Globalization in Time

Tracing the scholarship of Indian American anthropologist and theorist Arjun Appadurai is a study in perspectives on the history of globalism itself. Over the decades, he has vociferously articulated his positions on globalization—as one of the first voices on the subject in the 1980s; through its rise as a concept that simultaneously represented hope and violence, inclusivity and xenophobia, livability and inequality; and now as a spatial concern for planet-spanning issues of climate crises, migration, and public health. More than 40 years after he first rose to prominence with the publication of Worship and Conflict under Colonial Rule, Appadurai joins Rahul Mehrotra in a conversation about the connection between cities and citizenship, new roles emerging for civil society, and rethinking “cityness” from a truly planetary perspective.

Rahul Mehrotra

I thought I would start by seeking your reflections on the moments when you first began to articulate these questions on globalization to where we are now.

Arjun Appadurai

As far as the term, and the idea, and the debate around the word “globalization,” for me, it began in 1990, when I wrote the first essay that became part of Modernity at Large, which came out in 1996. Before that, my colleagues (notably my dear late first wife, Carol Breckenridge) and I had used words like “transnational.” We were struggling to bring in words that moved us beyond the region of the local alone. Around 1987 or 1988, when we formed our journal, Public Culture, the term “globalization” was already in the air, but there was very little handle on it. It was mainly a rather simple journalistic term that meant that borders are falling and markets are growing. It was in 1996’s Modernity at Large that I actually state explicitly, “What does ‘globalism’ mean? What is it about?” And most importantly, “What does it mean to come to that term with an interest in culture, very broadly speaking, rather than simply in markets, or diplomacy, or international issues, or war?”

I would say that this 1996 book was written in a moment of hope. The truth is, if you look at the examples in the book, there’s a lot of critical questions about gender, about diaspora, about the nation. But people read it as an overly positive book. And I took that on board. Over time, I put forward a theory of why this moment—which should have been a moment of opening up—became a moment of closing down. There was too much xenophobia, too much nationalism, too much ethnocide.

So the second phase of my grappling with the meaning of the word globalism started in 2006. It’s not because I was wrong, or anybody else was wrong in 1991 or 1992. It’s just that things have changed. Potentials, which could have gone in either direction, have gone a certain way, so now we have to reflect on that. I have been trying to work in the seesaw between the two sides of what globalization creates. On one side: grounds for hope, in terms of diversity, in terms of inclusion, in terms of livability, in terms of sustainability, almost any value that anyone who is reasonably liberal and progressive would agree on. And on the other side: excess nationalism, xenophobia, closure, violence, inequality. So, in the third phase, which really comes up to today we must ask: How can we stay conscious of the downside without giving up the upside? What are the hopeful grounds? What are the creative practices? What are people actually doing in which we can see possibilities?

Rahul

In the context of today, if we look at what happened with the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, we seem to have gone beyond globalization and up to the planetary scale because it links us all. New politics are emerging, with the poorer nations demanding assistance from richer nations. And richer nations are accepting the interconnectedness of our existence on the planet. What are your thoughts on how that will play out? Is this an extension of the notion of globalization as you were defining it? Or is this some kind of new formulation?

Arjun

You’re right: we are at the end of the era of globalization because it’s been supplanted or superseded. It’s not that it’s disappeared, but it’s somehow a smaller picture. “Planetary” now means we need to go beyond the surface of the Earth. It’s become galactic or somehow into space. Whether it’s UN Secretary-General António Guterres or others, people are really trying to come to terms with the idea that our problems are planetary in a sense that is not captured by the word “global.” The climate, migration, viruses: these issues no longer have to do with markets, or 1989, or the Wall coming down. It’s some other reality.

Now I’m trying to take on the planetary, having spent a very long time thinking about the global. I’m on the trapeze; leaving one side and hoping to catch the other end.

Rahul

What is the agency that education, architecture, planning, or design more generally might have in this condition? How do we make an intersection between our spheres of concerns and our spheres of influence? Because clearly what you’re saying is our spheres of concerns have exponentially expanded, and are almost infinite now—while in some ways our sphere of influence is diminishing.

Arjun

This is another deep question. So why are students coming to schools like the GSD? What do we owe to them as people who can claim a serious credential? One answer would be, Let’s remember that we are also craft people. We make designs. Architecture means something specific. But that is actually a conservative response because it ignores one side of what I think is the dual reality, which is that not only does an object change from the point of view of where we are seeing it, but we observers also change.

To me, that’s the deep pedagogical and curricular challenge. I’ll offer one metaphor that relates to what you said about how the planet is expanding and our influence is shrinking at the same time. Which is to say, we have to leverage the fact that we are all now keyholes. We look through a small keyhole, but we see a huge panorama. The keyhole will remain small. But the thing is, you can redesign the keyhole. You can’t pretend that it’s suddenly a Hubble telescope, which can see the whole galaxy. But the keyhole can be adjusted, and all our design disciplines are like that.

Rahul

Over the years, you have situated the human in the question of pedagogy. I was remembering how, at one of your lectures at the Asiatic Society of Mumbai, you made a call against “weapons of mass construction.” As someone who was involved in planning and architecture in India (and in Mumbai, more specifically), I understood it as your calling to us to resist the global flow of capital and neoliberalism, which you believed were going to dissipate the fabric of our city in a bizarre way. And a little earlier, you and Carol Breckenridge started PUKAR, one of the most significant civil society formations in Mumbai. Literally translated, it means “a calling,” but it stands for Partners for Urban Knowledge, Action and Research. What you are doing with PUKAR is quite different from just using the city as a lab or as an observatory; it is motivated by action and change. Can you tell us what inspired you to create PUKAR? I would love to hear your thoughts on the question of pedagogy, and also how PUKAR is situated within that landscape.

Arjun

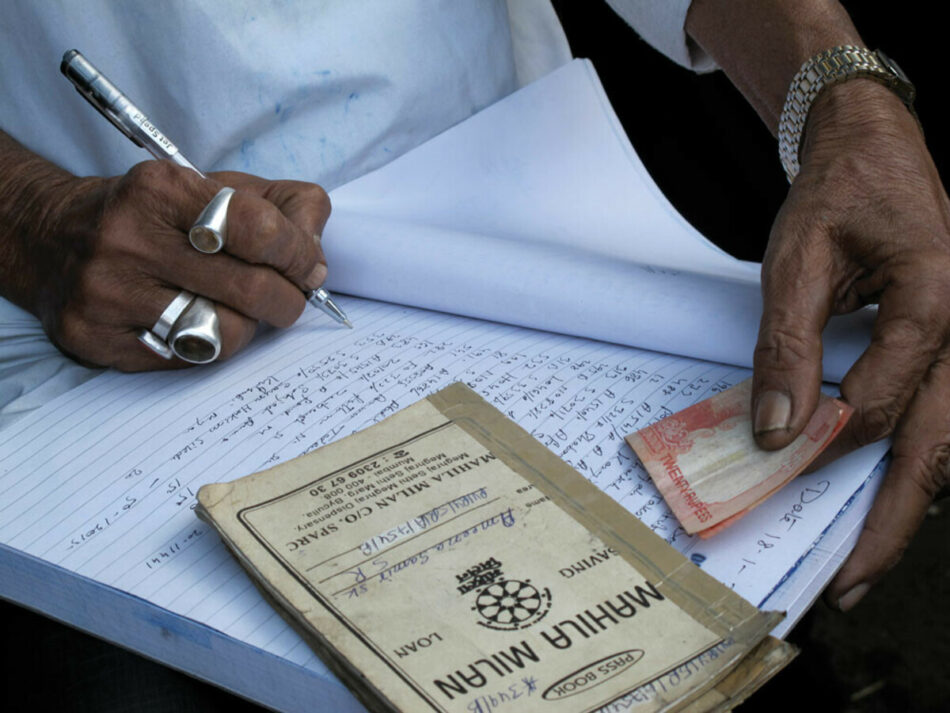

With PUKAR, we reach out to non-Anglophone, non-privileged populations to teach them certain skills, particularly so-called research, which is normally seen as the preserve of very high-end scholars. If you don’t have that background, how do you learn to frame a question, define what data is needed to answer the question, and make the question falsifiable? We began with Rahul Srivastava’s idea of documentation as intervention.

With this method, all you need to start is to tell your story. You could be a rag picker and you have a story. Once the story is out, a dialogue begins: “Well, why did your dad do that?” “Why did you leave your village home?” “How did you get to the city?” One question leads to another. If you are 17 or 18 and you’ve survived, then PUKAR is trying to help you figure out how to use the story and make it into a method and then into a theory. First you have your story, but everybody has a story. So, your claim to the city is as good as anybody else’s.

And that leads me to mention the connection between cities and citizenship. These two words have a connection. But there is less work on that connection. There’s a ton on cities and there is a ton on citizenship, but let’s talk a little bit about the connection.

Rahul

That makes me think of your other rather wonderful formulation of the idea of “deep democracy,” where you argue for new roles for civil society. You emphasize the role of making the connection and representing the grassroots, but also having the ability to negotiate with more powerful forces. It’s also about going from the critical to the propositional, but with a mindful engagement to a certain set of values and questions that emerge from putting the idea of citizenship at the center of that discussion.

Arjun

There needs to be some kind of participation, which is not just physical.

Rahul

Exactly. So there are implications for this kind of meso space—the space between high theory and grounded practice. In fact, for me, that has been a seminal influence in our discussions and the work you’ve done. How do you see the relevance, the potency, the instrumentality of thinking about this meso space? And what might its implications be on pedagogy?

Arjun

These are the questions we are all struggling with—whether we are in NGOs or whether we are in design schools or whether we’re just trying to understand the city or understand global processes. These are the most difficult and challenging issues that don’t respond to a formula or to an available algorithm.

The question is how do you push the other party to the highest ideals—whether you are on the activist side or on the theory side, or in architecture, where you are in the mix already—because you’re trying to make solutions that are real. But you also have privileges of analysis and understanding that ordinary people, poor citizens, slum dwellers, don’t have. So, the first thing is, how do we push all sides to go to where the oxygen is thin? That’s when the conversation finally goes beyond a pleasant chat. That’s when things get real.

In my own field of anthropology, there’s been a tendency to overvalue so-called Indigenous knowledge. We’ve spent a lot of time saying, “Just go and ask the people, the people know.” But the point is that the people are suffering like hell. So, it doesn’t matter what they know; there is a disconnect between what they know and their situation in life. Whether you are slum dweller in Mumbai or somebody herding pigs and growing yams in Papua New Guinea, there is no point in fetishizing what anybody knows already.

So to me, that’s the frame in which teaching or pedagogy has to occur, whether it’s with students in Mumbai or at the GSD. They have to understand that they have to shift their sense of superiority, but also that the people on the ground don’t know everything already.

Rahul

And so do I understand this correctly—that occupying the meso space is not only the privilege of the professional; it’s the privilege of anyone who has the ability to construct appropriate knowledge for that condition? Is that a correct framing?

Arjun

I haven’t thought about it in this way, other than in this conversation, that this meso space—which is a pedagogical space, which is an intervention space—is also a kind of no-man’s-land, because nobody owns it. There’s no sovereignty over it. In order for it to be fruitful, and not just a domain of battle and anger, it has to be in the spirit that we are co-designing in the deepest sense possible.

Many, many endeavors fail in anthropology. For example, the idea of the “informant”—there’s something about that, which is not exactly democratic. And I’m sure there are equivalences in design, where someone is already placed in the role of being a means to your end. The question is, can you share the end? Can you collaborate on the ends?

Rahul

That’s right. We often fall into biases through the use of mediators: through the choice of the mediator and the meaning of the mediator. Is that what you are alluding to?

Arjun

Yes. I suppose you could say that. Every time somebody says they’re a mediator or a broker or a dalal, there is a sense that the playing field is even, but often it’s not—

Rahul

There are exclusions and, on the other side, biases too, correct?

Arjun

In other words, they actually entail one another. The bias, you might say, produces the exclusion. Exclusion never happens on its own. So I think the bias, and that’s a very good way to put it, is different from the exclusion, but they have a relationship worth examining.

Rahul

I agree. So to bookend this conversation, Arjun, which has been wonderful, I’m going to pick up on your reference from right at the beginning when you mentioned Public Culture, the journal that you established with Carol Breckenridge in 1988. It has been analyzing the cultural politics of globalization for over 30 years. What is interesting is that in 2020, after a gap of more than two decades, you have reengaged with the journal. And now you are involved with another generation of scholars, with different lenses, who are looking at how globalization and its disruptions or its productive dimensions are playing out. I would be very curious to know how those sorts of perspectives have changed and to hear what you are seeing in contemporary or global culture today.

Arjun

Public Culture is, above all, very interested in the heartbeat of what is happening, not in some dogmatic position out which we then want to squeeze every bit of information. We really want observationally driven insights. We don’t always succeed; but that’s what we seek and that hasn’t changed. But as we’ve just discussed, the world has changed in many ways.

Let me just pick one thread out of that huge fabric of change. Depending on one’s field and interest, there are many ways to pick a thread. But one thread is media studies. The department in which the journal is now housed is the one I’ve just retired from: Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University. It’s an interdisciplinary department. It’s a little bit like the GSD in that everybody has a common object, but if you forced everybody to define it, there’d be a lot of bloodshed. There are political scientists, anthropologists, humanists, literary scholars, scholars of cinema. The main thing that unites them is that this is a place to learn about theory. So all of these faculty, they’re not practitioners. That’s a difference from the GSD. They’re not primarily teaching people to make something: they’re teaching people how to think carefully about media and our contemporary world.

Rahul

So with this new generation, what are the other issues on the ground that you are seeing in terms of globalization today? And are there things that we perceived as disruptions 30 years ago within this rubric of globalization that are productive in other ways now?

Arjun

At Public Culture, we are finishing the curation of quite a large number of contributions. They are from urbanists from all over the world—some of whom are designers, some of whom are urban scholars—of various generations. But typically not much older than 50, and then going down from that.

What I’m seeing is that a certain number of key concepts like territory, sovereignty, property, are now bursting out of the container that we put them in. And that is because, empirically, that container is leaky.

So here is what I’ve come away with, which I’ve shared with my colleagues. Many of us have spent three, four, or five decades thinking of urbanity or cityness in terms of concentration. My proposal is that we start thinking about cityness in terms of dispersion, instead. Cities are not about more people, more relations, more density.

Density, in other words, is not just physical, it’s also sociological. If we stay stuck in the concentration model, we won’t be completely wrong, but we’ll be missing something that I think is more and more true. We’ll be missing contemporary issues related to financial, climatic, and other global processes. But as I say, the short formula is: think dispersion, not concentration. We must pull against everything we’ve been trained in.

Rahul

That’s a potent provocation to end this conversation and a wonderful note to conclude on. Many thanks.