Home Safe

In the winter of 2013, while writing a book about the relationship between burglary and architecture, I met safe room designer Karl Alizade at his New Jersey warehouse. Alizade also works as an insurance investigator for Lloyd’s of London, and at the time his low-slung workshop was filled with evidence from crime scenes that had been sent to him over the years for inspection. There were vaults with their metal backs sawn out; safes with their unhinged doors blasted open; discolored pieces of walls with their inner security panels sliced or burned clean through. However accidentally it had been curated, Alizade’s warehouse resembled an avant-garde installation—somewhere between Sir John Soane’s eccentric collection of architectural fragments and a Gordon Matta-Clark exhibition.

Alizade, a retired police officer with the broad build of a football player, has devoted himself to the challenge of designing the ultimate in burglarproof architecture. As a cop, he had seen first-hand the raw emotional impact of burglary. The threat of having one’s home broken into comes not only with an obvious fear of robbery—that something valuable might be taken from you—but with a much more insidious, existential unease at the prospect that your home is no longer securely your own. Creating a space that was impossible to violate became an obsession for Alizade; it was an engineering challenge as much as a moral goal.

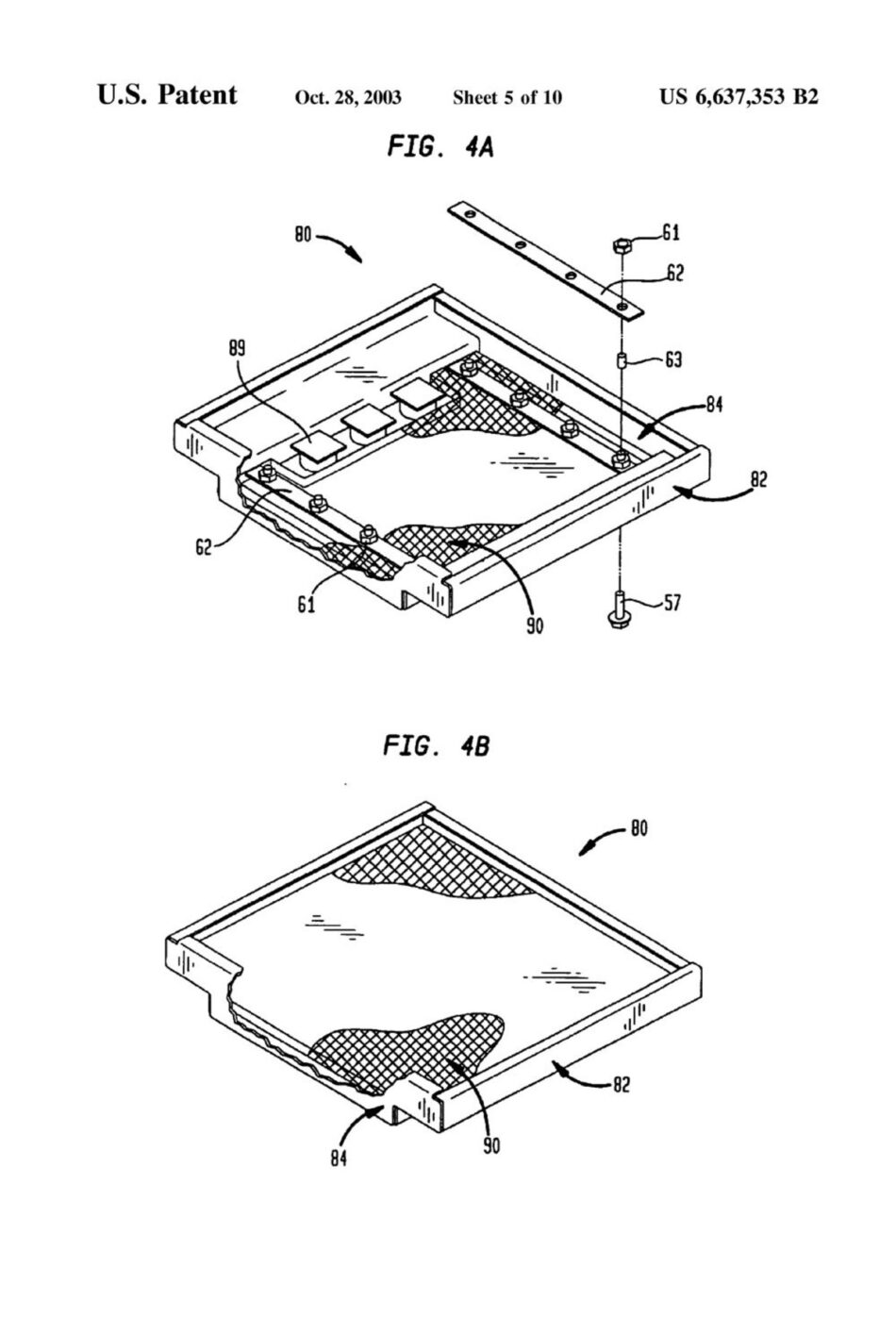

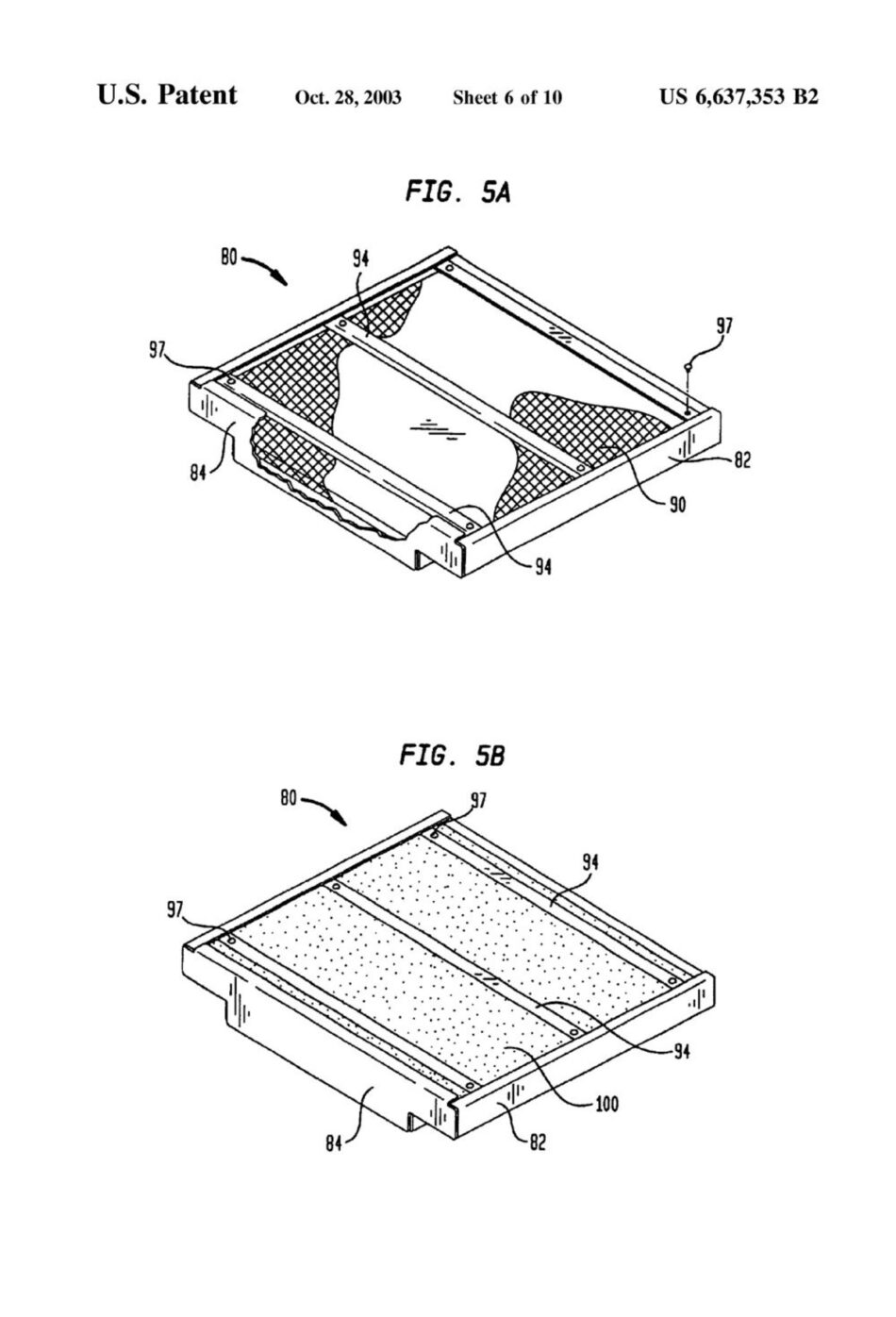

The resulting “safe rooms” (Alizade prefers the term to “panic rooms”) are bolted-together units assembled from individual concrete panels, each about two-feet square. These panels meet along a series of stepped right angles, making them impenetrable to standard burglary tools. The rooms can only be assembled or dissembled from within. As Alizade’s patent diagrams indicate, the genius of the system is its modularity. Customers can let their imaginations run wild, ordering ever more panels, with no realistic upper limit, until what was once a jewel safe takes on the scale of architecture.

Alizade’s system straddles the line between object, furniture, and inhabitable space. Its high price point means that safe rooms remain a luxury for the few, but Alizade is determined to bring the cost down. To date, he has worked with private clients in New Jersey and with the Department of State on sensitive facilities overseas; he has installed safe rooms in mansions and nuclear power plants alike.

A display unit stood in the center of the warehouse. The color of a military ship, it was an imposing behemoth of steel framing and reinforced concrete panels. The walls are impervious to sledgehammers, of course, but can also resist .50-caliber sniper rounds and rocket-propelled grenades. Surrounded by broken vaults and failed walls that looked flimsy in contrast, Alizade’s monolithic safe room was a physical and psychological fortification. Its reassuring bulk welcomed us to step inside and close the door, even as the room’s very existence was an unsettling reminder that are some things are better kept outside.

Geoff Manaugh is a freelance writer and curator, as well as the author of BLDGBLOG, a website about technology, landscape, and speculative architectural design. His writing has appeared in New York Times Magazine, Domus, Volume, newyorker.com, and many other publications. His newest book, A Burglar’s Guide

to the City (2016), explores the relationship between burglary

and architecture.