Performative Rebellions

Performing in the streets of Harlem for the African American Day Parade, the Marching Cobras often appear in standard marching uniforms—plumed hats and double-breasted jackets trimmed with epaulettes. But their movements quickly accelerate into rapid-fire revisions of marching tradition, with drummers and dancers lunging and locking to syncopated beats. Working a range of different drums—enormous over-the-shoulder bass drums, smaller tenor drum sets, higher-pitched snares—the percussionists dip and spin, steadily increasing the speed and intensity of their rhythms. The dance line accentuates the beats with arm swings, deep dips, and body rolls, all the while maintaining tight synchronization and gridded formations. The Marching Cobras, an intensive after-school program for at-risk teenagers in New York, merges systems of physical precision from different time periods: the gridded uniformity of marching-band routines with the artistry of hip-hop choreography.

Marching is a process of iteration. Marching-band performances grow from strict systems of order for synchronizing formations, steps, and rhythms. Against these familiar structures, new interpretations introduce variations, divergences, and disruptions. Each new performance is different—performers, places, and time periods give disparate meanings to the act of marching. Each is an iterative remaking of a historical structure within a new context.

The act of marching in protest is similarly both structured and malleable. Step after step, in a regular rhythm, holding signs, chanting slogans—the physical process of marching is fundamentally repetitive. This movement and, on a larger scale, the march itself repeat and reinhabit previous protests. Both forms of marching appropriate and remake urban spaces, creating new alignments between social groups and spatial boundaries. Marching echoes the linearity and repetition of city streets, but fills these spaces with a tide of synchronized bodies, movements, and sounds. This moving mass creates a momentary social and spatial structure, a materialization of collective identity that aligns with specific buildings and streets. When deployed by marginalized groups, this familiar form can enable otherwise impossible visibility and reinforce entitlement to public space. Both marching bands and protest marches, therefore, offer an ordered structure that can be remade and reinterpreted to serve drastically different purposes. They illuminate the tension between a repetitive historical form and its constantly changing iterations. The historical lineage of marching shows how reinhabiting a familiar form—by changing the who, where, and how of its materialization—can give that form a completely different spatial and political agency.

The mainstream image of American marching bands—animating football games, military processions, and patriotic parades—belies the complex political history of the art form. Within black communities, the adoption of military marching techniques turned the language of a discriminatory government into a tool for cultural and political expression. Dating back to colonial times, when slaves and freedmen were first assigned to the fife-and-drum corps during the Revolutionary War, the techniques of military bands have been continuously transformed to cultivate black public life.1 The War of 1812 led to a surge in black bands, as musicians trained in the fife-and-drum corps used their skills to form civilian bands in northern cities like New York and Philadelphia.2 Membership in these bands granted access to public space, but only within particular northern cities, outside of which performers faced violence and arrest. After the Civil War—the first war in which there were “colored regiments” with their own bands—former soldiers harnessed their musical training to create a wide array of marching bands through the northern and southern states. During the period of Reconstruction, these groups partnered with black benevolent societies to create celebratory fundraising spectacles for communities in the aftermath of slavery.3 The 20th century, however, introduced the most dramatic changes to the music, choreography, and political aims of marching groups.

In 20th-century Harlem, bands continuously reinvented marching rhythms and movements and simultaneously asserted rights to public space. During World War I, the 369th Infantry Regiment of the 93rd Division, or the Harlem Hell Fighters, gained recognition both for their military achievements in France and their famous jazz band. Led by James Reese Europe, the Harlem Hell Fighters Band created jazz interpretations of marching-band music, which became so popular that they recorded multiple records after the war.4 When the Harlem Hell Fighters Band, surrounded by a cheering crowd, marched up 5th Avenue to celebrate victory in 1919, their original music jumped with quick beats, extra trills, and trombone slides. Despite the jubilant atmosphere, their march symbolized a weighty patriotism. As with the 20th Regiment of US Colored Troops marching off to battle in the Civil War in 1864,5 these black soldiers struck an ultimately unsettled bargain with their nation, hoping that their sacrifices would secure their rights to equality, and the act of marching would reinforce their entitlement to visibility and to public space.

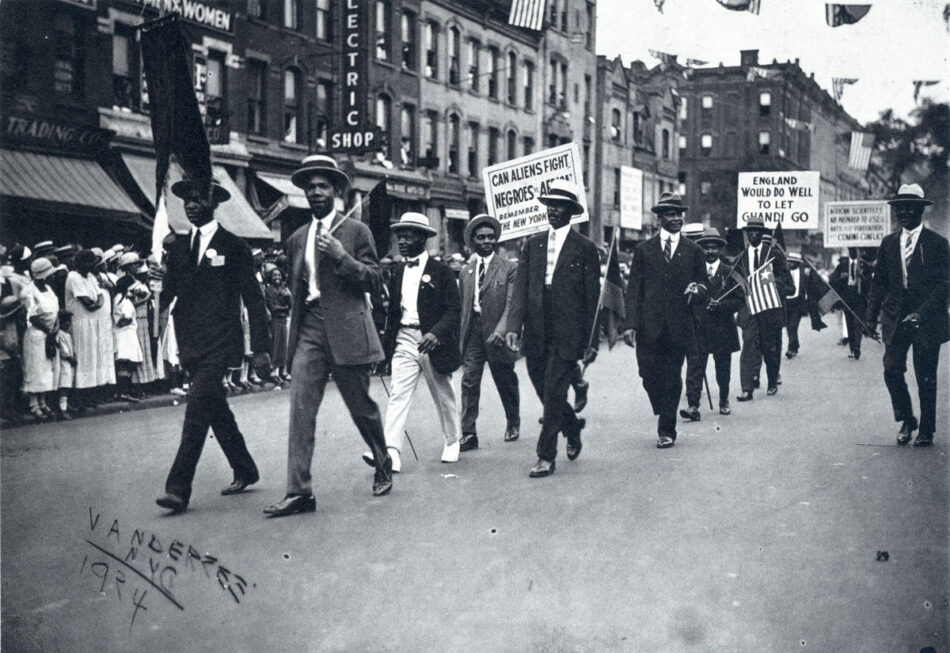

In the years after World War I, marching became an increasingly visible means of asserting political agendas in Harlem. Many cultural and political institutions created their own marching bands for parades down 125th Street, 135th Street, 5th Avenue, and 7th Avenue. Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), which promoted Pan-African pride, regularly paraded through Harlem with its bands in the 1920s. Garvey, who was famous for his booming voice and penchant for regalia, led extravagant parades to rally his political supporters, including multiple brass bands, floats, flying banners, and thousands of cheering followers.6 Meanwhile, the music and choreography of marching continued to shift over the course of the 20th century. Bands from primarily southern historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) created innovative versions of marching-band music and choreography, which were later adopted by northern groups. Beginning in 1946, William P. Foster, director of the Florida A&M University Marching 100, rejected the European model of rigid postures and basic formations, and instead produced choreography with fast high-stepping and complex, curvilinear formations. The techniques of the Marching 100 quickly became popular with all types of marching groups around the country. Contemporary groups in Harlem like the Marching Cobras draw heavily from the theatrical air of the southern HBCU marching bands alongside the beats and choreography of hip hop.

The types of marching bands have multiplied—serving high schools, colleges, churches, and community groups—and their political purposes have become increasingly varied, from celebrating pride to teaching discipline and teamwork. Marching continues in Harlem as a medium for cultural and political expression, especially in the African American Day Parade and Juneteenth celebrations. But the parades are not as common as they were in the first half of the 20th century, and their context is rapidly changing as gentri cation is pushing out long-term black residents and cultural institutions.

As each of these groups created their own version of marching, they did so by repositioning a familiar system. The fact that old-world double-breasted jackets, snare drums, and gridded formations have persisted from 18th-century military parades through to 21st-century performances is not accidental. The continuation of these elements speaks to the usefulness of the historical forms, which offer a structure against which the new variations shine. They also echo the military origins of marching, therefore, intentionally or not, maintaining the political frisson of early appropriations.

The resilience of historical forms also speaks to another kind of invention, different from that which is often celebrated. While creative fields focus on originality as distinct from history, these groups show how innovation can emerge through the reenactment and manipulation of given structures. Alterations to the formal elements of a marching routine—the rhythm, pace, flourishes, and steps—can both maintain and invert an existing structure. Furthermore, alterations to context—the actors, audience, and location—of a performance can entirely resituate its cultural purpose. Marching therefore speaks to creativity and resistance as a form of flipping or doubling, where a familiar element can exist as both its referent and its opposite.

In 1927, the Black Elks’ parade through New York City exemplified how context could shift the tone and meaning of a march, even in the course of one day. Since blacks were excluded from white fraternal societies, the Black Elks was established in 1899, despite threats of lynching, to create a financial and social support system for members. For the 28th annual convention in 1927, the Black Elks held a parade through Manhattan. When the march began at 5th Avenue and 61st Street, it was a solemn procession of Black Elks members in marching uniforms, a display of decorum in front of silent white onlookers. But when the procession rounded the corner into Harlem at Lenox and 110th Street, it triggered an explosion of cheers, applause, and dancing from waiting crowds, with the marchers themselves shouting out to friends in the audience.7 The context of Harlem turned the march from a linear spectacle to an interactive socio-spatial phenomenon, tying together residents and their urban surroundings. In the 1920s, when white shopkeepers, landlords, and policemen held authority over public streets, parades produced temporary suspensions of everyday life, enabling uninhibited celebrations. In Harlem, not only did the context change marching, but marching also changed the context. The interplay between marching and site therefore produced not only iterations of marching forms, but also alternative expectations for public space.

This form of creativity and resistance calls to mind the concept of performativity as articulated by Judith Butler. While focusing primarily on gender and sexuality, Butler’s writing about the appropriation and alteration of social norms is also relevant to this discussion. With regard to gender, Butler argues that the concepts of male or female do not exist as absolutes but rather come into being through individual, daily behaviors.8 Gender is fundamentally unstable because it materializes through the repetition of words, gestures, and postures. Simple movements such as walking or sitting are particular to each person and therefore either reinforce or deviate from expectations for how a gender should behave. This is a form of agency in which social norms are remade through physical embodiment and movement. The act of resistance occurs not through rejecting social norms outright—Butler would argue that it is impossible to get outside of the system that shapes you—but rather by enacting different physical manipulations of a given structure, until the normative concept is destabilized and eroded. The act of citation—the process of embodying a norm—becomes subversive and can steadily undermine established expectations. The physical matter of citation—the people, materials, and contexts—is the means of remaking the original form. The parallel to marching is clear, as successive generations inhabit a system of military movement and deploy it for contemporary purposes of expression and occupation.

Performativity is equally resonant with architecture, where it points to material and corporeal ways of reworking historical forms. Citations of historical references, especially in postmodernism and its recent revivals, are often treated as disembodied images. Forms are abstracted and displaced in the flattened spaces of drawings. But architectural elements, like the techniques of marching bands, do not exist as absolutes but rather as specific materializations. Seeing historical forms as many specific versions undermines any idea of a stable referent. Instead, norms are constantly remade through the sticky tangle of lived experience, in the messiness of human activity and material conditions.

Building on this idea of performativity, Eva Franch, chief curator at Storefront for Art and Architecture, invited me to collaborate with Mabel Wilson, professor of architecture at Columbia University, and the Marching Cobras to create a performance that visualizes and iterates the lineage of marching in Harlem.9 This project brings references to the history of marching—visual emblems, colors, steps, and beats from 1920s marches—into a performance in Central Harlem. In this context, we are foregrounding conditions of transition. From the 17th century to the present, Harlem has emerged from constant demographic and economic change, as successive populations of Native American, European, African American, Caribbean, and Latin American residents have laid claim to its geography. Now, gentrification is enacting a forceful transformation, producing rapid displacements of long-term residents and significant alterations to the urban environment. High-density commercial and residential developments are replacing small businesses on Harlem streets, altering the physical structures and social expectations of public spaces.

Both the performers and the site of the project exist in a state of flux. The young people of the Marching Cobras are teenagers, born at the turn of the millennium and coming of age in the late 2010s. They are moving through adolescence, confronting questions of personal and cultural identity in a heated political climate. The Cobras program—an acronym for Commitment, Obedience, Believe, Respect, Achievement—teaches self-discipline and responsibility as much as performance skills, in two-hour-long rehearsals after school every weekday. The program aims, on an individual level, to work against institutionalized inequality by disseminating life skills and expectations of success. As an art form, their performances merge physical discipline with contemporary expression, crackling with improvised rhythms and hip-hop choreography. Moving at a high velocity, the drummers spin stick tricks and the dancers pop their hips or dive into splits at accelerated tempos. There is a contagious energy to their performances, drawing crowds in public parades and on random sidewalks if they break into an impromptu show. In creating a collaborative performance with the dancers and drummers, we brought symbolic emblems and colors from past marching groups—like the Harlem Hell Fighters and UNIA—and asked them to interpret and integrate these objects and references into their performance. The resulting performance oscillates between traditional systems of marching—with rigid, synchronized steps and drumming—and more contemporary interpretations, with the dancers spinning and dipping to faster-paced beats as they break into curvilinear formations.

Marching in Harlem typically takes place in the street, and is therefore a familiar sight on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard or 125th Street. But this project moves marching off the street, to Marcus Garvey Park, a site of uncertainty. Named for the leader of the UNIA, the square park sits in Central Harlem just south of 125th Street. It has long been a gathering place for an African and Caribbean drum circle but is now surrounded by some of the most expensive real estate in Harlem.10 The drum circle has met most Saturdays since 1969, sometimes playing for 10 hours at a time, creating a hub where people of multiple generations gather. As with marching, drumming enables occupation and transformation of space. But now the drumming brings noise complaints, which raises conflicts between long-term Harlemites and the newer, gentrifying residents.11 With the Marching Cobras performance in the park, the project continues a lineage of occupying public space, and situates that history in a zone of uncertainty. Half-manicured, half-wilderness, the park is an open area that suits the condition of indeterminacy, both of the neighborhood and of adolescence as these young people navigate a changing context for their own identities.

1 The following research into the history of marching bands was gathered with Mabel Wilson with the assistance of Mariam Abd El Azim and Mayra Imtiaz Mahmood. 2 See Jules Allen, Marching Bands (New York: QCC Gallery, City University of New York, 2016), 2. 3 William Dukes Lewis, “Marching to the Beat of a Different Drum: Performance Traditions of Historically Black College and University Marching Bands” (master’s thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2003). 4 Allen, Marching Bands, 4. 5 Alessandra Lorini, Rituals of Race: American Public Culture and the Search for Racial Democracy (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1999), 4. 6 Clare Corbould, “Streets, Sounds and Identity in Interwar Harlem,” Journal of Social History 40, no. 4 (Summer 2007): 876. 7 Ibid., 859. 8 Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (New York: Routledge, 1993), 12. 9 Commissioned by Storefront for Art and Architecture, together we are developing a performance and exhibition, titled “Marching On,” responding to the long history of marching in Harlem. The performance by the Marching Cobras will take place November 11–12, 2017, at Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem, with the support of Storefront for Art and Architecture, Performa, and the Marcus Garvey Park Alliance. An exhibition of the historical research and documentation of the performance will follow at Storefront for Art and Architecture in early 2018. 10 See Tanay Warerkar, “Harlem’s Second Priciest Townhouse Hides Modern Interiors Behind a Classic Facade,” Curbed, New York edition, December 15, 2016, https://ny.curbed.com/2016/12/15/13968008/harlem-second-most-expensive-townhouse-for-sale. 11 See Timothy Williams, “An Old Sound in Harlem Draws New Neighbors’ Ire,” New York Times, July 6, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/06/nyregion/06drummers.html.

Bryony Roberts is a designer and scholar. Her practice, Bryony Roberts Studio, integrates strategies from architecture, art, and preservation to critically engage historical buildings and urban spaces. She has published her research in the journals Future Anterior, Log, and Architectural Record, coedited the volume Log 31: New Ancients, and recently edited a book titled Tabula Plena: Forms of Urban Preservation (2016). She is associate professor at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design and visiting adjunct assistant professor at Columbia University.