Ukraine in Times of War: Reconstruction as Strategy, Tactics, and Practice

Russian aggression against Ukraine began with the occupation and annexation of Crimea in 2014 and escalated into a full-scale invasion in February 2022. While destruction continues, efforts to rebuild are already underway. The following conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, focuses on emerging practices of reconstruction in Ukraine—practices being forged in the midst of ongoing war.

The biggest challenge in planning Ukraine’s recovery is responding to the vast scale of destruction and displacement. Providing shelter, care, and community for hundreds of thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) is urgent. But reconstruction must also grapple with long-term imperatives: developing planning strategies rooted in sustainability and resilience, especially strategies for mitigating the effects of anthropogenic climate change. Even before the war, Ukraine had the most energy-intensive economy in Europe. These circumstances raise fundamental questions about how architecture, urban design, and planning can respond effectively under conditions of profound instability and change. How can they combine rapid response with long-term vision, integrating the strategic, tactical, and practical modalities of war in the project of reconstruction? What specific strategies, tactics, and practices will help designers and planners respond effectively to crises of this magnitude?

Our panelists engage with the built environment in Ukraine from a range of perspectives, expertise, and organizational settings—NGOs, architectural practices, universities, and municipal agencies—working across the diverse regional and urban contexts of Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Kharkiv, and Chernihiv. They include Oleg Drozdov (founder, Drozdov&Partners, and cofounder, Kharkiv School of Architecture), Anastasiya Ponomaryova (architect and cofounder, Urban Curators and CO-HATY), Anton Kolomeytsev (chief architect, Lviv), Sergiy Bezborodko (head of the board, Eco Misto Chernihiv), Oleksandr Shevchenko (CEO, Restart Agency), and Iryna Matsevko (historian and vice-chancellor, Kharkiv School of Architecture). Our discussion here extends a long-running dialogue that we’ve continued as part of two courses I taught at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 2024 and 2025.1

—Eve Blau.

The National Academy of State Administration of the President of Ukraine destroyed by the airstrike, Kharkiv, March 18, 2022. © Jerome Sessini/Magnum Photos.

Eve Blau

I want to begin with Oleg because we’ve been having an ongoing conversation about these issues. You cofounded Roзkvit2 and the Kharkiv School of Architecture.3 But first and foremost, as a founder of Drozdov&Partners, you are a practicing architect, so the questions that I would like to start with are concerned with practice. After the full-scale invasion started, you moved your practice and the school to Lviv. What’s changed in your practice since the war started? Ukraine will have to make critical choices given the demographic situation, the state of the built environment, and the climate emergency. How do you see architecture’s agenda in Ukraine evolving, and what will it face after the war?

Oleg Drozdov

Even though I’m experienced in being a displaced architect and educator, this is a completely new environment that we are still in the process of shaping. Since the start of the war, the nature of my practice has changed completely. At first we couldn’t imagine how we could continue working. But then we began designing temporary shelters to provide for the basic needs and dignity of the IDPs. After that, we started working on social housing: first in Lviv, following a national competition for IDPs and patients of the UNBROKEN rehabilitation center.

For me, and for everyone who is now fighting, there’s a clear vision of the future: the formation of a democratic society within the European Union. It’s important to start embedding the values of this future in all of our practices. The role of the built environment is critical. But we are still developing the strategies, processes, and methodologies for its transformation.

We’re facing wartime challenges as well as climate, social, and demographic issues. We will have to think much more comprehensively—we need to identify opportunities in our shrinking cities, reconstruct them in a more people-centric way, give certain territories back to nature, and find a new relationship with the environment. Moderating these processes will be part of architects’ new role.

Eve

You make important points about the conditions of practice in the midst of war and ongoing destruction: the need for an immediate response, the need to act quickly and decisively, and to innovate, while never losing sight of the long-term; the need to reimagine and construct an alternative future. What is the role of architectural education in these processes?

Oleg

We lack several professions necessary to build and reshape a future Ukraine. Urban planning, generally, is not recognized as a profession. We don’t fully appreciate the capacity of urban design or landscape architecture. We don’t have much experience with architects interacting with the community. This imbalance between our future needs and our capacity has to be partly addressed with digital technology. It will require serious work to transform the industry and its design tools. Architectural education is key to this transition—to educate practitioners capable of envisioning and realizing large-scale transformations of the built environment, and to foster a more community-minded way of understanding the city as a whole.

Eve

You and your colleagues at the Kharkiv School of Architecture have begun that work to reshape architectural pedagogy in order to tackle the large-scale urban and environmental tasks of reconstruction. Now l’d like to turn to Anastasiya, who is also engaged in developing new modes of urban architectural practice. Anastasiya, you’re an architect who is deeply involved with several Ukrainian NGOs that are linked to urban development. The CO-HATY initiative, for instance, provides temporary accommodation to IDPs in western Ukraine. Together with your colleagues, you’ve successfully applied the principles of adaptive reuse to these projects. This speaks to the importance of rapid response, of acting as an architect, and addressing the experience of displacement with design solutions that provide connection and community. It also resonates deeply with humane and social design principles. Could you talk about that work?

Anastasiya Ponomaryova

I believe that the refurbishment and adaptive reuse of vacant spaces has a magnetic, powerful effect. It is a comprehensive instrument that allows us to address social and spatial issues simultaneously. We aim to make both the design and the construction process as inclusive, joyful, and practical as possible.

Throughout the refurbishment process, we experiment with the balance between professionals and nonprofessionals, internally displaced persons and host communities, and their long-term and short-term needs.

We have mobilized more than a hundred volunteers around the CO-HATY idea, some of whom are still working with us. As an interdisciplinary organization, CO-HATY benefits from that diverse knowledge and from the team-building aspect of these experimental refurbishments. We started the process as architects driven by ideas about circular economy, but in this collective work we’ve also made good progress toward social inclusion and skills empowerment.

We’ve learned that, in the humanitarian sphere, we had underestimated the importance of the quality of architecture. Honestly, people don’t stay in a shelter that doesn’t look nice. The practice of adaptive reuse advances the standards of humanitarian architecture, and brings together the energy and dignity of those who build with those who use these spaces.

Eve

Can these become peacetime practices, part of a long-term strategy?

Anastasiya

Adaptive reuse is a good approach to housing IDPs because it can deliver very rapid solutions. But it’s also a sustainable approach for any situation, not only for emergencies, as it promotes the principles of circular architectural practice. The real difficulty is scaling up—how to go bigger.

After seven successful projects for short-term housing, mostly in the Ivano-Frankivsk region, we’re now developing a mid-term housing typology, in the Vinnytsia region, still using adaptive reuse as our approach. This involves experimenting with planning regulations and restrictions. If we succeed, I will share with the world that it is possible to advance refurbishment as a long-term strategy.

Eve

The experimentation with planning regulations is exceptionally interes- ing and consequential for the realization of adaptive reuse design methodologies at scale. I would like to bring Anton into that discussion. Anton, you’ve been the chief architect of Lviv for the last five years. You studied and worked at the Lviv Polytechnic and have a deep connection with the city. Unlike the eastern parts of Ukraine, Lviv has been spared from extensive shelling and damage to its built environment. But since the beginning of the war, millions of people have passed through the city on their way to other places in Ukraine and abroad. A number of them have also found refuge and have stayed in Lviv. We know that the city immediately started constructing emergency housing for IDPs. How has the city integrated this new population? How has the war influenced city planning practice and processes? What kind of integrative and innovative work is being done?

Anton Kolomeytsev

Yes, we are one of the safer cities in Ukraine, but there are no safe cities in a country at war. We have almost 40,000 men and women on the front line, so everybody has friends or relatives who are there, and you can feel that everywhere.

From time to time, there are deadly missile and drone strikes. The damage is repaired quickly, and you cannot really see many physical traces of war in the city. Cafés and restaurants are open, and kids go to school. It is very good that there is an economy, a life that goes on. At the same time, every day there are commemorations and funerals for fallen soldiers. Urban life changes dramatically when the entire main square is full of people participating in these ceremonies.

Five million people passed through Lviv after the Russian invasion in 2022. All of our houses were full of people in the first weeks and months of the war. Now, there are about 150,000 IDPs in Lviv. Many of them have bought or are renting private apartments or live with relatives or friends.

Since the first days of the war, we have understood that we needed to adapt all the municipal buildings, sport halls, schools, and even office spaces for temporary living. There was also a need for emergency temporary housing. Polish colleagues helped us with shipping containers, like those used in Germany to house Syrian refugees, but we had to come up with a good spatial program for installing them. Even for short-term stays, people need good community spaces, playgrounds, and sports fields. We installed these campuses of temporary housing for up to 1,500 people, not out in the fields but directly in the neighborhoods of the city to integrate them with local communities.

During the war, Lviv became the biggest humanitarian hub in Ukraine. We founded a municipal project, Unbroken, to provide physical rehabilitation and mental health care for the wounded, and to support retraining and job placement for them. We renovated a seven-floor hospital from Soviet times into a modern rehabilitation center, with support from partner cities, companies, and the German government.

We also stopped selling municipal land. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, no new permanent municipal housing was built, so we decided to use this land for housing to support wounded people and others in need.

Modular town that houses 1,400 IDPs, Lviv, 2023. Photo Pavlo Palamarchuk/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images.

Eve

So, you are building municipal housing on city-owned land. Can you tell us about the new technologies and systems that you’re experimenting with?

Anton

We started experimenting with timber construction soon after the full-scale invasion began. We constructed a housing complex entirely from timber, called Unbroken Mothers, for pregnant women and families with small kids. In 2022, Shigeru Ban visited Lviv and provided his famous paper partitions to use for emergency shelter in our sport halls. He also visited the hospital and learned about the crucial need for a surgical center. A few months later he called me and said, “I have an idea for doing it in timber. If it is okay, I will do the project, and you’ll see if you can build it.”

UNBROKEN Mothers, Lviv, 2022. Courtesy UNBROKEN Mothers.

He started working with local architects, and now we have the project ready and we’re finalizing the finances. The project consists of 25,000 square meters across six stories with prefabricated timber elements. Even the joints are without metal. The same structural engineer who worked on Shigeru’s Swatch and Omega campus worked on our building. This is a great source of knowledge for local architects.

In preparation, we built the Superhumans Center, a prosthetics factory, in half a year, and two additional floors on an existing three-story hospital, all in timber. Now we’re ready to deal with all the regulations to build such innovative projects. One can say that during wartime you can build with anything you want, that you are in a state of urgency. But we also understand that we must innovate with every project. We can’t say, “We’ll innovate tomorrow.”

Eve

This project is a perfect example of the ways in which experimental practices that are emerging in response to the urgent need for housing and care are pointing the way forward for the long term, not only for Ukraine but for design and construction practices more generally. Wartime reconstruction practices are also generating new methods for shaping urban public space—building community. Sergiy, this is the space in which you are working. You’re the founder of Eco Misto Chernihiv, an initiative aimed at improving the quality of public spaces in the city. Can you describe the situation in Chernihiv, and talk about the importance of public space in times of war? What projects are you involved in? What have you learned from them, and how do you see that process continuing into peacetime?

Sergiy Bezborodko

I’m an activist and practitioner who always tries to implement what I read, from Jane Jacobs to Mike Lydon. I strive to build community. Early on, using methods from tactical urbanism, we worked on revitalizing the old campus of Chernihiv Polytechnic National University—we renovated abandoned spaces and transformed wastelands into allotments for urban gardening. Before the full-scale invasion, we also operated the first and only garbage sorting station in the city. Chernihiv is located 80 kilometers from the Russian border, so when the full-scale invasion began, the city was under siege within three hours. It was heavily shelled but soon liberated. We lost our workshop and equipment, but we still had our community. We started to rethink our projects, shifting our role as “garbage activists” to bicycle couriers. With public transport at a standstill, we started delivering food, medicine, and essential supplies to the elderly. Every crisis creates an opportunity for change. For example, we were able to show residents why the bicycle is a great mode of transportation, not only during war. Since then, we’ve repaired more than 700 bikes donated from Europe and given them to social workers, volunteers, medics, and IDPs.

Eco Misto Chernihiv, Go Bike, a volunteer delivering humanitarian aid by bike, Chernihiv, 2022. Courtesy Eco Misto Chernihiv.

I also lead the Center for the Development of Startups and Innovation at Chernihiv Polytechnic. We are revitalizing the old university cinema into an innovative public venue with workshops, fabrication labs, and public spaces. We also improved the public space in front of the cinema. We involved neighbors in the planning and invited architecture students to help. We removed hundreds of concrete bricks to free up more green space, built street furniture using old pallets, planted trees and bushes, and created art compositions.

Another of our projects is plastic recycling. We created the brand Plastic Fantastic within the Peremoha Lab, where we have a shredder for crushing plastic, a thermal press, an injector, and an extruder. The ability to transform waste into new products to support our army and our efforts inspires people. I feel that this experience helps unite us and increases the trust among people. It is important not to wait but to act—to do what we can, with what we have, where we are now.

Eve

The work you are doing is striking for its agility and capacity to respond to continuously shifting needs of multiple constituencies. They are small interventions with significant impact and agency to improve the quality of everyday life, to sustain community. Oleksandr, you are also working with communities, and have collaborated with Sergiy in Chernihiv, but you are working at a territorial scale and through the complex administrative networks of municipal planning. Your background is in spatial planning, engineering, and urban studies. You’re the founder and CEO of the Restart Agency, which primarily works with municipal authorities to produce integrated development plans. Can you tell us about your methods and particular projects, and how you address immediate issues while simultaneously thinking about long-term strategies?

Oleksandr Shevchenko

We work with local administrations, the national government, and international organizations for technical support. Before the full-scale invasion, we were trying to identify the specific challenges facing the hromadas [municipal authorities] and respond to them either with integrated plans or through specific projects and interventions embedded in those plans. However, the war has significantly accelerated and complicated this process. Now, our agency is working on bringing pragmatic and contemporary practices of spatial planning into planning documents that sometimes look quite frightening.

We’ve been learning by doing. Our first project with Chernihiv and Sergiy resonates with some of Anastasiya’s experiences. We explored how spatial planning could serve as a foundation for integrated and consolidated recovery efforts. We identified specific issues facing the hromadas and proposed various approaches to secure international funding. Currently, there’s a lack of coordination on both strategic and tactical levels. Sometimes great initiatives are not coordinated, or a single hromada might simultaneously develop several strategic spatial documents with different organizations.

We need to find pragmatic and rational ways to implement short-term and mid-term planning and project execution. Lviv is a good example of how that can be done, though not all hromadas have the same level of resources or capacity.

The reality is that we are in an environment that is changing every day, with new norms, ongoing shelling, and the continuous movement of IDPs. And local developments are not always considered on a strategic level.

View inside the Kharkiv Regional Palace, which was heavily bombed and shelled by Russian forces, March 2022. © Jerome Sessini/Magnum Photos.

Eve

Conditions of uncertainty and instability create particularly intractable problems for spatial planning at territorial scale, which is predicated on being able to take the long view—to plan. What about historic preservation? Iryna, you’re a historian with a focus on questions of public history and built heritage. Has there been extensive damage to architectural heritage? How has the war changed the appreciation of heritage, or impacted practices of preservation and heritage studies?

Iryna Matsevko

Some call this “the heritage war.” For Russia, the targeting of Ukrainian heritage serves as a means to erase Ukrainian identity and as a justification for invading the territory of an independent state.

The war has had a significant impact on Ukrainian cultural heritage, transforming our perception of it from a passive legacy into an active symbol of resistance. It now serves as a unifying force for Ukrainian communities. We have come to understand that by protecting our heritage, we are not only protecting our past but also defending our present and ensuring our future. The war has raised crucial questions about how to balance urgent responses to threats to heritage with long-term strategies for heritage preservation.

There are numerous grassroots initiatives and local institutions documenting heritage that are supported by domestic and international grants and programs. There are also discussions on how to turn these short-term initiatives into long-term strategies for heritage preservation and how to build sustainable networks between local institutions and international heritage bodies like UNESCO or ICOMOS [International Council on Monuments and Sites].

Eve

How is the Kharkiv School of Architecture addressing these issues? Can you tell us about your current project, “Architectural Heritage Preservation in Times of War: The Ukrainian Model”?

Iryna

Our school has revised our educational program in response to the challenges posed by the war. We’re working on a new course in partnership with international institutions, and within the framework of international projects—for instance, “UREHERIT: Architects for Heritage in Ukraine; Recreating Identity and Memory.” This course teaches students to analyze the social, political, and cultural contexts of heritage, to gain an understanding of different heritage discourses, and to develop skills in participatory practices for working with local communities. We see an important role for architects in conceptualizing heritage as an essential part of integrated community development plans.

“Architectural Heritage Preservation in Times of War: The Ukrainian Model” is a project focused on developing the skills of heritage conservation and documentation. In cooperation with the Heritage Management Organization and Skeiron—the leading Ukrainian organization for 3D documentation of built heritage—we are designing and delivering courses on architectural documentation, conservation assessment, and heritage analysis. As part of this project, our students will produce 3D surveys of 30 heritage sites in western Ukraine. The initiative will also offer courses for teachers and PhD students at architecture schools across Ukraine, enabling them to establish their own courses on conservation and documentation.

International cooperation with various institutions in Europe and the United States helps us fulfill our social mission of training a generation of architects who will rebuild Ukraine, equipping them to work in various contexts on conservation and reconstruction, and preparing them to make complex and difficult decisions about heritage.

Anastasiya

I would like to add one point to Iryna’s discussion of heritage: CO-HATY deals with everyday or ordinary heritage, and we believe that through refurbishment we also contribute to local history and identity. However, in order to construct new residential complexes, developers in Kyiv are demolishing important parts of our national heritage. I think it is brutal to purposefully destroy heritage for profit at the same time that the Russians are destroying heritage as part of their military strategy. People are asking the authorities to stop such demolition, comparing the Kyiv administration’s actions to Russian missiles.

Eve

Oleg, we’ve heard about future plans and current initiatives in Lviv, Chernihiv, and Ivano-Frankivsk. What about Kharkiv in the postwar context? The city is close to the Russian border and has been badly destroyed. How do you see its reconstruction?

Oleg

This is a painful question because we were an active part of the Kharkiv community for a long time. Kharkiv has been declining since independence, and during the last decade it has struggled to define a new role for itself. Even before the war, it was a big, unfinished project—a partial realization of several utopias—with enormous possibilities. If you’re asking about scenarios for its future, everything is possible. The history of Kharkiv is that of a city of huge ambition located in the middle of nowhere. Despite its geographical position, it was the industrial, engineering, and design capital of Ukraine—built entirely on people and ideas.

I worry about who will undertake its reconstruction, how we can attract a new generation of change agents there, how to develop responsibility within the community, and how people with expertise could be involved in this project. I’m jealous of how Lviv built an expert community and implemented an organized decision-making process. Kharkiv’s recovery has to evolve naturally, but strong institutions should also be involved from the start.

Eve

I’d like to change gears now and ask two questions. The first is about the need for housing, and particularly about Soviet mass housing. I understand that approximately 80 percent of the Ukrainian population lives in Soviet mass housing built since the 1960s, much of which has been severely damaged in the war. How do you deal with that heritage and its reconstruction? What are the attitudes toward it?

Iryna

Perhaps I can start, as a historian involved in heritage preservation. Soviet heritage is a complicated issue that polarizes our society. Before the war, there was a very negative attitude toward the late-Soviet architecture, as it was associated with stagnation, low quality of life, economic crisis, and the collapse of the Soviet Union. But now that these microraions4 have been severely damaged, they are beginning to be perceived as heritage. This broadens the perception of heritage beyond traditional notions of uniqueness or beauty, into an understanding of social value.

Anastasiya

For me, it is quite scary: I cannot see Soviet mass housing as a solution to the humanitarian crisis of displaced populations. Almost 90 percent of that housing stock is now privately owned, and there are no mechanisms for reappropriating it for humanitarian use. We need to find another typology to add to the housing stock, and we need to transform currently vacant spaces. Many millions of people are displaced, and some are considering going back to the Russian-occupied areas because they don’t have support in Ukraine.

Anton

It’s not that we don’t like the housing because it’s Soviet. Many Ukrainian architects and workers built it. Of course, there are concerns about energy efficiency, but most importantly there are issues with spatial order. As almost everywhere else in the world, there are negative aspects of modernist planning from the 1970s and 1980s. In the case of these late-Soviet microraions, planning was very car oriented, and these spaces were unstructured. Sometimes you don’t know where the street starts or ends, or who the spaces belong to.

A monument to the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko is seen next to a destroyed apartment building, Borodyanka, April 2022. Grant Rooney Premium/Alamy.

I often quote Colin Rowe to my students, saying that there are buildings that occupy space, and then there are buildings that define space. People need an understanding of space belonging to them in order to feel responsible for it. We have to resurrect the notion of a European city with structured spaces. It doesn’t mean we must return to a gridded block structure, but we do need clearer spatial organization, which also means a return to compact cities. It’s crucial for the whole country. I think that it’s more important to develop strategies for shrinking cities than for growing cities.

Oleg

There is a crisis of space, which Anton expressed very well, that necessitates a deep transformation. In cities like Zaporizhzhia or Kharkiv, 80 to 90 percent of the population live in late-Soviet housing which, as Anastasiya points out, does not meet contemporary needs. This is the most difficult part of the transformation.

Soviet mass housing, Kyiv, 2018. Alexey Furman/Stringer/Getty Images.

Eve

My second question is about an issue that is central to thinking about the future—whether or not one has to plan for war. After World War II, for instance, people in the US built bomb shelters outside their homes, and there was a movement toward less urban concentration to avoid being a vulnerable target. This was planning for war in many ways. In Ukraine, does one need to plan for war, for defense, or for peace?

Oleg

We have to think about peace, open borders, and an open society. At the same time, we must remember that the threat is ongoing and that we are not in a World War II scenario, with an international coalition fighting against the aggressor. Maybe this will be our reality for decades. We have already transformed our norms. For example, our office is designing a building with a very solid core and a facade that offers maximum protection against attacks. We will always remember these difficult experiences, and we will need to significantly expand underground infrastructure while always thinking about how to use these spaces in peacetime. These protected spaces will be part of our agenda for, I don’t know, the next century.

Anton

Planning for war corresponds with planning for climate change and other emergencies. It involves designing autonomous buildings that are energy-efficient, use local materials, support resilient cities, and incorporate robust energy networks. When the supply chain breaks—as happened at the beginning of the war—you go back to local materials and to simple means of construction. It could be called planning for war, but it is also planning for natural disasters and climate change.

Eve

You make a very good point: one cannot think of wars and climate disasters as being peripheral or even transitional. They are now constitutive parts of global urbanization processes, and we have to think of them as constant conditions that must be considered as we are planning and building. Construction is more and more a continuous process of reconstruction, remediation, repair, and reuse.

Anastasiya

It is paradoxical that we know more about future reconstruction plans than about plans to achieve peace. This has mobilized me as an architect but also made me sad as a human being. We need to act more, test more—without being scared to make mistakes in the absence of a perfect plan.

Oleg

We are shaping new levels of togetherness, and this is a big promise for the future. I strongly believe that this will transform into a new agenda for our social behavior and architecture. But now we need an immediate approach: to resist this aggressor together, to survive in these circumstances. There’s a transformation already underway—reshaping relations between professionals, communities, and inhabitants. Inside expert circles, there is a significant response to these values right now.

Eve

What you’re saying about values is very important, because it is also how we perceive and shape the future. What we value includes the environment, it includes our collective welfare, and in many ways it includes planning for peace.

Oleg

To me it’s also about shaping a new solidarity and a willingness to protect ourselves. That means that the built environment has to provide for solidarity throughout the entire city. It has to be homogeneous, offering a consistency in quality from the city center to its periphery, with shared amenities accessible to everyone.

Will such a city be ready to protect itself? The way we plan architectural projects and new infrastructure is important as a symbolic process of community-building. Maybe this is one of the ways to change ourselves as we change our cities.

Eve

I’d like to add that the idea of protecting the environment and communities—and our sense of social responsibility—is where values come in. We have to protect our communities and our sense of social responsibility because they are vulnerable. This notion of protection as perhaps “caring for” as opposed to “guarding against” is something that I think the experience of war makes us aware of: how vulnerable our environment is, and how vulnerable our social cohesion is. It makes us consider what we do as architects and planners.

Anastasiya

Architects act as protectors in various ways. Those on the front line protect us from the aggressor. One landscape architect told me that he’s still a landscape architect because digging trenches is one of his main duties now, keeping him connected to his projects. Others, like those of us at CO-HATY, plan communities that are more protective, resilient, and inclusive. We try to balance different groups as operators, as providers of housing, and avoid small-scale buildings that will not create a diverse group of inhabitants. We use elements of planning in our community-building processes, and we value inclusivity and integration with the host community. We carefully select the locations of the buildings we refurbish, because this might determine our connection to the neighborhood. We act as planners on a small scale.

Anton

I think you’re right: this war has shown us that we have to create buildings and cities of care. Lviv is a tourist city with millions of visitors. Before the war, Lviv’s motto was “Open to the World.” After the war started, we discussed this with Kees Christiaanse and together came up with the notion of “Habitat of Care.” This is a motto for every Ukrainian city, because the trauma of the war will be present for decades, and we have to be caring, accessible, and inclusive. We also have to ask: What is an architecture of protection? Is it heavy and concrete, visually defensive? Or is it architecture that takes care of people? I think it may be the latter. There are many people with spinal injuries in Lviv. For them, we adjusted and flattened out the Austrian-era cobblestones in the main square to make it accessible for wheelchair users, while preserving our heritage.

Speaking of values, we organized the Lviv Urban Forum three times. In its first year, 2023, the forum was focused on the notion of defining values, because we had to start with values. In the second year, it was about taking responsibility, because if nobody takes responsibility, nothing changes. We organized it again in June 2025. We were very happy to have people like Anne Lacaton, Shigeru Ban, and Alejandro Aravena come to the city and lecture to more than a thousand people, redefining our ideas of how we do things.

Eve

The key here, as you say, is to define values, take responsibility, and think about what it is that you’re protecting while the war is ongoing. When something is under threat, you think differently about what you have, what you value, how to protect it, how to conserve it, and how to foster it. It’s not just a matter of protecting, but of fostering something, allowing it to continue and thrive.

Anastasiya

I cannot stay silent, because this question is brilliant. We should have started with it. Architecture must protect people, during war and beyond. When people consider escaping from cities under siege, they take into account the accessibility of safe accommodation. And when they don’t have access to architecture that is supposed to keep them safe, they stay and put themselves in danger. Architecture should again become a protective instrument, a shelter that offers life-changing possibilities.

Oleg

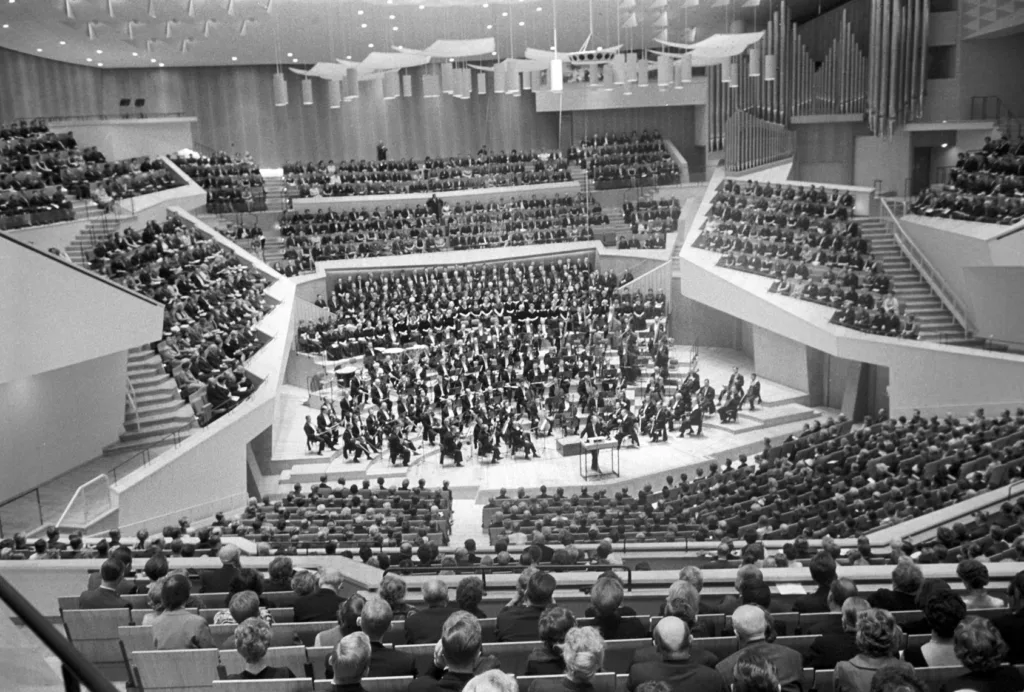

This war is mainly about fighting for certain values, for democracy and peaceful civilization. If we’re talking about protection, I strongly believe that a quality environment can be a defense for a strong democracy. Architecture is very powerful. Part of the force that brought down the Berlin Wall was Hans Scharoun’s Berliner Philharmonie and Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie—good architecture that expresses values, has enormous aesthetic quality, performs well, and hosts powerful events.

The Berliner Philharmonie during the general rehearsal for Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, October 1963. Photo Konrad Giehr/Picture Alliance via Getty Images.

Eve

You make a very interesting point about what architecture can do. Scharoun’s building, in particular, is a statement about society, about coming together; it gives shape to a democratic space.

Oleg

Architecture is very important as a symbolic statement. That is what I wish Kharkiv to be in the future—a kind of West Berlin, demonstrating experimentation and open-mindedness.

Eve

A heartfelt thanks to all of you for taking time for this important conversation.

Blau was the director of the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies from 2022–2025, is codirector of the Harvard Mellon Urban Initiative, and adjunct professor of the history and theory of urban form and design at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

We’d like to extend our gratitude to Igor Ekstajn for his crucial involvement in organizing and editing this roundtable, and to Ryan Locke for his assistance in organizing participants from within Ukraine.