An Interview with Gareth Doherty: Fieldwork, Borders, and the Landscape of Understanding

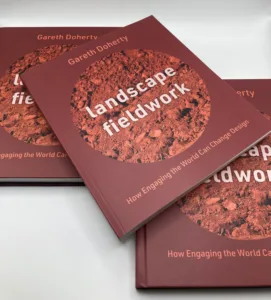

“Landscape architecture is at a crossroads,” writes Gareth Doherty in the introduction to his recent book, Landscape Fieldwork: How Engaging the World Can Change Design (2025). Even as digital tools unlock new possibilities to design landscapes from afar, the need to “to fully understand the ways that humans use spaces” has never been more pressing. The human dimension of landscape design is at the core of Doherty’s argument. Working directly with people in the field is essential for creating spaces that hold meaning for those that inhabit them.

Doherty devotes chapters to the different places he has worked, from Bahrain to the Bahamas to Brazil, detailing both the challenges of learning from different places and the transformative potential of on-the-ground collaboration.

Doherty is associate professor of landscape architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and an affiliate of the Department of African and African American studies at Harvard University. Much of his recent fieldwork has been in Africa. His collaborative work with scholars and practitioners on the continent led to the 2025 conference “African Landscape Architectures,” and this work continues to inform his pedagogy at the GSD.

In this interview, Doherty spoke with the GSD’s William Smith about his scholarship, the projects he has led through the Critical Landscapes Design Lab, and the broad potential for design to foster understanding across places and cultures.

William Smith

You argue that landscape architecture has a specific relationship to fieldwork that is nonetheless undertheorized within the discipline. How do you define “fieldwork”?

Gareth Doherty

Fieldwork lies at the heart of my work. I describe it as an immersive engagement with a site—one that not only documents and measures using multiple forms of media, but also speculates on possible futures. Landscape architects spend much of their time outdoors, yet we rarely reflect on fieldwork as a distinct form of knowledge-making. Anthropologists and geographers have long traditions of theorizing their field practices. We, by contrast, often go to sites, take measurements, and move on. My book is an attempt to make that implicit practice more reflexive—to show how fieldwork generates design intelligence.

A colleague once told me, “Fieldwork for a landscape architect is like breathing.” I understood what he meant, but I think of it more like riding a bicycle. We are not born knowing how to do it. We can learn it, even if we end up falling off a few times during the process. The book Landscape Fieldwork: How Engaging the World Can Change Design, is meant to instruct design professionals and researchers on how to conduct fieldwork, but only in as much as a book can help with practice. To become good fieldworkers, each one of us will have to find our own balance. Once mastered, it takes you somewhere new—from one reality to another.

Good fieldwork allows us to enter other worlds respectfully—to understand societies not our own, and to design with empathy rather than imposition. Landscape fieldwork is uniquely complex because it integrates spatial, temporal, and environmental dimensions. Yet we often neglect the social dimension, and that’s where my work insists on focus. Understanding people—their rituals, needs, and perceptions—is what grounds design in reality.

William

How do you conduct fieldwork? What do you actually do?

Gareth

I immerse myself in the landscapes I’m studying as much as I can, including engaging with the communities who inhabit them. When students ask what tools to bring into the field, I remind them that the most important tool is the body. Our bodies are the medium through which we perceive the world. Sure, you can bring an iPhone, a measuring tape, or a drone—but it’s through subjective immersion that new understandings arise.

Landscape architects, fortunately, are polymaths of media: we sketch, we photograph, we write, we record sound and movement. Comparing these media reveals what each conceals. There are things we cannot write, just as there are things we cannot draw—but when we compare drawings, photos, and words, new insights emerge.

Fieldwork also requires critical imagination: the capacity to carefully consider reality and envision how things might be otherwise. It doesn’t directly produce design solutions, but it complexifies the grounding from which design emerges. Interviews with many practitioners confirm that their field methods influence what gets built. Fieldwork, therefore, is not an add-on. It is the groundwork for good design.

William

The book unfolds through reference to various formative moments in your own career. Could you talk about how the role of fieldwork changed over time?

Gareth

My own understanding of fieldwork deepened profoundly during a project in Bahrain. When I arrived at Harvard as a doctoral student, I was frustrated that much of landscape architectural theory was rooted in Western Europe and North America. I wanted to know what design practices meant in other contexts—particularly in the Middle East, where climate, culture, and politics intertwined in different ways.

Bahrain fascinated me. It’s a tiny island—about 700 square kilometers—set in the Persian Gulf, intensely hot, dry, and beige. There, I came across an obsession with creating green space. I wondered: what does “landscape” mean in a place like this?

There was little scholarship to rely on—almost no books on Bahraini landscape, and the profession itself barely existed in the region. So, I decided the best way to learn was to live there. Before going, I prepared by reading everything I could and studying Arabic intensively. When I arrived, I made a curious realization: there is no word for “landscape” in Arabic.

During my fieldwork, I walked the entire island. Walking became my main method. People often stopped me (they were curious, hospitable, offering tea or water) and through these interactions I entered social worlds I could never have accessed otherwise. That’s the beauty of fieldwork: it dissolves barriers, it humbles you, it teaches you to listen. I spoke with residents I met and kept meticulous notes. Over time, I noticed that whenever I used the word “landscape,” people responded with al-khuḍra, meaning “the greenery.” For them, landscape wasn’t an abstract concept; it was a living surface, an expression of cultivation and color.

Through these conversations, I realized how culturally specific the notion of landscape truly is. In Bahrain, “green” signified prosperity, comfort, and political prestige, even though maintaining greenery consumed over half the nation’s water, most of it desalinated. Green space carried huge environmental costs while creating economic, cultural, and political value.

From this project came new research trajectories. One explored color in urban landscapes, culminating in the publication New Geographies 3: “Urbanisms of Color.” Another examined nighttime public space. I realized that most of my photographs were taken by day, even though the life of Bahraini outdoor spaces unfolds at night. Designers, especially in the Gulf, continue to produce renderings bathed in sunlight, yet it’s under artificial light that urban life thrives. Fieldwork exposed this gap between how we design and how people live.

William

The experiences of fieldwork you detail in the book’s chapters, varies widely and are global in perspective. Tell me about some of your projects?

Gareth

The lessons from Bahrain traveled with me—to Brazil, the Caribbean, West Africa, and back to Europe. In Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, for instance, I was part of a team of researchers who asked how landscape architecture could serve communities with minimal material resources. This required expanding our toolbox to include color, texture, and cultural expression.

In one ongoing project (supported by the Lemann Brazil Research Fund), we’re exploring how color might substitute or complement greenery in Brazilian cities. In extremely arid or dense environments, can color achieve some of the perceptual and comforting effects of vegetation? If green carries ecological cost, might a red or blue wall create a similar sense of vitality? These experiments, born from field observation, challenge conventional metrics of “greenness” and sustainability.

Another line of inquiry grew from my fascination with groves. In Bahrain, the palm grove was the archetypal green space. In West Africa and Brazil, I found its spiritual counterpart—the sacred grove. These are places where communities cultivate the energies of nature and the power of ancestors.

Our lab is now studying how this typology might inform contemporary urban forestry in African cities (supported by the Motsepe Presidential Research Accelerator Fund for Africa). Many religious institutions control large parcels of land around churches, mosques, or temples. Could these grounds become urban groves—ecological sanctuaries rooted in local experiences?

To answer this, we’re quantifying land use while also qualifying it—talking with communities to understand their spiritual and cultural relationships to these spaces. Again, fieldwork becomes not just data collection, but dialogue.

And fieldwork plays a role in the Salata Institue project I’m working on with several colleagues including Emmanuel Akyeampong, Daniel Agbiboa, Jerry Mitrovica, and Robert Paarlberg. We’re focusing on the impacts of coastal erosion and urban flooding on communities in the Gulf of Guinea from the Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and Nigeria, where landscape architecture plays a central role.

William

Much of your recent work has taken place in Africa, including the recent conference “African Landscape Architectures.”

Gareth

Yes, that conference took place at Harvard last March. The “s” in “African Landscape Architectures” is very important because it represents a plurality of forms of practice. When we speak of landscape architecture in Africa, we’re including landscape architecture in a formal, professional sense, but also landscape practices that are not necessarily by landscape architects.

Africa is a continent of 54 nations, of which only nine currently have formal landscape architecture professions. In a year of fieldwork across the continent, I visited nearly every school teaching the discipline, and what struck me most was how little African content existed in their curricula. In Africa, students were taught through European and North American cases, not their own landscapes.

At the house of Chief Susanne Wenger and Princess Adedoyin Olosun, in Osogbo, Nigeria. Photo, Moisés Lino e Silva.

Fieldwork convinced me this must change. In the Department of Landscape Architecture, we’ve since integrated African landscapes into our courses, for instance in the core history/theory course I teach with Charles Waldheim. In my seminar on African Landscape Architecture, offered with the Department of African and African American Studies where I have an affiliation, half the students are based in African institutions, joining via Zoom. The aim is not to “teach” them, but to learn together, as equals. Respect for interlocutors is the ethical foundation of fieldwork. By engaging directly with communities, we begin to recognize the complexity of the world rather than simplifying it. This is fundamental for diversifying the landscape canon. Too often, design education seeks clarity at the expense of nuance. Fieldwork acknowledges the complex, layered, overlapping realities that define human landscapes.

William

The prologue to your book describes your early experiences traveling from the Republic of Ireland into Northern Ireland to visit family. This was during the Troubles, and you reflect on how the border created a landscape of tension, exclusion, and trauma. Can such landscapes be reconfigured to become a source of healing?

Gareth

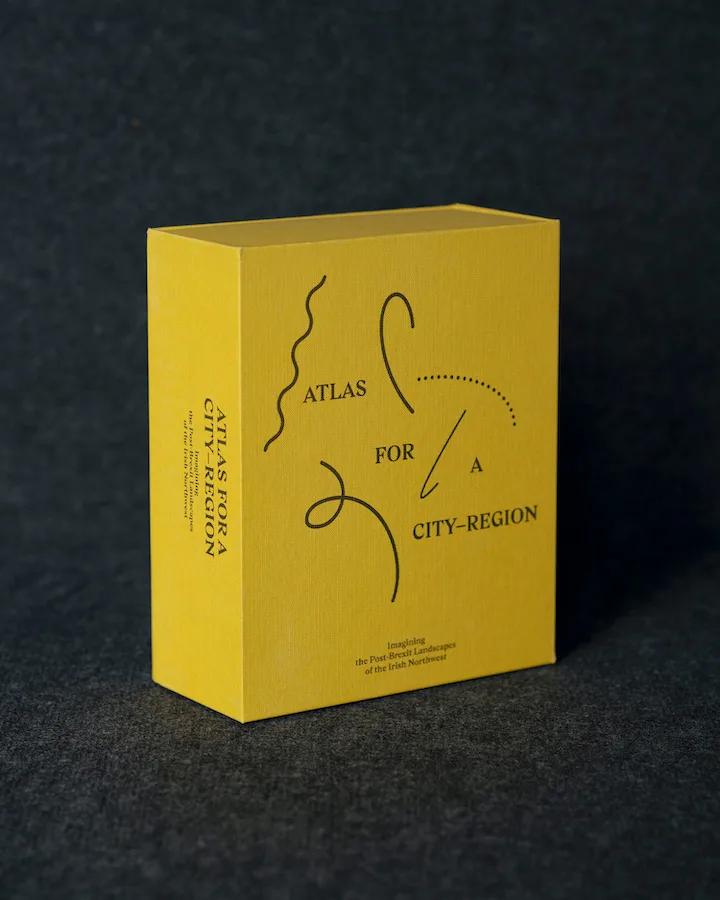

I believe they can—by making difference visible rather than feared. I led a project for the area called Atlas for a City-Region, one of the first major initiatives of the Critical Landscapes Design Lab. It was sponsored by a local governments in Northern Ireland and Ireland and advised both the British and Irish governments on creating a new kind of regional identity between Northern Ireland and the Republic after Brexit.

The governments came to us with a problem: they had endless data on the border—economic reports, and demographic analyses. What they lacked was an understanding of how people actually lived on a cross-border basis. Families lived on one side but sent their children to school on the other. Some worked across, others used the neighboring healthcare system. The border divided, but it also connected; it created what I like to call an informal ecology of exchange.

Atlas for a City-Region, Photo courtesy of Why Not Smile, New York.

Atlas for a City-Region, Photo courtesy of Why Not Smile, New York.

We sent 27 students to live for a week in farms and villages on both sides of the border. They observed, participated, and recorded what they saw. Twelve of those students continued the work in studio, imagining the future of this Irish Northwest region. The governments had two conditions: we had to keep the border visible on all maps, and we couldn’t produce a final “report.” They had enough reports that sat on shelves. Instead, we created a book-exhibition, what we call a “booxhibition,” a dynamic and participatory platform where communities could discuss questions like: Is there truly a region here? If so, how might it evolve over 200 years?

Our ultimate advice to the governments was paradoxical: perhaps we shouldn’t draw the region on a map at all. Maps carry a colonial legacy; drawing boundaries can reinforce other boundaries. Instead, we proposed that the region unfold like our exhibition—on a table, on a floor, in a classroom, or even in a prime minister’s office—an ever-changing conversation.

The project has since won awards, including one awarded at the Consulate General of Ireland in Boston for building bridges between Ireland, Northern Ireland, and the United States. More importantly, it has influenced policy on both sides of the border. Our mantra throughout became simple: “A border is not a line—it’s a landscape.” When you treat a border as landscape, you begin to see complexity rather than opposition; connection rather than separation.

One of the great challenges of our time is the fear of difference. Fieldwork helps reduce that fear. When we expose ourselves and our students to diverse landscapes, we broaden what counts as knowledge. Landscape architecture, after all, has a troubled colonial past. Many African landscapes were designed through the lens of the colonizer. Recognizing that history allows us to craft counter-narratives—new stories that connect people, materials, and ecologies in more symmetric ways.

William

What do you want readers to take away from your book?

Gareth

Looking back, I realize that all my projects—whether in Northern Ireland, Bahrain, Brazil, or places in Africa—are connected by a common concern: landscape is a form of knowledge which needs critical reflection. It’s not just ground or scenery; it’s an accumulation of living practices, memories, and possibilities.

Fieldwork is how we access that living archive. Good design proposals require careful, embodied, and ethical engagements. Research demands patience. But it’s also transformative. To walk through a place, to listen, to be invited for tea, to notice what happens at night instead of day—these are small acts that accumulate into understanding. In the end, fieldwork reminds us that designing landscapes isn’t about imposing our own order. It’s about learning how others have chosen to order the spaces they inhabit and critically imagine better solutions in dialogue. It’s about recognizing that a border can be a landscape, that color can be a form of ecology, that a fountain can hold both colonial history and spiritual renewal. If there’s one lesson I hope students and practitioners take away, it’s this: Fieldwork is not an inconsequential step in the design process—it is the soul of the design process. It is how we learn to see, to empathize,