The Past in the Present

In an office park in suburban Los Angeles, set within a pristine landscape garden designed by Isamu Noguchi, there is a funny monument made of piled stones; the artist dubbed it The Spirit of the Lima Bean (1982). Back in the heyday of allegorical sculpture, at the turn of the past century, citizens were likely to encounter the Spirit of Truth, or the Spirit of Fire, or maybe even the Spirit of Electricity—but never the spirit of an ordinary legume. Yet Noguchi’s lima-bean monument is more than a joke on an old sculptural genre; it gestures to a lost way of life from the Southern California of his youth. If the lima bean lives in spirit in this garden, the nearby farms that once produced actual lima beans are long gone, victims of a relentless process of displacement in which Noguchi’s own work participates.

The Life of Memorials

The Spirit of the Lima Bean could easily stand as an emblem for a whole school of thought that sees modern collective memory as a phenomenon of rupture and loss. According to this school, only when the past has slipped away—becoming a “foreign country” in David Lowenthal’s famous phrase—do we begin to mark and commemorate it. Or to paraphrase Pierre Nora, it is when we stop experiencing memory spontaneously from within that we begin to “design” memory, to create its external signs and traces, such as monuments and museums and historic buildings.1 According to this way of thinking, the intensifying proliferation of the external signs of memory in the contemporary built environment signals the death of a more organic cultural memory that supposedly existed in the hazy premodern past. Thus we can add “the death of memory” to the other assorted deaths—of art, of the author, etc.—that cultural critics have been eager to identify.

But if this sort of lament is increasingly common, we often fail to acknowledge its long genealogy. Long before Robert Musil declared that “there is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument,”2 many observers were complaining that public monuments were inert, even “dead,” worth little by comparison to a memory that “lived” within people’s hearts. Ironically, even at ceremonies marking the construction of public monuments, this sort of rhetoric became commonplace. As the orator at the 1867 cornerstone-laying for the first soldiers’ monument at the Antietam battlefield affirmed, “Let statues or monuments to the living or the dead tower ever so high, the true honor, after all, is not in the polished tablet or towering column, but in that pure, spontaneous, and unaffected gratitude and devotion of the people that enshrines the memory of the honored one in the heart, and transmits it from age to age long after such costly things have disappeared.”3 This idea dates back to Pericles’s famous funeral oration for the Athenian war dead, in which he argued that the most distinguished monument is the one “planted in the heart rather than graven on stone.”4 The contrast between heart and stone—between spontaneity and fabrication, feeling and obligation—obviously calls into question the authenticity and efficacy of built forms of remembering.

Embedded in the very process of memorial building, then, is a longstanding anxiety about monuments. Today, as we are experiencing an explosion of interest in erecting public monuments, it is useful to explore whether this anxiety is still—or was ever—justified. Of particular interest to me are the new monuments to the Civil Rights movement, because they revisit many of the issues—stated and unstated—that we as a nation struggled with at the end of the last century in trying to come to grips with the legacy of the Civil War.

Why lavish time and money on monuments, especially if “true” memory indeed resides elsewhere? During the great age of the public monument in the United States, from the mid-19th through the early 20th century, monument proponents were armed with a well-rehearsed response. Monuments did not replace the “true” memory within people’s hearts, they claimed; rather, monuments were tangible proof of that inner memory. Thus were monuments construed as the most conspicuous sign that a national people understood and valued its own history.5

In the United States, the dominant notion of history has been that of a people dedicated to progress. Public monuments helped to celebrate and cement this progressive narrative of national history. To do so, monuments had to instill a sense of historical closure. Memorials to heroes and events were not meant to revive old struggles and debates but to put them to rest—to show how great men and their deeds had made the nation better and stronger. Commemoration was a process of condensing the moral lessons of history and fixing them in place for all time; this required that the object of commemoration be understood as a completed stage of history, safely nestled in a sealed-off past. Until the 18th century, statues were made of living kings, a practice that continued in the early years of the United States when the state of Virginia erected Houdon’s statue of George Washington in 1796, three years before his death. By the 19th century, however, it was generally believed that monumental heroes—like Noguchi’s lima bean—should be dead and gone, their life histories closed.6 (At Washington’s death, some writers rejoiced that now he could do nothing to tarnish his reputation; it was safe for eternity. They could not foresee that DNA testing might alter a president’s reputation two centuries years after his death.) Similarly, historical events had to be decisively over: wars won (or lost), acts of statesmanship consummated.

This logic of commemoration drastically shriveled history. Women, nonwhites, laborers, and others who did not advance the master narrative of progress defined by a white male elite had little place in the commemorative scheme, except perhaps as the occasional foil by which heroism could be better displayed. This kind of commemoration sought to purify the past of any continuing conflict that might disturb the carefully crafted national narrative. Perhaps the most dramatic example of this in the United States is the commemoration of emancipation in the aftermath of the Civil War.

The abolition of black slavery in 1865 constituted more of a beginning than an end—the beginning of a long period of intense contestation over the meaning of “freedom” that would, at the end of the 19th century, culminate tragically in a renewed era of the repression of African Americans. Yet as early as 1866, designers of monuments were proposing to “commemorate” emancipation in the form of monuments to Abraham Lincoln. To become an object of commemoration, emancipation needed to be understood as a finished act rather than an unresolved process. Thus the struggle for freedom was condensed into a single human decision—Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation—even though this action freed only the slaves in Confederate territory, leaving slavery intact in the Union. Similarly, the decisive role played by slaves themselves in their own liberation had to be repressed for two crucial reasons: their actions distracted from the main point of the historical episode, which was the moral glory of the white leader; and their historical struggle against slavery prefigured their continuing struggle for equal rights. A complex and disputed historical process was thus reduced to the stroke of a pen and the waving of a piece of a paper, a work of individual, isolated genius. Most notorious of the memorials that embody this flawed understanding is the so-called Emancipation Monument in Washington (1876), funded but not designed by African Americans; in this monument, a standing Lincoln with one hand on the proclamation appears to be blessing a kneeling slave whose chains have been magically sundered.7

By trying to lock up the past in a prefabricated narrative of progress, monuments such as these can, as Lowenthal and Nora suggest, work to destroy the sense of a past that still lives within us—a past that helps us define the problems and opportunities we face in the present. Yet the processes of making and experiencing a public memorial always have the potential to undermine the monument’s appearance of fixity. The world around a monument is never fixed. The movement of life causes monuments to be created, but then it changes how they are seen and understood. The history of monuments themselves is no more closed than the history they commemorate.

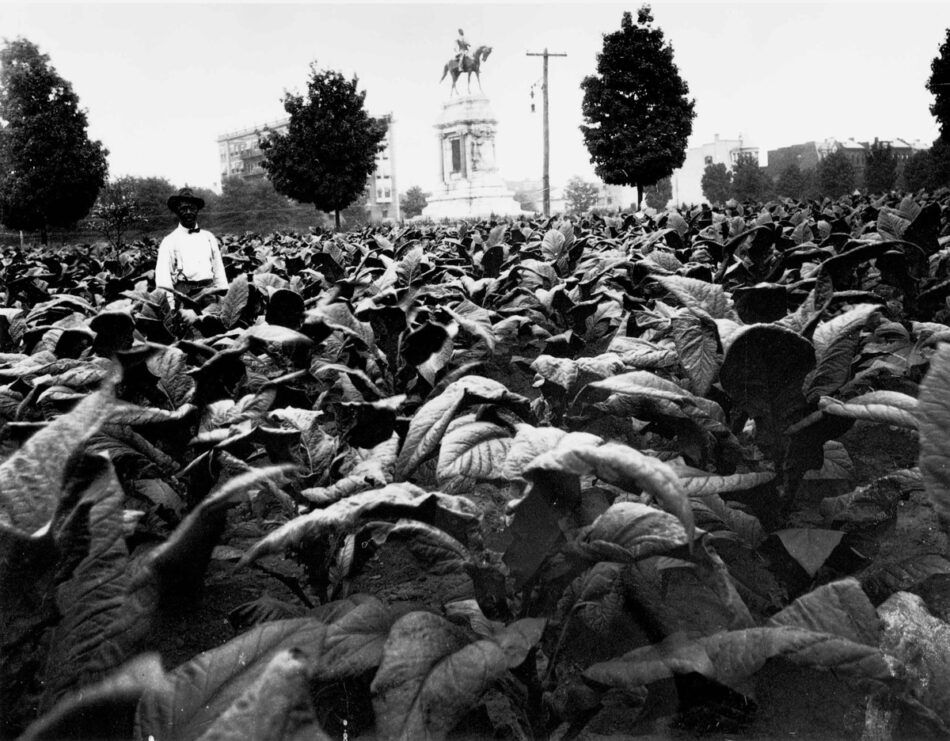

To see this at work, we need only glance at Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, which, since the Civil Rights movement, has become a locus of great controversy. This stately boulevard takes its name from the five colossal monuments to Confederate generals and leaders erected along its length between 1890 and 1929, the first and most prominent an equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee. The Lee Monument and its successors worked to strengthen a canonical narrative of the Confederate past—a saga of white valor and statesmanship. The closure of history embodied so effectively in these monuments was part of a larger strategy engineered by the white elite to legitimate its authority in the so-called New South. Sensing that a threat to the avenue’s Confederate integrity would be a threat to this version of history, the avenue’s defenders long claimed that it was a sacred precinct and therefore exempt from historical processes of change. But like all monumental precincts, Monument Avenue has no choice but to participate in history. The avenue originated in a real estate scheme supported by a nephew of Robert E. Lee, and from the first it was embroiled in local and state politics.8 When the black majority finally took control of local government and an African American was elected governor in the late 1980s, the Confederate bastion began to crack. A protracted battle ensued when various proposals were made to place monuments to civil rights heroes on the avenue. Ultimately the battle ended in compromise: the African American chosen for commemoration was black tennis star and native son Arthur Ashe, whose monument was erected in 1996 and located just beyond the five Confederate statues. Although not a political figure, Ashe was an educated and articulate African American who spent his last years campaigning for better AIDS education. The white Richmonders who fought the Ashe Monument worried, rightly, that its presence would profoundly alter Monument Avenue. Now the procession of Confederate heroes, icons of white supremacist rule in Richmond and the New South, culminates ironically in an emblem of exactly the sort of black citizenry the Confederacy feared, outlawed, and fought.

But the battles are far from over. Recently, a large portrait of Robert E. Lee was hung on a new riverfront walk in Richmond, only to be removed because of protests from African-American leaders. While the protesters asserted that Lee had fought to keep their ancestors enslaved, the Sons of Confederate Veterans argued that Lee was “a hero of all Virginians” and that removing his picture was a “desecration.”9 This dispute is similar to one that occurred in 1871, when white legislators moved to purchase a portrait of Lee for the Virginia State Capitol, and it recalls scattered protests that took place as the Lee monument was being constructed.10 These disputes remind us that there is no single or unified experience of a commemorative image, and conflict often centers on whose experience the image tacitly recognizes and legitimates.

The essential problem is not that “true” inner memory has disappeared, as Nora would assert. On the contrary, inner memory is alive and kicking: it is the force of living memory that makes the external forms of commemoration meaningful and controversial. The historical memory of the Confederacy is profoundly fractured, and its competing versions continue to be nourished by organizations dedicated to remembering as well as by the oral traditions of families descended from slaves and soldiers alike. Commemorative imagery always has the potential to bring these less visible currents of memory into public contention. For a century, Confederate sympathizers had a near monopoly on public memory in the South; having now lost that monopoly, they are trying to position themselves as “Confederate Americans” with their own right to representation in a multicultural society.11 Their new ethnic posture is disingenuous, however, given their continuing efforts to claim Lee as a hero for everyone. Lee can be their hero but he is not an African-American hero, nor will he be as long as the memory of slavery remains a vital part of the African-American community.

The Civil Rights movement is a more recent, indeed personal memory for its surviving participants; but the commemorative issues it raises resemble those of the Civil War. As an object of commemoration, the Civil Rights movement would appear to offer an ideal opportunity to improve on the dismal precedent of emancipation. The public realm is far more accessible to African Americans today than during Reconstruction, when they had virtually no opportunity to influence the design of any public monument, even those they funded themselves. Today African-American communities not only are acknowledged as monument consumers, but they also have the political leverage to sponsor and design public monuments. Still, the commemorative enterprise of our own time presents a striking parallel to the dilemma posed by emancipation. The 20th-century movement for civil rights picked up where emancipation left off, and this long continuous history remains unfinished. While the civil rights era has its martyrs, milestones, and tangible accomplishments that provide grist for the commemorative mill, the movement has evolved, fractured, and continued to struggle toward the elusive goal of racial equality. The legacy of the movement’s heroic past continues to be disputed in conflicts over affirmative action, school and housing desegregation, and economic opportunity. The key question then becomes: will commemorating this heroic past make it recede further from the present, or can commemoration challenge us to grapple with that past’s complicated legacy?

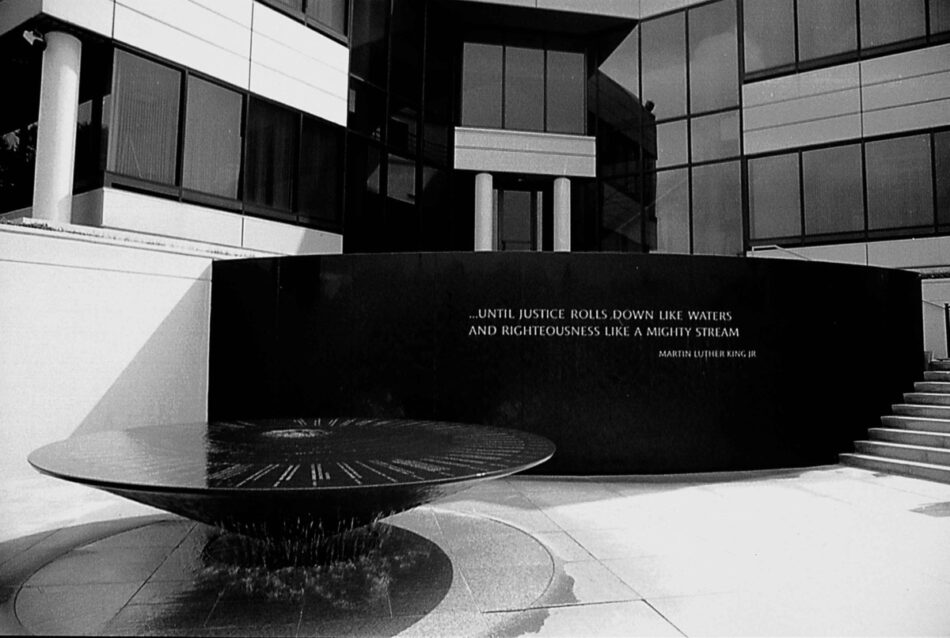

Much of the civil rights memorial activity has been in Alabama, where monuments erected over the past decade run the gamut of commemorative solutions. At one extreme is Maya Lin’s memorial at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery: abstract, contemplative, anchored by its elegant presentation of objective historical fact. Against a backdrop inscribed with Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famous words, “until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream,” a black marble “table” bathed in water displays a circular time line of events from 1954 to 1968, with the names of several dozen martyrs interspersed with a record of judicial decisions and political actions. Like her Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, the Civil Rights Memorial condenses historical process into a sequence of verifiable events and sacrifices with a definite beginning and end; interpretation of this “closed” historical period, however, is left to the individual viewer who is encouraged by the flowing water and the serene surfaces to reflect on history’s meaning.12

At the other extreme is a group of figurative monuments in Kelly Ingram Park in Birmingham, which try to draw the viewer back into the tumult of the past. Several works designed by James Drake along a path named Freedom Walk commemorate the brutal police repression of the famous marches in the spring of 1963. In one work, the walkway passes between two vertical slabs, from which bronze attack dogs emerge on either side and lunge into the pedestrian’s space. In another, the walkway leads through an opening in a metal wall faced by two water cannons; just off the walk, by the wall, are two bronze figures of African Americans, a man crumpled to the ground and a woman standing with her back turned against the imagined force of the water. Integrated into the pedestrian experience of the park, these monuments invite everyone—black or white, young or old—to step for a moment into someone else’s shoes, those of an innocent victim of state-sponsored terror.

At first glance, Drake’s works appear to direct the viewer’s experience more imperiously than Lin’s does. But Lin’s memorial to the Civil Rights movement is far more of a guided experience than her earlier memorial to Vietnam veterans. While the Vietnam Memorial is notable for the absence of any statement glorifying the cause or linking the war deaths to any lasting achievement, the Civil Rights Memorial obviously valorizes its cause with the quotation from King, and its time line links human sacrifices to tangible accomplishments. At the Vietnam Memorial, the absence of customary explanations of warfare and death forces the visitor to supply her own. In the Montgomery monument, the moral of the story is already part of the package. Yet aspects of the monument work against this neat closure of history. The very circularity of the time line is ambivalent: on the one hand, it suggests completeness; on the other, return and repetition. Unlike a textbook time line, that of the memorial is neither linear nor progressive. And it ends not with an accomplishment but with King’s assassination, a tragedy whose implications remain to this day unresolved. Unanswered questions are formulated. Where might we have gone with him? Where have we gone without him?

For all their obvious drama, Drake’s monuments are unpredictable in their impact. In a sense, they are victim monuments: they do not represent the human victimizer but instead position the viewer as the target of his unseen evil.13 No single critic can hope to explain or even describe how such a monument affects viewers. As visitors assume the imagined position of the victim, they do not leave their own selves, their inner memories and life experiences, behind. While the monuments are supposed to make history seem less remote, they might have the opposite effect on some visitors, who might see them as emblematic of a barbaric past, long gone. Others might wonder whether the abuses of the past have been rectified; they might connect the repressive tactics of the early ’60s with the police brutality that has lately been so much in the headlines. Some might leave Kelly Ingram Park with the message that the fight is behind them; others might feel inspired to continue the struggle in new ways. These simple predictions don’t even begin to exhaust the possible divisions—based on race, class, gender, political persuasion, life history, and so on—that can inspire radically different responses to the same work.

The design of public monuments is obviously important; but design cannot claim to engineer memory. The inner memories of a culture profoundly shape how its monuments are experienced and lived. The fate of the civil rights memorials will ultimately depend upon how the movement itself is remembered and reinterpreted in the complex reality of the present. In this light, one of the most promising projects is one not yet designed. Last year in Wilmington, North Carolina, a coalition of politicians, business leaders, citizens, and academics sponsored a year-long series of community events and small-group dialogues to commemorate and reexamine one of the most shameful episodes of Southern history: the white supremacist riot of 1898 that destroyed the local black press, attacked black businesses, and forced a legally elected interracial administration to resign from power. The centennial observances in 1998 were partly about history—about setting the historical record right, giving the African-American community the opportunity to voice its own “inner” memory of the past handed down over generations. But even more important, the observances were intended to create a framework for the future based on ongoing dialogue, mutual understanding, and community action. Dozens of interracial discussion groups, each with a trained facilitator, met for a year; local institutions such as the police, banks, and chamber of commerce reevaluated and revised their practices. A monument has been envisaged as one part of this broader effort.14 Whatever its design, its success or failure will inevitably be linked to the success of the city’s campaign to recast itself. The experience of the monument—the “lesson” of the monument—will be affected by the community’s efforts to bridge the racial divide. If this North Carolina city can work toward genuine racial justice, then the monument commemorating this struggle will not become an obsolete marker of a disconnected past but an agent of consciousness in a changing world.

Kirk Savage is associate professor of art history at the University of Pittsburgh. He is the author of Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America.