Fear of Mice

Cats, the longest-running show on Broadway, is in its sixteenth year at the Wintergarden Theater, a few blocks north of Times Square, but the fear of a mouse has become the dominant trope in the current debate about Times Square redevelopment. Listening to some critics wax apocalyptic about the effects of Disney’s invasion of the inner sanctum of New York popular culture reminds me of how much the Nazis hated Mickey Mouse. To them he symbolized the pollution of authentic German culture; the mouse was dark, filthy, a carrier of disease, a threat to the body politic and to the body of the nation.1 Within Germany of the 1930s, of course, the mouse was the Jew. In the 1940 propaganda film, The Eternal Jew, the Jewish Diaspora is represented as swarms of migrating rodents invading, destroying, and controlling every part of the globe. It was a theory of globalization avant la lettre: intensely paranoid, conspiratorial, and murderously ideological. Reacting to the success of Disney movies in Germany, the Nazis focused on Mickey’s blackness, warned of the “negroidization” (Verniggerung) of German culture, and thus conflated Disney with their attack on jazz as that other mode of American, i.e., un-German, culture that needed to be excised. Louis Armstrong and Benny Goodman—this black-Jewish combination repre- sented the ultimate overdetermined cultural threat to the Aryan race. Given their phobia about mice, the Nazis were unable to see how well Disney fit into their own ideological project: cleanliness, anti-urbanism, chauvinism, and xenophobia combined with a privileging of grand spectacle and mass entertainment as organized by Joseph Goebbels’s ministry of illusion.2 The Aryan beauty might have come to love the American “beast,” but the match between Nazi Germany and Disney was never to be.

The Transformations of Times Square

The Nazis had their own version of Disneyland, a world without mice, to be sure, based on deadly serious monumentalism rather than on animated fantasy, but also predicated on control, spectacle, simulacra, and megalomania. In architecture, it was epitomized by Albert Speer’s Germania, the new capital of the Thousand-Year Reich, designed in the late 1930s and scheduled to be built by 1950. American and British bombers cleared the ground—so to speak—for Germania’s north-south axis in the center of Berlin; their success guaranteed that it would never be built. Instead, the Germans, like everyone else in the Europe of the Cold War, got Disney. And jazz, and blues, and rock and roll. To German teenagers in the 1950s, all of these American cultural imports—only later decried as cultural imperialism—were a blast of fresh air from a window opened onto the world, enabling a whole generation to define itself untraditionally in the midst of the rubble and ruins of the Third Reich. Even reading Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck could count as an act of resistance to that “authentic” German popular culture that had survived the Third Reich, that was force-fed in the schools in Volkslied choirs, and that dominated the film industry in the form of the Heimatfilm, or homeland film. Obviously, Disney and its effects are a complicated story, hard to reduce to a neat narrative.

Of course, the comparison between today’s Disney critics and the Nazis is unfair. Another time, another politics: true enough. And yet, how well the Nazi image of the mouse fits Times Square; not the Square of today, to be sure, but the Square before the current redevelopment, the Square with sex shops, sleaze, drugs, prostitution, child abuse, urban decay. Forty Second Street had it all. Ever since, we’ve witnessed the irreconcilable antagonism between the ideological clean-up crews of the right and the romantics of marginality of the left. But, as with the Nazis, a mythic image of a better past is conjured up by both sides in their efforts to fend off change.

But if the trope of nostalgia has throughout history proven attractive as a short-term strategy, it has also proven elusive in the long run; for it is unable to anchor its mythic notion of authenticity in the real world. Authenticity, it seems, always comes after—it is experienced largely as memory, and primarily as loss. In city culture, in particular, the new that we now resist is bound to become, in the future, the basis for a past that we will glorify. One is tempted to side with Bertolt Brecht against the good old days and in favor of the bad new ones. It is not, in fact, self-evident that the mere presence of a Disney store and theater in Times Square will transform that whole space into an urban Disneyland. After all, New York ain’t Anaheim, and the transformation of Times Square involves much more than the presence of entertainment conglomerates such as Disney, Bertelsmann, and Viacom. In its latest incarnation, at any rate, Times Square seems a lot more attractive than what was being planned a mere ten years ago. Have we forgotten Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s office towers, which (to widespread relief) went on hold after the 1987 stock market crash? Rather than turning Times Square into an office wasteland populated by gray guys in three-piece suits, the current redevelopment, directed by Robert A.M. Stern, acknowledges the space as a center of theater, entertainment, and advertising culture. That is something to build on. It is already almost traditional.

This is not to embrace Disney as panacea, and Disney’s presence in Times Square may indeed presage urban developments that are not altogether salutary. But we should speak of them in a different key; at this point, our reaction need not be a flight toward some notion of a residual or uncontaminated higher culture, followed inevitably by a lament about the relentless commercialization of culture connected with the Disney empire. The Times Square phenomenon is symptomatic of a reorientation of the axes of cultural debate. The fissures are no longer between high and low, elite and commercial culture, as they were in the postmodernism debates of the 1970s and 1980s; the divisions are now within the realm of the “popular” itself. Indeed, even the debate in the 1930s between Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin about mass culture, which has become a reference point for those who would turn the old hierarchy on its head, cannot be reduced to the simplistic dichotomy of “high” versus “low.”

Early on, Adorno understood the insidiously reactionary aspect of Disney’s project, locating it within what he construed as the sadomasochistic glee of cinema audiences who laughed whenever the little guy gets punished or beaten up: the Donald Duck syndrome, mass culture as mass deception and collective sadomasochism.3 Adorno’s condemnation of Mickey Mouse was as total as that of the Nazis, but his reasons concerned class rather than race. Walter Benjamin famously disagreed with Adorno’s assessment; his more positive view of Mickey was based upon his insights into how modern media can radically alter modes of perception, how the media can explode fixed perceptions of time and space, and even how the cartoon mouse on celluloid might represent some dreamed-of reconciliation between media technology and nature. Even then the issue was not simply the judgment of high versus low, but rather the evaluation of a commercial mass culture whose forms were transported and shaped by new media. And this remains the issue today. Thus the debate about Times Square involves the sparring of two different concepts of mass culture, of the popular: one that is clean, mainstream, and suburban, and another that invariably identifies the truly popular with notions of marginality, otherness, and minority culture. Both views are narrow, and it is not clear why Times Square should be shaped to accord with either.

In any case, the questions of high versus low that marked the postmodernism debate are irrelevant to discussions of Times Square today. It is too easy to accuse the prophets of Disney-doomsday of harboring intellectual and high cultural prejudices against the pleasures of mass culture. And some of their arguments against the Disney empire are absolutely on target, and not linked to the high/low opposition. In fact, their ideological critique of the Disney vision of mass culture might have been taken straight from Adorno, an “elitist” theorist with whom most of today’s American Disney critics would refuse to have any traffic.

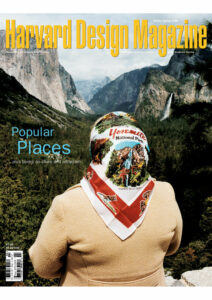

What is at stake with Times Square, in my view, is the transformation of a fabled place of popular culture in an age in which global entertainment conglomerates are rediscovering the value of the city and its millions of tourists for their marketing strategies.4 The Times Square redevelopment project pits those who lament the loss of an older, somehow “authentic” Times Square—whether the allegedly healthy incarnation of the 1940s or the grimy, X-rated, and decayed district of more recent vintage—against those who are open to change but unsure about what change will mean in terms of economics, traffic, ambiance, and vibrancy in this symbolic center of Manhattan.

There will, of course, be some mall-like environments in the new Times Square, and there will be more themed restaurants and shops, but you can’t blame all that on Disney. The mall has invaded the city and it is here to stay. Walk into the Marriott Marquis (built in the Reagan age as a fortress against 42nd Street sleaze) and you will find New Jersey in New York—a wholly suburbanized urban space, complete with predictable greenery, mall-ish escalators, and inside/outside high-speed elevators that, like a vertical Garden State Parkway, transport you quickly to your destination. However, this vertical suburbia offers stunning views of the urban scene: from the eighth-floor revolving bar, one can see the panorama of Times Square, the flashing billboards, the crowds, the streams of cars and taxis, the city as artificial paradise of color, movement, and light. The provision of such a view is itself a powerful argument that the real suburbia does not completely satisfy its inhabitants, who are flocking back to the city as tourists and consumers in search of amusement.

And here emerges the larger problem, which I would describe as the city as image. This is a problem New York shares with other major 19th- and 20th-century cities struggling to maintain their role as centers of business and commerce while also transforming themselves into museum-like environments for an increasingly globalized cultural tourism. This discourse of the city as image involves politicians and developers who seek to guarantee revenue from mass tourism, from conventions, and from commercial and office rents; central to this new urban politics are aesthetic spaces for cultural consumption, blockbuster museum shows, festivals, and spectacles of many kinds, all intended to lure that new species of city tourist—the urban vacationer or even the metropolitan marathoner who has replaced the older leisurely flaneur (who in any case was always portrayed as a dweller rather than a traveler). Clearly, there are downsides to this notion of the city as image, as museum or theme park. But one has only to compare the current Times Square development to the SONY project in Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz to lay to rest such worry.5 The famous hub between east and west Berlin is in great danger of becoming a high-tech mall, for the SONY Center is being built on a site that has been, for fifty years, a wasteland. In contrast, Times Square has retained its urban energy and verve, and this is not likely to change. No doubt the new Square will attract more tourists, but perhaps it will also draw larger audiences to its theaters, and this in turn may bring various related enterprises that will help revitalize the area.

None of this, however, requires us to celebrate the new Times Square as if it were a kind of art installation, the apotheosis of a commercial-billboard culture that has now become indistinguishable from real art, as was suggested, rather too triumphantly, by an article in the New York Times.6 Earlier in this century the Austrian critic Karl Kraus had a point when he insisted that there is a difference between an urn and a chamber pot, and divided his contemporaries into those who used the chamber pot as an urn and those who used the urn as a chamber pot. But if it is now common practice to do both at once, which seems the case in much postmodern culture, then perhaps we should reconsider such distinctions. Distinctions are important to make when discussing the transformations of urban space that result from the new service and entertainment economies. There are good reasons to believe that Times Square will remain a site of urban diversity rather than devolve into a colony of the Disney empire. Let’s not forget that Disney’s lease of the corner of 42nd Street and 7th Avenue is temporary. Disney’s New York experiment may fail, and the office towers may still be built.7 Which occurrence would, no doubt, render the Disney Times Square an object of nostalgia.

Andreas Huyssen is the Villard Professor of German and Comparative Literature at Columbia University; his most recent book is Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia (Routledge, 1995). The author wishes to thank Mary McLeod for comments and suggestions. A version of this essay was first presented at a March 1997 symposium, “Times Square: Local to Global,” sponsored by the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation.