Still Here

Dolores Hayden, in her books Redefining the American Dream and The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, elaborates how conventional ideas of gender, class, and caste influence the critical evaluation of architectural achievement—a discussion extremely relevant to the careers of Julian Francis Abele, Hilyard Robinson, and Paul R. Williams. This trio of African Americans remains largely invisible within the history of architecture and architects in the United States, even as their work increasingly becomes known in the black community. Rectifying this invisibility would surely be consistent with the current and appropriate emphasis on our society’s “multicultural” character, if, by that term, we mean to encourage a fundamental reconceptualization of who we have been and are as a people. The potential benefits for architectural education of including the work of these three in “the canon” are significant. Whereas we are accustomed to inferring vision almost exclusively from aesthetics, their individual approaches to the practice of the social art of architecture also attest to vision. Each was highly skilled and rooted in the American experience, and each made an important mark on the built environment of the United States. A thoughtful assessment of their contributions, as unburdened as possible by the historical demons that sometimes obscure judgment, could spur thought and discussion toward a more serviceable set of standards for training future generations of architects, and for determining the quality of buildings.

Three Architects of Afro-America: Julian Francis Abele, Hilyard Robinson, and Paul R. Williams

Abele’s stylistic reserve contrasts with the turbulence about style going on within architecture concurrent with his career—challenges to classicism as the fount of inspiration for American civic architecture were many and persistent. American architects were searching for ways to manipulate the forms they had inherited from the Old World—a search exemplified, for instance, in Maybeck’s San Francisco Palace of Fine Arts (1915)5—to accommodate their New World experience and evolving culture. Moreover, Trumbauer’s embrace of a black protegé, despite opposition from within and outside the firm, implied that he, too, may have questioned, and been willing to flout, the norms of his day.

Why, then, was the work of Trumbauer’s office, given Abele’s central role in its creation, so lacking any spirit of rebellion, so clearly on the side of the conservatives in the debate about sources and references for American architectural expression? The answer, I propose, is a simple one. First, Trumbauer’s clients were almost exclusively Euro-American, leaders of the Eastern establishment who would not be likely to encourage their architects to diverge from the classical tradition. Second, in Abele’s era, most African Americans of his class aspired to the same kind of education—with all its accompanying Eurocentric values and standards—enjoyed by the white middle and upper classes. It was felt that highly educated black people were the key to community advancement, both practically and symbolically, through their rebuttal, by example, of stereotypes and prejudices. Success in the professions, then, was seen as closely tied to the embrace and mastery of prevailing norms, a view that would perhaps have been especially widespread with respect to such an elite discipline as architecture. The question, nonetheless, is one to keep in mind in considering the work of Hilyard Robinson and also of Paul R. Williams—the most famous black American architect.

Hilyard Robinson

In 1996, a made-for-TV movie chronicled the true-life exploits of the “The Tuskeegee Airmen,” African American fighter pilots who received segregated training in Alabama at an army base adjacent to Tuskeegee Institute, and who served with great distinction in the Second World War. As a child living at Tuskeegee and watching those young men swagger around the campus, I knew exactly what I wanted to be when I grew up—no matter that many in the military scoffed at the notion of black pilots.

Not only did one of the airmen, Dr. Roscoe Brown, become the first pilot of any color to shoot down a Luftwaffe jet, but, unknown to me at the time, the base where he and the others trained was designed by a black architect, Hilyard Robinson,6 and built by a black architectural and construction firm, McKissack & McKissack. (Most of Tuskeegee’s major buildings were also designed by black architects and built by students, in keeping with the philosophy of its founder, Booker T. Washington.)

Hilyard Robinson, of Washington, DC, though less known today than either Abele or Williams, is the architect among the three to whom I feel most sympathetic. When I visited his office as a young architect, he was generous with his time and discussed various issues of Modernism in a way that went to the heart of my interests and concerns. Captivated by both the person and the work, I especially appreciated the intimate scale and dynamic proportions of his residential buildings.

The Langston Terrace Dwellings, Robinson’s best-known design, built in 1936, “was accorded a much-deserved listing on the National Register of Historic Places”7 in 1987 and was the subject of a 1988 television documentary. Langston Terrace, like the Harlem River Houses that John Louis Wilson, et al., created at about the same time, was favorably reviewed by Lewis Mumford in The New Yorker.8 Not surprisingly, the complex reminded Mumford and others of modern European housing. After serving in the First World War, Robinson had returned to Europe to study the work of the Bauhaus and the Dutch Modernists. During that time, from 1931 to 1933, he also traveled in Russia.9 He, like Abele, studied at the University of Pennsylvania but received his bachelor’s degree (1925) and master of architecture (1931) from Columbia University.

Langston Terrace arose out of the movement to provide not only safe and sanitary housing for working-class and poor people, but also housing that would uplift the spirits of its residents. Initiated before public housing entered its punitive phase of withheld amenities, Langston incorporated well-designed open spaces, sensitively scaled details, and artwork of the “social realism” school then common to Europe and Latin America that depicted working-class subjects in heroic poses. The architecture asserts Modernism’s faith in the capacity of buildings to enhance human experience. The same methods employed by European and Euro-American architects of similar faith are found in Langston: industrial sash windows, sleek curved railings, an openly expressed power plant, an urban plan. Communal interdependence is expressed through the relation of the open space and buildings to the sloping site.

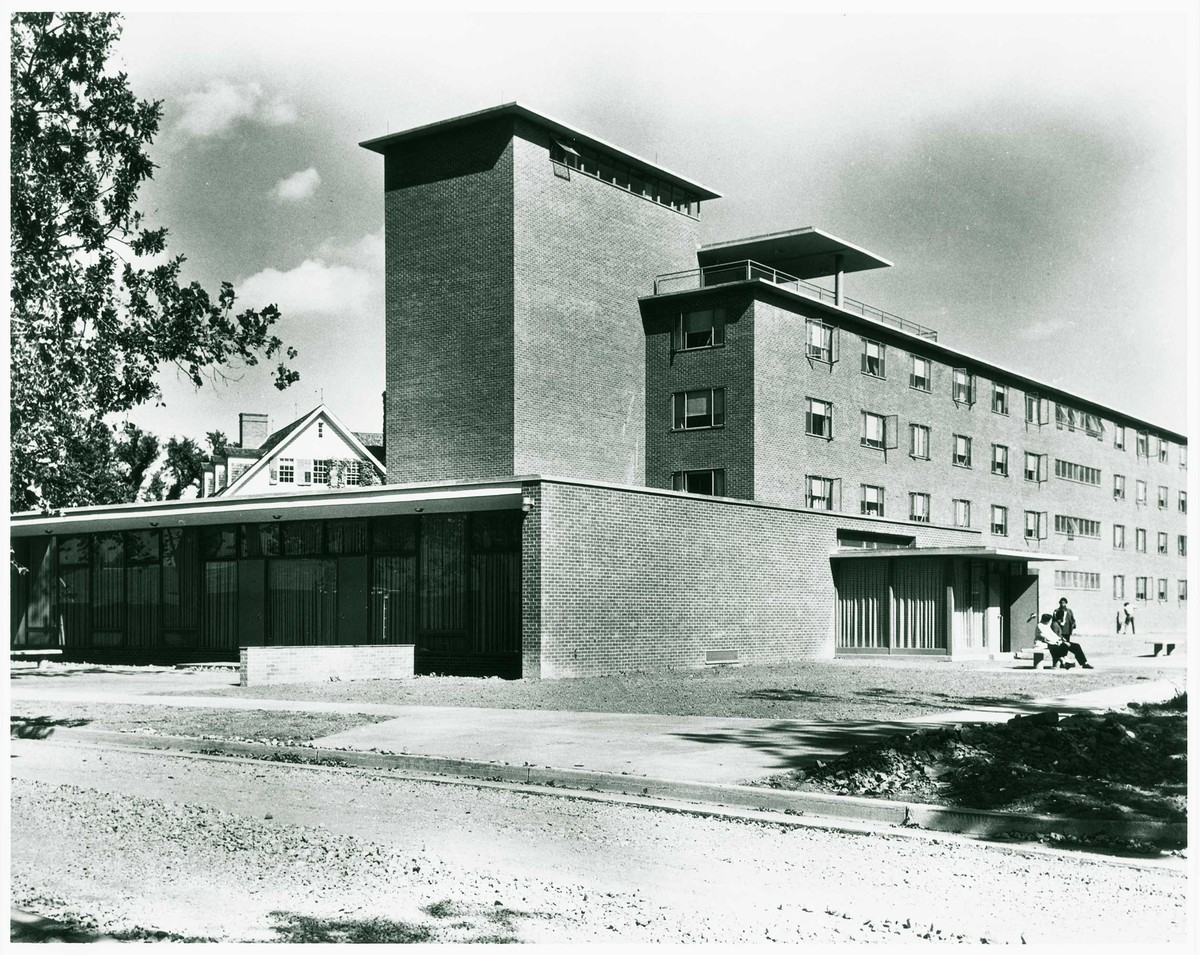

Technology intrigued Robinson throughout his life. In 1937, he designed and patented award-winning, and at the time “high-tech,” desk and floor lamps for the Cook Hall dormitories at Howard University. His Fine Arts complex at Howard and the Communications Building at Hampton Institute (1960) are sophisticated in their provision of the latest technology for speech instruction, theater, and broadcasting. His combination of strong massing alleviated by a sense of lightness and wit places Robinson’s design sensibility somewhere between that of Abele and Williams. But more than either of those colleagues, he engaged the dialogue between European internationalism and American Modernism—a compelling feature, in light of today’s standards and perspectives. Through his preoccupations and work, Robinson demonstrated a strong commitment to serving and celebrating Afro-America without harboring any sense that such a commitment conflicted with his other, outreaching impulse to assimilate the architectural languages of his time and the broad cultural imperatives of a shared American identity.

Where Julian Francis Abele stuck to classicism and “was prepared,” according to his descendant Peter Cook, “to design a classical mansion even if the client only wanted a little bungalow,”10 the ongoing concern in Hilyard Robinson’s work was his perception of, and commentary on, the relationships among architecture, function, and contemporary culture.

Paul R. Williams

In the architecture of Paul R. Williams,11 one confronts work that is less about stylistic consistency than about a direct response to the aspirations of his clients, to socioeconomic developments in Southern California in the first half of the century, and to Southern Californians’ self-conscious understandings of style and urbanity.

Important to a consideration of his work is some reference to its mid-20th-century context. In those years California’s economy was growing rapidly, its population and lifestyles undergoing dramatic change and diversification. In the wake of the Great Depression, and subsequently of the Second World War, multiethnic blue collar workers flocked to the state in great numbers, as did white collar aspirants attracted to the movie factories and a slew of new industries. Each immigrant group sought an identity that reflected its new, improved circumstances.

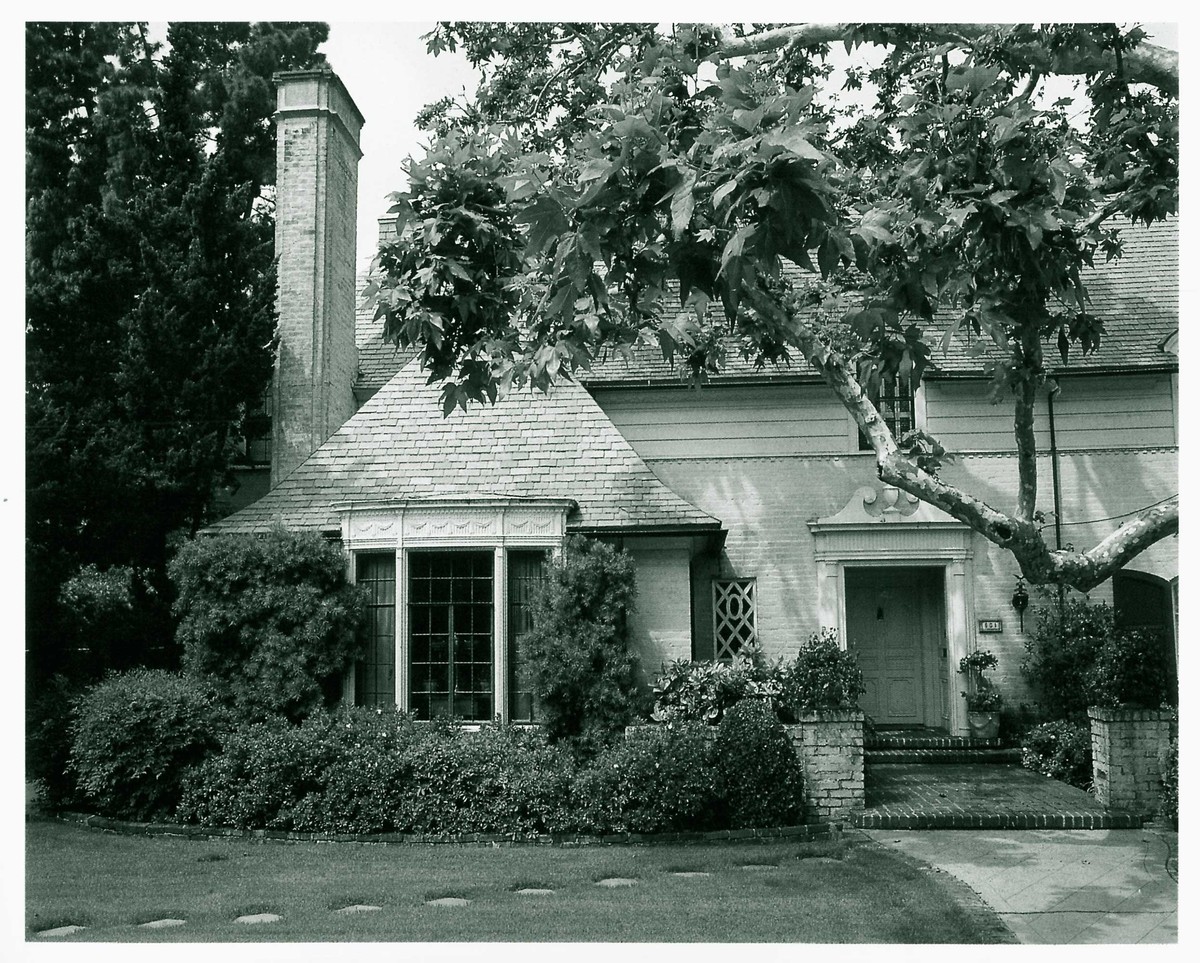

Fittingly, Williams first received notice for his successful entries in small home competitions, his premiated schemes earning him a reputation in a design realm that was very important in Southern California and throughout the West at the time. A tremendous market for economical working- and middle-class dwellings had emerged, and throughout his career Williams was interested in this category of design, publishing two small-house pattern books.12

Meanwhile, the newly rich were building houses to display their sophistication, and here Williams shone. With his talent for what architect Jeh Johnson13 calls “creative eclecticism,” Williams was able—somewhat like Morris Lapidus—to concoct stylish pastiches. Each of his houses sported something extra, some identifying signature element created especially for its owner. It might be an entrance, a staircase, a garden, a diversion in scale, or a unique flow of space. Generally, Williams’s designs were much like the man himself: affable, well-mannered, gracious and graceful, a mite “different” but not so different as to shock. Like the movies, his work helped define a California style of self-assured, easy worldliness. Like the master politician whose finger is always on the pulse of his constituency, Williams appeared to lead while actually giving form and substance to the vaguely articulated dreams of his clients. And, of course, the imagery in his work changed as the self-images of Californians evolved.

My first assignment, as an architect in the office of “P.R.,” was a house for Frank Sinatra. Jeh Johnson and I had driven from the east coast to Los Angeles in June 1957, feeling lucky to have gotten summer jobs on the strength of letters from school. Immediately upon our arrival, coworkers regaled us with office lore and tales of Williams’s fabulous skills in drawing and handling clients. (I was put to work on the tile floor in Mr. Sinatra’s kitchen, and on the bar. Jeh was assigned a stair railing.) The most prolific African American architect to date, Williams designed houses for a substantial client list that included Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Lon Chaney, Tyrone Power, Martin Landau, William “Bojangles” Robinson,14 and other movie stars, as well as Jay Paley, William Paley, and Walter Winchell. His 1931 house for E.L. Cord, manufacturer of Cord automobiles, marked a new plateau in his already solid practice and further enhanced his prominence among California architects.

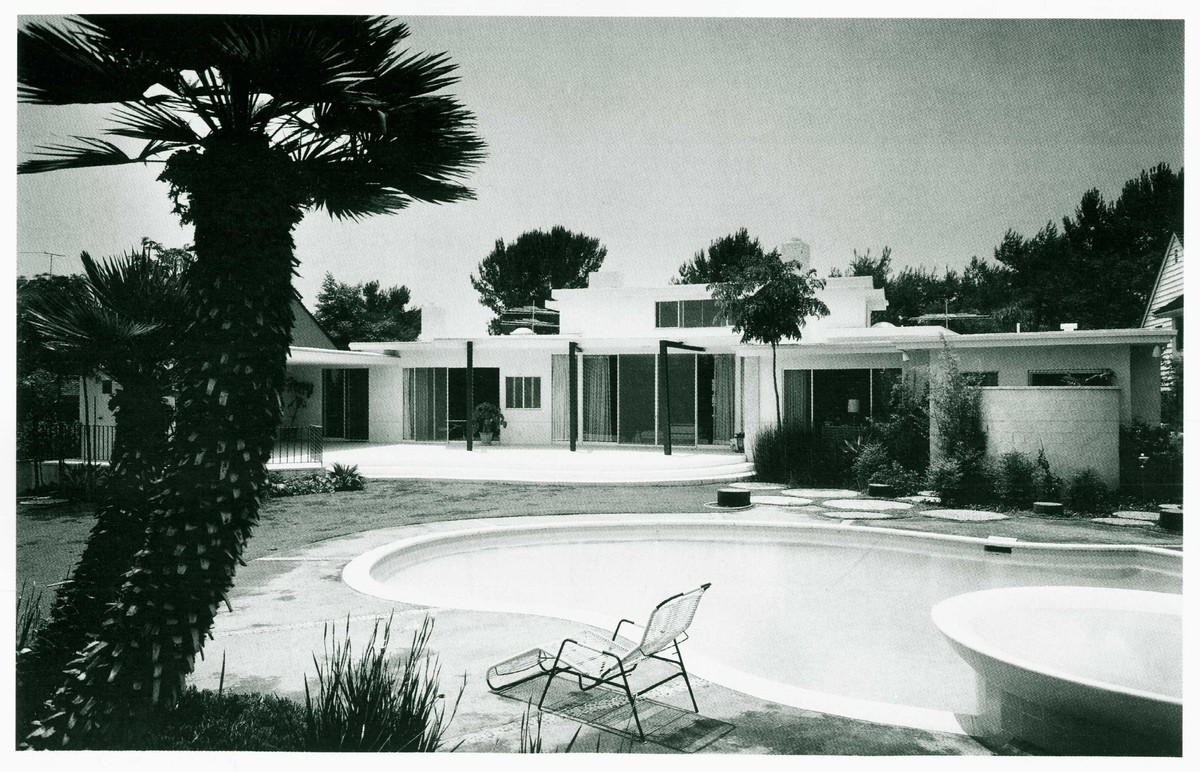

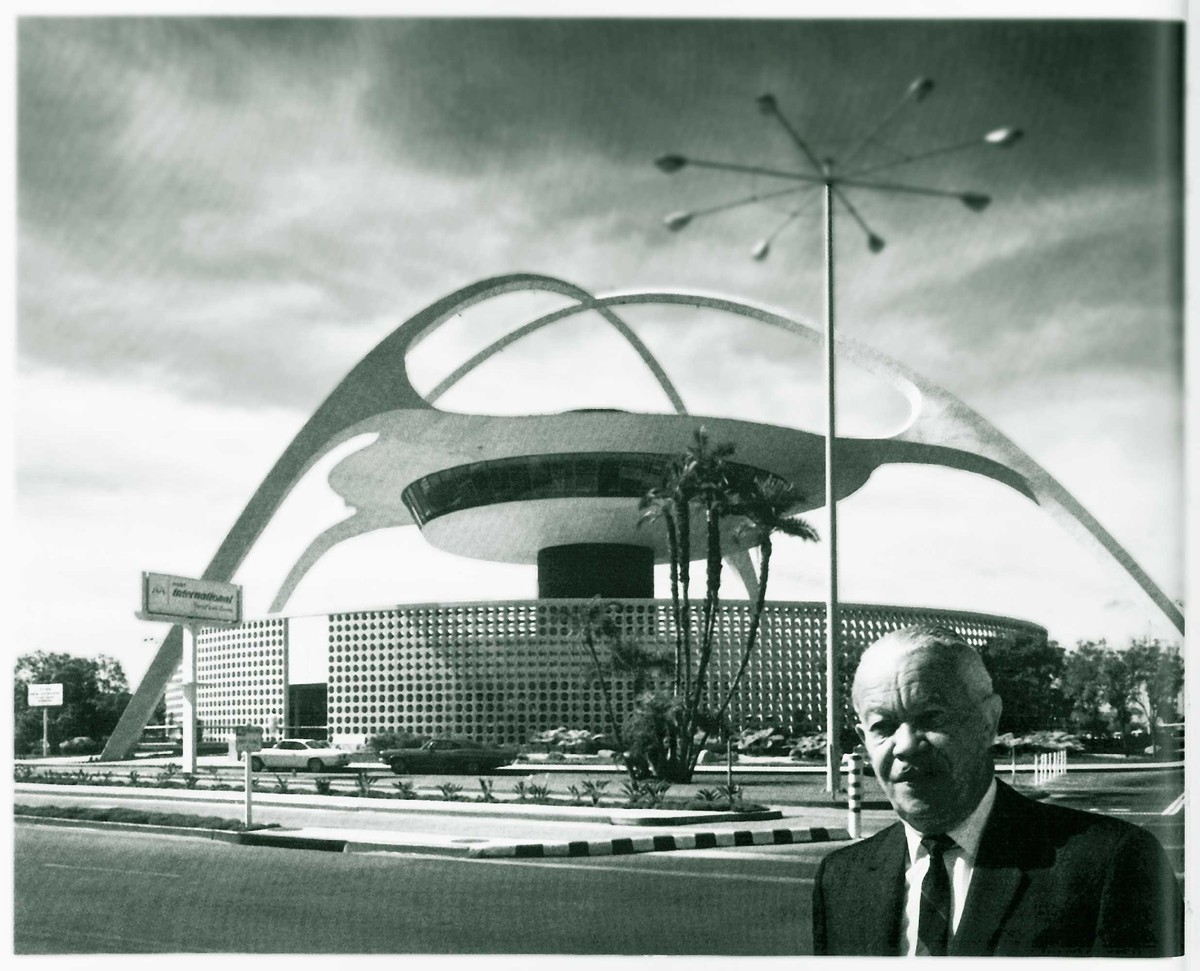

Later in his career, Williams secured several commercial projects (matching Abele’s experience at Duke, Williams was not privileged to visit the addition to the Beverly Hills Hotel that he designed), along with some civic commissions that included a school in Harlem, New York City (1960), and a Los Angeles County Courthouse.15 One particularly high-profile project was the Theme Building for Los Angeles International Airport. However, I find his enormous talent to be less represented in these commissions, whose clients were more distant and whose programs were unrelated to individual lifestyle, than in the houses, which reflect his knack for heeding client needs and aspirations. Moreover, the houses exhibit Williams’s expert expression of the strong relationships between interior and exterior spaces, relationships warranted by the climate. Siting was an important element in his work, as exemplified in the Ball/Arnaz house—which is low in the desert, reminiscent of Neutra, but less assertive stylistically. Similarly, spaces in another of William’s houses, the Kelton house, interact smoothly with exterior views and landscape. The nonresidential buildings are less site-specific and distinctive, suggesting that, like other California architects, Williams worked most comfortably in low-density settings where the site can surround the structure, as opposed to cityscapes where buildings define the open space.

Though Williams’s style varied over time, his consistency and skill endured: plans are well organized, proportions are harmonious, designs are internally coherent, and details correlate with themes. At the same time, it is noteworthy that, compared to the output of some of his near contemporaries, highlighted in Esther McCoy’s Five California Architects, Williams did not “push the aesthetic envelope.” Cutting-edge he was not. Williams felt that those among his contemporaries whom critics deemed “aesthetically rigorous,” such as Frank Lloyd Wright, unfairly imposed their formal concerns on their clients. In any case, Williams’s presumably less-than-adventurous impulses both recall the question raised earlier in this article and raise some important new ones.

Could a black architect in Williams’s circumstances have worked outside, rather than skillfully within, the well-understood aesthetic limits of his day and have still attracted clients? Moreover, is our pervasive tendency to judge buildings purely on aesthetic grounds perhaps too narrow? Did Modernism err in proclaiming itself the one true style, “the International Style” no less, and in fostering a type of architectural criticism that often denies context, that fails to acknowledge place as a critical factor in the evaluation of buildings? Do we architects really want to be—does society need us to be—“high priests” of pure design? Should the people who will inhabit the spaces we create have a better recognized and more authoritative role in the design process than is currently assumed to be acceptable?

The segmentation of architectural expression into high and low realms, and the designation of a small group of architects as the aesthetic elite of the profession, account, in part, for the relative obscurity of Abele, Robinson, and Williams, who, color aside, do not fit the mythic masterbuilder mold. Abele was apparently a quiet, self-effacing man absorbed in his work, whose own designs were credited to the name of another man. Robinson, pursuing a career that was closely tied to the black community, would most likely be viewed today as a socially responsible type who left an impressive body of work that expressed its creator’s effort to balance aesthetic and other concerns. Williams placed his enormous talents in service to the dreams of his clients, affluent and otherwise, creating architectural mirrors of the dynamic self-invention and popular cultural explosion taking place in his milieu. In the process, he made a significant contribution to the built world of Southern California. Men very much of the American times in which they lived, all were successful in their efforts to assimilate and synthesize, in architectural language, the myriad and complex elements of the world around them.

Julian Francis Abele

In a famous scene in the movie Rocky, the newly confident pugilist, standard-bearer of America’s ethnic working class, charges up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and vows to beat an opponent of African descent, whose loudmouth arrogance presumably symbolizes the not-to-be-denied aspirations of an insurgent caste. The irony of the filmmakers’ choice of the museum’s imposing Grecian architecture as the frame for their great white hope’s inspirational moment would not have been lost on Julian Francis Abele, the African American architect and painter who designed the museum.

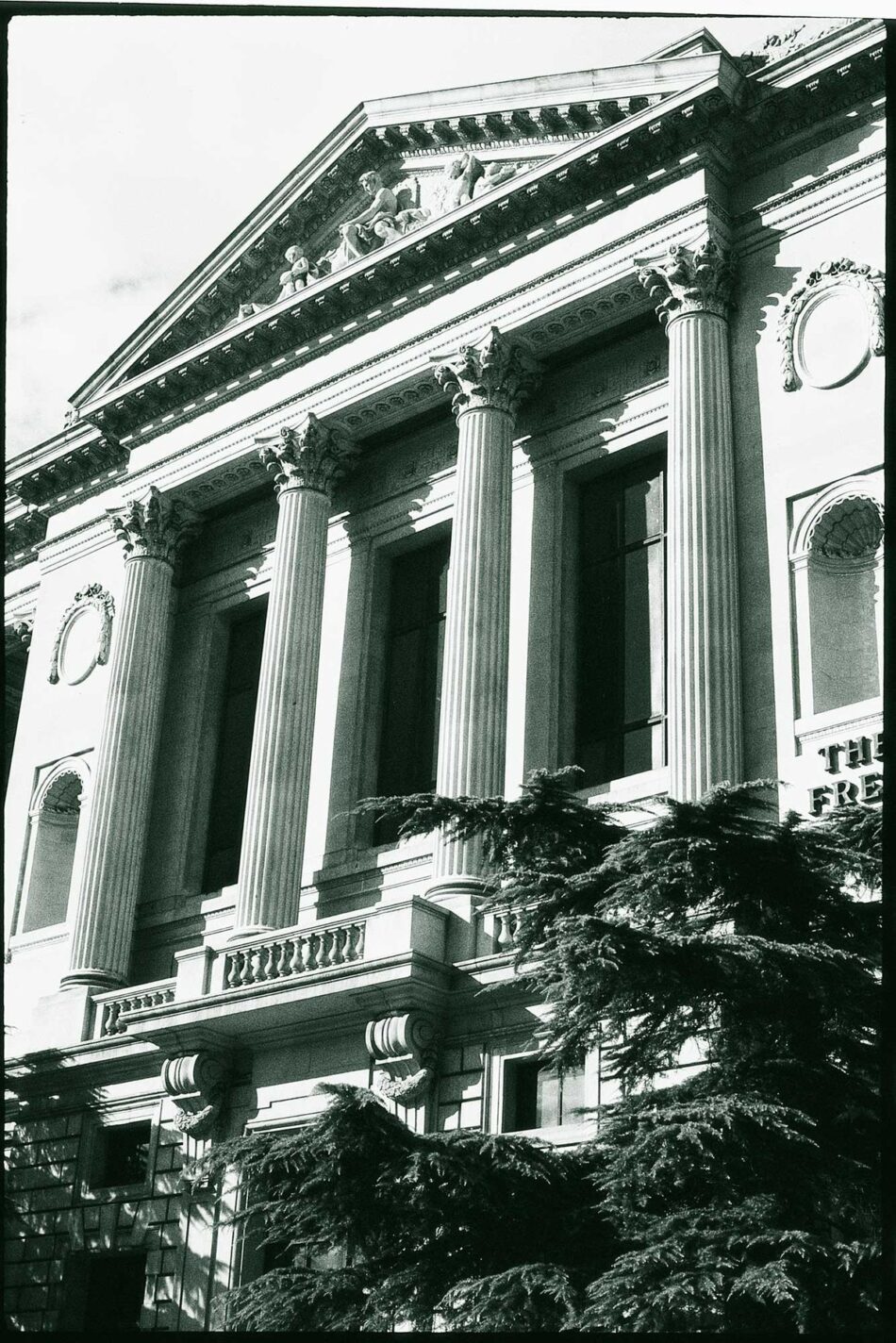

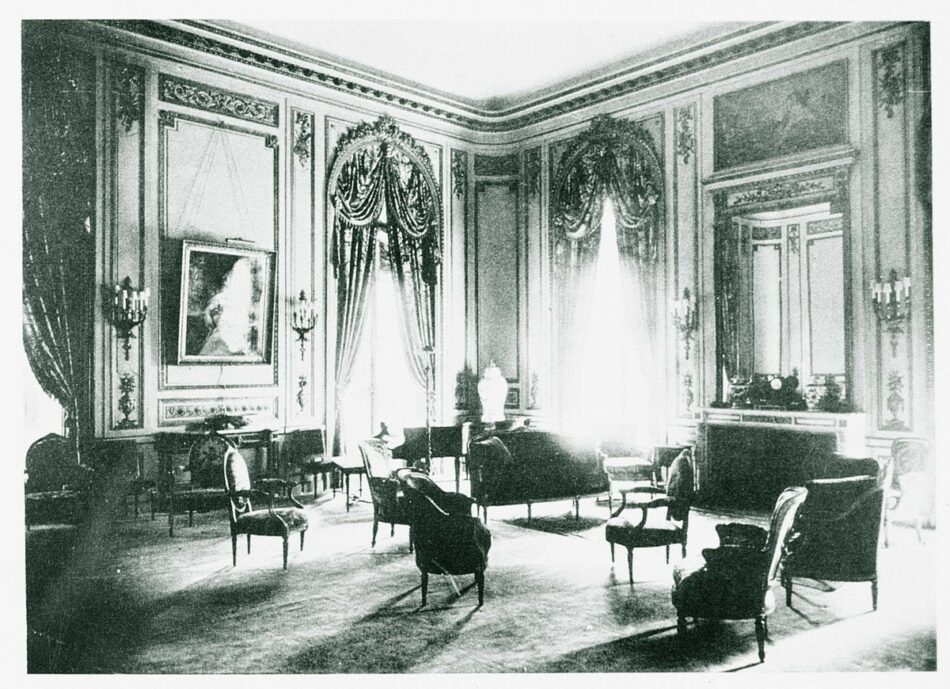

Abele’s career, beginning with his service as chief designer for the firm of Horace Trumbauer from 1909 until its dissolution1 in 1938, was full of such contradictions. In the Trumbauer office, Abele was architect for several buildings at Duke University in North Carolina, from which, of course, “Negroes” were then barred. Teamed with Trumbauer’s technical man, William Frank,2 he designed residences for many prominent Philadelphians. His projects include the Free Library of Philadelphia (1927), the Duke townhouse in New York City (1909)—now New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts—and Harvard’s Widener library (1913).3 These accomplishments, which reflect Abele’s immersion in classical themes, testify to the significance of the legacy bequeathed by the man described in Philly Talk as a “Forgotten Black Designer.”4

In 1902, Abele became the first African American to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania School of Architecture, and afterward from the École des Beaux Arts in Paris, his sojourn abroad having been underwritten by Trumbauer. He studied Greek and French Classical styles, drawing upon those traditions in his approach to both architecture and painting. Abele composed his structures carefully, gave them graceful proportions and a scale commensurate with their civic importance, and selected their materials meticulously. He was particularly concerned with the color of stone, to the point of attempting an evocation of Greek stone work. Though modest by temperament, Abele rendered powerful buildings of unrelieved seriousness that, to my mind, display little ambiguity or sensuality. Another characteristic of Abele’s designs, when contemplated through the lens of today’s multicultural sensitivities, is that on the surface they give no sense of the tension between his allegiance to European classicism and his own African American heritage. The one possible clue to such tension—which was inevitably present—was very subtle: his belief that the plan of a building determines how that building is experienced, a surprising view in one so wedded to the mantra of formal composition. Otherwise, neither in form, reference, detail, nor decoration do his buildings betray that the man who designed them was black.

The title of this essay refers to the dance composition “Still Here” by Bill T. Jones.

1 Wilson Dreck, “Julian Francis Abele,” unpublished article, 3. 2 Article in Philly Talk, unsigned, 1970, 27. 3 Dilys Winegrad, Eisenlohr: The President’s House, University of Pennsylvania (University of Pennsylvania Archives, 1984). 4 Op.cit. 5 Esther McCoy, Five California Architects (New York: Praeger, 1975), 36–41. 6 Richard K. Dozier, “The Black Architectural Experience in America,” in African American Architects in Current Practice, ed. Jack Travis (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1991). 7 Benjamin Forgey, “Cityscape,”Washington Post, June 4, 1988. 8 J. Leon Langhorne, unpublished paper in the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University. 9 Hilyard R. Robinson, curriculum vitae, undated but probably from the 1970s, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. 10 Peter Cook, AIA, an associate of Davis Brody Bond, is the grandson of Julian Abele Cook — Julian Francis Abele’s nephew — and also a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania School of Architecture. 11 Teleconference, March 1997, with Harold Williams, who worked for Paul R. Williams for more than ten years and refers to him as P.R. 12 Williams, curriculum vitae. 13 Jeh V. Johnson, a graduate of Columbia University, practices in Poughkeepsie, New York, and teaches at Vassar College. 14 Karen E. Hudson, Paul R. Williams: A Legacy of Style (New York: Rizzoli International, 1993), 230–235. Jeh V. Johnson and Harold Williams teleconferences, March 1997. 15 As part of our training that summer, I represented the office at the courthouse construction site for several weeks. Since the people in the office knew how little I, as a GSD student, knew about construction, my instructions were to say, whenever questioned about a building assembly, that I had to check the drawings or the specs. I was then to rush back to the site trailer, get the project architect on the phone, and try to explain the question. All of that so I would not embarrass myself or Williams’s staff. Needless to say, I probably did both.Max Bond, who graduated from the GSD in 1958, is a partner of Davis Brody Bond in New York City. He wishes to thank Jeh V. Johnson for his helpful comments on a draft of this article and Karen Hudson and Harold Williams for other assistance.