The Non-Spaces of Medical Tourism

I spent the last six years as a strange kind of tourist. I traveled the globe visiting hospitals. Not just any hospitals, but those participating in the “medical tourism” industry—a booming multi-billion-dollar business based on international travel for the primary purpose of receiving health care in places like Thailand, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, India, and Singapore.

The United States has long been a hub for in-bound medical tourism—our best hospitals have always attracted the global rich—but an increasing number of Americans are now traveling abroad for gastric bypass surgery, hip replacements, cosmetic surgery, sex reassignment surgery, cardiac bypass surgery, and many other procedures. In addition to these South-North and North-South flows, there are South-South patient flows (e.g., Yemenis traveling to Jordan, or Indonesians to Malaysia), as well as North-North flows (e.g., Canadians coming to the United States to jump the queue, or the robust inter-EU cross-border health-care regime now enshrined in law).

The motivations for becoming a medical tourist are diverse. Some travelers have universal health-care coverage but go abroad to avoid a waiting list. Some patients are uninsured or underinsured and pay out of pocket for procedures, saving as much as 80 to 90 percent of their costs. Some procedures are unavailable at home or certain foreign practitioners might be viewed as more skilled than those at home (Thailand, for example, is highly regarded for its sex reassignment therapy). Some privately insured patients’ employers incentivize employees to travel by waiving a deductible or a copay or even giving the patient a check—ABC News recently reported on a North Carolina patient who faced $3,000 in out-of-pocket costs for gastric bypass surgery, ultimately accepting her employer’s offer to fly her to Costa Rica for the surgery at zero cost and a bonus check for at least $2,500—just a fraction of the cost savings for her employer. Yes, you read that right, this employee actually made money by traveling to Costa Rica for her surgery.

My travel was not for medical ends, but for research. Some of my visits were part of “fami tours” (short for familiarization) built into promotional conferences organized to sell the hospitals as destinations for medical tourism; on other occasions I ventured out on my own to observe an average day at a facility. These visits were not always warmly welcomed. On one memorable occasion I was met by a security guard who saw me snapping photos, demanded I delete them, and hovered over me to ensure I did.

As I wandered through endless halls, I was struck by how their design reflected what the destination hospitals perceived as our (i.e., foreigners’) desires and hopes. Like airports, which exist “outside” geography, these hospitals are defined by the services they provide rather than their physical and social contexts.

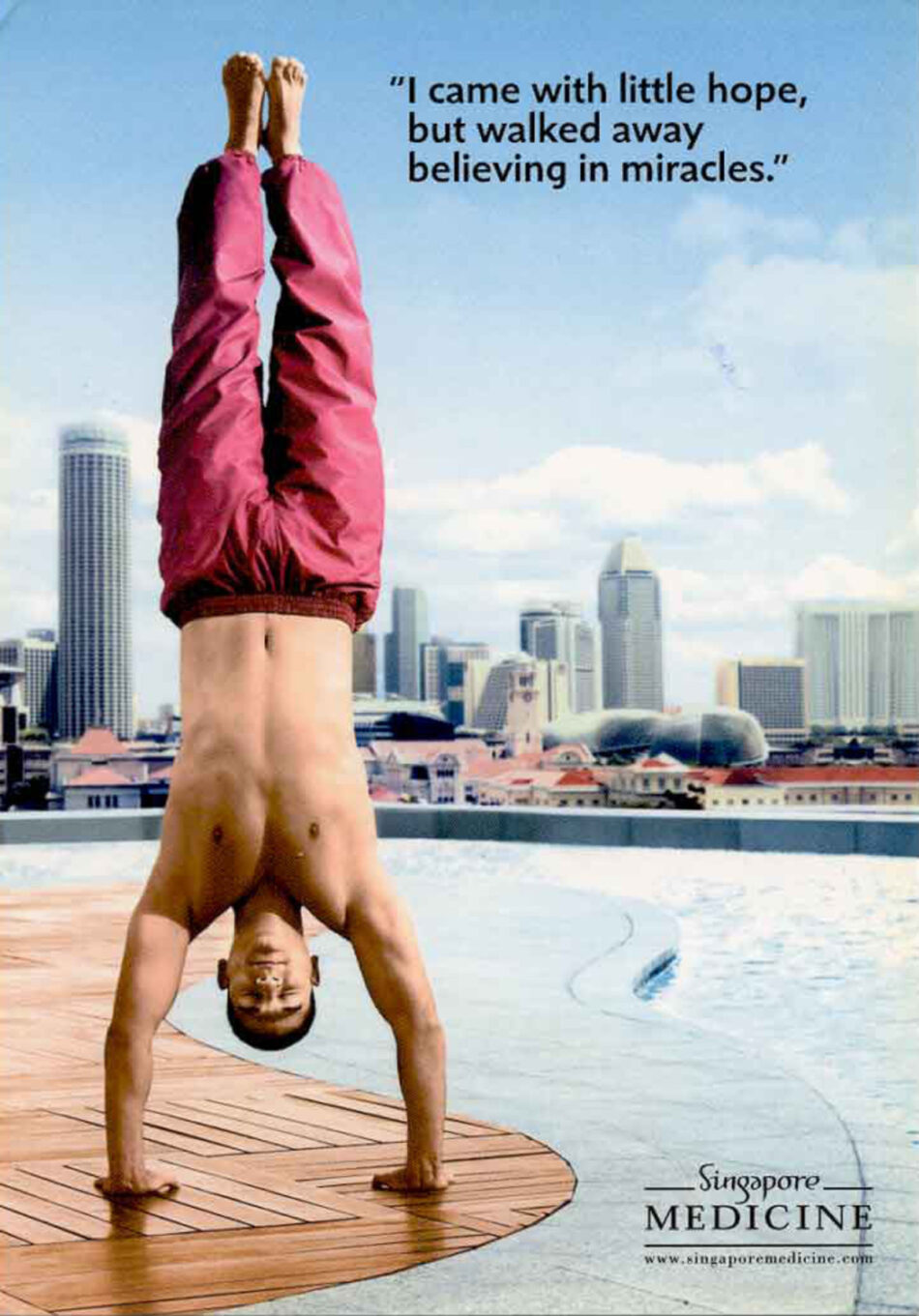

Most major destination countries—such as India and Thailand, two leaders in the field—have a handful of premiere hospitals groomed to attract foreign patients. Those hospitals routinely mirror the look of prominent American hospitals in their design. Imagine something like Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) (top-rated in the United States and one of the world’s largest research hospitals), with its gleaming glass windows, impressive entryway, futuristic lighting, pristine walls and surfaces—a decor that reflects the grandeur of high-end modern hotels with a certain primness. Walking into the Bumrungrad International Hospital in Bangkok, for example, is like entering a Marriott conference hotel with a science vibe. Others like Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong in Seoul match the MGH image. Both, like most US hospitals, are places of sterility, transience; environments for scientific expertise, not community or home. They are liminal non-spaces; one could just as easily be in New York, Seoul, or Bangkok.

As I dug deeper, healing culture began to disambiguate itself. Kyung Hee, like many East Asian hospitals seeking to attract Westerners, brands itself by emphasizing the way it unites Western and Eastern medicine. There, I encountered something I have never seen in the United States: a room

devoted entirely to brewing tea, where each tea is individually concocted according to the ailments of a particular patient. I also came across semiprivate acupuncture rooms containing a tangle of wires hooked up to a power source and needles—much more mechanized and electrified compared to what is common in the United States.

When I left the premiere hospitals and traveled farther afield, I found a different vision of the hospital. I went to Mawar Renal Medical Centre, in the Negeri Sembilan region of Malaysia, a charitable hospital that focuses on renal dialysis. Mawar is expanding, and seeks foreign patients to supplement its income and sustain a larger physician and nurse workforce that could also serve the local populace. There, medical care was much homier. Gone were the gleaming halls of science, replaced with an exterior that looked more like an apartment building in a tropical climate—fitting, in that it offers on-premise hotel services to patients’ families. I visited during the Hindu festival of Diwali, and the dialysis room was made festive with paper garlands. As I walked through the halls, I saw themed waiting rooms catering to Malaysia’s diverse cultural communities: for Buddhists there was a modest room with Zen accoutrement; for Hindus a sand mosaic celebrating Diwali; and for Westerners, oversized furniture in faux gold leaf and outrageous patterns meant (I think) to signal luxury. It was here, draped over a kingly crimson divan, that I finally understood: in these spaces we see the hospital’s assumptions of what it is we want, ourselves reflected through a mirror, not a glass, darkly lit.

But more interesting than what I could see at these hospitals, was what I could not see. I am not a trained physician or nurse. Seeing the various operating rooms, cancer centers, and MRI machines, I had the usual sense of awe at the power of medical technologies, but I had no idea if what I was seeing was medicine practiced well. This is the plight of the typical medical tourist. While there are markers of excellence for destination country hospitals—the number of health-care practitioners educated at familiar (read, Western) medical schools or accredited in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, etc.; or whether the hospital has international accreditations like the Joint Commission International—none of these are that good a proxy for health-care quality. Having these things is better than not, but given the heterogeneity of care quality, these markers are not sufficient guides. What one would really want—robust risk-adjusted and comprehensible morbidity and mortality data—is largely unavailable to the individual medical tourist.

Here, too, though, in some ways the industry is showing us a mirror of our desires. Even when seeking care within the United States, we routinely ignore quality health-care data in favor of anecdotal reports, which are no doubt influenced by aesthetic considerations. For example, in 2000 the Kaiser Family Foundation surveyed 2,014 adult Americans and found that only roughly 10 percent had used information comparing quality among health plans, hospitals, and doctors, when available, and that in making provider selections, respondents favored recommendations from friends, family,and other doctors over actual data on health-care quality.1 More generally, the literature on patient selection of hospitals and physicians paints a bleak picture that emphasizes doctors’ reluctance to help patients make choices as health-care consumers, patients’ failure to understand health-care delivery and statistics, patients’ tendency to avoid making medical decisions, and patients’ fixation on cost over quality.2 In failing to give us more robust data, perhaps the industry is again reflecting our own desires as much as shaping them.

Sustainability, Inequality, and Medical Tourism

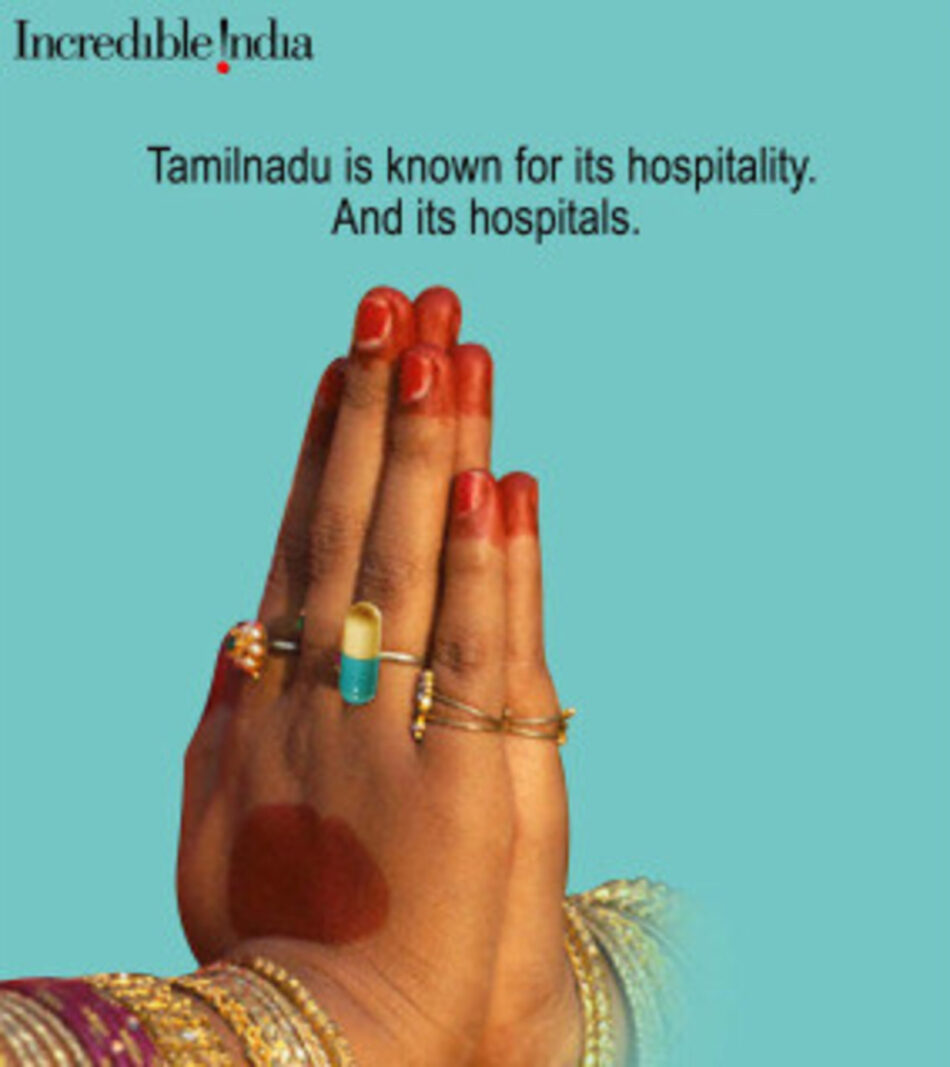

The industry also reflects our desires to see and not to see in a different way. Hospitals often emphasize themes of luxury, recuperation, and cultural experiences: an Indian medical tourism package will often pair a procedure with a trip to the Taj Mahal, a Caribbean one with time at a spa and the beach. The industry Disneyfies the destination country and largely exposes the patient to a version of the country and its culture that does not reflect the full reality. In this way the tourism part of medical tourism (and why I resist calls to shift to the nomenclature “medical travel”) is real, intentional, and part of what the industry is selling.

The result is an obscuration of the inequality between the health care experienced by the medical tourist and that of the destination country’s general population. Take, for example, the case of Mr. Steeles, a 60-year-old car dealer from Daphne, Alabama, who, according to a New York Times article, “had flown halfway around the world last month to save his heart, at a price he could pay” at Bangalore’s Wockhardt Hospital. The article describes in great detail the dietician who selected Mr. Steeles’s meals, the dermatologist who came as soon as he mentioned an itch, and his “Royal Suite” with “cable TV, a computer, [and] a minirefrigerator, where an attendant that afternoon stashed some ice cream, for when he felt hungry later.” This treatment contrasts with the care given to a group of “day laborers who laid bricks and mixed cement for Bangalore’s construction boom, who had fallen gravely ill after drinking illegally brewed liquor […] more than 150 died that week.” The article’s author writes, “Not for them [was] the care of India’s best private hospitals. They had been wheeled in by wives and brothers to the overstretched government-run Bowring Hospital, on the other side of town. Bowring had no intensive care unit, no ventilators, no dialysis machine. Dinner was a stack of white bread, on which a healthy cockroach crawled.”3

That the industry obscures inequality is no surprise; most of our travel experiences do that. What is more worrisome is the way in which medical tourism threatens to cause or worsen disparities in health-care access for populations of destination countries. The people I talked to and the development literature has stressed four primary mechanisms through which this may take place (though each country is unique): (1) The health-care services consumed by medical tourists are provided by resources (hospitals, physicians, nurses, etc.) that would otherwise be available to the destination country poor (and in many cases even the middle class) for their health-care needs. This might include the destination country government directing resources away from basic health-care services or public health initiatives to medical tourism in a way that does not have positive spillovers for the destination country poor. (2) Rather than serving some tourist clientele and some of the existing population, health-care providers and resources are thus “captured” by the medical tourist patient population, and the supply of health-care professionals, facilities, and technologies becomes inelastic. (3) Many argue that the industry creates a buffer for the destination countries, counteracting a potential “external brain drain” of health-care practitioners to foreign countries. But these positive effects may be outweighed by the lack of availability of health-care resources for local populations (including “internal brain drain” from public to private hospitals). (4) Profits from the medical tourism industry are unlikely to “trickle down,” because of many countries’ tax structures. Often the development of a medical tourism industry in a destination country is the work of a partially or fully foreign-owned corporation.

While traveling with health geographer colleagues in Barbados, I trekked through an abandoned hospital rumored to be a possible redevelopment site for American World Clinics, a venture that seeks to bring international physicians to Barbados in a time-share model, wherein they see their own patients at a fraction of the cost. The old hospital was in ruins, concrete reclaimed by the local foliage, with remnants of the last days of practice (a hospital chart, an IV pole, a crib) frozen in place like Pompeii’s last day. Given the financial structure of the project, if the clinic is established it would certainly bring benefits (employment, purchases) to Barbados, but it is unclear how much of the corporation’s profits (or taxes) would be reinvested in Barbados itself.

While the evidence is still not complete, there is reason to worry that medical tourism may, for these reasons or others, end up making health-care access worse for some destination countries’ populations—its poor in particular. But such a result is not inevitable. What is needed is regulation and consumer advocacy (akin to the fair trade movement) to help make the industry one that takes sustainability seriously.

When private insurers encourage patients to go abroad for treatment, the home country could require by law that employers/insurers only send patients to facilities or destination countries that have taken meaningful steps to ensure health care for the poor. It could also consider taxing insurers using medical tourism by the volume of patients they send and using the revenue toward targeted aid or capacity-building projects.

Prominent foreign hospital accreditation agencies, such as the Joint Commission International, should be pushed to build analyses of negative effects and ameliorative action taken into their accreditation requirements. Home and destination countries must nudge these accreditors into taking these steps, for they are unlikely to do so on their own.

Destination country governments can tax medical tourism providers and redistribute the proceeds to pay for health-care access to the poor by investing in health-care or public health infrastructure. They can attempt to ramp up the production of physicians and nurses, and use techniques such as conditional scholarships to retain them. They can also regulate the behavior of their physicians and other health-care workers and require that they spend certain amounts of their time serving domestic rather than foreign patients (who usually pay higher prices). They can require a uniform reimbursement rate to blunt the incentives of local hospitals to take on foreign patients instead of domestic ones as a way of improving revenue stream and the like. For destination countries where certificates or other licensure are required in order to build a new hospital or expand an existing one, the government can limit the number of entrants into the medical tourism market that exists or extract commitments (such as those pertaining to providing care for indigents) from the facilities. That said, in India and other places where some of these regulations already exist, they have proved something of a paper tiger. There, reports suggest that some hospitals have failed to honor commitments to the state to reserve a certain number of beds for citizens.

Finally, individual medical tourists are not without their own power to push the industry toward more sustainability. They are often ill, and sometimes driven to look for options abroad due to poverty or lack of insurance, but that does not absolve them of responsibility for the effects of their choices. First and foremost they have a duty of inquiry to understand what effects their medical tourism has on the destination country poor and what amelioration plans are in place. Second, they need to understand that this choice, like all consumption choices, is a moral one, not merely an economic or pragmatic one.

These kinds of steps, from an ethical perspective, will help transform medical tourism hospitals from non-spaces into real spaces rooted in active communities. As users of these services we are not merely “passing through” as in an airport, but instead are engaging in a practice that is deeply embedded in and having significant effects on real communities. When we can see the practice for what it really is, we can both enjoy and appreciate the opportunity for an authentic relationship with a culture and a community; but, at the same time, it makes manifest that we are engaged in a practice that raises deep ethical questions about how well we are acquitting our obligations to those whose resources we are using.

I. Glenn Cohen is Professor of Law and Faculty Director of the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at the Harvard Law School. His work has been widely published in law and medical journals; he is the author, editor, or coeditor of several books, including Patients with Passports: Medical Tourism, Law, and Ethics (2014).