Excavating Environmental Histories at Pompeii’s Casa della Regina Carolina

Ancient pollen trapped in fresco wall-paintings, like a mosquito in amber, provides a historical ecological snapshot. Compacted grains of garden soil preserve 2,000-year-old footsteps. Even the tiniest artifacts allow us to unpack, reconstruct, and map environmental conditions and lived experiences in the ancient Roman Mediterranean world—knowledge that can inform our actions in the present day.

An assistant professor of environmental history in the Department of Landscape Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), I co-direct the Casa della Regina Carolina (CRC) Project at Pompeii—a collaborative archaeological excavation co-sponsored by the GSD, Bologna University, and Cornell University, with the support of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii. Since 2018, the CRC team has been excavating one of the largest urban gardens in the ancient city.[1] This interdisciplinary endeavor—combining archaeological studies of architecture, botany, ichthyology, and more—investigates ancient resilient design practices, the lives of non-elites, and the impact of Roman colonization on the urban fabric.

The Casa della Regina Carolina, a property named after Queen Caroline Murat, née Bonaparte (an influential patron of early excavations at Pompeii), is a wealthy dwelling, located near the civic center of Pompeii. The house and its 730-square-meter garden was originally excavated and cleared of volcanic ash in the early 19th century before the development of modern scientific archaeology. Yet, by the end of the century the house had been largely forgotten and ceased to appear prominently in either tourist itineraries or published scholarship.

Today, the CRC is the subject of renewed attention. Over five seasons of study, the CRC Pompeii Project has explored the ways that the study of the past and future inform one another. As an archaeological project, CRC Pompeii investigates human and non-human interactions at the time of Pompeii’s destruction: 79 CE, during the Roman Climate Optimum (200 BCE–150 CE), an era characterized by unusually stable and warm environmental conditions. At the same time, because modern Pompeii is endangered by extreme weather events such as flash flooding, the project also attends to issues related to cultural heritage and biodiversity preservation. This work requires a prismatic approach that interweaves design thinking, archaeological investigation, and mentorship of future generations of scholars and designers.

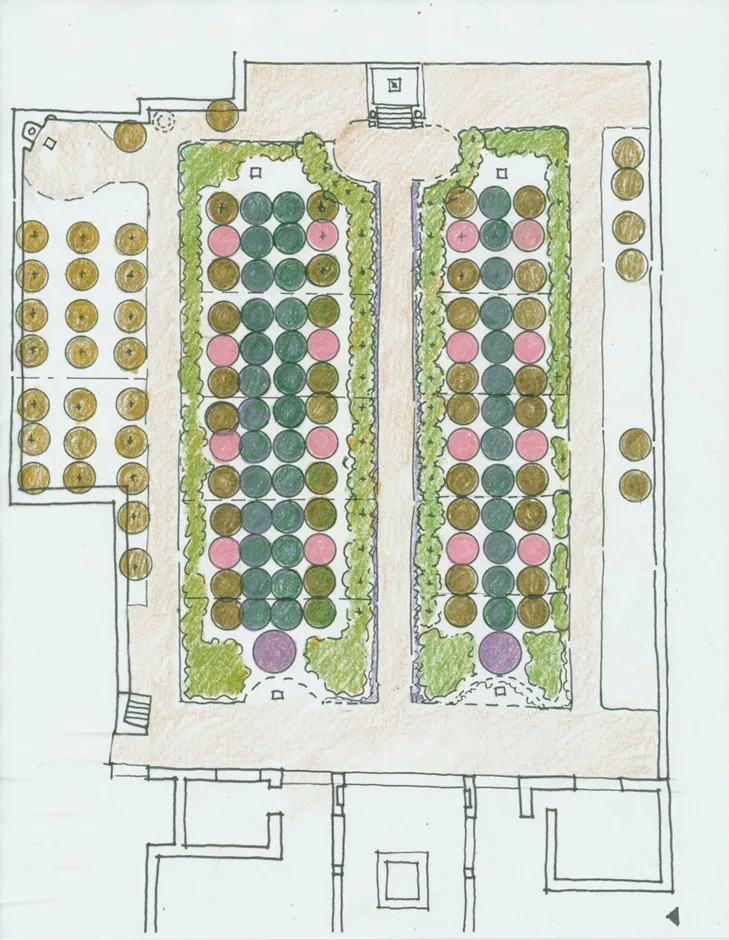

The 2025 field season, composed of nearly 50 students, scholars, and volunteers, was focused on completing the excavation of the CRC’s large garden. Like many others at Pompeii, this garden was created after the devastating earthquake of 62 CE, which damaged much of the city. As part of a resilient response, workers used rubble to create a level foundation on top of the remains of earlier domestic structures. They deposited soil over the rubble and gardeners subsequently installed plantings. Since the CRC team began excavating the garden in 2018, we have discovered ancient garden walks, locations of planting pits, post holes from fencing or trellising, and planting pots, allowing us to reconstruct the overall design. Our 2025 findings have underscored that, at the time of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, this property was undergoing heavy renovations—a trend mirrored across the city.

My own work focuses on the study of ancient landscape designers and gardeners, so I am especially interested in what this large urban garden can tell us about the individuals—likely predominantly enslaved—who designed, installed, and maintained this space. Because no text written by a landscape designer or gardener survives from antiquity, ancient soils and plant remains offer an invaluable archive for discovering horticultural labor history. To reveal these hidden narratives, I collaborate with a host of specialists to document and delve into the site.

As part of a new CRC initiative, this summer GSD landscape architecture student Marko Manriquez (MLA I ’27) joined the team in Pompeii. Manriquez’s expertise in aerial photography, photogrammetry, and LiDAR scanning added a crucial and cutting-edge component to our investigations of the site. “LiDAR fires thousands of laser pulses each second—each pulse a question hurled at stone, each return echo an answer about distance, texture, the precise curve of a fallen column,” Manriquez explains, contemplating the role of light in documenting historic landscapes.

“These measurements stitch themselves into 3D skeletons of ruins, bone-accurate reconstructions of what was,” Manriquez continues. “Gaussian splats push further still: millions of colored pixels clustering like digital pollen, each fragment positioned in space until they birth immersive worlds you can walk through, turn around in, inhabit. The ancient dust becomes data voxels—fragments as real as the coins in my palm, as haunted as the walls I traced.”

The ancient plant artifacts of which Manriquez speaks is a subject of study for Dr. Jessica Feito, an expert in archaeobotany (the study of preserved plant remains). [Fig 11] A Marie Skłodowska-Curie postdoctoral researcher at the Catalan Institute of Classical Archaeology in Tarragona, Spain, Feito’s research explores many aspects of past lifeways, including diet, agricultural economies, fuel use, and human–environment interactions. “Plant remains are excellent proxies for past environments and are a key resource in studying periods of climatic change and instability throughout history,” Feito states. “Environmental conditions impact what plants grow in the wild as well as the plants that can be cultivated and the techniques necessary for their cultivation.”

On site at the CRC excavations, Feito often employs “flotation,” a process using water to separate archaeobotanical remains, such as seeds, from the soil. With a microscope she then examines and identifies the seeds—and ultimately the plants—that were present at the site in ancient times. In this way, her work contributes to understanding not only the plants that were grown in the garden and used within the household, but also aspects of the cultivation practices and activities that took place within the space.

Dr. Lee Graña, a research fellow at the University of Bologna who specializes in environmental archaeology and Roman coastal economies, further contributes to uncovering activities carried out at the CRC and ancient Pompeian marine settings. Graña’s research focuses on ichthyofaunal (fish bone) remains recovered from coastal and wetland sites, vestiges that offer vital clues to Roman fishing practices, dietary habits, and trade. Furthermore, by analyzing species diversity, habitat preferences, and seasonal catch patterns, Graña reconstructs ancient marine ecologies and tracks long-term environmental and climatic shifts. Markers such as the extinction of native species and changes in average fish sizes trace the human impact on modern ecosystems.

“I come from a long line of Galician fishermen who practiced their art in the hope of a brighter future. I now study their story in the hope of a clearer past,” says Graña. As assistant field director and CRC Pompeii ichthyoarchaeologist, he is currently analyzing fish bone assemblages from the site. Because few ichthyofaunal studies have been conducted at Pompeii, the results of this analysis will provide new data on marine environmental and climatological conditions in the ancient city. In addition, Graña’s interdisciplinary approach—which blends experimental archaeology, zooarchaeology, and ethnoichthyology—highlights the continuation of Roman traditions in modern communities.

Questions of Roman domestic architecture and urban planning fall to Dr. Roberta Ferritto, an ancient architecture specialist. “At CRC, I examine how elite Roman households adapted their architectural spaces to accommodate both private family life and public social functions,” explains Ferritto, a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) Global Fellow who is affiliated with the University of Bologna and the University of Pennsylvania.

Located in one of Pompeii’s liveliest neighborhoods near the ancient forum, the CRC underwent various transformations over centuries of use. Catastrophic events and changes of ownership resulted in a complex mix of construction techniques from different historical phases. “To understand how this type of house functioned within Pompeii’s urban fabric,” Ferritto states, “we’re using integrated documentation methods—combining traditional archaeological recording with advanced 3D modeling, virtual reality, laser scanning, LIDAR, photogrammetry, and aerial photogrammetry.” Significantly, the CRC contains architectural peculiarities unique within Pompeii but found in a few villas elsewhere in the Bay of Naples. These relationships to sites outside the city suggest previously unrecognized connections that Ferritto is investigating through analysis of ownership and labor interactions.

The contributions of the above team members are just a sampling of the diverse interdisciplinary knowledge that makes this archaeological project possible. Indeed, studying and documenting Pompeii illuminates significant aspects of the past—including the everyday lives of ancient Romans as well as the impacts of environmental conditions on a population’s evolution. Likewise, the CRC Pompeii Project allows us to preserve this historical register as a resource for future investigations that will offer clues to weathering impending climatic shifts.

[1] The CRC Project is co-directed by Kaja Tally-Schumacher, assistant professor, Harvard GSD; Annalisa Marzano, professor, Bologna University; Lee Graña, postdoctoral fellow, Bologna University; Caitie Barrett (Harvard AB ’03), professor, Cornell University; and Kathryn Gleason (GSD MLA ’81), professor emerita, Cornell University.