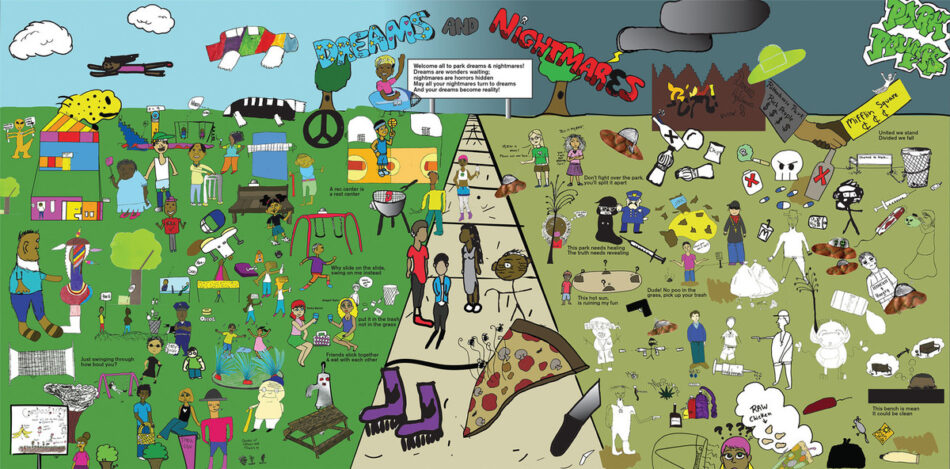

Park Powers

The process that produced the image above grew from a question: What does Southeast Philadelphia have to do to get Mifflin Square Park rebuilt how it wants? Thoai Nguyen, CEO of SEAMAAC (formerly Southeast Asian Mutual Assistance Associations Coalition), used his best hard-boiled organizer approach on a group of teenagers in the park: “We’re a coalition of neighborhood groups trying to get this park fixed. We want you to get the low-down on how that can happen by meeting with elected officials, parks department people, neighborhood groups, whoever has power over the park. Maybe tell them you’re doing a school assignment.” This staged encounter resulted from earlier discussions between our urban design and planning firm, SEAMAAC, and coalition members after they hired us to lead a park design and neighborhood plan.

So in July and August 2016, sponsored by Mural Arts Philadelphia and the city’s summer youth employment program, we worked with 15 teenagers and 3 teaching artists to decipher who has power over the design, operation, and programming of parks. We interviewed construction managers, politicians, maintenance workers, and groups like the Cambodian Association and the Bhutanese American Organization. Below the surface of discussions about garbage pickup, project timelines, and stewardship, our younger collaborators recognized intense debates over the nature of power and place, identity and ethics. Analyzing our encounter with a city official, 15-year-old Paige Scott Cooper wrote: “I remember when Ms. Kilpatrick told us about the budgets . . . [and] about who directs and controls what happens in the parks: why parks in lower-class neighborhoods are like they are, and why parks in upper-class areas are like they are. She knew what to say at times and she was very nervous about some questions. She really made me think there’s nothing the state can do to rebuild smaller communities.”

At the library, we examined historic maps and newspapers to better understand the site’s social textures and ssures (1941: “Youth Shot in New Riot Outbreak”), and thought about building the neighborhood’s park powers. Describing barriers to organizing, 17-year-old Jameira Womack noted: “Most people don’t care about parks in Philadelphia because some of them have better things to worry about. Some of the times people just care about the parks they live around, so they can[’t] care less about other parks. Other people don’t care because they are too busy in their own little world. And a lot of the times people stay in their house so they don’t even bother to go outside.”

At summer’s end, we produced a traveling exhibition of drawings with student-guided tours. In spring 2017, the newly named Mifflin Coalition asked us to incorporate elements of the drawings into a foldout poster in eight languages distributed to every child in seven local schools. Extreme skeptics of the near future, teenagers offer enormous resources for urban designers aspiring to build with roots in organized communities, not least when mocking up divisive practices of spatial management and design mythologies that obscure the social antagonisms that they so expertly observe.

HECTOR is an urban design, planning, and civic arts studio led by Damon Rich and Jae Shin. Recent projects include a memorial for an eco-feminist nun, a riverfront park, a 14-foot city model celebrating the 350th anniversary of the founding of Newark, New Jersey, and an experimental exhibition on mortgage finance. HECTOR’s work has been exhibited at the Queens Museum, the Lisbon Architecture Triennale, and the Newark Public Library.