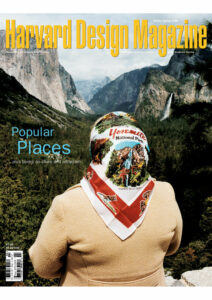

Beyond Wilderness and Lawn

The romance of wilderness is a quintessential American sentiment, but it is one indulged primarily in books or on vacation. The rest of the time, we tend to act in accordance with a very different idea of nature: the idea that the land is ours to dominate, whether in the name of God, during the nation’s early days, or later, in the name of Progress. It is astonishing that one culture could give birth to two such antagonistic strains—to both the worship of wilderness and the worship of progress, which usually entails the domination of wilderness. This latter notion, more manifest in the actual landscape than in our writings about it, has been as deleterious to the making of good gardens as has been the wilderness idea. It is far more likely to give us parking lots and shopping centers . . . and lawns.

Lawn

Anyone who has ever mowed a lawn can appreciate the undeniable pleasure of bringing a heedless landscape under control, however temporarily. But this is not, except perhaps in America, the same thing as gardening. For when we read that gardening is “the number one leisure activity” in this country, we need to remember that the statistics accommodate all those people for whom “gardening” consists exclusively of the pushing, or often driving, of an internal combustion engine over a monoculture of imported grass species.

The ideology of lawns cannot be reduced to the drive to dominate nature, though certainly that is one element of it. The love of closely cropped grass may well be universal, as Thorstein Veblen speculated in The Theory of the Leisure Class3; it is a reminder of our pastoral roots, and perhaps also of our evolutionary origins on the grassy savannas of East Africa. America’s unique contribution to humankind’s ancient love of grass has been, specifically, the large, unfenced patches of lawn in front of our houses—the decidedly odd custom, to quote one authority, “of uniting the front lawns of however many houses there may be on both sides of a street to present an untroubled aspect of expansive green to the passerby.”4 This definition was set forth by the historian Ann Leighton, who concluded after a career spent studying the history of American gardens that the front lawn was our principal contribution to world garden design. How depressing.

The same rapid post-Civil War growth that made wilderness preservation seem imperative also gave us the institution of the front lawn, the birth of which, as near as I can determine, should be dated on or about 1870. At that time several developments—some social and economic, others technological—combined to make the spread of front lawns possible.

First was the movement to the suburbs, then called “borderlands.” Before 1870, anyone who lived beyond the city was a farmer, and the yards of farmers were strictly utilitarian. According to the accounts of many visitors from abroad, yards in America prior to 1870 were, to put it bluntly, a mess. The belief that the American landscape has declined and fallen from some pre-industrial pastoral ideal is, in fact, false; the 19th-century rural homestead was a ramshackle affair. Americans rarely gardened, at least ornamentally. The writer William Cobbett, visiting from England, was astonished by the “out-of-door slovenliness” of these homesteads. Each farmer, he wrote, “was content with his shell of boards, while all around him is as barren as the sea beach . . . [even] though there is no English shrub, or flower, which will not grow and flourish here.”5

All that begins to change with the migration to the borderlands. For the first time urban, cosmopolitan people were choosing to live outside of town and to commute, by way of the commuter railroad system then being built. Their homes, also for the first time, are homes in the modern sense: centers of family life from which commerce—and agriculture—have been excluded. These homes are refuges from urban life, which by the late 19th century was acquiring a reputation for danger and immorality. The rapidly expanding middle class was coming to believe that a freestanding house surrounded by a patch of land, allowing you to keep one foot in the city and the other in the countryside, was the best way to live.

But how should this new class of suburbanites organize their yards? No useful precedents were at hand. So, as often happens when a new class of affluent consumers in need of guidance arose, a class of confident experts arose as well, proffering timely advice. A generation of talented landscape designers and reformers came forward, from midcentury on, to advise the middle class in its formative landscaping decisions. Most prominent were Frederick Law Olmsted, his partner Calvert Vaux (a transplanted Englishman), Andrew Jackson Downing, and Frank J. Scott, a disciple of Downing’s who would prove to be the American lawn’s most brilliant propagandist.

These men were seeking the proper model for the new American suburban landscape. Although they were eventually to develop a distinctly American approach, they began, typically, by looking to England—specifically to the English picturesque garden which, of course, featured gorgeous lawns, the kind that only the English seem able to grow.

Clearly, Americans did not invent lawns per se; they’d been popular in England for centuries. But in England lawns were found mainly on estates. The Americans set out to democratize them, cutting the vast, manorial greenswards into quarter-acre slices everyone could afford. (Olmsted’s 1868 plan for Riverside, outside Chicago, is a classic example of how the style of an English landscape park could be adapted to an American subdivision.)

The rise of the classic American front lawn awaited three developments, all of which were in place by the early 1870s: the availability of an affordable lawnmower, the invention of barbed wire (to keep animals out of the front yard), and the persuasiveness of an effective propagandist. In 1832 a carpet manufacturer in England named Edwin Budding invented the lawnmower; by 1860 American inventors had perfected it, devising a lightweight mower an individual could manage; and by 1880 this machine was relatively inexpensive. Before the invention in Peoria, Illinois, of barbed wire in 1872, the fencing of livestock was a dubious proposition, and the likelihood was great that one’s beautiful front lawn would be trampled by a herd of livestock on the lam. But soon after the mass-marketing of barbed wire, municipal ordinances were being passed penalizing anyone who let livestock wander freely through town.

As for the effective propagandist, the man who did most to advance the cause of the American front lawn—and thus to retard the development of the American garden—was Frank J. Scott, who wrote a best-selling book called The Art of Beautifying Suburban Home Grounds. Published in 1870, the book is an ecstatic paean to the beauty and indispensability of the front lawn. “A smooth, closely shaven surface of grass is by far the most essential element of beauty on the grounds of a suburban house,” Scott wrote.6 Unlike the English, who viewed lawns not as ends in themselves but as backdrops for trees and flower beds, and as settings for lawn games, Scott subordinated all other elements of the landscape to the lawn. Shrubs should be planted right up against the house so as not to distract from, or obstruct the view of, the lawn (it was Scott who thereby ignited the very peculiar American passion for foundation planting); flowers were permissible, but they must be restricted to the periphery of the grass. “Let your lawn be your home’s velvet robe,” he wrote, “and your flowers its not-too-promiscuous decoration.”7 It’s clear that his ideas about lawns owe much to puritan attitudes that regarded pure decoration, and ornamental gardening, as morally suspect. Lawns fit well with the old American preference for a plain style.

Scott’s most radical departure from old-world practice was to insist upon the individual property owner’s responsibility to his neighbors. “It is unchristian,” he declared, “to hedge from the sight of others the beauties of nature which it has been our good fortune to create or secure.”8 He railed against fences, which he regarded as selfish and undemocratic—one’s lawn should contribute to the collective landscape. Scott elevated an unassuming patch of turf grass into an institution of democracy. The American lawn becomes an egalitarian conceit, implying that there is no need, in Scott’s words, “to hedge a lovely garden against the longing eyes of the outside world” because we all occupy the same (middle) class.9

The problem here, in my view, is not with the aspirations behind the front lawn. In theory at least, the front lawn is an admirable institution, a noble expression of our sense of community and equality. With our open-faced front lawns, we declare our like-mindedness to our neighbors. And, in fact, lawns are one of the minor institutions of our democracy, symbolizing as they do the common landscape that forms the nation. Since there can be no fences breaking up this common landscape, maintenance of the lawn becomes nothing less than a civic obligation. (Indeed, the failure to maintain one’s portion of the national lawn—for that is what it is—is in many communities punishable by fine.) Our lawns exist to unite us. It makes sense, too, that in a country whose people are unified by no single race or ethnic background or religion, the land itself—our one great common denominator—should emerge as a crucial vehicle of consensus. And so across a continent of almost unimaginable geographic variety, from the glacial terrain of Maine to the desert of Southern California, we have rolled out a single emerald carpet of lawn.

A noble project, perhaps, but one ultimately at cross purposes with the idea of a garden. Indeed, the custom of the front lawn has done even more than the wilderness ideal to retard the development of gardening in America. For one thing, we have little trouble ignoring the wilderness ideal whenever it suits us; ignoring the convention of the front lawn is much harder, as anyone who has ever neglected mowing for a few weeks well knows. In fact it’s doubtful that the promise of the American garden will be realized as long as the lawn continues to rule our yards and minds.

It’s important to note that it is not grass per se that is inimical to gardens; indeed, some patch of lawn is essential to many kinds of gardens—the English landscape garden is unimaginable without its great passages of lawn. The problem is specifically the unfenced front lawns, and that problem has both a practical and theoretical dimension.

In practical terms, by ceding our front yards to lawn, we relinquish most of the acreage available to our gardens. Indeed, this space has effectively been condemned by eminent domain, handed over to the community. In fact, when asked, most people will say they regard their front lawns as belonging to the community, while their backyards belong exclusively to themselves.

Because front-lawn convention calls for the elimination of fences, we have rendered all this land unfit for anything but exhibition. Our front yards are simply too public a place to spend time in. Americans rarely venture into their front yards except to maintain them. As one American landscape designer noted, in the 1920s, our lawns are designed for “the admiration of the street.”10 But consider how novel an idea this is: throughout history gardens have usually been thought of as enclosed places—this concept is embedded in the word’s etymology. And while great unenclosed gardens (such as Versailles, and the English landscape gardens) have been created, these have invariably been so vast in scale that privacy was not an issue. Our lawns might descend from the English picturesque tradition, in which the making of unimpeded views took precedence over the creating of habitable space, but on the scale of suburban development, a “prospect” is not possible without destroying the possibility of usable individual spaces—and of meaningful gardens.

From a philosophical point of view, the very idea of lawns does violence to the fundamental principle of gardening, as expressed by Alexander Pope: “Consult the genius of the place in all.” The lawn is imposed on the American landscape with no regard for local geography or climate or history. No true gardener, consulting the genius of the Nevada landscape, or the Florida landscape, or the North Dakota landscape, would ever propose putting a lawn in any of these places; and yet lawns are found in all of these places. If gardening requires give-and-take between the gardener and a piece of land, then putting in a lawn represents instead a process of conquest and obliteration, an imposition—except in a very few places—of an alien idea and even, as it happens, of a set of alien species (for none of the grasses in our lawns are native to this continent).

And last, the culture of the lawn discourages the very habits of mind required to make good gardens. Besides a sensitivity to site and willingness to compromise with nature, the gardener, to accomplish anything powerful, must be able to approach the land not as a vehicle of social consensus (which by its very nature will discourage innovation) but as an arena for self-expression.

For all these reasons, it will probably take a declaration of independence from the American lawn before we can expect the American garden to flourish.

The front lawn and the wilderness ideal still divide and rule the American landscape, and will not be easily overthrown. But American attitudes toward nature are changing, and, viewed from one perspective at least, this leaves room for hope. One of the few things we can say with certainty about the next five hundred years of American landscape history is that they will be shaped by a much more acute environmental consciousness—by a pressing awareness that the natural world is in serious trouble, and that serious actions are needed to save it. So how will the American garden fare in an age dominated by such an awareness? What about the wilderness ideal? And the front lawn?

It might seem axiomatic that, the greater the concern for the environment, the greater the regard for wilderness. But it is becoming clear that attention to wilderness no longer constitutes a sufficient response to the crisis of the environment. True, there are radical environmental groups, like Earth First!, which believe that salvation lies in redrawing the borders between nature and culture—in blowing up dams and powerlines so that the wilderness might reclaim the land. But an environmentalism dominated by love of wilderness dates to the era of John Muir, and while it has done much to protect a now-sacred eight percent of American land, it has offered little guidance as to how to manage wisely the remaining ninety-two percent, where most of us spend most of our time.

We must continue to defend wilderness, but adding more land to the wilderness will not solve our most important environmental problems. But even more important, nor will an environmental ethic based on the ideal of wilderness—which is, in fact, the only one we’ve ever had in this country. About any particular piece of land, the wilderness ethic says: leave it alone. Do nothing. Nature knows best. But this ethic says nothing about all those places we cannot help but alter, all those places that cannot simply be “given back to nature,” which today are most places. It is too late in the day to follow Thoreau back into the woods. There are too many of us, and not nearly enough woods.

But if salvation does not lie in wilderness, nor is it offered by the aesthetic of the lawn; in fact, the lawn, as both landscape practice and a metaphor for a whole approach to nature, may be insupportable in a time of environmental crisis. Remarkably, the lawn has emerged as an environmental issue in the last few years. More and more Americans are asking whether the price of a perfect lawn—in terms of pesticides, water, and energy—can any longer be justified. The American lawn may well not survive a long period of environmental activism—and no other single development would be more beneficial for the American garden. For as soon as an American decides to rip out a lawn, he or she becomes, perforce, a gardener, someone who must ask the gardener’s questions: What is right for this place? What do I want here? How might I go about creating a pleasing outdoor space on this site? How can I make use of nature here without abusing it?

The answers to these questions will be as different as the people posing them, and the places where they are posed. For as soon as people start to think like gardeners, they begin to devise individual and local answers. In all likelihood, post-lawn America would not have a single national style; we are too heterogeneous a people, and our geography and climate too various, to support a single national style. And that, after all, has been the lesson of the American lawn: imposing the same front yard in Tampa and Bethesda and Reno and Albany exacts too steep an environmental price. Undoubtedly lawns will survive in some places (such as the cool, damp Northwest, where the “genius” of the place may well accommodate them) but the American front yard will someday be entirely different things in Sausalito and White Plains and Fort Worth. Those who are intent on establishing a “New American Garden” may judge this a loss, and balk at giving up the idea of a single national landscape style. But as valuable as unifying national institutions may be, nature is a poor place to try to establish them. However one may judge multiculturalism, multi-horticulturalism is an environmental necessity. The New American Garden must be plural.

But even if an age of environmentalism doesn’t attack the lawn head on, it would still bode well for the garden in America. The decline of the lawn may be gradual and piecemeal and even inadvertent, as gardens gradually expand into the territory of the lawn, one square foot at a time. To put this another way: to think environmentally is to find reasons to garden. Growing one’s food is the best way to assure its purity. Composting, which should be numbered among the acts of gardening, is an excellent way to lighten a household’s burden on the local landfill. And gardens can reduce our dependence on distant sources not only of food, but also of energy, technology, and even entertainment. If Americans still require a moral and utilitarian rationale to put hoe to ground, the next several years are certain to supply plenty of unassailable, even righteous ones.

So I am optimistic about the American garden—or at least about the proliferation of gardens in America. As the environment take its necessary and inevitable place in our attention, the reasons to garden will become increasingly compelling, and the reason to maintain lawns correspondingly less so. Whether there will be a flowering of great gardens in America is another question, but here too there is a reason to be optimistic, one that may seem at first entirely off the point: almost overnight, Americans have invented a distinctive and accomplished cuisine.

Only a few years ago American cooking was no better than provincial Britain’s or Germany’s: unimaginative, heavy, relentlessly utilitarian. (Talk about the plain style!) Our recent culinary revolution suggests that a corner of the culture formerly neglected or disdained may suddenly become the focus and beneficiary of the kind of sustained attention and cultural support that makes genuine, original achievement possible. To take this analogy even further, my guess is that the same radical cosmopolitanism that today distinguishes American cuisine—its willingness to draw from a dozen different national traditions, combining them in never-before-seen combinations—will someday define the New American Garden.

If this analogy seems far-fetched—the lawn giving way to the mixed border the way the meatloaf has given way to the shiitake mushroom and goat cheese pizza—consider for a moment that the preconditions for a brilliant cuisine and a brilliant garden are so similar: both require the artful intermingling of nature and culture. “Cookery,” the poet Frederick Turner has written, “transforms raw nature into the substance of human communion, routinely and without fuss transubstantiating matter into mind.”11 Couldn’t much the same be said about the making of gardens? Perhaps the old puritan antagonism between nature and culture is at last relaxing its hold on us. If we are finally willing to sanction the mingling of these long-warring terms on our dinner plates, then why not also in our yards?

That would be very good news for the quality of our gardens, and also, in turn, for the quality of our thinking about the environment. For if environmentalism is likely to be a boon to the American garden, gardening could be a boon to environmentalism, a movement which, as I’ve suggested, stands in need of some new ways of thinking about nature. The garden is as good a place to look as any. Gardens by themselves obviously cannot right our relationship to nature, but the habits of thought they foster can take us a long way in that direction—can even suggest the lineaments of a new environmental ethic that might help us in situations where the wilderness ethic is silent or unhelpful. Gardening tutors us in nature’s ways, fostering an ethic of respect for the land. Gardens instruct us in the particularities of place. Gardens also teach the necessary, if still rather un-American, lesson that nature and culture can be reconciled, that it is possible to find some middle ground between the wilderness and the lawn—a third way into the landscape. This, finally, is the best reason we have to be optimistic about the garden’s prospects in America: we need the garden, and the garden’s ethic, too much today for it not to flourish.

My subject is the future of the garden in America. My conviction is that gardening, as a cultural activity, matters deeply, not only to the look of our landscape, but also to the wisdom of our thinking about the environment.

When I speak of the future of gardens I have two things in mind: literal dirt-and-plant gardens, of course, but also the garden as a metaphor or paradigm, as a way of thinking about nature that might help us move beyond the either/or thinking that has historically governed the American approach to the landscape: civilization versus wilderness, culture versus nature, the city versus the country. These oppositions have been particularly fierce and counterproductive in this country, and deserve much of the blame for the bankruptcy of our current approach to the environment.

One fact about our culture can frame my argument: the two most important contributions America has made to the world history of landscape are the front lawn and the wilderness preserve. What can one say about such a culture? One conclusion would be that its thinking on the subject of nature is schizophrenic, that this is a culture that cannot decide whether to dominate nature in the name of civilization, or to worship it, untouched, as a means of escape from civilization. More than a century has passed since America invented the front lawn and the wilderness park, yet these two very different and equally original institutions continue to shape and reflect American thinking about both nature and the garden. I would argue that we cannot address the future of gardening in America—and the future of the larger American landscape—until we have come to terms with (and gotten over) the lawn, on the one side, and the wilderness, on the other.

As the unlikely coexistence of these two contradictory ideas suggests, we tend reflexively to assume that nature and culture are intrinsically opposed, engaged in a kind of zero-sum game in which the gain of one entails the loss of the other. Certainly the American landscape that we’ve created reflects such dichotomous thinking: some eight percent of the nation’s land has been designated as wilderness, while the remaining ninety-two percent has been deeded unconditionally to civilization—to the highway, the commercial strip, the suburban development, the parking lot, and, of course, the lawn. The idea of a “middle landscape”—of a place partaking equally of nature and culture, striking a compromise or balance between the two—has received too little attention, with the result that the garden in America has yet to come into its own.

This assertion might seem unfairly dismissive. Certainly there are many beautiful gardens in America, and many gardeners who garden well and seriously. But would anyone argue that American garden design can match, in scope or achievement, American music or painting or literature or even—to name one of our newer arts—American cooking? Of course, even to draw such a comparison will probably strike some as absurd, since our culture does not generally regard gardening as an art form at all. Historically, American gardens have been more utilitarian than aesthetic or sensual. As a result, the United States, which in this century has made large contributions to virtually all of the arts, has produced very few landscape designers who can claim international reputations. Almost the only American landscape artists known internationally are golf course designers, whose talents are in great demand worldwide. Given our infatuation with the lawn, this isn’t too surprising. But why isn’t there a single American garden designer with the international renown of a Robert Trent Jones?

Whether the wilderness ideal or the convention of the front lawn is more to blame for this situation is debatable. But one indisputable fact strikes me as particularly significant: the lawn and the wilderness were “invented” during the same historical moment, in the decade after the civil war, around 1870. This suggests that these two very different concepts of landscape cannot only coexist but may even be interdependent. In fact, the wilderness lover and the lawn lover probably have more in common with one another than with the American gardener. But before addressing the prospects for the American gardener, I want briefly to address the history of his two adversaries.

Wilderness

On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the act that designated more than two million acres in northwestern Wyoming as Yellowstone National Park; thus was created the world’s first great wilderness preserve. Grant was responding to a brilliant campaign on behalf of wilderness preservation waged by (among many others) Henry David Thoreau and Frederick Law Olmsted. Why should the peculiar idea of preserving wilderness arise at this time? Clearly, it owed to the fact that the wilderness was disappearing; as early as 1850 visionary Americans began to realize that the frontier was not limitless, and that, unless action were taken, no wilderness would be left to protect. America grew rapidly in the period following the Civil War—and so too did the movement to preserve at least a portion of the fast-receding western wilderness. It’s remarkable how quickly the movement developed, given that half a century earlier the wilderness had been demonized as worthless, heathen, unregenerate—the haunt of Satan. Of course, the appreciation of wild nature was an invention of the late 18th century, of the Romantics—and more specifically, an invention of people who lived in cities. The urbanization of America in the second half of the 19th century formed the essential, indispensable context for the creation of the wilderness park—a good example of the mutual interdependence of civilization and wilderness.

From a philosophical perspective, the romance of “undisturbed” land has done much to keep American gardens from attaining the distinction and status of the other arts in this country. Our appreciation of wild land was not, as in the case of the English, primarily aesthetic—it was imbued with moral and spiritual values. The New England Transcendentalists regarded the untouched American landscape as sacred. Nature, to Ralph Waldo Emerson and his followers, was the outward symbol of spirit. To alter so spiritual a place, even to garden it, is problematic, verges, in fact, on sacrilege. For how could one presume to improve on what God had made? Emerson himself was an accomplished gardener, but gardening rarely figured in his published writing. This was, I suspect, because he could not reconcile his sense of the sacredness of untouched land with the gardener’s faith that the landscape can be improved by cultivation. I’m convinced this unresolved conflict forced him into a bit of intellectual dishonesty. It was Emerson who tried to pass off the truly dangerous idea—at least from the gardener’s point of view—that there is no such thing as a weed. A weed, he wrote, is simply a plant whose virtues have yet to be discovered. “Weed,” in other words, is not a category of nature, but a defect of our perception.

Thoreau brought this idea with him to Walden, where it got him into practical and philosophical trouble. As part of his experiment in self-sufficiency, Thoreau planted a cash crops of beans. In general, as observer and naturalist, Thoreau refused to make what he called “invidious distinctions” between different orders of nature—it was all equally wonderful in his eyes, the pond, the mud, even the bugs. But when Thoreau determines to “make the earth say beans instead of grass”—that is, when he begins to garden—he finds that for the first time he has made enemies in nature: the worms, the morning dew, woodchucks, and, of course, weeds. Thoreau describes waging a long and decidedly uncharacteristic “war . . . with weeds, those Trojans who had sun and rain and dew on their side. Daily the beans saw me come to their rescue armed with a hoe, and thin the ranks of their enemies, filling trenches with weedy dead.” He now finds himself making “invidious distinctions with his hoe, leveling whole ranks of one species, and sedulously cultivating another.”1

But weeding and warring with pests wrack Thoreau with guilt, and by the end of the bean field chapter he can’t take it any more. He trudges back to the Emersonian fold, renewing his uncritical worship of the wild. “The sun looks on our cultivated fields and on the prairies and forests without distinction,” he declares. “Do not these beans grow the woodchucks too? How then can our harvest fail? Shall I not rejoice also at the abundance of the weeds whose seeds are the granaries of the birds?” Unable to square his gardening with his love of nature, Thoreau gives up entirely on the garden—an act with unfortunate consequences not just for the American garden but for American culture in general. Thoreau went on to declare that he’d rather live hard by the most dismal swamp than the most beautiful garden. And with that somewhat obnoxious declaration, the garden was effectively banished from American literature.

The irony is that Thoreau was wrong to assume his weeds were more natural or wild than his beans. Apparently he wasn’t aware that many of the weeds he names and praises as native actually came from England with the white man; they were as much the product of human intervention in nature as his beans were. Far from being a symbol of wildness, weeds are, in fact, plants that have evolved to take advantage of peoples’ disturbance of the soil. One of the casualties of our romance of wildness is a certain blindness: we no longer see the landscape accurately, no longer perceive all the changes we’ve made (not all of which are negative). All too often when we admire a landscape we assume it’s natural—God’s work, not man’s. Many New Yorkers, perhaps most, have no idea that Central Park is a garden: a designed, man-made landscape. Even people who know about Olmsted and recognize his genius tend to suspend their disbelief and experience the place as “natural,” seeking in Central Park the satisfactions of Nature rather than of Art. Historically Americans have tended to experience the great park less as an element of the city, something specific to urban life, than as a temporary, dreamy escape from urban life, an antidote to the city. We can see how even our urban park tradition is founded on the inevitable antagonism of nature and culture, rather than on an attempt to marry the two.

Any culture whose literature takes for granted the moral superiority of wilderness will find it hard to make great gardens. Its energy will be devoted to saving wilderness rather than to making and preserving landscapes. For the same reason, Americans are reluctant to aestheticize nature, to draw distinctions between one plant and another, to proudly leave our mark on the land. And when we do make gardens, we tend to favor gardens that are “wild” or “natural”—but “the wild garden” and “the natural garden” strike me as oxymorons.

A natural or wild garden is one designed to look as though it were not designed. Whether a wildflower meadow, a bog, or a forest, such gardens are typically planted exclusively with native species and designed to banish any mark of human artifice; sometimes they’re called “habitat gardens” or, more grandly, the New American Garden (though they are neither New nor American).

There’s a strong whiff of moralism behind this movement, not to mention a disturbing streak of anti-humanist sentiment. Ken Druse, perhaps the leading popular exponent of the school today, makes clear that the aim of the natural garden is not to please people. “It’s no longer good enough to make it pretty,” he writes; the goal is to “serve the planet.”2 Obviously, the natural gardeners have not rethought the historic American opposition between culture and nature—between the lawn and what becomes, in their designs, a pseudo-wilderness. They assume we must choose between “making it pretty” and “serving the planet”—between human desire and the needs of nature. I propose that the word “garden” instead be reserved for places that mediate between nature and culture rather than force us to make a choice that is not only impossible but false.

Natural gardeners seem convinced that human artifice in the garden is actually offensive to nature. This is an exceedingly peculiar notion. A few years ago, I published an article detailing my first attempt to plant a natural garden. It was a disaster: the weeds quickly triumphed, and the wildflower meadow I envisioned soon degenerated into a close approximation of a vacant lot. I concluded the article with some fairly banal observations about the benefits of planting annuals in rows. Weeding is made easier, of course, but I also found some elemental satisfaction in making a straight line in nature. I quickly discovered that straight lines in the garden have become controversial in this country. In one of several letters to the editor, a landscape designer from Massachusetts charged that by planting in rows I was behaving “irresponsibly.” By promoting even this small degree of horticultural formalism, this critic argued, I was contributing to the degradation of the environment, since gardening “according to existing aesthetic conventions” relied excessively on fertilizers and herbicides. “Nature abhors a straight line,” my correspondent claimed, quoting William Kent, the great 18th-century English landscape designer.

Natural gardeners have a point insofar as they advocate organic methods. But the formal garden is not inherently less environmentally responsible than a so-called natural garden. A “wild” garden is not intrinsically healthier, or more preferable to nature, than a well-tended parterre. A garden’s ecological soundness depends solely on the gardener’s methods, not on his aesthetics.

Speculation about what nature does and does not like has inhibited Americans from learning about form in garden, which seems to me a prerequisite to making good ones. Indeed, at its most essential level, gardening is a process of giving form to nature, an activity neither inherently good nor bad; history shows it can be done well, or badly. The forms we use in shaping our land can be subtle, even imperceptible, though I suspect that most of us will fare better with strongly articulated forms—it takes the genius of an Olmsted or a Jens Jensen to make a satisfying garden with less. Most of us who try to create “free-form” gardens make slack, uncompelling spaces. Straight lines are one of the gardeners great tools, and I am convinced that nature couldn’t care less whether gardeners plant their annuals in straight lines or meandering drifts.

Michael Pollan is editor-at-large of Harper’s; his books include Second Nature: A Gardener’s Education (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1991) and A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder (Random House, 1997). This essay is adapted from a lecture he recently delivered at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.