Ozzie and Harriet in Hell

Once upon a time, a placid town, celebrated in millions of picture postcards, basked in the golden glow of its orchards. In the 1920s it was renowned as the Queen of the Citrus Belt, with one of the highest per capita incomes in the nation. In the 1940s it was so modally middle-class—the real-life counterpart of Andy Hardy’s hometown—that Hollywood used it as preview laboratory to test audience reactions to new films. In the 1950s it became a commuter suburb for thousands of Father-Knows-Bests in their starched white shirts.

On the Decline of Inner Suburbs

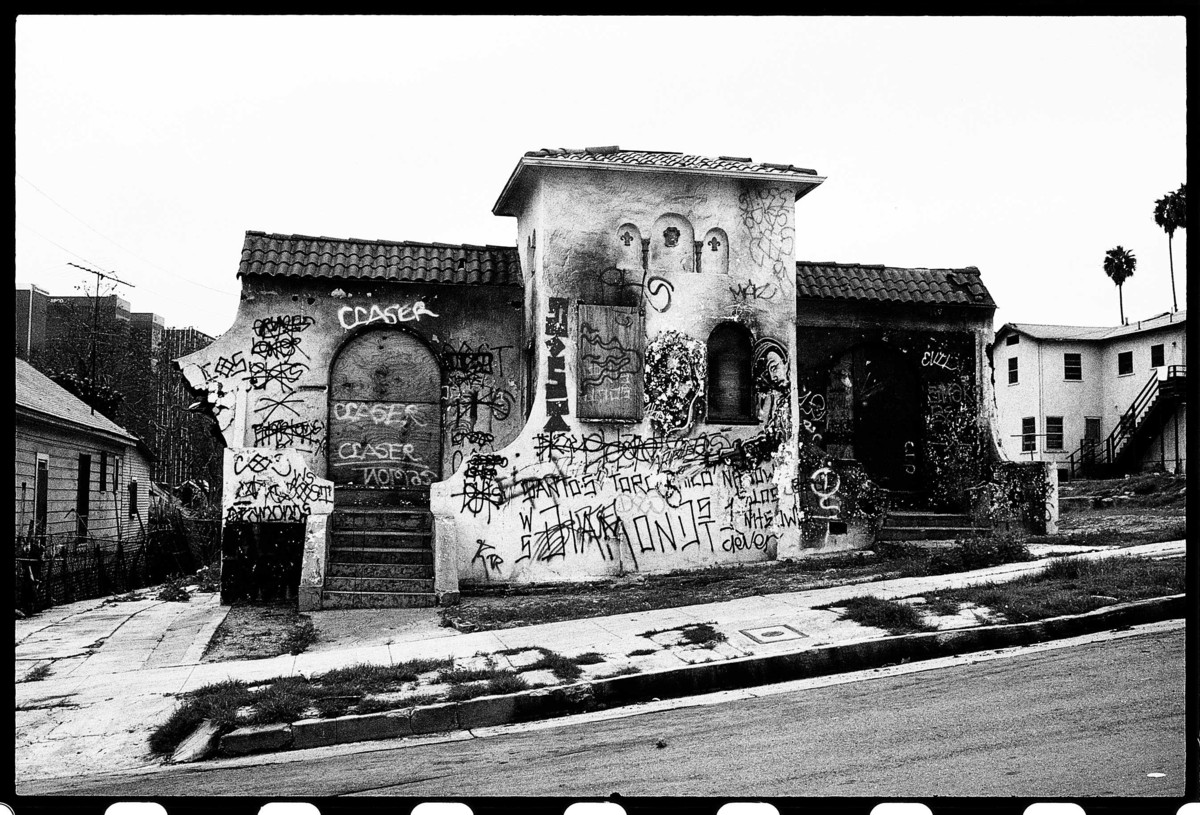

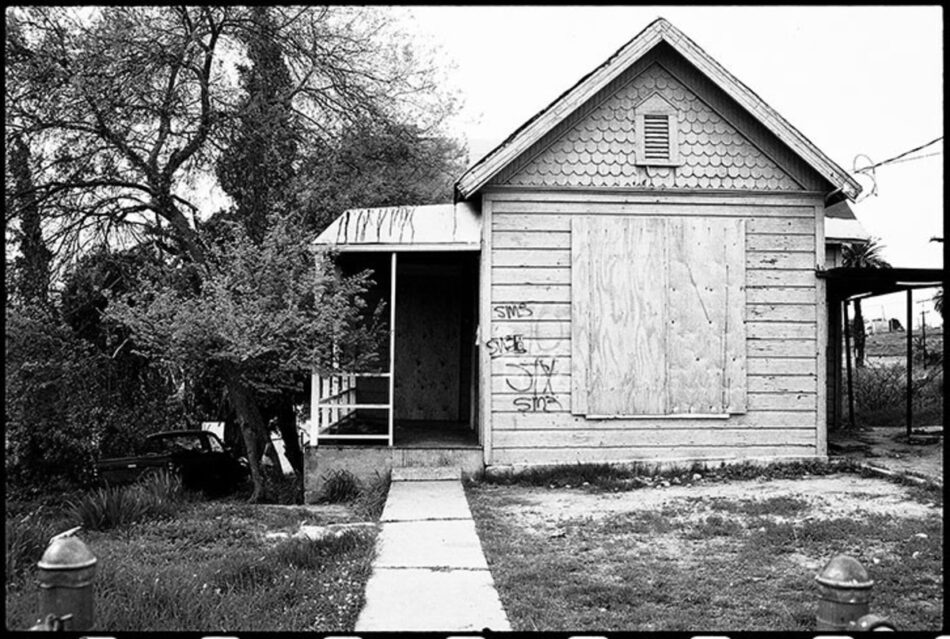

Now its nearly abandoned downtown is surrounded by acres of vacant lots and derelict homes. Its major employer, an aerospace corporation, pulled up stakes and moved to Tucson. Its police department has been embroiled in a long scandal over charges of racism and brutality. The 4H Club has been replaced by local franchises of the Crips and Bloods. Since 1970 nearly 1% of its population has been murdered.

“It” is Pomona, Los Angeles County’s fourth largest city (population 134,000). Although geographically a suburb in outer orbit, it displays most of the pathologies typically associated with a battered inner city. What “plays in Pomona” now is mayhem and despair.

Its incidence of poverty, for example, exceeds Los Angeles’ and its homicide rate, in bad years, approaches Oakland’s or Baltimore’s. Its density of gang membership, as a percentage of the teenage male population, is one of the highest in the country. Likewise, a 1993 survey of 828 communities ranked Pomona as the eleventh worst in the nation for the welfare and health of children. In some of its schools, 80% of the students are poor enough to qualify for free lunches. According to 1994 statistics, one-third of Pomona Unified School District’s seniors fail to graduate each year — ten times the rate of the neighboring college community of Claremont.

Years of urban renewal, meanwhile, have left its downtown as desolate as a miniature Detroit, while its proudest achievement—the tax-subsidized development of a walled, upper-income neighborhood known as Philips Ranch—has only exacerbated the sense of disenfranchisement in poorer areas like the “Island,” “Sin Town,” and the “Flats.” Although now the mayor is a Latino (he is also a Mormon and Republican), real power in this majority Latino and Black community is still firmly monopolized by the Anglo business elite—grandchildren of wealthy orchard owners—who live in the big houses “on the hill,” in Ganesha Heights.

Unfortunately Pomona is not a unique case. Across the nation, hundreds of aging suburbs are trapped in the same downward spiral from garden city to crabgrass slum. It is the silent but pervasive crisis that dominates the political middle landscape.

Needless to say, the arrival of a second urban crisis—potentially comparable in magnitude to the seemingly endless ordeal of American inner cities—does not fit comfortably into either political party’s current agenda. Although urbanists and local government researchers have been screaming at the top of their lungs for several years about the rising distress “in the inner metropolitan ring,” most politicos have kept their heads buried deep in the sand.

The failure of candidates to address, or even grasp, the acuity of the suburban malaise explains, in turn, much of the populist rage that currently threatens the two-party status quo. America seems to be unraveling in its traditional moral center: the urban periphery. Indeed, the 1990 Census confirms that 35% of suburban cities have—experienced significant declines in median household income since 1980. These downward income trends, in turn, track the catastrophic loss of several million jobs, amplified by corresponding declines in home values and fiscal resources.

As a result, formerly bedrock “family-value” towns like Parma, Ohio (outside Cleveland), or University City, Missouri (outside St. Louis) are now experiencing the social destabilization that follows in the wake of the relentless erosion of traditional job and tax bases. As the National Journal tried to warn largely inattentive policymakers several years ago, “older working-class suburbs are starting to fall into the same abyss of disinvestment that their center cities did years ago.” The tables have been turned.

In Southern California, of course, suburban decline is not necessarily a slow bleed. Recent aerospace and defense closures—like Hughes Missile Division’s abrupt departure from Pomona, or Lockheed’s abandonment of its huge Burbank complex—have had the social impact of unforeseen natural disasters. Following the Lockheed shutdown, for example, welfare caseloads in the eastern San Fernando Valley soared by 80,000 in a single eighteen-month period. In the Valley as a whole (population 1.2 million), one in six residents now lives below the poverty line, and 111,000 collected unemployment checks in 1995. Gang violence has relentlessly followed in the wake of the new immiseration, and the “most dangerous street in Los Angeles,” according to the LAPD, is not in South Central or East L.A., but is Blythe Street in the Valley, a few blocks from the corpse of a G.M. assembly plant shut down in 1993.

But older suburbs’ losses are usually someone else’s gain. Just as the inner-ring suburbs once stole jobs and tax revenues from central cities, so now their pockets are being picked by the new urban centers—further out on the spiral arms of the metropolitan galaxy—that Joel Garreau named “edge cities.” It has been estimated, for example, that the inner-ring suburbs of Minneapolis-St. Paul lost 40% of their jobs during the 1980s to the so-called Fertile Crescent of edge cities on the metro-region’s southwest flank. Schaumburg and central DuPage County—west of O’Hare International Airport—have had similar adverse impacts upon the older suburban communities of Cook County, as have the young edge cities of Contra Costa County upon east San Francisco Bay’s traditional blue-collar suburbs.

In Los Angeles County, the eighteen-mile-long, tapeworm-shaped City of Industry puts a bizarre spin on the idea of the Edge City. It won incorporation in 1958 through the gimmick of counting mental patients in a nearby asylum as permanent residents and has had the same mayor (answering to the same small elite) for nearly thirty years. Although tiny in population (just 680, including patients), it is a superpredator in economic terms, monopolizing most of the tax assets of the southern San Gabriel Valley, including 2,000 factories, warehouses, and discount outlets, as well as a world-class golf course and resort hotel. Its malign influence on surrounding, tax-starved, mainly Latino suburbs like La Puente and South El Monte (which play the role of its residential Bantustans) has been compared to an “economic atom bomb.”

The edge cities, moreover, have rapidly translated their rising economic power into decisive electoral clout. Consider the astonishingly homogeneous composition of the current Republican leadership in the House. Speaker Gingrich and his top dozen lieutenants (Archer, Armey, Crane, Hyde, Kasich, etc.) represent, without a single exception, the affluent, self-contained outer suburbs—Route 290 (Houston), Las Colinas (Dallas), Schaumburg (Chicago), DuPage (Chicago), suburban Columbus, etc.—that have been the big winners in the intrametropolitan distributional struggles of the last generation. Gingrich’s Revolution, in a profound sense, has been the Edge City Revolution.

This one-sided competition between old and new suburbs has exploded latent class divisions in the historic commuter belts. Southern California, in particular, has become an unstable mosaic of such polarizations. Think of the widening socioeconomic (and ethnic) divides between northern and southern Orange County, the upper and lower tiers of the San Gabriel Valley, the east and west sides of the San Fernando Valley, or the San Fernando Valley as a whole and its “suburbs-of-a-suburb” (like Simi Valley and Santa Clarita).

Landscape amenities help shape this new metropolitan hierarchy. As a rule of thumb, Los Angeles County’s affluent white suburbanites have retreated to choice foothill and beachfront communities, while the white working class has moved to new commuter ‘burbs on the edge of the desert in northern Los Angeles and western San Bernardino and Riverside counties. The older ‘burbs in the interior coastal plain have become majority Black, Latino, and Asian. As in the San Francisco Bay region, there is permanent cold war over tax revenue and allocation of public services between the poorer “flats” and the tonier “hills.”

In other metropolitan areas, of course, the class differentiation of suburbia still corresponds to the concentric rings—income increasing outward—of the old Burgess Park model of urban ecology. The “hole in the donut,” as it were, is growing larger. At the same time, the new intensity of intersuburban interaction—including commutes-to-work and flow of goods—has dramatically weakened, if not fully displaced, the traditional solar system model of suburbs radially attracted to the center. Indeed, in some metropolises, the outlying major airport, with its office towers, warehouses, and convention facilities, has become more gravitationally important as a center of employment and exchange than the older downtown.

The have-not suburbs, moreover, have accelerated their own decline by squandering scarce tax resources in zero-sum competitions for new investment. Too many poor communities have tried to upscale themselves through a combination of draconian social engineering (restriction or even removal of low-income residents) and desperate bids for new tax resources. If a decade ago, every aging L.A. suburb from Compton to Pomona had to have its own auto mall, now the mügic bullet is believed to be a card casino (and both Compton and Pomona are scheming to build one). Redevelopment programs, which in California devour 10 to 15% of local tax revenue, have become little more than cargo cults, praying for miraculous investments that never come.

In addition to the dramatic hemorrhage of jobs and capital over the last decade, senile suburbia also suffers from premature physical obsolescence—the architectural equivalent of Alzheimer’s disease. Much of what has been built in the postwar period (and continues to be built today) is throw-away architecture, with a thirty-year or less functional lifespan. “Dingbats” and other light-frame sunbelt apartment types are especially unsuited to support the intergenerational continuity of community and property. At best, this stucco junk was designed to be promptly recycled by perennially dynamic housing markets. But such markets have stagnated or died in much of the old suburban fringe.

Now millions of units of this disposable, ticky-tacky stuff are beginning to erode into the slum housing of year 2000. Again, our Ur-suburb, the San Fernando Valley, provides a telling example. The colossal $26 billion damage inflicted by the Northridge earthquake (only a “moderate” temblor on the Richter scale) exposed some of the submerged bulk of this building-quality crisis as residents were literally killed by shoddy construction. (Disaster costs do not include the 25% decline in single-family home values throughout the Valley since 1992: a family-economic catastrophe exacerbated by insurance companies refusal to provide new—legally required—earthquake coverage to homeowners.)

Although no one has yet attempted the calculation, there is little reason to suppose that this suburban “housing deficit”—the replacement cost of obsolete and unrestorable building stock—will be any smaller than Clinton’s once famous but now forgotten “infrastructure deficit.” Nor is it likely, as declining suburbs become the new pariahs, that the free market’s invisible hand will linger longer than it takes to draw a fatal red line around their prospects for housing reinvestment. The same grim calculations apply to the neglected social infrastructure—schools, parks, libraries, etc.—created in suburbia between the 1920s and 1960s.

All of this, of course, is especially bad news for poor, inner-city residents who are being urged by every pundit in the land to find their salvation in the suburbs. Indeed, confronted with virtually paleolithic conditions of life in collapsing city neighborhoods, hundreds of thousands of Blacks and Latinos are finally finding it possible to move into the subdivisions where Beaver Cleaver and Ricky Nelson used to live. The once monochromatic San Fernando Valley, for example, now has a slight non-Anglo majority (51 to 53%) of Latino, Black, Middle Eastern, and Asian residents, including more than 500,000 recent immigrants. There are more people of Mexican descent in Ozzie-and-Harriet Land than in East L.A.

But their experiences too often repeat the heartbreak and disillusionment of the original migrations to the central cities. What seemed from afar a promised land is, at closer sight, a low-rise version of the old ghetto or barrio. Like a maddening mirage, jobs and good schools are still a horizon away, in the new edge cities. The “good ole boy” regimes that hold power in the interregnum between white flight and the slow accession of new Black or Latino electoral majorities usually loot every last cent in the town treasury before making their ungraceful exits. As a result, minorities typically inherit municipal scorched earth—crushing redevelopment debts, demoralized workforces, neglected schools, ghostlike business districts, etc.—as their principal legacy from the ancient regime.

In the meantime, the stranded and forgotten white populations of these transitional communities are too easily tempted to confuse structural decay with the sudden presence of neighbors of color. The vampirish role of the edge cities in sucking resources from older, more central regions of the metropolis is less immediately visible than the desperate needs of growing populations dependent upon the dole. Political discourse, moreover, constantly valorizes resentment against the poor and people of color, while remaining discreetly silent about the real structure of urban inequality. In the absence of any serious vision of reform, one of the most worrisome prospects is that new-wave racism—even some viral mutation of fascism—may yet grow legs of steel in the ruins of the suburban dream.

Mike Davis is on the faculty of the Southern California Institute of Architecture; he is the author of City of Quartz and the forthcoming Ecology of Fear.