Let’s Try to Be Relevant

Sarah Whiting joined the GSD as dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture in July 2019. A typical short biography would, rightly, portray her as a committed educator and practitioner. But her interests—and the way she translates them into her everyday work—defy traditional labels. She has written texts that turned or expanded certain disciplinary discussions, was Reviews editor for the journal Assemblage, and is founding editor of the single essay book series Point. Our conversation, unsurprisingly, flows swiftly through architecture, politics, history, the immediate present, and the importance of time.

FLORENCIA RODRIGUEZ

My first question is undoubtedly conditioned by bumping into Gropius’s buildings every morning during my walks here in Cambridge. In a way, America was transformed by many of the European modern pioneers’ projects, but of course the Europeans were also transformed by the war and by their arrival in such a different and open culture. I like the way Beatriz Colomina illustrates this in Domesticity at War,1 by comparing two pictures of Gropius. In the first one he is in Paris and he looks very serious and formal. But when you turn the page, you find a very different situation: He looks relaxed in the winter garden of the house he built in Lincoln, here in Massachusetts. The picture is more centered on his wife, Ise, and they really seem to be enjoying a very intimate and peaceful atmosphere.

SARAH WHITING

Have you seen the photo where he’s playing Ping-Pong in the Lincoln house? It’s great. . . . I’ll send it to you.

FLORENCIA

Oh, I haven’t seen that one. But yes, he was evidently transformed by the new context, and immersed in the spirit of a new world. In fact, it is said that when people talked about his house as an example of European modernity or International Style, he would argue that it was very New England.

There are other experiences, such as Mies’s, or other European artists and architects that got together at places like Black Mountain College. So I wanted to start the conversation by asking what kind of impact that had locally, and how did it affect American architecture?

SARAH

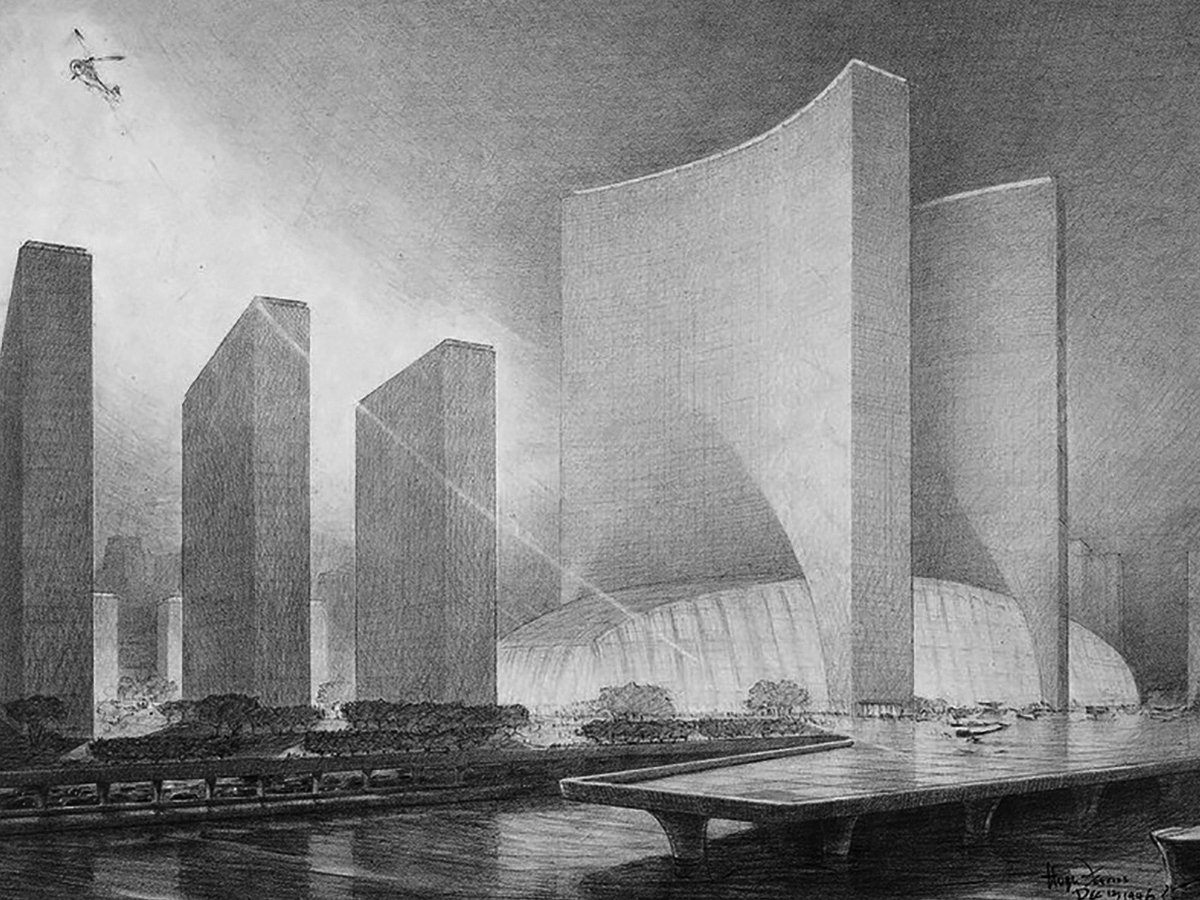

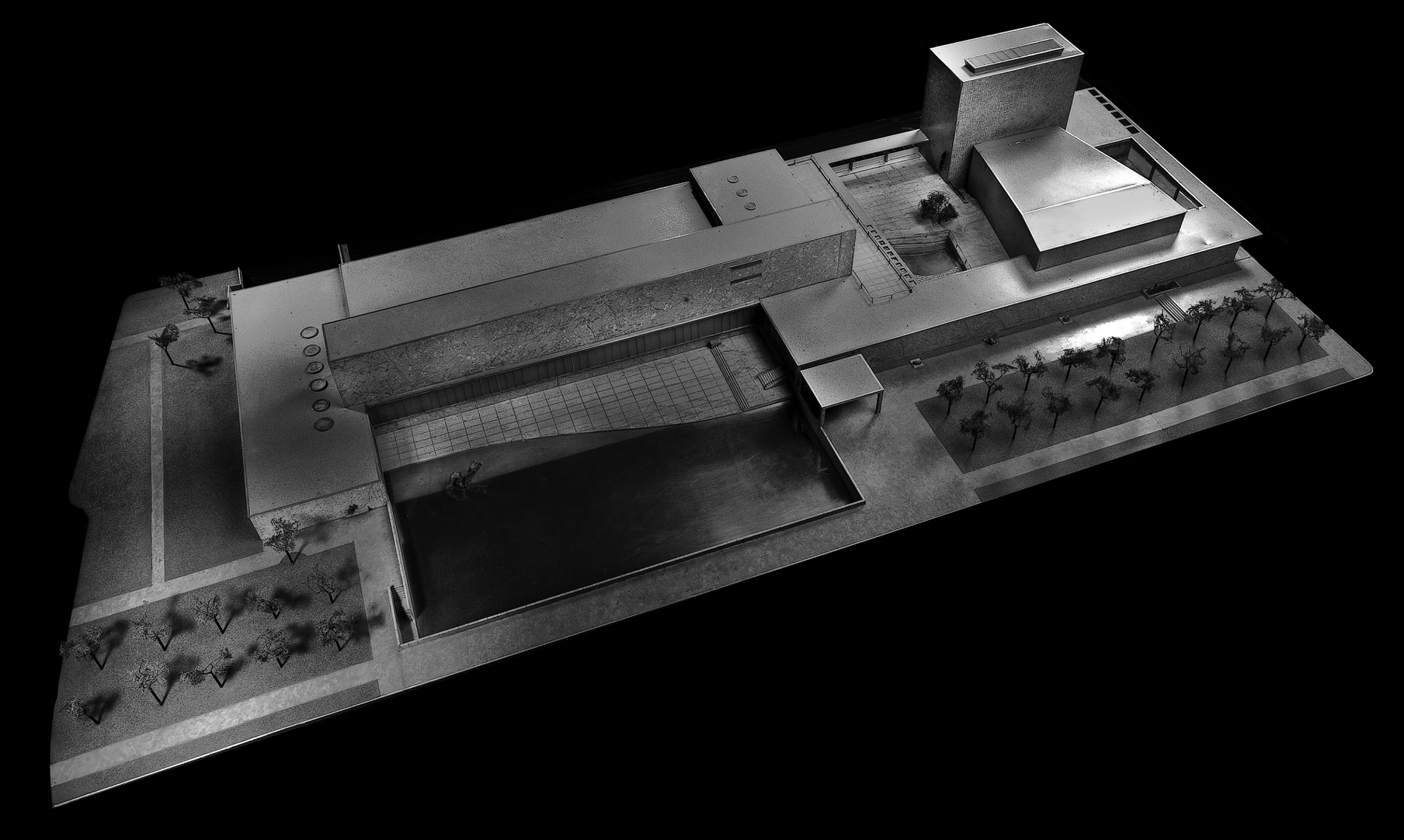

I warn you that this is part of my dissertation—“The Jungle in the Clearing: Space, Form, and Democracy in America from 1937 to 1952”— so I could talk for hours! The dissertation grew from the fact that with World War II, the US assumed a new role upon the international stage: architects and planners were suddenly tasked with what that looked like architecturally and urbanistically. Part of what I elaborated on was the struggle for a new civic language—a new identity that would manifest itself particularly through public and civic buildings. I focused upon the discourse of that moment (including the debates over this topic), some examples of civic structures from that time, and then finished with a case study on what kind of modern city emerged from this new identity and from this new approach to a public language. That final section looked at midcentury Chicago—specifically the Near South Side (just south of the Loop) between 1938 and 1960.

This discourse about a civic language for architecture was instigated by expat Europeans, who came to America, not necessarily out of desire, but because they were fleeing the war and found themselves together in New York. So there was a concentration of incredible art, architecture, and urban minds all together in Manhattan. And they all had time to pause . . . time to think . . . time to talk. This “pause” led to important collaborations, like the “Nine Points on Monumentality”2 text that Sert, Léger, and Giedion wrote for the American Association of Artists. A number of similarly significant texts come out of this moment, dealing with topics like monumentality and civicness.

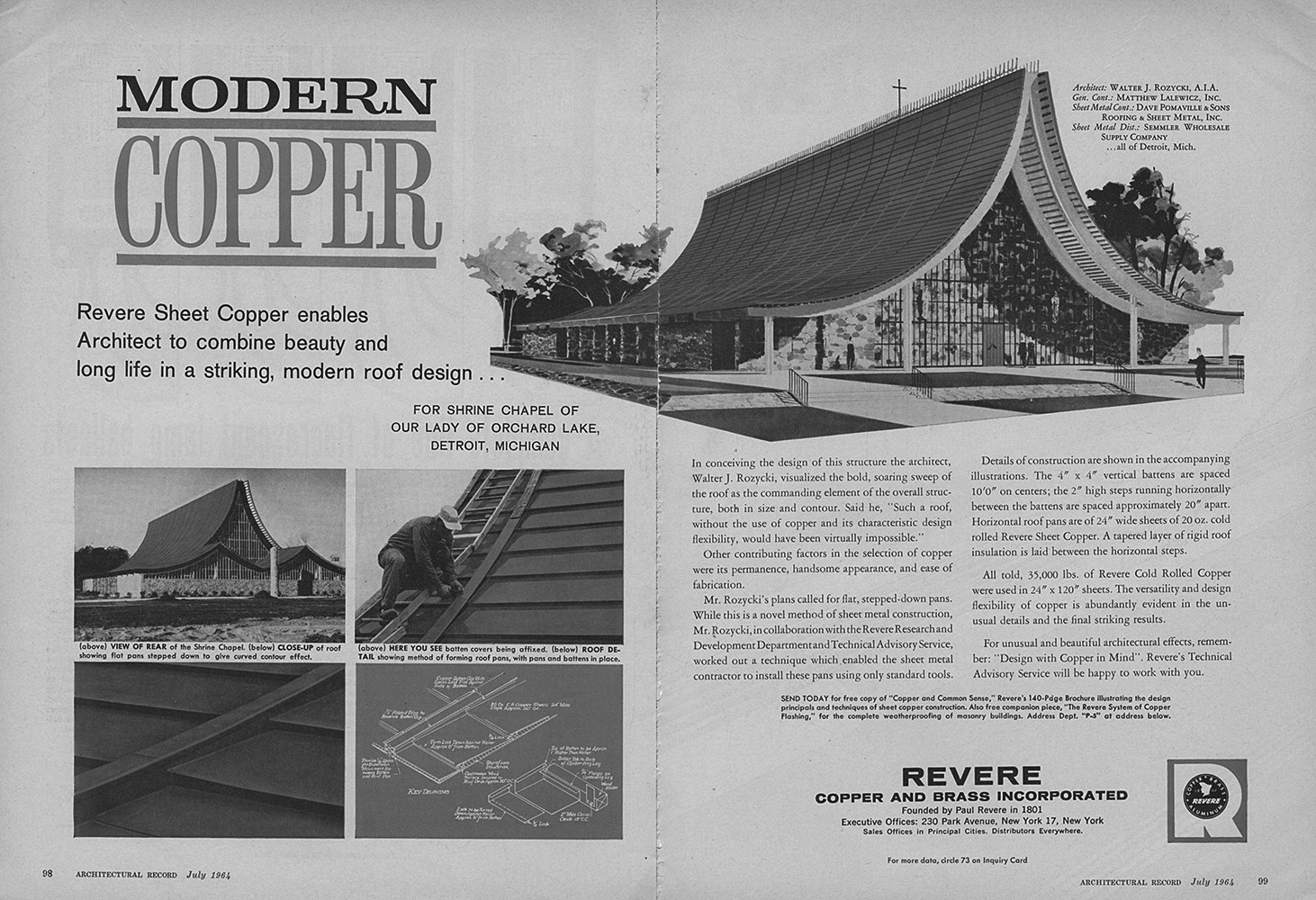

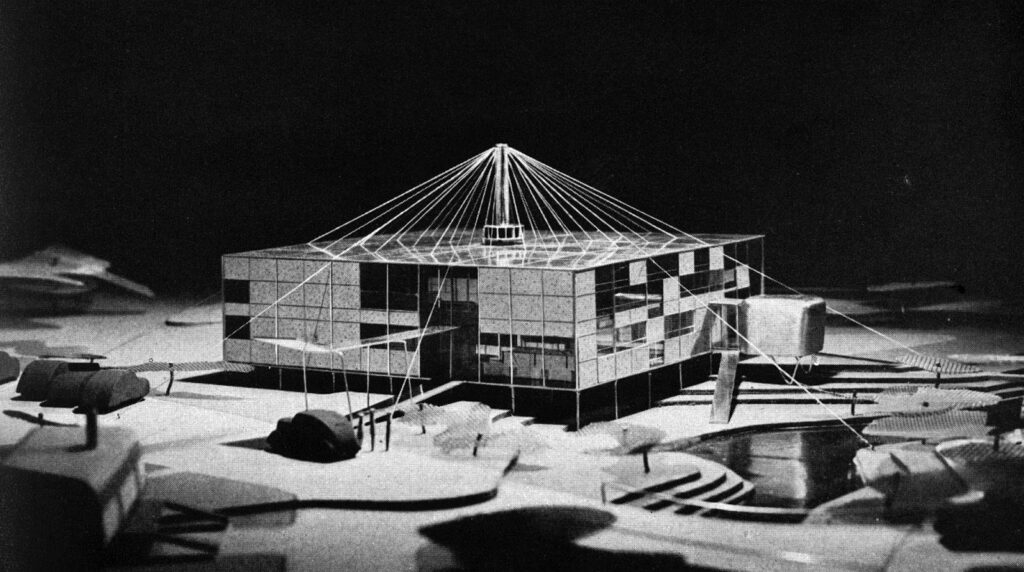

What interests me about this period is that on the one hand, there was a sophisticated, disciplinary discourse about the language and the future of modernism taking place in museums, in exhibitions, in magazines, in schools. Alongside that was an equally active business or corporate conversation: architectural research into new materials, new programs, and new uses was being underwritten because manufacturers wanted to make sure that materials that had been developed for the war could have future markets as building materials. Companies like US Gypsum and Revere Copper and Brass were sponsoring design research. There’s a great set of ads, for example, that US Gypsum ran in Architectural Forum; each month featured a different design by an architect using their material, including Eero Saarinen’s vision for a “demountable space”—a civic center that could be moved around thanks to its single mast structure and light materials (gypsum, of course). All in all, it was a remarkable moment where there was time, urgency, a clear agenda, and research funding for design.

FLORENCIA

And an industry that was very eager to respond to that.

SARAH

In a way, that moment meant the construction, or constitution, of the global image that American institutions wanted to communicate and spread. It is interesting to overlap the territorial plans made for industry, for corporations, education, and the other programs that defined this model.

FLORENCIA

When comparing similar phenomena in other parts of the world, what seems to have been missed is such clarity in territorial scale and strategy. Also, in other regions of the Americas, for instance, modernism stayed as an intellectual canon that became limiting and didn’t promote other modes of thought about the built environment.

Brazilian architecture and its modern pioneers were so strong and outstanding that they are still hard to overcome. I guess there are other facts that anchored Latin America to that particular moment in history. Even though the fundamentals of modernism were generated first in Europe, there were so many great local architects committed to a new way of thinking and making architecture, that all of their production had a significant regional and postcolonial impact. That also had international significance at the time. In one of the introductory texts in the catalog3 for MoMA’s “Latin America in Construction. Architecture 1955-1980,” Barry Bergdoll quotes the press releases and comments about the museum’s previous exhibitions on Latin American modernism—held in the first half of the 20th century—that show how they were seen as possible models for the future, when projecting a postwar scenario.

The problem is that Latin American modernism is still taught in some architecture schools tainted with a huge load of romanticism. I guess that, in addition to political facts, that’s why postmodernism, or other intellectual trends, didn’t permeate as much in Latin America. They didn’t fairly reflect what people were going through.

SARAH

You have what happens in the academic realm and then you have what happens in practice. And in the postwar period, there’s a blurring of the distinctions between the two; Joan Ockman, Reinhold Martin, and Mark Jarzombek have all written important pieces about this moment. Mark has a beautiful little article in the Cornell Journal of Architecture called “Good-Life Modernism and Beyond,”4 where he’s essentially talking about the softening and rendering of modernism for a consumer market.

That “good-life modernism” is quite different from what you could call the “straight up modernism” that continued to thrive in Latin America (let’s acknowledge that we’re painting a very broad-brush historical vision here, of course). Keep in mind that this perfect storm of overlaps in the United States—the war, the time or pause that gave practitioners, and the corporate patronage or sponsorship—coincided with the fattening of the American economy.

I was just listening to a terrific podcast discussion about neoliberalism5 and I think the notion of the consumer class that emerged here in the 1950s is very different than in Latin America. During this moment of “fattening,” there was a clear flattening of the American public into a middle class that fed off of the shift to a service economy and that manifested itself urbanistically in the rapid and homogeneous growth of American suburbia. But underserved populations in the US didn’t experience the same level of economic fattening of the middle class during this postwar period, and I suspect that the rest of the Americas also didn’t have this same middle-class growth. Today in the US we have seen the fallout of the inequities of this expansion for many populations, particularly Black Americans. We have also started to see that middle class shrink—and fast. We are more and more in a world of a small group of “haves” at one end of the economic spectrum and an ever larger group of “have nots” at the other. Maybe now we are becoming more similar to Latin America.

FLORENCIA

Yes, probably. Or the fattening did take place briefly in some countries but got interrupted by dictatorships and other complex global facts related to extraction and other economic deals.

A THEORY OF ARCHITECTURE

FLORENCIA

How do you think the idea of autonomy in architecture grew in the middle of the process you are describing? I’m also interested in how you would link it to the renowned essay you wrote with Robert Somol, “Notes around the Doppler Effect and other Moods of Modernism.”6

During your public conversation with Michael Hays7 you mentioned you felt that piece was too condensed, and that probably because of that, the dialectic of the text received more attention from the readers than its actual prompt.

SARAH

Yes, and again, I’m going to talk here in gross generalizations that should make all responsible historians blanche. . . . That’s a whole topic in itself: history via conversation versus history via deep-dive text.

Anyway, to turn to your question: it’s important to remember that during the postwar period you also get the strengthening of the American university system (largely through federal research funding). Central to the American system is its liberal arts component, which I think differentiates American universities from most other countries. Undergraduates are less “tracked” here—you are encouraged to explore your intellectual freedom and direct yourself as a college student, rather than being tracked already in high school to go into certain educational paths directed by career ambitions. The embrace of this four-year liberal arts exploration gives the space during university studies for an intellectual project. The academic project of architecture, which includes autonomy as well as other topics, flourished in this environment of academic freedom. Architectural autonomy grows out of aesthetic considerations: formal relations, spatial relations, composition, etc. This idea that architecture is an academic discipline with its own intrinsic considerations, could only really happen because of that space existing within the academy in the Anglo-American context.

There is one important thread of architecture as an academic discipline that weaves through Rudolf Wittkower, Colin Rowe, and Peter Eisenman and that defined an autonomous discipline where space was defined by form, not by program or technology. It’s the strength of the liberal arts academy that allows for that room for thinking about the immediate relation between space and form, suspended from other concerns. When disciplinarity was challenged by interdisciplinarity in the late ’60s, it was a challenge that pitted the one against the other: you were either a die-hard disciplinarian, that is, focused on architecture qua architecture, or you were an equally adamant interdisciplinarian, focused on architecture’s relation to other disciplines. This was the beginning of the divide between those interested in form and space and those interested in social spaces. I’m excited to think that we are entering a moment when that artificial divide can be bridged: when we can advance architecture’s formal and spatial relations at the same time that we advance architecture’s social relations. To me, it’s always been clear that the relations between form and space have social repercussions: dimensions, compositions, and proportions impact social relations that happen within and among buildings and public spaces in our world.

FLORENCIA

And maybe the post-1968 moment coincides with the growth of theory of architecture as a discipline in itself, separated from the arts? It was a turning point characterized by a significant proliferation of books and writers.

SARAH

Yes. And significantly, this proliferation was tied to the academy and to institutions. Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture was tied to MOMA; Koolhaas’s Delirious New York and Rossi’s A Scientific Autobiography were both tied to the IAUS (the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, which was an independent think tank that existed in New York between 1967 and 1984). These institutions gave time and space for thinking, writing, and projecting. It’s a very interesting question to think through why that was permitted: why that time and space was given to this project here in the US more than in other contexts around the world. And again, I would say it’s because the American university system had placed a professional education within the larger context of a liberal arts education.

Take the GSD as an example: this is an entirely professional school, but only at the graduate level. So the implication is that everyone comes here after having had a four-year liberal arts education (even if, of course, many students arrive after having completed a professional undergraduate degree somewhere in the US or across the world).

FLORENCIA

And what do you think of trying to extrapolate all of that tradition to the present conditions and crises? What’s the role of theory and criticism today?

SARAH

That role is ever more urgent today, because one primary purpose of theory and criticism is to look carefully and to take time to advance thought. So I would argue there’s absolutely a role, and we have the obligation to figure out how to make that time and how to direct that thought. Fifteen years ago, the luxury of that time was carved out for history and theory—it was naturalized; now people are forced to be (or at least people feel forced to be) more expedient about any time they take for anything. I think this anxiety about time, particularly about time spent, has weakened our thinking and our work more broadly.

FLORENCIA

At the same time, it seems that intellectual trends work as a pendulum going back and forth from something very fundamental to the discipline to other very extreme positions. I’m thinking, for instance, of what was shown and discussed at the last Chicago Architectural Biennial—especially in terms of design and architecture’s difficulty in responding to social urgencies. There seems to be a conflict that contemporary criticism and theory should take on.

SARAH

Well I think there’s still this anxiety—and this also came up in my “fireside chat” with Michael Hays—that if you’re interested in the social, you can’t be interested in form, and vice versa, which I find as curious as it is constipating for the future of any kind of design.

FLORENCIA

I agree.

SARAH

This crisis of the tension between those who think about social issues and those who think about form has been present for a long while in urban theory. Think of someone like Ed Soja, who is an important urban geographer but who has a real aversion to talking about form in space. He doesn’t talk about space as defined by form, but only as defined by action, by people. Why not talk about both? Or even David Harvey, who is fantastic at reading the city and the complexities of economics, but also neglects the subject of built form in his writing. In short, this blind spot was already evident in advanced urban theory a while ago and it’s simply become more urgent today.

Last spring we were all witness to what can only be called a national awakening to the depths and consequences of structural racism in this country. That racism is tied to our design disciplines in a myriad of ways, ranging from issues of access and admission to design academies like ours, to issues of physically defining and separating populations with form at all scales: walls, bollards, and infrastructures of all sorts. Zoning happens through policy, but it has implications on form and space—and, of course, on the social.

When we were at Princeton, Robert Gutman was on the faculty. Bob was a sociologist, but he knew the importance of form and more importantly, he could read form. The most successful schools are those that have figures like Gutman, who don’t represent a kind of rock in the river that’s constantly blocking the flow with a “no, no, don’t do this,” but who instead work with other points of view to advance collective thought. Designers don’t always understand the complexities of the social, the political, and the economic, and I value that a more complex version of those arguments is being put on the table right now. But it behooves us to also engage their formal repercussions. We designers have the training to make those bridges to our disciplines—it’s our responsibility to ensure that those bridges happen. We cannot expect others, who do not have our years of experience learning design, to know how to discuss form and space, and so it is for us to put those topics on the table and to work with other disciplines to understand the repercussions of our formal expertise on all social questions, but also the possibilities we have to shape a better world.

FLORENCIA

And was the idea of “The Doppler Effect” to point out something like that?

SARAH

Yes, we were saying that opposing form and the social is problematic. But it was actually less about the topic of “the social” and more about criticism itself moving away from form, and moving away from architecture, and moving away from depth, and becoming facile. What we were arguing was that criticism had rendered itself powerless. Today’s problem is that criticism has been characterized as being entirely irresponsible. So the essay was foreshadowing something that has only gotten more problematic.

AN EDUCATIONAL PROJECT AND AN IMMEDIATE HISTORY

FLORENCIA

And how do you think this kind of problematic can be translated to an educational project?

SARAH

It’s a great challenge because it really means: “How do you reestablish a foundation of thinking in our disciplines?” It’s probably better not to use the term “theory,” because that term is so associated with a specific body of writing in our field. So how do we reintroduce thinking into the design curriculum? One obvious way is to introduce time for deep thought as opposed to quick thought. Another way is to underscore that today’s rise of the social, the political, and the economic is absolutely relevant. So we need two registers in our thinking and our talking: one that’s within the discipline and the other that’s more broad. Some people are capable of doing both at once. Most people have to be conscious of both, and we definitely have to teach both. I think there was a luxury in the 1970s to have a communication that was purely academic and I don’t think that’s an available luxury anymore. But I also don’t lament it—I am excited that we’re tying design into complex contemporary contexts. We just have to take care that we don’t lose track of the specifics of design along the way.

FLORENCIA

Indeed. I had this kind of intellectual fixation for a period of time about whether criticism had to be “useful,” and I explored that idea differently in many of the interviews I conducted, and in lectures, symposia, and other formats. Even though “useful” is not the best word because of its pragmatic or instrumental implications, I took it as a provocation just to contrast it to that idea of luxurious theory you were pointing out. I guess the real question should be: what kind of criticism should we build on?

SARAH

Instead of useful, I would say relevant. Because “relevance” allows you to say it doesn’t have to be tied to an actual use or to a how-to. What we’re doing has to have resonance or applicability. You have to have an audience of some sort, let’s say. But that’s why relevance is a really useful term to keep on the table. At the GSD, we’re educating a powerful group of students who are going to go out and have the voice of this degree and this institution behind them, and they’re going to be taken seriously before they even say anything. So if we can teach them to be relevant, there will be a bunch of people out there who are championing a new way of thinking. In short, changing the culture of the discipline right now can and should happen first in schools. And spring of 2020 taught us the urgency of being relevant: the pandemic has revealed the relevance of design in creating spaces and places that are more healthy, or at least less risky; and the Black Lives Matter movement has revealed the relevance of design in making populations more visible and distributing basic infrastructure and amenities—including healthy city amenities like open spaces—more equitably.

FLORENCIA

Building on that, I’d like to take us back to the beginning of our conversation and the pivotal era we were discussing. Do you think something from that tradition of American architecture can lead to a contemporary agenda of change, similar to the one you’re suggesting?

SARAH

That’s interesting. I’m not sure. The moment that I looked at in my dissertation is a very useful moment, but it was also a moment of real national hubris. . . . You can see some agendas that worked at two different registers—a public one and a disciplinary one—but you can also see the watering down of an important argument to a kind of soft public response. And maybe that’s a good warning because at a certain point, the social, political, and economic aspirations of modernism were all so easily co-opted by market forces. Joan Ockman has written about this transformation, terming it “normative modernism.”8 That’s something to be wary of today: how do you make something publicly accessible without immediately making it a consumable idea or good? Maybe we never can avoid this dilemma, since design is always implicated in the market, but I think that there are ways we could push, things that we can do, so that we’re not compromised by it.

This is not to suggest that that period, before or after the war, was “golden”—it’s so easy to look back with a false sense of simplicity. We know that federal housing legislation and financing policies that emerged during the New Deal—as well as the urban renewal and infrastructural investments after the war—entrenched segregationist practices across the country, with racist repercussions that continue to impact, isolate, and deprive entire populations.

We have lived through the city being denigrated and the concomitant growth of the suburbs. And now you have this folding back, this densification of the city, which is great. Maybe we can become an urban nation after all. Except of course all large American cities are unaffordable right now. I recently came across an incredible statistic about the percentage of American workers who can actually afford to live in American cities. It’s remarkably small. During the first Obama years and also at the end of the Clinton years, there was excitement about the idea that the urban could be viable again. Where is that excitement now?

FLORENCIA

The city’s density has also proven to be more sustainable . . .

SARAH

Right. Density is absolutely sustainable from an ecological point of view. Manhattan is off-the-charts green, thanks to its density. And yet, then you see the crashing of WeWork, you see what Airbnb has done to cities—all these things that we thought were the tickets to the future. So it’s hard not to become disillusioned by these new economic and social modes that we at first imagined were loopholes in neoliberalism. I think we have to be very careful not to lose hope. Yes, these loopholes, which were thought to be long-term promises, have proven to have their problems. But that doesn’t mean that they are all wrong. . . . Are there ways of looking at micro housing that aren’t just copping to the market? Does housing have to be tiny and inhumane because that’s all you can afford? Are there amenities that we can give back? Are there things that can be shared that aren’t just a high-end concierge service?

And now add to all of these questions the pressures that the urban has experienced during the pandemic: density, which is great from an ecological perspective, was demonstrated to be unhealthy. It can be negative when it stems from economic hardship—dense urban environments were hit especially hard by COVID.

FLORENCIA

It’s interesting that some of the ideas about co-living or shared spaces were explored by many modern architects but weren’t collectively embraced at the time. I think that there was a world that was envisioned and that maybe neoliberalism kind of ate it….

SARAH

Exactly, and has digested it . . . and now the world needs a good dose of Pepto-Bismol.

FLORENCIA

It’s astonishing to realize that the period when many of us were writing and reading about aspects of those sharing economies—in a celebratory, even naive way—was so short and so recent!

SARAH

Exactly; we were utterly optimistic and that optimism ended up being very short-lived. So, on the one hand I think, “Oh man, too bad I wasn’t dean here at the GSD right at the arc of those exciting new models.” On the other hand, I think what’s exciting right now is that we may be at another moment where we can introduce time. World War II introduced time and had a huge effect. The oil crisis of 1973 introduced time. There was very little building at that moment, and that’s when we got the flourishing of Oppositions and other important forms of discourse. Now we should actually take the time to slow down and say, “Uber, Airbnb, WeWork . . . those are not quite the right solutions, but what is the right solution?” Because those attempts were trying to find a collective ambition. So how do we move collective ambition in the right direction? I remain optimistic. I have to.

FLORENCIA

There is a need for new models for sure, and a lot to explore.

SARAH

And maybe that’s another thing that you could attribute to America—a kind of willful optimism that helps fuel this country. We all see one highly dangerous extreme today of a self-absorbed optimism, but I believe that there is still a shared, collective, inclusive optimism that holds promise.

SARAH WHITING, PhD, is dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Cofounder of WW Architecture, she served as dean of Architecture at Rice University for nine years and is an expert in architectural theory and urbanism.

FLORENCIA RODRIGUEZ is an Argentinian architect, writer, and editor. In 2010 she founded PLOT, a publication in Spanish about architecture, and in 2017, aiming for a wider audience, she founded Lots of Architecture, an independent publishing company, and its flagship title, -NESS: On Architecture, Life, and Urban Culture. She was a professor of landscape theory and technology theory in the Torcuato Di Tella University graduate programs and has taught theory courses at other universities. Rodriguez has lectured, curated exhibitions, and organized international symposia. She has published a number of articles in books and specialized media including Domus, Oris, summa +, Arquine, a+u, and Uncube. In 2014, Rodriguez was a Loeb Fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.