Plumbing the Urban Azimuth (at the End of the Age of the Book)

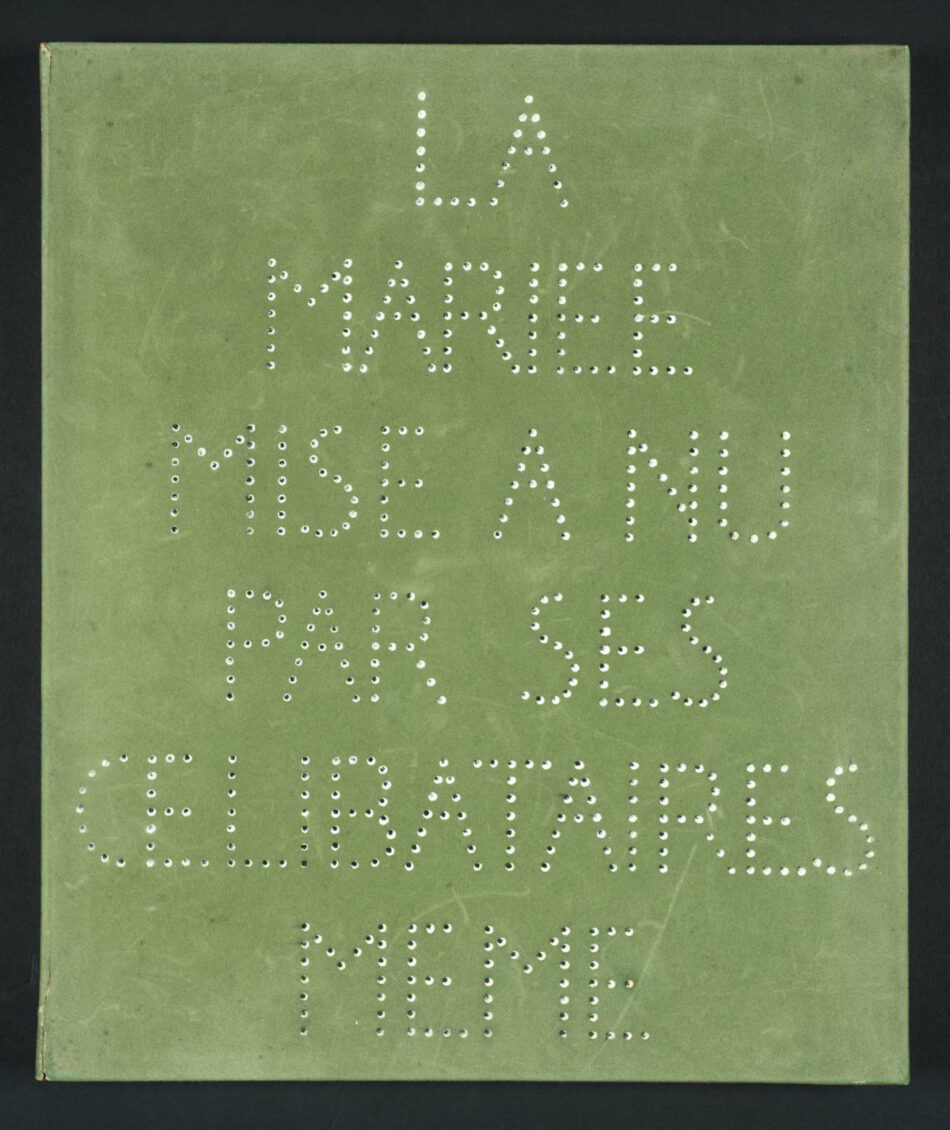

My passage as a student from Paris to New York City in the late 1970s was imagined initially as a labor of transposition (reconciliation) of cultures of a European philosophical avant-garde with an equally powerful, but as yet untheorized artistic one in America. The passage, however, unfolded psychically as a collision and consolidation of histories with eerily parallel roots in earlier, clearly more legendary migrations, including one that always carried great significance for me, that of Marcel Duchamp.1 Duchamp’s curious zigzag migration in the early 20th century forged a seamless unity between old-and new-world modernities, a phenomenon that had been incompletely grasped before the 1980s.2 Duchamp’s inalienable centrality to the most important American aesthetic developments of the pre- and postwar eras was of the order of a Trojan horse that breached any prevailing distinctions between traditions or divisions of disciplines. His fully cosmological-epistemological art project changed what it meant to think and to execute work in the cultural sphere by removing the ramparts that separated art practice from the broader matrixes of cultural and historical meaning, particularly of language practice.3

No surprise then that among the questions that pressed on urban intellectuals in the 1980s was, “What does it mean to claim to know something in the current world?” A spectrum of ethical and political concerns was thereby invoked—preeminently, the question of how the modalities of knowledge were palpably and fundamentally changing, as well as certain wider problems that pertained to historical change itself, to the need to identify causal forces and rigorously distinguish them from consequent ones (and to avoid the historicist platitudes that routinely accounted for these). The relations between history, form, and knowledge were being recast in these years; indeed, they were set into philosophical perspective as a single problem for the first time.4

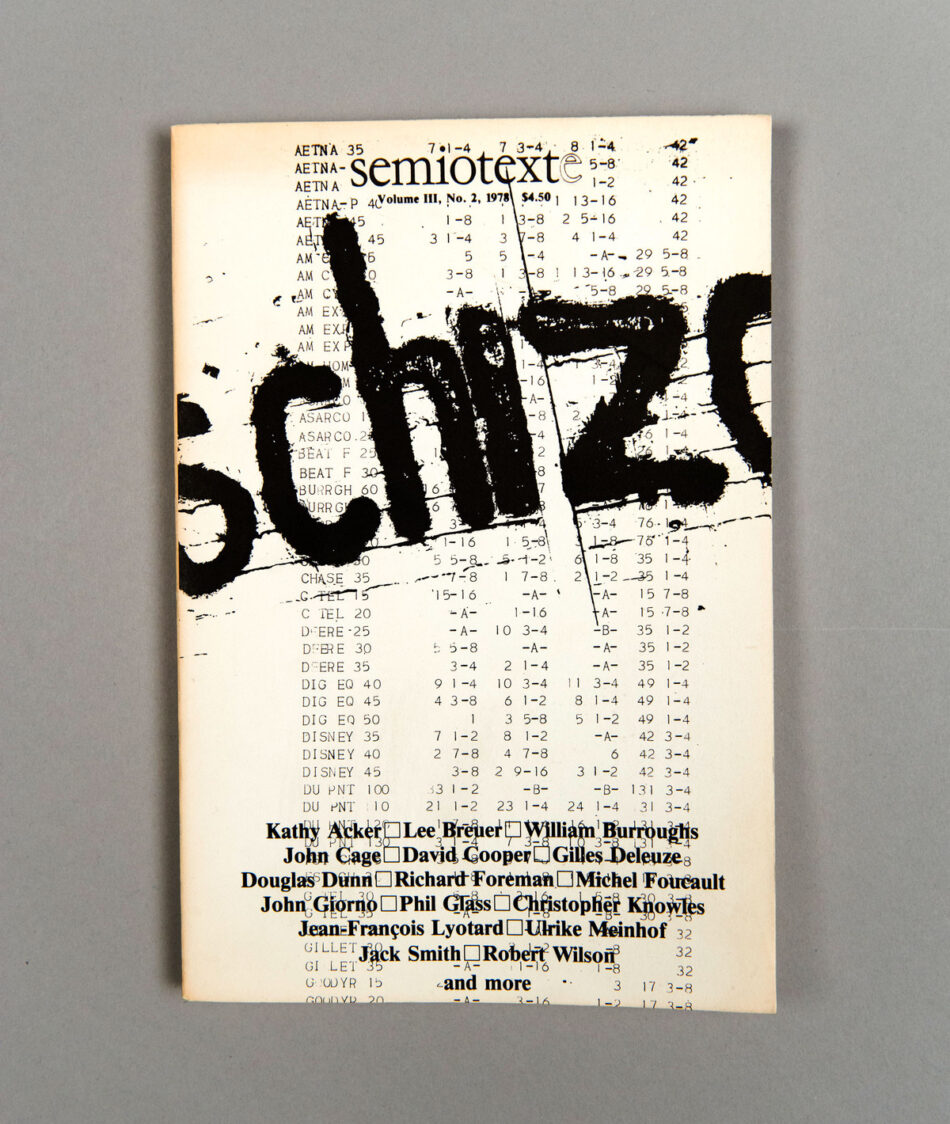

The two enterprises—one neo-structuralist (October), the other Nietzschean post-Freudo-Marxist (Semiotext(e))—remained largely culturally distinct within the New York context. The former was based at New York University and Hunter College, the latter at Columbia, but the city itself, with its enormously confident artistic and literary endowment of radical practices provided an anarchic and fertile seedbed for miscegenation that needed only to be dreamed up in order to be set into motion. To the degree that this historically rooted confrontation served as the rearing environment for a young generation of cultural practitioners, an unrecognizable but consistent worldview was arguably being shaped that was accessible—because it was at once necessary and natural—only to the generation to follow.

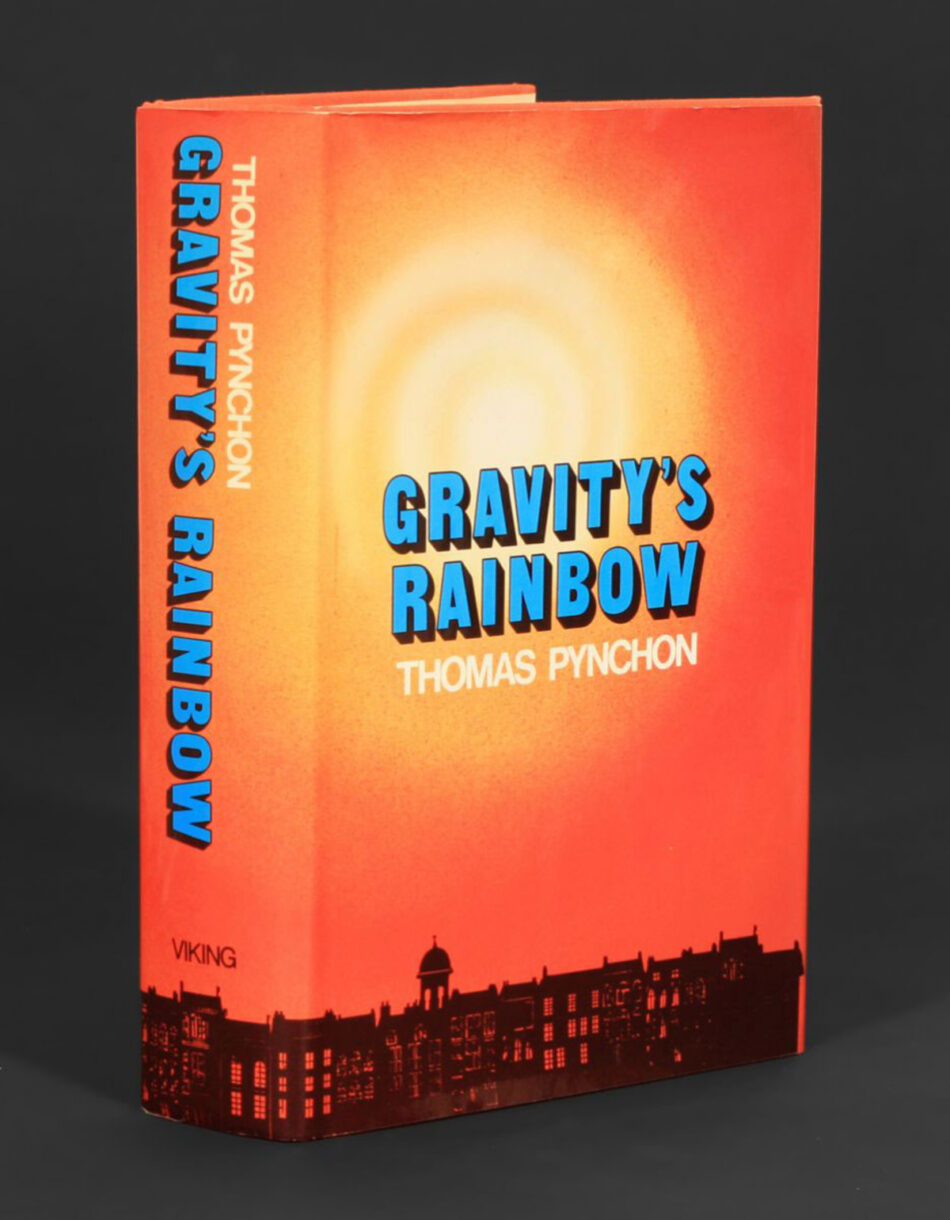

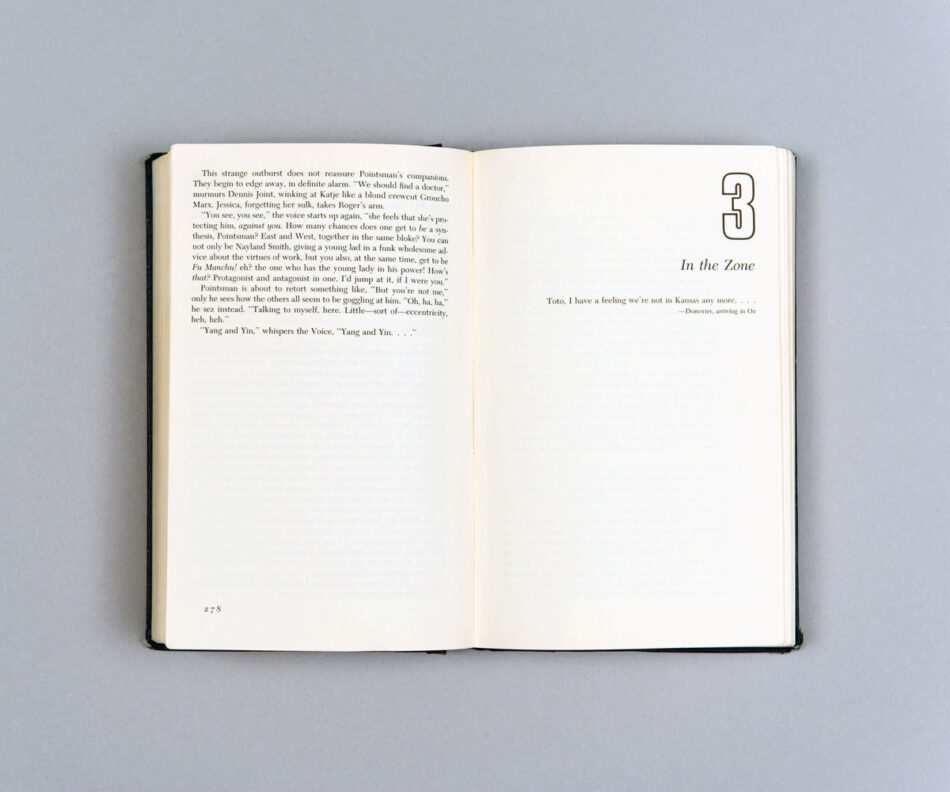

There is no doubt that Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow and Smithson’s Spiral Jetty—short forms for an emerging expansive model of practice of almost unprecedented scope and cosmopolitanism (pace Duchamp and James Joyce) that breached every possible boundary of disciplinary integrity—provided central inspiration and entirely unexplored surfaces for the engagement of history by thought and vice versa.8 The novel of the 19th century represented the art form par excellence of the urban-social realm, the purest expression of capitalist forces on both public space and interior subjectivity. Hence, the dual articulation of city and mind by modernizing forces9 could easily be called on to provide a basis for privileging “the book” as the site of both political intelligibility and struggle in the modern era.10 Pynchon’s own reworking of the spatiotemporal matrix of novelistic narrative as a pattern of technological, scientific, and economic forces that comprise a new type of “city” (hence “the zone” of Part 3, and the pervasive evocation of the parabola as both a statistical distributional principle—the Poisson equation—and as a trajectory) staked its claim at once to being the last great novel in a 200-year-long tradition and the harbinger of a new type of literature to come.

If the classical novel gave expression to the modern (capitalist, bourgeois) experience of time and space—three-dimensional, multilayered, cumulative, yet perspectivally rendered and hence “fraught” with forces in occlusion or background—Pynchon’s space-time manifold recast the historical world in the decidedly contemporary syntaxes of the uncertainty principle, statistical mechanics, and psychosis. There is a remote logic by which the world is organized, but it is no longer the stable or empirically graspable one based on familiar optical principles. Reading would forever require the deployment of concepts, competences, models, and methods of a different order.11

ZONE 1|2

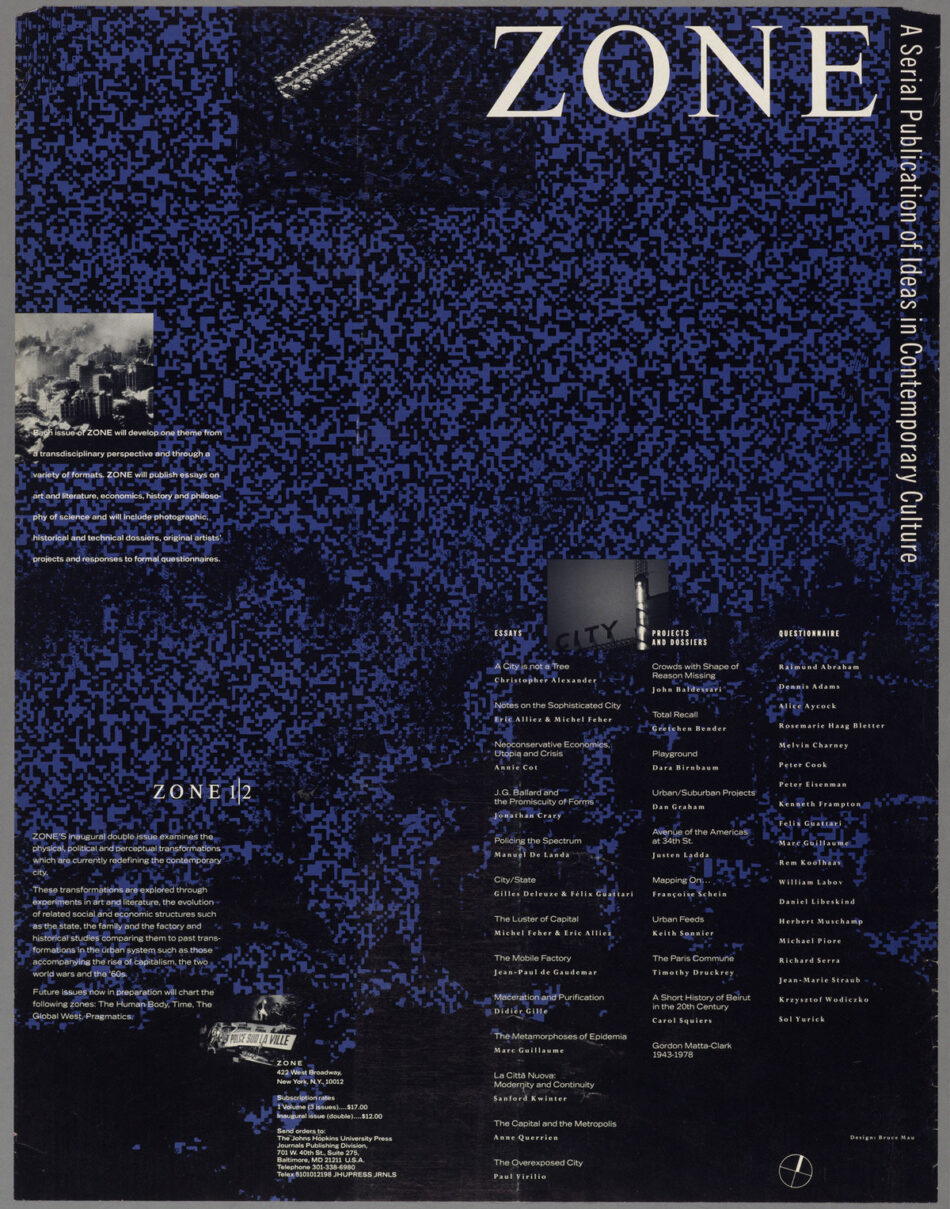

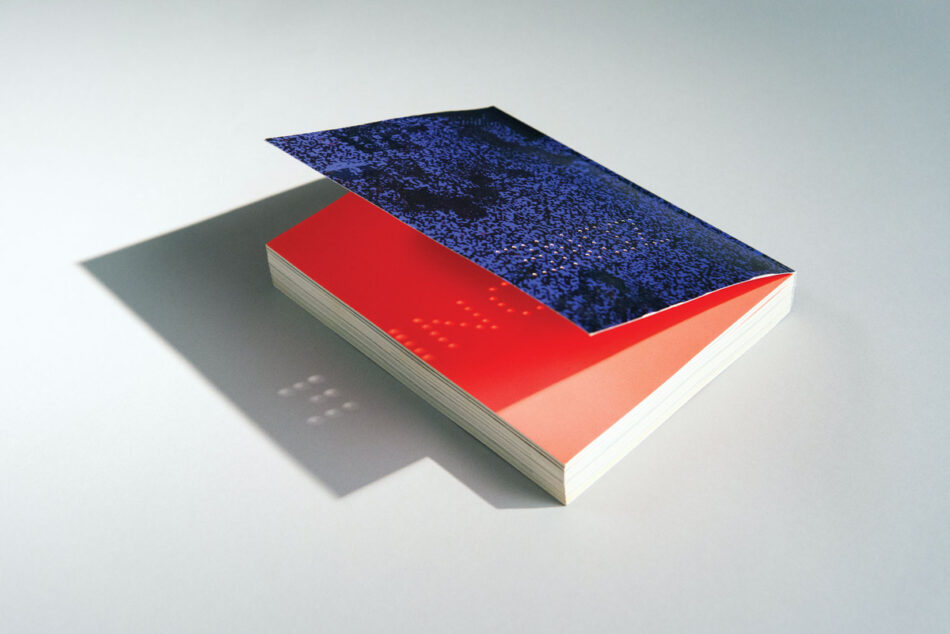

The preceding account represents a small part of the local context within which the publishing enterprise that found its first product in ZONE 1|2: The Contemporary City was conceived. From its initial conception in late 1983, any complacency with respects to the role and status of a “journal” in the tradition of Critique, New Left Review, Les Temps Modernes, and the like, was already all but ruled out. The first waves of what would become a comprehensive transformation of our media sensorium were being set into motion, granting undeniable privilege to the expressive generality of the image at the expense of text. Proclamations regarding the imminent “death of the book” were neither rare nor solely the products of illiterate media industry apologists, but belonged to an increasingly giddy cultural class confronted by new representational possibilities and attendant modes of attention whose deeper consequences could only dimly be imagined at the time. Our task with ZONE 1|2 was foremost to affirm “the book” in the face of an increasingly systematic assault on traditional literary experience by the emerging forms of automatic, mechanically reproducible, and mass-distributed imagery of all kinds—a kind of psycho-ecological project of activism and engagement.

Literary critical dogma (particularly French) often in those days methodologically privileged the so-called incipit of a text—the initial words, phrases, or even paragraphs of a manuscript that comprise and condition the reader’s entry into the text’s “matter”—which led to the placing of particular emphasis on the conceptualization of the book’s cover.12 Research on the history of bookmaking with Bruce Mau (who had yet to design a book) brought the surprising clarification that a book’s cover (or to be precise, its jacket) belonged traditionally not to the book itself but rather to the retail or public environment in which a book is deployed and displayed, in which it claims its place among other books, and in relation to the public eye and mind of the citizen-reader. The cover was therefore conceived as a material part of the extended urban infrastructure within which it was intended to operate, was devised to serve as a communicative but also commutative and conductive surface. At any rate, it was no longer a mere passive carrier of semiotic figures or signs as had come to be the case in the commercial environment generally.13

An early example of intellectual effort that both studied and enacted this emerging “manifold” concept of history, and arguably descended directly from it, was Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe and John Johnston’s prescient (if largely impenetrable) three-part semiotic study of Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 Gravity’s Rainbow and Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) that appeared in the inaugural three issues of the new revisionist journal of aesthetics October.5 If this essay-experiment produced but a modest illumination of its objects and method, the audacious and unmistakable performance of the common matrix that arguably alone could render these two landmark works intelligible (the principle of entropy, for example, and the shift in worldview it required), was itself an event of cultural and epistemological significance. During these same years (and in essence in the same place), the publication program of Semiotext(e), led by Sylvère Lotringer,6 and its sponsorship of occasions such as the “Schizo-Culture” conference at Columbia’s Teacher’s College in 1975,7 had a near-militant purpose: the de-academicizing, de-ghettoizing, and de-segregating of thought and cultural practice at a time when two radical cultures (New York/America and Paris/Europe) remained separated like two chemical compounds whose volatility—but also whose capacity for mutual illumination and heightened expression—would multiply exponentially only once combined.

The refusal to include signifying language (and linguistic signs in general) anywhere on the cover of our publication may have represented a type of risk, but it was powerfully motivated by a set of factors saliently active in the perceptual-psychic environment of the time that arguably accentuated, rather than diminished, the book’s physical presence and “power to affect.”14 Although the design and assembly process of ZONE 1|2 was executed entirely with Xerox machines and the panoply of hacking techniques that were then all but routine among innovative designers, the publication was conceptualized throughout its three-year inception within the powerful shadow cast by the Macintosh desktop computer and the novel under-the-hood ethos and routines that its operating system and font management software fostered. Pixels had made their existence felt in a profound and game-changing way initially within the visual sphere—apprehensible, manipulable, and modifiable molecular or atomic elements that were increasingly seen to subtend the formation of concrete entities in the perceptual and lived sphere. In many ways, the emerging notions of “information” were seen to offer alternative concepts and heuristic approaches to the analysis of history other than the still pervasive theory of “signs” in academic and cultural milieus. If theories of information could now claim to replace those of signs, concepts such as those of interface, protocols, thresholds, and planes of consistency came to the fore.15 These brought with them a broader transformative conception of transmissional principles, based not in the immaterial (transcendent) values of signification, but on the conductive (and immanent) properties of matter.16 Hence the mottled but mysterious surface of the book presents an infinitely extendable surface of legibly varying density such as in the raw, unfiltered data of a (1980s) satellite photograph. The densities of ink were generated by embedding a panoply of bird’s-eye-view images of city matter and urban objects with objects of different (smaller) scales at once across but more pointedly within the blue pixelated landscape. In doing so, we sought to assert the physical univocity of the relationships within the emerging contemporary urban regime. The menacing impenetrability of the surface—bordering as close to indecipherability as was possible within the norms of visual culture at the time—was in no small part borrowed from the rendition of the cryptic façade of the Tyrell Corporation in the groundbreaking “all-over” art direction of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), which was dominating the popular visual imagination at the time.17

The rendition of the Tyrell Corporation building unambiguously tapped into the paranoid-static mood of microchip aesthetics then beginning to gallop through the cultural imagination.18 The advent of the microprocessor in consumer electronics induced a set of effects that were seismic in impact given the way they stored, remembered, and read out history and time within an engineered opacity that was not merely a question of scale, but also of configuration; and these functions and behaviors were directly carried over from the dynamics of “the book.” Hence the purpose of the ZONE 1|2 cover was principally to dramatize the expanding gap between reality and the forces that determine it, and to declare an emerging crisis of legibility that was already beginning to mark our civilization as a historical singularity on a vast scale that demanded a proper accounting.19 Hence, not only were linguistic signs put out of play as remnants of an outdated mode of thought and a no-longer hegemonic avenue of social production, but matter itself in its curiously eloquent muteness was affirmed as a “productive and expressive” continuum that would by necessity absorb the image into its logic, not the other way around.20 The deliberately unspeaking cover sought to operate as a kind of point-of-purchase black hole that would create a signifying void amid the bookshop arrays, a bibliological dark matter to stand out against the typographic monotony of lurid colors and default fonts that made up the then (predigital) publishing environment within which book covers were conceived as crude advertisement panels for themselves.21 The refusal of the image was a point to be made amid this generally tawdry context but it was also intended to serve as a striking counterpoint within the design system of the book itself, which represented one of the most image-intensive intellectual book projects in perhaps two decades. Only the obscure word mark “Z O N E” appeared on the book’s exterior, but as a subtraction not an addition, rendered by a stamp perforation that penetrated through the palimpsest of the cover to reveal a system of actual, not representational, materials and substrata below.22

ZONE 1|2: The Contemporary City was conceived to operate not as a composition that referred to, or represented, the city beyond, but as a system of matter and force that would operate, whenever and however possible, in unbroken continuity with, and as consubstantial to, the extended city itself. For this reason alone its task was to take on, and in so doing palpably to deploy, the compositional forces that were engendering contemporary urban experience at large, and to push their ambiguities to the threshold of expression.

How one reads a city, or “the” city, in its historical unfolding of interconnected and transitive generality, may not be distinguishable from the problem of reading per se. “The book” and “the city” have throughout modernity been indivisibly conjoined environments or continua23—the one engendering, and by turns subtending, the other in a mutual evolution in which the habits of mind that enable the deciphering of spatial relations and the modes of inhabitation at a particular historical moment are effectively secured.24 It is not what a book represents that belies this relationship (as in the principles and traditions of realism) but the forces and configurations of which it is composed. The novel, for example, corresponds broadly to the early industrial formations of capital accumulation and organization, partly because of the way it deploys and organizes space and light—and hence both knowledge and knowability—and partly by the way that it configures the subject through the constitution of character and its “fraughtness” with social and environmental relations. The creative crises that emerged in literary representation in both novelistic and literary space and in the modes of animating protagonist subjects in so-called modernist literature and beyond (say from James Joyce and Franz Kafka through Céline to Pynchon) transformed human subjectivity just as they responded to transformations in the conditions of legibility unfolding in the ambient historical world. Yet literature does not subsume all books, even if all books perforce participate in the same system of constitutive relations as literature. It was one of the capital insights of the 1970s and 1980s philosophies—in no small manner related to earlier developments in the plastic arts—that “the material of which something is made is inseparable from the processes it performs,”25 or more simply, that what used to be thought independently as form and content are in fact inextricably and performatively one.26 How a book is made is inseparable from what it does, and the hyperinvestment of its material and structural qualities—its ordinality, syntax, conjunctive and disjunctive musicality, even its psychotropic capacity—was seen as a full-blown urbanist practice itself, akin to a time-based dérive, to scientific cartography, or to social cinema.

The dominant epistemological trope of the 1980s was indisputably the idea of the map as a model or way of knowing the fugitive properties of historical becoming through configurations of space. Be it in the work of Smithson, Pynchon, J. G. Ballard, Borges, Foucault, or Duchamp before them, the practice of topologizing relations of force was preeminently a way of grasping and depicting the adventures of both their interactions and transformations. The favored idea of the map at this time was less the microcosmic reflection of a next order scale of reality, but of a polyvalent and multidimensional surface that was coextensive with the mapped reality itself, and which was capable of isolating relations from the otherwise infinite and incompletely knowable opacity of the world.27 A map was in this conception an “intensive manifold,”28 enterable at any point, capable of being used improvisatorially to plot routes or connections from any point or place to any other, as a performance of reality rather than as a mirror or picture of it. The texture of the flow of ZONE 1|2, the patterning of events, was conceived within this framework as an interleaved matrix or a polyphony of correlated durations that could be deployed as a volume rather than a line, as an environment rather than determined sequence, and into which further modules could be indefinitely inserted as historical conditions both within and without the book began to change.29 The book’s envelope was seen to serve as a site at once of attachment and conjunction with extensive realities in its historical surround and a compression and deceleration (slowing) of the movements revealed within its boundaries. The book in the 1980s was still a privileged site of encounter with power relations and the formations of subjectivity, just as today attentional demands—and power relations—have migrated significantly to modes of interaction and participation, particularly within data environments in which everything is dynamic rather than fixed, and where what produces difference and value is what occurs rather than what endures. Regardless of how accurately this account might seem to represent the current state of things, we must not be duped into imagining that we are somehow living history outside of material conditions or their jurisdictions.30 Print (ceci) never killed the cathedral (cela), but rather could be said to have discovered in it an opacity proper to itself that it never knew it had. And this endowed each with a transformative power that could ever after only be shared, as would be their coupled fate, as urgent, precarious, and perhaps doomed as is freedom in our emerging cities itself.

What were these forces? The extensive domains that we (perhaps primitively) refer to as “cities” have always been the result of abstraction processes, processes originally performed materially in an extended reality then rationalized or routinized. This means, more often than not, that they are transformed into numbers so that they can be made to operate independently of three-dimensional constraints, and hence outside the jurisdictions of matter. Abstraction permits concentration, acceleration, and displacement of material, social, and economic processes, all while maintaining, or extending by other means, their effects. The urban realm in these years—the city in the 1980s was very different than the one we know today—was undergoing a series of reorganizations of profound local impact driven by technological developments particularly within the electromagnetic spectrum: the multiple expansions of cinema seen in the explosions in video practices and technologies; the impact of the first time-storage microprocessors in consumer electronics (answering machines, VCRs); automatic and round-the-clock banking transactions and infrastructure (ATMs to the daisy-chaining of international stock exchange schedules); telecommunications; desktop and industrial computing; exchangeable files; image processing; archiving; networking and social circulation protocols of all types. All this not to mention the attendant transformations in power relations that were part of broader modernization forces based in the mass infrastructures of signal processing, which had not yet consolidated into the almost single manifold they are forming today. Not only was it a problem for thought to engage these developments in the medium in which they were being played out, it was a problem for design as thought to deploy itself in direct connection to, and in propinquity with, the effects themselves.

remained overwhelmingly innocent of the transformations in awareness that accompanied the economic and cultural globalization of the 1980s. The alembic of cultural ideas was still comprised of European and New World reagents uniquely. Symptomatic was the unqualified and widely parroted use of the terms “the West” and “Western” in the work of Jacques Derrida (and countless others)

throughout the 1970s as near-cover terms for human historical experience. 4 I refer here to a strand of thought that was shaping understanding in those years, whose lineage stretched from Friedrich Nietzsche through Alexandre Kojève and Georges Bataille, to Michel Foucault and Deleuze, and which powerfully impacted correlative developments such as the more critically-oriented projects of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Derrida, and extended as far afield as to that of Jean Baudrillard. 5 Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe and John Johnston, “Gravity’s Rainbow and the Spiral Jetty,” October

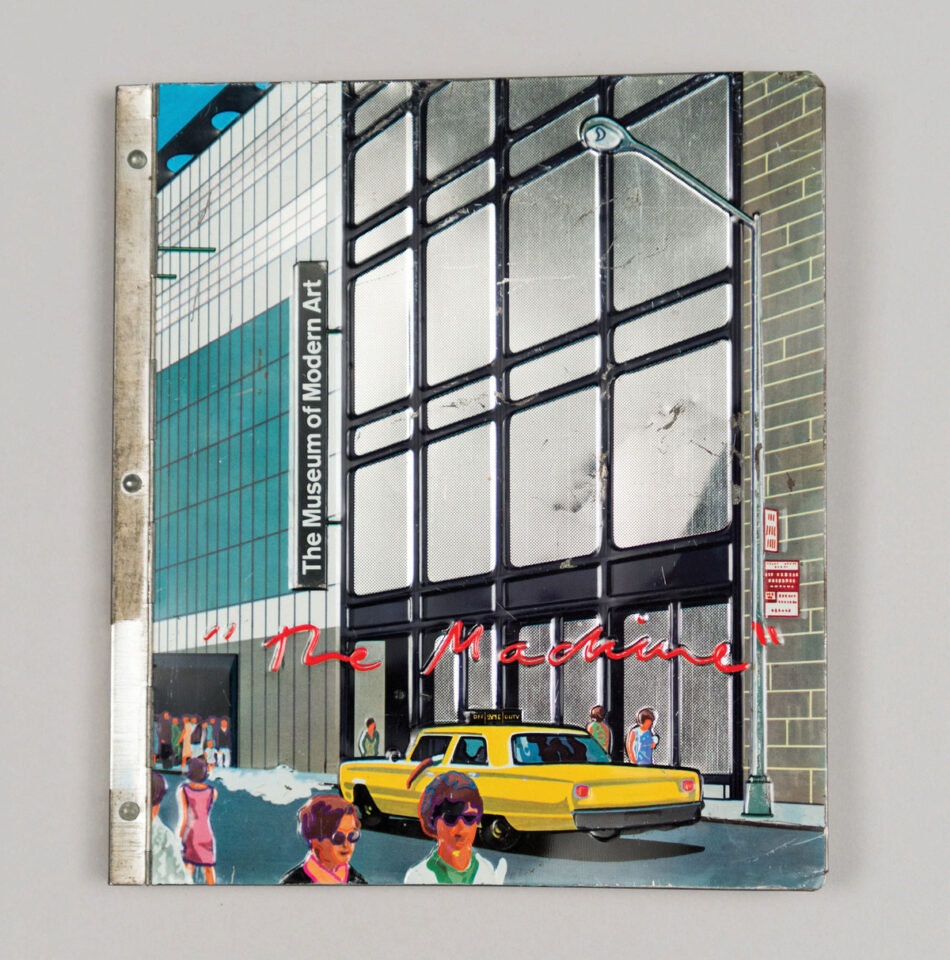

1 (Spring 1976): 65–85; October 2 (Summer 1976): 71–90; October 3 (Spring 1977): 90–101. The journal was founded and edited by Gilbert-Rolfe, Krauss, and Annette Michelson. Gilbert-Rolfe and Johnston’s was the first (and for a long time, the most) serious and intellectually ambitious treatment of Smithson’s work. Cf. also Craig Owens’s “Earthwords,” October 10 (1979) for the “postmodernist” reading of Smithson’s work (“allegorical,” “decentered,” etc.) that became the October position consequent with the early departure of Gilbert-Rolfe from the editorial board. 6 Lotringer taught in the Department of French and Romance Philology and Johnston was a doctoral

candidate in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. 7 See François Dosse’s account “Winning Over the West,” chap. 26 in Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari: Intersecting Lives, trans. Deborah Glassman (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010). 8 The opening sentence of Gravity’s Rainbow—“A screaming comes across the sky…”—and its first

depiction of the copula arc that conjoined (rather than separated) the “evil” forces of the continent (the V2 rocket paths and the systems of rationality that subtend them) with the knowledge systems of the Anglo-Allied forces (cryptography a la Alan Turing would be but one emblematic example) was taken

as an affirmation of the archaeological necessity (intended here in the fully Foucaldian sense) of a transcontinental publishing project with respect to the emerging cultural forces and postwar knowledge systems. 9 This dual articulation formed a foundational principle of German sociology from Max Weber to Georg Simmel and Siegfried Kracauer. 10 From today’s perspective, it is difficult to imagine the degree to which urban existence in the pre-digital, pre-globalist era could have included such an intense and direct experience of historical forces on an almost quotidian basis. It is also all but unimaginable today how the cultural preoccupations of a locally circumscribed civilization could have provided such a constitutive backdrop and foundation through which to filter and focus that experience. Just as to live in postwar Paris was inescapably to engage Sartrean political existentialism in all its concrete forms (in cinema, literature, and music, as well as in everyday relations in the public arena—in cafés, the workplace, the bedroom, the universities and, by 1968, the streets), so in New York City it was impossible not to engage the dreams of transformative experience, from the political to the psychedelic, through its art practice and associated ecologies (which in no small measure included aesthetic theory). Cities in the developed world were still privileged sites of historical practice, for they continued to sustain a pre-fragmented intellectual class within and alongside that of the ruling and moneyed elites, assuring a continuous, explicit expression of lived contradictions in both empirical and theoretical forms. In sum, it was impossible in the years after World War II to operate as an intellectual other than as an urban one, and impossible in New York to bypass art practice as a privileged domain for the shaping and control of political subjectivity. Clement Greenberg’s essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” could easily serve as fulcrum for this argument. See Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Partisan Review 6, no. 5: 34–49. 11 The work of Smithson, treated through the single exemplar of Spiral Jetty in the Gilbert-Rolfe/Johnston essay, broke ground far more systematically than by the parochial and routinely noted deployment of language and photographic representation within a sculptural enterprise (Owens,

“Earthwords”), in ways that touched profoundly not only on narrative and text, but on cinema and geology, nature and knowledge, mind and matter, time and space, order and disorder (paradox, dissymmetry, gradients, eclipse), and so on. Smithson’s formulation of “site and non-site” oscillations and reciprocations—at once disjunctive and conjunctive in their operations—provided an entirely new level of possibilities and potentials for anyone embarked on an enterprise of “making sense” or producing meaning in the cultural sphere. The concept of “what a book could do” would, to say the least, thereafter require substantial rethinking. 12 The incipit dates from the manuscripts of the Middle Ages and its use carried on long after the age of mechanized printing, indeed throughout the period before books came to bear formal titles, a

surprisingly recent development which carries its own set of conventions, protocols, assumptions, moods, and affectations, so omnipresent and routine today as to escape notice, but so odd and artificial when brought to one’s attention as to appear an almost alien codification, as abstract and complex as

any stylistic tradition or form we have. 13 Among ZONE’s guiding principles was a neo-pragmatic—and hence anti-semiotic—approach to

thought and its objects of study along lines outlined in the then not-yet-published translation of Deleuze and Guattari’s Mille Plateaux (A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi [Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987]). See Michel Feher and Sanford Kwinter, foreword to ZONE 1|2: The Contemporary City (1986). In the mid-1980s it was said that the average urban dweller encountered, and recognized, 13,000 logos in a single day. 14 The phrase, borrowed from Spinoza by way of Deleuze, describes a world made uniquely of “kinetically” composed bodies that enter into “dynamic” relations expressed through a spectrum of interacting “modes”—“arrangements of motions” that modify or enter into composition with one another. See Gilles Deleuze, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, trans. Robert Hurley (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1988), 123–26; and Feher and Kwinter, foreword, 10–13. 15 The term “zone” was a response to a set of philosophical, methodological, and political concerns. The topos of the broader intellectual project (of which “the city” was but one of three initially projected topics for treatment—the others were “time” and “pragmatics as a method of inquiry”) was to map the changing structure and modalities of contemporary knowledge. It corresponded to the “correlative space” in Foucault, the continuum that puts an enunciative statement into relation with its subject,

its object, and its concept—in sum, its concrete relational space of deployment. It followed the principle that one does not study objects, but rather the fields in which they operate and the topology of their operations. In this sense it internalized the presupposition of a landscape of forces—complex and fluid—whose relations and configurations can be mapped in flagrante delicto as it were, on the fly. But “la zone” (as in Apollinaire’s poem, or Pynchon’s postwar deterritorialized and remapped Berlin) denoted the areas at the edges of formal settlement protocols—edges of a city in standard usage—where the

classical and legible structure breaks apart, where wild, volatile, and especially unforeseeable events take place. A zone was equally a space of recombination and innovation where counterforces reside; an origination point of what is not, and cannot be, anticipated. 16 A “plane of consistency” or a “plane of immanence” was a central concept of Deleuzian ontology that had already started to mark thought in the 1980s. It posited a plane or surface of aggravated non-Euclidean relationships of force that provided infinite possible encounters and admixtures of material, social, and psychic substance. It is the “space” where all “composition” of real entities takes place, where any object can be related to, or find operational connection with, any other. It is always ultimately a social space, even when intensely private. Another philosophical work in this early period that provided a few important armatures for thinking the emergence of a digital/analog divide was Anthony Wilden’s System and Structure: Essays in Communication and Exchange (New York: Tavistock, 1972). Of central importance, too, was John Austin’s How to Do Thing with Words, in which he brought the concepts of illocutionary and perlocutionary acts first to a French and then to an Anglo-American audience. These terms gave place to a counter-signifying philosophy of “ordinary” language (following the philosophical redirection of the late Wittgenstein) in which “speech acts”—such as the act of yelling “fire!” in a crowded room—produce undeniable and essential acts of transforming states of reality (such as emptying the building). This came to be associated with a postwar “pragmatism”

that served as a basis for thinking language practice in direct relationship to physical reality and changes of state. See J. L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962), and

“Performatif-Constatif,” in La philosophie analytique (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 1962), 271–304. These ideas played a principal, even if cryptic, role during Foucault’s methodological years in the turbulent aftermath of The Order of Things (1966). See Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, trans. A. M. Sheridon Smith (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972 [1969]), and L’ordre du discours (Paris: Gallimard, 1971). 17 The term “all-over” was coined by Clement Greenberg in the late 1940s to denote a treatment of the canvas surface when filled from edge to edge with paint and so as to “freight” every square inch of

the painting equally with subject matter or painterly incidents. The work of Jackson Pollock is typically given as exemplary of the all-over technique but the tendency to reduce hierarchy and to invest the entire painting surface equivalently was a common tendency in midcentury abstraction. The saturation of the frame in Scott’s filmic art direction was an extraordinary (and successful) experiment in filmic mise-en-scène and was beautifully adequate to the closed and fraught natural world of post-eco-disaster earth and especially poignant in its ability to invoke a metaphysical universe without possible transcendence. 18 Cara McCarty’s exhibition “Information Art: Diagramming Microchips” (1990) at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, sought to naturalize the more menacing aspects of solid state operations by likening their global design to tapestry pattern, textiles, tartans, and post-painterly geometric abstraction. 19 The American film noir of the 1940s and 1950s played a central role in the development of both the themes and the art direction of ZONE 1|2. Of particular note here was the systematic use of lighting techniques borrowed from German expressionist cinema, which in the noir idiom endlessly favored night shots, obscure diagonals, murkiness both visual and moral, vertigo, and anomie. The city is almost always the backdrop in noir, but it is an essentially obscure, menacing, unknowable, and destabilizing force that ultimately is not graspable by the male protagonist and is more often than not associated with the fulcrum figure of the femme fatale whose capacity to set the world into bewildering and frantic motion ultimately leads to the protagonist’s demise. Blade Runner is a deliberate and pure example of the genre in which the city’s legibility remains always beyond the character’s grasp. 20 This was clearly not the case within the ranks of the October group discussed earlier, who continued to resuscitate semiotic sensibility by wedding it to Benjaminian concepts and neo-productivist theories of image-making and circulation. The dubious but highly successful use of the

term “postmodernist” was a direct outcome of the October group’s unwillingness to address the ontological transformations within which the symptoms they were analyzing emerged. In many

ways this may be seen as a symptom of the disciplinary segregation and of the generally Anglo-Saxon context in which the “continental” ideas were being only partially absorbed within aesthetics at the time, and hence the adherence to the practice of “theory” distinct from the more foundational philosophies that in no small way drove it. ZONE was not a journal of aesthetics and maintained a militant adherence to transdisciplinarity. October, self-consciously styled on the purist French model of the cahier and the dry, no-nonsense ethos of the communist pamphlet, exhibited a strict abhorrence of imagery in its pages, but perhaps also implicitly of the risks of intellectual speculation outside the boundaries of central committee doctrine. Regular editorial gatherings engaged potential contributors in ideological catechism to confirm credentials as a precondition of appearing in its pages (approved

allegiances included Lacanian, structuralist, Adornoian, etc.). By contrast, the initial publication of ZONE elicited the derisive description from one English reviewer as the product of “high-spending,

Nietzschean, francophile aesthetes,” bearing witness no doubt, to, among other things, the project’s roots in the post-revolutionary Reichian ethos at once of the anti-psychiatry movements and the anti-“repressive desublimation” philosophy of Herbert Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization, and in the Foucauldian injunction against the fascisizing bureaucratization of the revolutionary posture that had been widely taken up by Semiotext(e). See Herbert Marcuse, Eros and Civilization (Boston: Beacon Press, 1955); and Foucault’s preface to the English translation of Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (New York: Viking, 1977). 21 I have discussed this effect elsewhere as a “salience of absence.” See Sanford Kwinter, “A Note on the Type,” in Requiem: For the City at the End of the Millennium (Barcelona: Actar, 2010), 111. 22 The peek-through heat of the Schiaparelli (or “shocking”) pink from the first inside spread as it bleeds through the pinholes of the die-cut “Z O N E” was devised to transmit light primordially, a kind of jour or daylight that relieves the noiresque claustrophobia, compression, and anomie posited by the cover. The penetrative axes of the die cuts signal transections and transversals that connect the cover’s plane of immanence, like a prominent urban boulevard, to the various materialities within and beneath. In all, it signals the existence of a living entity—the city—that can scarcely be contained by the forces that seek to control it. 23 See Ian Watt, The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1957); and Erich Auerbach, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1953), particularly chaps. 1, 11, 12, 18, 19, and 20. 24 It was a central ambition of ZONE 1|2 to free urbanist thought from the disciplinary quagmire in which the urban was conceived as a merely larger-scale architectural (mechanical, formal-spatial) problem or domain of inquiry, and to reattach “city” to the same lineage of modernizing forces that gave birth to it in the first place. 25 “The material itself must be part of the creative act.” Karlheinz Stockhausen in Karlheinz Stockhausen and Jonathan Cott, Conversations with the Composer (London: Pan Books, 1974), 36. 26 Louis Hjelmslev developed the semiological models of the Prague School and of Ferdinand de Saussure in the alternative direction of the materiality of communicative systems. He famously reorganized the Sign into a form of content and a form of expression, a substance of content and a

substance of expression and refocused analysis on the form-substance axis and hence on the material determinations of communicative practice. Here, Hjelmslev’s work can also be said to have provided much of the basis for the post-structuralist pragmatisms that followed 1968, particularly in the work of

Deleuze and Guattari. See Louis Hjelmslev, Prolegomena to a Theory of Language, trans. Francis J. Whitfield (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969), 47–60. 27 Beyond the familiar disciplinary commonplaces regarding “cognitive maps” (from Edward C. Tolman’s rat and maze experiments), the switch in reference and spirit at this time included Lewis Carroll’s “non-sense” logical speculations in “Sylvie and Bruno Concluded” (the 1:1 map) in The Complete Illustrated Works of Lewis Carroll (Herfordshire: Wordsworth Library Editions, 2008), 11; Jorge Luis Borges, “On Exactitude in Science,” in Collected Fictions, trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: Penguin Books, 1998), 325; and preeminently, Gilles Deleuze’s essay on Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, “Ecrivain non: Un nouveau cartographe,” Critique, no. 343 (December 1975): 1207–27. All of these works were speculations on the modern problem of knowing and reading. 28 See T. E. Hulme, “The Philosophy of Intensive Manifolds,” in Speculations: Essays on Humanism and the Philosophy of Art (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1936). Hulme was a poet and critic of substantial influence on many of the great English modernists, particularly T. S. Eliot, but his singularity of thought placed him far outside these traditions. The essay in question is a study of the

philosophy of Henri Bergson, for whom he worked, and whence came the conception of intensive vs. extensive multiplicities. Hulme’s remarkable cosmological/epistemological essay “Cinders” from the same volume posits the joint problem of matter and knowing: “The world is a plurality. […] This plurality consists in the nature of an ash-heap. In this ash-pit of cinders, certain ordered routes have been made, thus constituting whatever order there may be—a kind of manufactured chessboard

laid on a cinder-heap.” Ibid., 219. 29 Post-Fordism and its correlative developments was a preeminent topic covered in ZONE 1|2.

Post-Fordism represented a new regime of social, and not only economic, organization that transformed the syntax of how objects, behaviors, and mindsets interacted and formed functional assemblages. Transformation of the relations of signaling and control in producing our lived environments (as normalization of production-line algorithms became universal) certainly began

to register its effects on how books were used and how the mental states that accompanied their use could be incorporated into social production. Flexibility was at that time seen as both a strategy of capital and a tactic of escaping the grasp of its universal grid. In sum, conceiving of the book at this time as a composition of forces in motion, and hence expressing through its example the principle of “continuous modulation” allowed one to claim that it was a map adequate to the reality it engaged by virtue of its capacity for dynamic registration. 30 In the wake of ZONE 1|2 came Rem Koolhaas’s omnibus work S,M,L,XL, which broke not only with the monograph, manifesto, and essay tract model of architectural publishing, but also with the art study such as O. M. Ungers’s 1982 Morphologie: City Metaphors. Koolhaas and Jennifer Sigler, the book’s editor, were among the first tocomprehend the full scope of what had become possible within the activist and pragmatic deployment of the book-city matrix that had been opened up by ZONE,

both in the integration of design as an editorial (illocutionary) force into a book’s content, and in the general freeing up of many of the parameters of a book’s compositional structure for future innovation and development. The selection of ZONE’s designer (Mau) for the project speaks for itself. But, like

Icarus, S,M,L,XL brushed perilously close to the universal solvent of “junkspace”—the amorphous sea, or the “cinders” within which residual contemporary legibility and intelligibility and their attendant freedoms were set to float, and to interact and compound now perhaps only by happenstance and therefore often not at all—and from the brink of this precipice the culture of the book in our profession may yet not have returned. Beyond a certain point, a multipage bound folio is simply no longer—from an “ecology of mind” perspective—a book at all (even if sold and circulated as if it were one).

Sanford Kwinter is Professor of Architectural Theory and Criticism at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. He is a writer and editor, and cofounder of ZONE and Zone Books. His recent books include Far From Equilibrium: Essays on Technology and Design Culture (2008) and Requiem: For the City at the End of the Millennium (2010).