced his Storagewall, which included bookshelves and magazine racks, a built-in radio, a drawer for a record player, speakers, a foldout desk with cubbies for document storage, a wet (liquor) closet, a game closet, and a space for storing vases.14 The unit—a postwar version of Le Corbusier’s Casiers Standard modular storage cabinets—integrated dedicated spaces for old and new media, for leisure-time equipment, and for ornamental objects through which one, typically the woman of the house, could communicate personal taste.

A few years later, in 1960, Rams introduced his still-popular 606 Universal Shelving System. Much less “architectural” than Nelson’s hefty, cabinet-enclosed Storagewall, Rams’s system can be either wall-mounted or freestanding. When its thin aluminum posts are loaded with modular fittings—shelves, drawers, desks—and stocked with books, sleek machines, dishes, and ornaments, the 606’s cargo appears to float free from the wall and off the ground. Not so with Gillis Lundgren’s BILLY, introduced by Ikea in 1979. Its veneered particleboard shelves stretch all the way to the floor and tend to groan and bow under the weight of a grad student’s library. The illusion of weightlessness, of floating stuff, doesn’t come cheap: a single bay of Rams’s shelves is about 12 times the cost of Lundgren’s 79.5-inch case. With an investment of that magnitude, the 606 seems to compel not only the careful “curation” of its contents, but also the aestheticization of storage itself: it makes a subdued spectacle of its sublime engineering. Meanwhile, BILLY’s relative affordability and accessibility have made it a prime candidate for unauthorized modification. Hacking and customizing the flat-packed kits, its consumers become engineers, reconfiguring their storage environments to reflect and accommodate their interests, enterprises, and tastes.

Today, those interests and tastes are appealed to and satisfied in environments that adhere to a different engineering logic. Amazon’s fulfillment centers, with their shelves carted around by little Kiva robots, operate in accordance with the laws of logistics, which means that books, originally Amazon’s bread and butter, might be shelved next to, well, bread—or, more likely, other assorted nonperishable items that simply happen to fit the available shelf real estate. While some of those books might seem to be disappearing from the warehouses’ metal racks altogether, as they float between Amazon’s Cloud and the virtual library shelves on our Kindles, that Cloud actually resides on metal shelves, too: on server racks in its data centers. Even virtual goods require material, if off-site, storage.

Yet piles of print still occupy Amazon’s warehouse racks (and, now, stacks in its brick-and-mortar bookstores). Picture books and cheese graters, toy airplanes and athleisure wear are merely stored and retrieved here, with the expanse of utilitarian shelves serving as a holding ground between receiving and shipping. When those boxes reach our doorsteps, we extract their contents from voluminous packaging material and plastic wrap and place them on their appropriate shelves: the book in its wooden case, the grater in its cupboard, the horse in its bespoke stable, the yoga pants in their drawer. What were, only a few days before, systematically coded wares in a miscellany of merchandise, are now individuated objects, appreciated for their distinctive functions or aesthetic values, classified and authorized, in part, through their place on the shelf.

Before books, there were scrolls. The ancient Romans, like the Sumerians, stored their extensive scroll collections in “cells,” or pigeonholes (nidus, forulus, or loculamentum), or on pegmata, platforms composed of planks of wood that were typically sold along with the house. Pegmata were thus among the first built-ins, or shelves-as-fixtures. After Atticus loaned a few of his literate Greek slaves to Cicero to build new pegmata and arrange the books in his villa, Cicero proclaimed that “your men have made my library gay with their carpentry-work and their titles. . . . [A] new spirit has been infused into my house.”2 As the scroll evolved into the bound codex in the final centuries of the Roman Empire, libraries more frequently stored written matter in wooden cabinets (armaria) arranged along the walls of a room. And throughout the Middle Ages, as scribes laboriously copied books by hand in scriptoria, they continued to secure their precious and expensive tomes in armaria, whose cabinet doors mediated access.

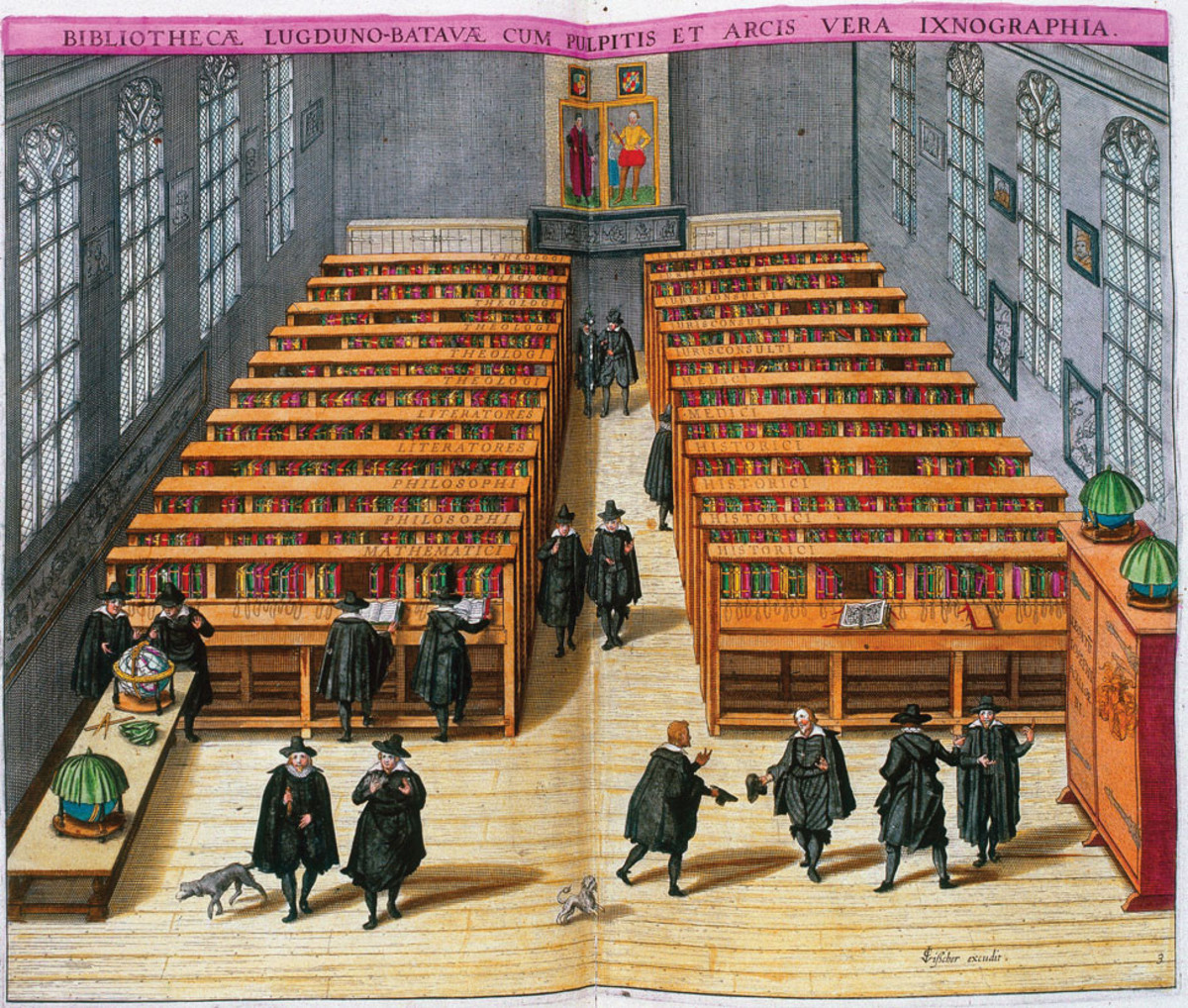

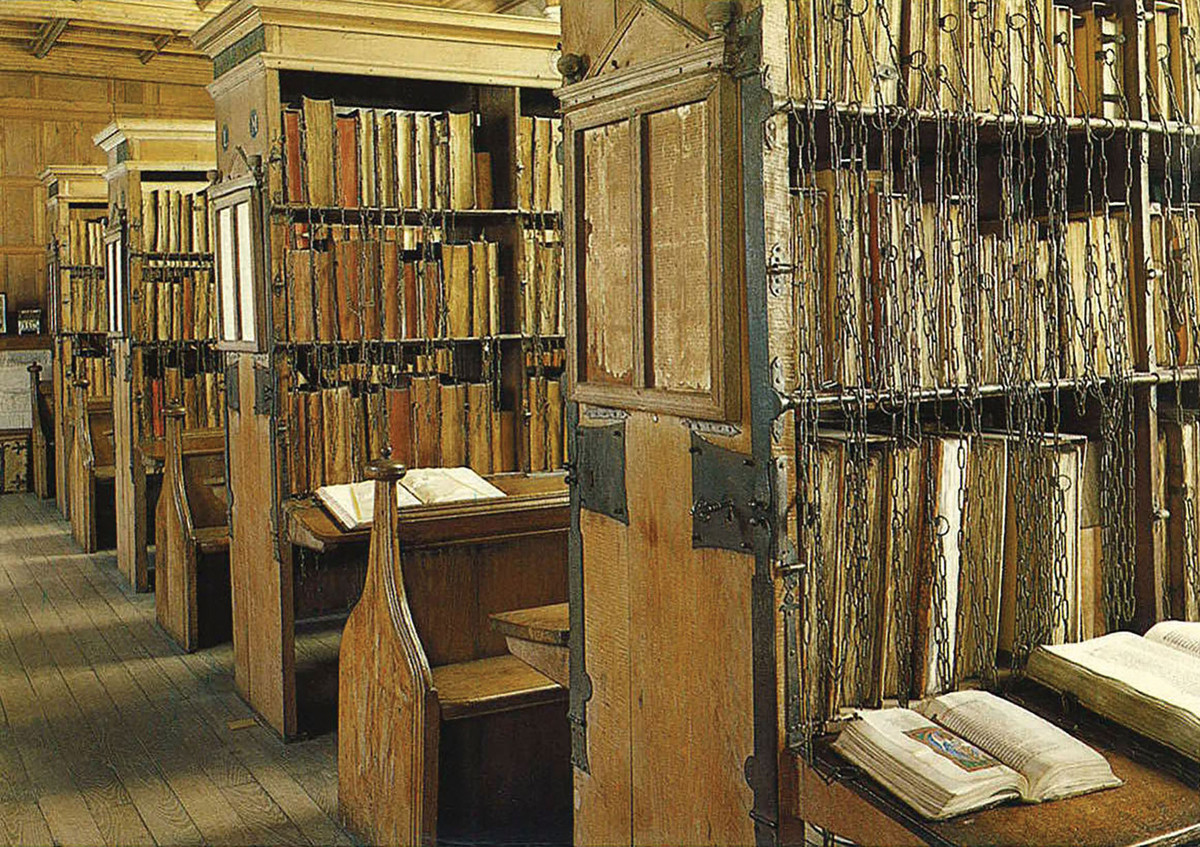

With the rise of monastic and university libraries, however, books were displayed more openly—for access by patrons and as a statement of an institution’s cultural capital. Yet the materials still needed to be kept secure. Few storage strategies are as blatantly symbolic, and so stereotypically “medieval,” as that of the chained library.3 Books, with chains affixed to their covers, were tethered to iron rods and laid upon lecterns, which often had shelves above and/or below the reading surface where patrons could store additional texts, thus freeing up workspace. Historian Robert Darnton writes of a library scene at the University of Leiden, portrayed on a print dated 1610: “It shows the books, heavy folio volumes, chained on high shelves jutting out from the walls in sequence determined by the rubrics of classical bibliography: Jurisconsulti, Medici, Historici, and so on. Students are scattered about the room, reading the books on counters built at shoulder level below the shelves. They read standing up, protected against the cold by thick cloaks and hats, one foot perched on a rail to ease the pressure on their bodies. Reading cannot have been comfortable in the age of classical humanism.”4 The shackling began in the 15th century and continued in some libraries through the late 18th century. The Hereford Cathedral Library in the United Kingdom is among the few institutions that have retained their chains to this day.

With everything lying flat, and with stacking made difficult because of the unwieldy chains and the occasional ornamental book cover, shelves had limited capacity. The inefficiencies of horizontal book storage eventually led to the consideration of a different orientation. Those chained books were turned upright, often with their fore-edges facing out, on shelves above the library lecterns. Eventually, as books became more plentiful, the chains came off and the lectern metamorphosed into the book “press,” a bookcase that could be closed. With the book newly emancipated, so too was the reader freed to take books away from the stacks to a nearby stool, bench, lectern, or table. The mobility of the book afforded the user a sense of control over its use, a more comfortable engagement with it (thanks, also, to the arrival of smaller print formats), and, perhaps, greater intellectual liberty.

12. See Lynn Spigel, Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992). 13 See Dianne Harris, “A Tiny Orchestra in the Living Room, High-Fidelity Stereo and the Postwar House,” Places Journal, April 2015, https://placesjournal.org/article/a-tiny-orchestra-in-the-living-room. 14 See Lynn Spigel, “Object Lessons for the Media Home: From Storagewall to Invisible Design,” Public Culture 24, no. 3 (2012): 537.

Shannon Mattern is associate professor of media studies at the New School. She teaches and writes about archives, libraries, and other media spaces; media infrastructures; and spatial epistemologies. She is the author of The New Downtown Library: Designing with Communities (2007), Deep Mapping the Media City (2015), and the forthcoming Ether/Ore: Archaeologies of Cities and Media.