Obsolescence

Before the built environment is reused it is necessarily rendered obsolete, cleared of prior value and use, in order to graft the new upon it. There is arguably no reuse without obsolescence. It may be illuminating, then, to survey obsolescence’s history and lessons so as to understand reuse’s own genealogy, opportunities, and limits.1

The term obsolescence was first applied in English to architecture about a century ago to help explain the unsettling phenomenon of relatively new American downtown skyscrapers being demolished and replaced. The merely 13-year-old Gillender Building at the corner of Wall and Nassau Streets in New York was rubbled in 1910, brought low by “the influence of fashion, change of habit, competition, development of new territory and shifting of the centres of population and business,” wrote New York engineer Reginald Pelham Bolton in his 1911 book Building for Profit: Principles Governing the Economic Improvement of Real Estate.2

After the Gillender Building’s demise and Bolton’s pioneering book on obsolescence, architectural obsolescence received further attention with the introduction of the US corporate income tax in the 1910s, which included deductions from income for the cost of obsolescence (without specifying exact rates of deduction). The Chicago-based National Association of Building Owners and Managers (NABOM) then set about conducting national membership surveys and “autopsies” of demolitions in Chicago in order both to understand the phenomenon and to support its case for office buildings’ 30-year tax lifespans, that is, an advantageous 3.3 percent deduction taken each year.3 The building owners and managers just about got their wish in the early 1930s when federal tax authorities set office building lifespans at a determinate 40 years.4

Publicized widely in the American press, NABOM’s discourse helped establish in the public consciousness the myth of shortened building lifespans as an inevitable feature of modern life.5 It’s a myth, of course, because buildings don’t magically disappear at 40 years of age. Still, with obsolescence, unsettling change was given a logic and a name, a process of seemingly inevitable innovation, expendability, and progress. It was an architectural analog, in effect, to the idea of capitalism as “creative destruction,” with the new constantly superseding the old. “All that is solid melts into air,” famously proclaimed Marx and Engels.6

In the following decades of the 1930s through 1950s, the idea of architectural obsolescence was extended by urban planners to the scale of the city. In the US, “urban obsolescence” indicated a district’s substandard economic, health, and infrastructure performance, which primed it for demolition and renewal.7 In Europe, the term focused more on social factors, appropriate where the state, rather than private investment, often led development. “In both the Eastern and Western blocs,” writes historian Florian Urban, “obsolescence was the catchword of the time.”8

By the late 1950s, the notion of built-environment obsolescence, in all its contexts, varieties, and scales—from capitalist to socialist, America to Europe, offices to cities—had become a dominant paradigm for comprehending and managing change. “The annual model, the disposable container, the throwaway city have become the norms,” observed American preservationist James Marston Fitch.9

Fundamentally, obsolescence differed from past paradigms of architectural change. Its fast, unceasing ruptures departed from architecture’s traditional ideal of slow, organic development epitomized by the ruinscape.

How did architects respond? At first, with denial. In the 1920s and 1930s, traditionalists stuck to classical forms embodying permanence and durability. Even avant-gardists like Le Corbusier continued to seek “a sure and permanent home.”10 There were exceptions. In Europe, the Czech shoe manufacturer Tomáš Baťa railed against “obsolete houses that will strangle and suffocate the next generation,” and so projected 20-year lifespans for the factories and dwellings of his famed company town of Zlín.11

But it was not until the postwar years of prosperous consumerism that a younger generation of architects faced up to obsolescence’s challenges. In the 1960s, University of London researchers produced in-depth studies indicating, for example, that hospital labs obsolesced faster than patient wards.12 In Japan, the Metabolist group extolled evanescent form-making: “There is no fixed form in the ever-developing world.”13

But it was through design, not words, that architects engaged most deeply with obsolescence. The prime solution was the open-plan factory shed, widely adapted for schools and offices, hospitals and museums. Mies van der Rohe’s New National Gallery in Berlin represented an apotheosis of the type: a perfect frame of infinite interior adaptability created to accommodate a future of endless and unknown possibility.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, 1968. Photo shows the refurbishment done by David Chipperfield Architects, 2021. BBR/Marcus Ebener/ARS, NY.

Other architects, however, rejected the factory shed’s monolithic exterior massing as too static for a dynamic age. Instead they promoted fluid, indeterminate design, like Northwick Park Hospital outside London (1961–1976, Llewelyn-Davies Weeks), the largest British medical complex of its day. Reflecting the research on hospital growth rates, it featured a loose-jointed site plan of demolishable blocks and extendable ends, linked by a longer-lasting internal circulation spine.

Llewelyn-Davies Weeks, Northwick Park Hospital, Harrow, London, 1970. Photo Simon Phipps.

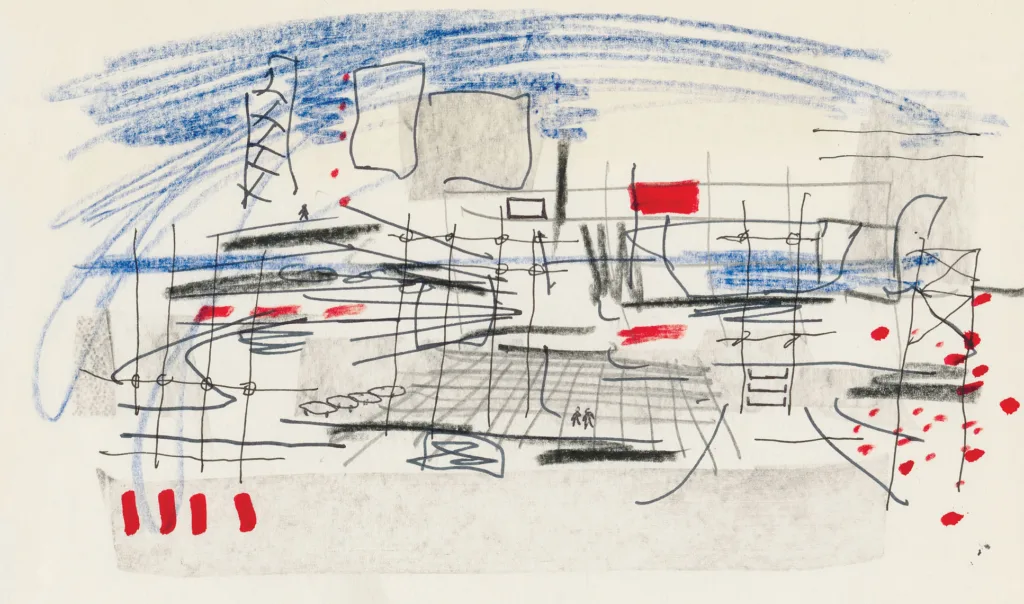

The harmony of permanence and impermanence was the theme, too, of the megastructure—a type associated particularly with Japanese architects—which featured long-life frame and short-life capsule constructions. Metabolist architect Noriaki Kurokawa focused particularly upon imaging the megastructure’s joints—its key detail where the two temporalities, fast and slow, conjoin—in effect, the transition of obsolescence. Plumping fully for obsolescence, English architect Cedric Price echoed critic Reyner Banham in promoting “an expendable aesthetic” and “planned obsolescence,” characterizing some of his own designs, like the unbuilt Fun Palace, as “short-life toys,” replaceable parts in temporary frames.14

Noriaki (Kisho) Kurokawa, Nakagin Capsule Tower Building, Ginza, Tokyo, 1972. Photo Tomio Ohashi.

Cedric Price, perspective sketch of Fun Palace, ca. 1963. Cedric Price Fonds. Canadian Centre for Architecture. © CCA.

During the same period, an impassioned counterreaction to obsolescence also evolved, which refused its logic of competitive performance, rationality, supersession, and expendability. Concrete Brutalism, for example, initiated by Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation, became a worldwide vernacular in the 1960s and 1970s, embodying permanence against obsolescence’s flux—the renewal of traditional expression by Aldo Rossi, Louis Kahn, Robert Venturi, and others, launching postmodernism and revaluing historical imagery. Vernacularism celebrated everyday architecture, which, as Architecture Without Architects, Bernard Rudofsky’s famous 1964 Museum of Modern Art exhibition catalog, proclaimed, “does not go through fashion cycles.”15 Preservationism also witnessed a dramatic upswing in the 1960s, becoming more populist around the globe and incorporating recent and everyday structures. Facilities management emerged during that decade as a distinct profession nurturing building longevity in the face of obsolescence.

Le Corbusier, Unité d’Habitation, Marseille, France, 1952. Photo Thomas Rosenthal. © ARS, NY.

Reuse has been evolving over the decades as a significant ecological strategy, fueled since the 1960s by activists like Jane Jacobs, who rejected urban obsolescence’s wholesale destruction of city districts. In the 1930s, to stem the “ravages of obsolescence,” real estate experts had recommended updating appearances and equipment, an economical option during periods of financial crisis (the 1970s would be a similar moment).16 After World War II, accelerating urban deindustrialization left vast acres of empty factories, mills, and warehouses. St. Louis’s Gaslight Square and San Francisco’s Ghirardelli Square were pioneer developments, converted to shops and restaurants. New York artists, like Andy Warhol in 1964, colonized industrial loft districts for cheap studio space, relishing the patina and grit of the obsolescing environment as they found it. Retail, small business, and residential use followed.

The pace of “adaptive reuse” accelerated in the 1970s; the term was coined early in the decade when the first books were published on the subject.17 By 1978, a third of American architects’ income, it was estimated, came from rehab work. An aesthetics of adaptive reuse emerged. Cavernous volumes were stripped down to bare brick, wood, and iron. Bright new modern partitions, glass enclosures, and ductwork were inserted. Adaptive reuse’s emblematic motif, the exposed brick wall, offered an alternate temporality to obsolescence, a malleable palimpsest, an incomplete erasure of the past—soft change versus the traumas of obsolescence. “Obsolete buildings are fun to convert,” enthused the Whole Earth Catalogue founder Stewart Brand.18

On an urban scale, adaptive reuse has largely meant gentrification, an elevation in an area’s socioeconomic status. British sociologist Ruth Glass coined the term in 1964. But gentrification isn’t purely a capitalist phenomenon. In late 1960s East Berlin, the state abandoned the mass demolition of prewar tenements in favor of rehabilitation in order to husband its resources. “Obsolescence became obsolete,” writes historian Florian Urban.19

Indeed, adaptive reuse under gentrification reverses obsolescence’s architectural logic of demolition, but not its economic and social dynamics. Past investments no longer needed to be destroyed “in order to open up fresh room for accumulation,” as geographer David Harvey would have it.20 In the gentrified city, the fabric remains but the community is cleared out; working-class renters, industry, and small landlords disappear. Gentrification by adaptive reuse may be thought of as the neutron bomb of urban renewal: buildings intact, people gone.

Adaptive reuse was just one counter-tactic among many, all of which we might group under the category of sustainability—with the goal of conserving rather than expending existing resources—which arose against obsolescence in the 1960s. Indeed, the richness of 1960s architectural culture precisely reflected the passions of a contest over obsolescence still then hanging in the balance. The two sides were equally creative and fervid: plug-in impermanence and expendability on the one hand; durability, ecology, and reuse on the other.

But by the early 1970s, the battle was largely over. Designing for obsolescence lost its hold over the cultural imaginary. Top-down, technocratic decision-making alienated popular feeling. Financial constraint in the wake of oil crises dried up resources for endless replacement. Urban unrest eroded public patronage for renewal. Awareness of earth’s fragility underscored obsolescence’s wastefulness. Preservation claimed important victories, as in 1976 when the US tax code began subsidizing historic rehabilitation over demolition. And the UNESCO World Heritage convention, adopted in 1972, continues its global march.

Fast-forward to today, and environmental architecture has particularly come to the fore, prioritizing the conservation of existing resources, first through salvage and then with sophisticated technology, renewable materials, and high-tech systems of energy efficiency. Circular design, based upon ideas about circular economy, represents an extension of environmental architecture, combining old and new, disassembling and reusing materials, optimizing energy and existing resources, in effect, slowing down while accepting processes of gradual change.21 Jeanne Gang, for example, extols mimicking botany with “grafting,” as “a design philosophy aimed at upcycling existing building stock by attaching new additions (scions) to old structures (rootstock) in a way that is advantageous to both.”22

Today it would seem we live in the world the 1970s left us: it’s a world not of exuberant expendability but of careful conservation. In a word, it’s the age of sustainability—arguably today’s dominant paradigm for comprehending and managing change, at least in architectural culture. After all, how many people openly dispute the values of sustainability?

Yet obsolescence endures, even if not as a dominant worldview. In America’s older inner suburban towns, Main Street preservation cohabits with ruthless domestic “teardowns”: the selective obsolescence of postwar suburbia. In China, capitalist modernization today sweeps away the past, echoing the American trajectory a century ago. Nor should we perceive obsolescence and sustainability as completely separate. The relationship between the two is as much filial as agonistic. Obsolescence and preservation, for example, are mutually intertwined. “To expunge the obsolete and restore it as heritage are, like disease and its treatment, conjoint and even symbiotic,” writes historian David Lowenthal.23 Obsolescence and ecological architecture mirror each other, too, in their dependence upon measurable performance. Today’s tables of building energy use echo the data-mania of earlier obsolescence studies. And adaptive reuse can be considered a variation on the megastructure. In both, new components inserted into long-life frames accommodate change.

Obsolescence and sustainability have also both served capitalism well. Obsolescence rationalized and gave a name to profitable processes of early 20th-century wholesale expendability. Sustainability today produces profits through eco-branding and green technologies. And as much as sustainability promises a new, brighter future, can it ever break the current order when its abiding ethic is not radical change but rather continuity, conservation, and an ideal net-zero equilibrium and harmony? Circular economy’s theory, practice, and design may simply strengthen existing power dynamics. It is critiqued as a Western product, technophilic, and market based; deaf to global, Indigenous voices, complex social factors, and alternative political economies.24 In other words, sustainability—no less than obsolescence—is ideological, productive for design to be sure, firing architects’ imaginations as obsolescence once did, but nevertheless rife with illusion and contradiction.

What, then, are some lessons from this architectural history of obsolescence? First, it illustrates the flexibility of capitalism, its capacity to evolve from its own contradictions. What capitalism itself obsolesced—the industrial-age built environment—it then revalued through adaptive reuse, gentrification, and historic preservation. To be profitable again, all that was solid need not melt into air, architectural history teaches us. An architectural history of obsolescence also demonstrates the value in a vibrant architectural culture of the impulses both for accepting extreme transformation and resistance to them. This was the characteristic struggle of the 1960s. Today the impulses stand imbalanced: sustainability ascendant, obsolescence eclipsed. In Hong Kong, at the 2011 Asia Society Center building by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects, a new steel-columned walkway runs at a respectful distance from the massive masonry wall of an old explosives magazine berm. The past is a precious jewel here, set off from present and future.

Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects, Asia Society Hong Kong Center, Admiralty, Hong Kong, 2012. Photo Michael Moran.

Less refined but more instructive, and expressive of the lessons of obsolescence, is the adaptive reuse of a renovated factory building in the Czech Republic. Here in Zlín, a century ago, shoe manufacturer Tomáš Baťa imagined fixed 20-year building lifespans. In 2006, the frame of Building No. 23 was refurbished for adaptive reuse as a business innovation center by Pavel Mudřík and Pavel Míček. It has been added to with a projecting bronze bay. But, more significantly, something has been subtracted from the architecture at the top. To lighten the structure, broad voids appear in the upper floors, thus shrinking the historical frame. Baťa’s intention—a limited-life architecture—is here partially honored. Building No. 23 treats history flexibly, not reverentially. The past is released. The present is open, as implicitly is the future, too.

Pavel Míček Architects and Pavel Mudřík architekti, Building No. 23, former Bata Works renovation, Zlín, Czech Republic, 2006. Courtesy Pavel Míček and Pavel Mudřík. Photo Libor Stavjaník.

Perhaps the most general lesson of the architectural history of obsolescence is that frameworks of change are themselves changeable creations. Obsolescence, then sustainability. Both were invented and can be reversed. Something else may come after sustainability, another worldview for comprehending and managing change in the built environment. One candidate might be resiliency, defined as “the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance.” Like sustainability, resiliency perceives existential threats, but not utopian solutions. And like obsolescence, it accepts a future of constant, radical, unpredictable change.

In any event, a final lesson from the history of obsolescence may be to accept with humility the essential unmanageability of change—the futility of so many efforts to ward off obsolescence in design. The future should be considered as unpredictable, contingent, and potentially as liberating as obsolescence itself. There is much still to learn from obsolescence—in architecture and in our mortal lives: to learn to live with change and to accept, and perhaps even to welcome, endings.

Abramson is the author of Obsolescence: An Architectural History.