Never Let a Crisis Go to Waste

What are the key challenges going forward for American cities? After a year of seismic impacts across urban America—from both the coronavirus pandemic and the growing social justice movement—it’s a pertinent topic for Shaun Donovan. A Harvard-trained architect and secretary of Housing and Urban Development and director of the Office of Management and Budget in the Obama administration, Donovan is now running for mayor of New York City, where he had previously served as the housing commissioner.

Donovan believes that “where someone lives determines so much of the opportunity in their lives.” During his time in Washington, Donovan was a champion of the administration’s Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Rule, which held local governments accountable for promoting affordable housing and community integration. In conversation with Jerold Kayden—urban planner, lawyer, and the Frank Backus Williams Professor of Urban Planning and Design at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design—Donovan discusses America’s current crises and the crucial role that affordable housing policies must play in creating more equitable and inclusive cities for all who call them home.

JEROLD KAYDEN

In the last year, the world has changed. The coronavirus pandemic, George Floyd’s death, and the Black Lives Matter protests have had a dramatic impact on cities. And I should add that in early February 2020, you filed paperwork to run for mayor of New York City. How have these events affected your views of cities and society?

SHAUN DONOVAN

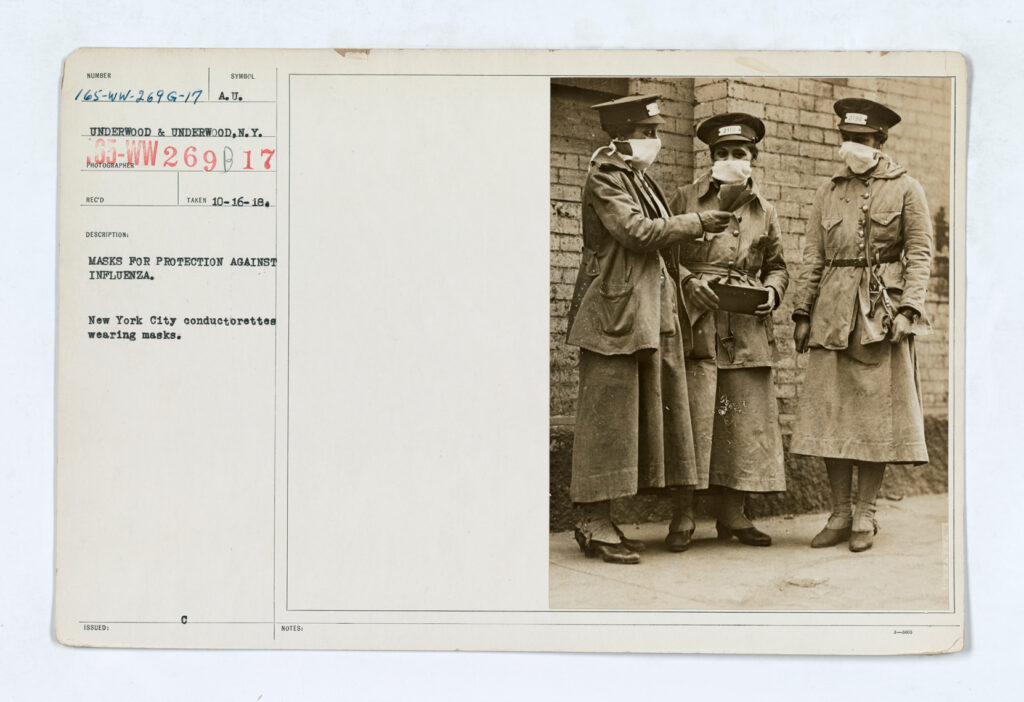

Unfortunately, I wasn’t surprised to see the impact that the pandemic has had on Black and brown people and communities. I say that because Hurricanes Sandy and Katrina and every natural disaster I’ve ever been part of responding to had a disproportionate impact on communities of color. Those who are most vulnerable before the crises always end up being hurt the worst.

Having said that—despite the enormous pain, the widespread death and suffering of people, especially in Black and brown communities—I also believe that the awakening that we’ve seen, the protests in New York City and across the country, really are hopeful signs that America is grappling with the history of race, with our country’s original sin, in a way that can lead to new outcomes. As President Obama used to say to us all the time, “Never let a crisis go to waste.”

JEROLD

The current secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Ben Carson, has essentially pulled a rule that was brought into effect during the Obama administration that implemented a requirement under the 1968 Fair Housing Act for affirmatively furthering fair housing. Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden has attacked that decision and promised to condition certain federal grants on the willingness of suburban communities to revise their zoning ordinances in ways that will permit, rather than prevent, the construction of affordable housing. President Trump has characterized this as an assault upon the suburban way of living. What are your thoughts?

SHAUN

I was in many ways the author of that rule and its greatest champion. It’s surreal to see a racist president attacking one of the most important steps we took during the Obama administration to reverse the structural racism that’s shaped our country for too long. Racist movements often begin with where people can live, with land use. Where someone lives determines so much of the opportunity in their lives: their children’s school, access to jobs, access to healthcare, the availability of fresh food, and on and on. The idea that a president and a HUD secretary could claim that this is social engineering—without recognizing that the whole history of racial segregation in this country was socially engineered—is wrong and shameful. We are where we are today because of redlining done by HUD and the federal government in order to construct segregated neighborhoods.

If we’re going to attempt to make it right, then we have to live up to the words of the Fair Housing Act, which as you said, demanded that we go beyond just stopping intentional discrimination. We have to affirmatively further fair housing, which means taking proactive steps to create inclusive, diverse communities in this country.

Trump and Carson are ignoring that this wasn’t a rule just about the suburbs. Obviously, it’s important that suburbs have for too long constructed policies like exclusionary zoning to keep low-income people of color out. But we also still see too many Black and brown communities with poor schools, sub-par health care resources, and hazardous environments. President Obama and I used to say that we shouldn’t live in a country where a child’s future is determined by their zip code, and yet that is still true in too many neighborhoods. The need for Black and brown communities to have the same kind of opportunities that are available everywhere else has been conveniently ignored by this administration. Again, it goes to the underlying racist views of the president: he’s not going to do anything to try to build up those communities.

This administration has tried to portray the rule as an imposition of federal overreach and social engineering on local communities. But I traveled everywhere in this country as HUD secretary, and I had dozens of conversations with mayors and community leaders—long before George Floyd was killed and the movement for Black lives emerged in the way it has in these last few months—and what I constantly heard was that they were really interested in undoing this legacy of segregation and racism. They needed better data. They wanted to know what the best practices were, and what other communities had done through zoning and other steps.

For the first time ever, we constructed a national index of opportunity that looked at every community in the country. We heard that this was powerfully helpful to mayors. I think there’s even more interest and focus on these issues today. It’s deeply painful that at the very time that we’re having this awakening among American citizens—and among mayors in particular—the federal government is pulling back one of the most important tools.

JEROLD

In a lot of cities, including New York, certain neighborhoods are resistant to the construction of affordable housing. They act like mini suburbs within the city. Those neighborhoods often believe that the construction of more affordable housing in their neighborhood will harm their way of life.

SHAUN

There’s no question that some of the fear you’ve talked about isn’t just in the suburbs, it’s also in city neighborhoods. But given the advances that we’ve made in inclusionary zoning and a range of other tools, there’s very little evidence that density actually undermines property values or quality of life. In some ways, the opposite is true. We now understand the lifesaving importance of having essential workers—nurses, teachers, postal workers—in the community.

I’ve been encouraged by the movement in Minneapolis to eliminate single-family zoning, and the demand in California that communities built around transit hubs create greater density and include affordable housing. We’re beginning to see advocates coming together with local government, state government, people who work in the real estate industry—a strong coalition from across the political spectrum—saying that every community needs to do its fair share in terms of affordable housing and housing density. Changes like these have a sustainability benefit too—so we can address our history of structural racism and at the same time help build a better environment for the future.

JEROLD

Many people say this pandemic has demonstrated that remote working really works. You don’t have to go into the office. You don’t have to commute. You don’t have to take the subway. You don’t have to do a lot of things that underpin the economies of such cities as New York. There are some who celebrate the fact that this will lead to the demise of New York. There are others, like the comedian Jerry Seinfeld, who more or less said in a recent New York Times op-ed, “We’re New Yorkers—don’t ever sell us short.” Where are you on this?

SHAUN

I have a very personal perspective because I grew up in New York City when everyone was predicting the death of the American city with New York as the poster child. I was five blocks from Ground Zero when I watched the second plane hit the World Trade Center. I led the long-term recovery after Hurricane Sandy. In each of those cases, I remember the voices of doom that said the city can’t recover. And yet, it has always recovered. I have optimism about the future of the city because I think New Yorkers are tough and resilient.

I desperately miss the interaction and the companionship, the creativity, all of the things that come out of the random collisions of interesting people. I think back to when the internet was created—there were lots of predictions at places like the GSD that it would be death for cities. In fact, the opposite has happened. It used to be that cities were created where there was access to rivers, railroads, or natural resources. Today people decide where they want to live and companies and capital follow.

So I think that once we get a vaccine or a treatment, a lot of the fear will dissipate. We’ll see that working remotely works in the short term, but it’s not enough for the long term. In the design professions, for example, people don’t design or create in isolation. Technology, science, and industry are powered by innovation. Cultural interactions are possible—even unavoidable—in the city.

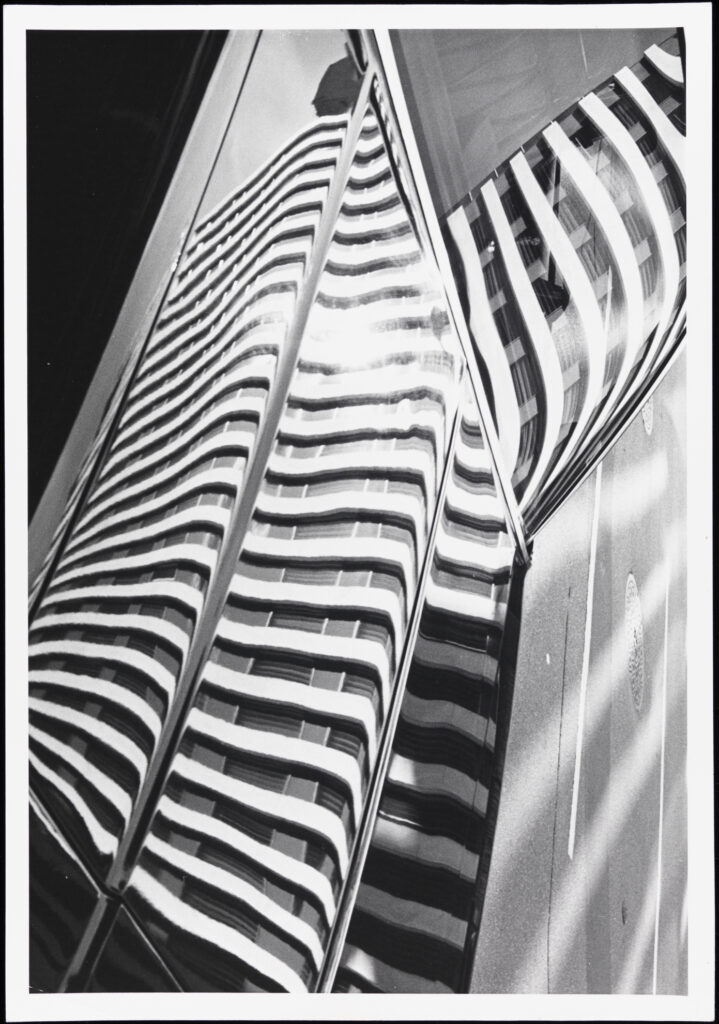

Those fundamental things haven’t changed just because we figured out how Zoom works. I had a conversation with an executive who told me that he would weep tears of joy when he saw the New York skyline again, because he’d been out of the city. I talked to many essential workers who didn’t have the choice to leave the city, and they feel the same. This is their home, their community; this is where they’re rooted. Yes, some people may decide to leave. But the underlying strength of cities is still there.

With the right leadership, I am confident that New York City can recover. But I also believe that the underlying dynamics that have made New York City increasingly unaffordable remain. We can use this as an opportunity to reimagine New York and make it more equitable, sustainable, and inclusive.

JEROLD

Can New York City do this on its own? Isn’t the national government crucial for helping cities come out of this? New York has a multibillion-dollar deficit. People aren’t riding the subways: how does the Metropolitan Transportation Authority manage with a huge drop in revenue?

SHAUN

The federal government stepping in boldly and decisively is absolutely central to creating a quick recovery and reducing as much as possible the pain and suffering of Americans. There’s a lesson from the Great Recession in 2008 and 2009: Congress didn’t do enough in state and local aid and it resulted in layoffs—teachers, municipal workers, state workers. That was one of the primary reasons the recovery took longer than it should have. We desperately need Congress to pass the relief bill that will give almost a trillion dollars of state and local assistance. We may have a housing crisis that’s worse than the Great Recession if we don’t do something right now.

We have people lining up at three in the morning at soup kitchens in the South Bronx to feed their families. It is unconscionable that the Senate would go on vacation when we have desperate need around the country that is getting even more desperate.

SHAUN DONOVAN is a candidate for the mayor of New York City. He served as director of the US Office of Management and Budget and as secretary of Housing and Urban Development in the Obama Cabinet. He also chaired the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force.

JEROLD KAYDEN is the Frank Backus Williams Professor of Urban Planning and Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. His teaching and scholarship address issues of land use and environmental law, public and private real estate development, public space, and urban disasters and climate change. His books include Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience; Landmark Justice: The Influence of William J. Brennan on America’s Communities; and Zoning and the American Dream: Promises Still To Keep.