“I Love DPRK”

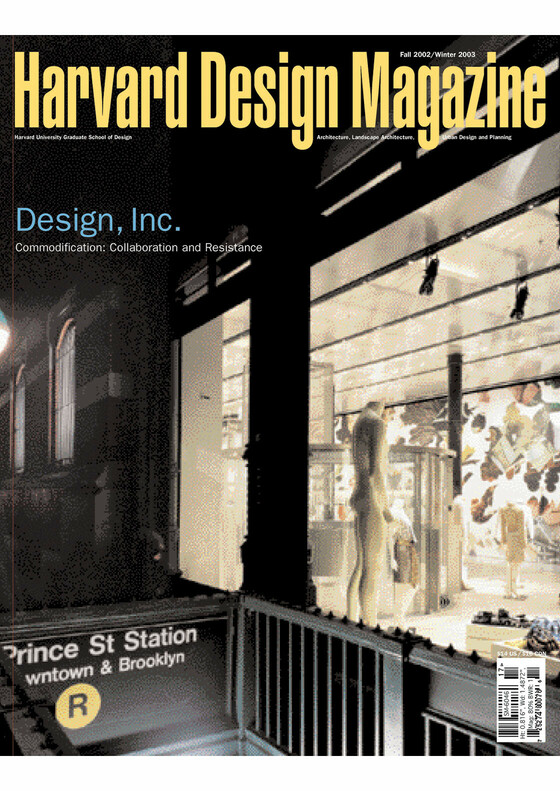

17: Design, Inc. Commodification: Collaboration and Resistance

We have little choice but to adapt to a nasty bind: Work done for some reason other than making money—say, designing a great building—requires money. And making money almost always requires serving someone’s or some organization’s interests. No-strings-attached funding for efforts that surmount the payer’s interests is as rare as MacArthur “genius” grants. Even if, as Rick Poynor writes here, reviving the distinction between instrumental work and work for its own sake is crucial for the integrity of design, in practice the distinction gets blurred.

The topic of this Harvard Design Magazine was developed well before 9/11. Now, in contrast, much of the design community is drawn, with thoughtful and spontaneous concern, to the challenge of transforming the emptiness of the World Trade Center site into something humane and responsive to grief. However, business as usual of course still rules. Those with the purse strings are those with the power. Opportunities for people to work for the common good—in design, publishing, teaching, architecture, urban planning, and landscape architecture, among other fields—have been decimated, even as the need for such work has increased. The world explored and criticized in the feature essays here is a world in which nothing is allowed to or can stand in the way of power’s pursuit of capital. But in the summer of 2002 roadblocks are being built, and it might not be foolish or naive to think that we might be entering a period, like the civil rights era in the early ’60s, when pursuit of the common good increases.

— William S. Saunders (excerpted from the introduction)

Keller Easterling

Kevin Kelley

Michael Sorkin

Wouter Vanstiphout

Rachel Bowlby

Niall Kirkwood

Rick Poynor

Jan Otakar Fischer

Mary Anne Staniszewski

Belgin Turan-Ozkaya

Thomas Frank

Matthew J. Kiefer

Paolo Tombesi

Carl Sapers

Jane Wolff

Bill McKibben

Christopher Long

Brian Ladd

Jill Pearlman