Spaces of Hope in Uncertain Times

Architecture and urban design create future realities, from buildings to complex urban fabrics. In recent decades, these fields have been shaped by neoliberalism and hegemony more than by creativity, desire, agency, or societal, cultural, and environmental needs. Neoliberalism centers on market needs, deregulation, and privatization; it encourages fragmentation, inflation, competition, consumerism, and efficiency.1 In The Art of Inequality: Architecture, Housing, and Real Estate, Reinhold Martin, Jacob Moore, and Susanne Schindler explain the link between architecture and neoliberalism through real estate: “Architecture gives form to real estate and becomes both evidence and instrument of growing socioeconomic divides.”2

Hegemony, meanwhile, is the political, economic, and military dominance of one state, nation, or group of people over another. Old power structures that struggle to keep the status quo, like the nation-state, are forging systemic segregation through spatial policies based on, for example, nationality, race, or ethnicity. The confluence of neoliberalism and hegemony in architecture and spatial design has resulted in the production of highly segregated spaces.

Creative practices at the intersection of architecture, urban design, art, and activism can promote collective values operating outside neoliberalism and hegemony. Such practices, which are intrinsically multihyphenate, expand the field of architecture and offer, to some extent, a space of critical care and hope. My own work with FAST—the Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory—is inspired by and intersects with the work of Irit Rogoff and Yona Friedman, both pioneers in this area.

I. Inflation/Inflated Field

Over the past few decades, Rogoff, the founder of the transdisciplinary Department of Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London, has published a series of essays exploring artistic and cultural production through the lens of pedagogy and curatorial practices. She has emphasized the necessity of finding ways to liberate the creative disciplines from the neoliberal constraints that hold our imagination and agency hostage. In “The Expanding Field,” Rogoff wrote about what has been a deceptive expansion of the art and culture production fields in the neoliberal era:

“The dominance of neoliberal models of work that valorize hyperproduction has meant that the demand is not simply to produce work but also to find ways of funding it, to build up the environments that sustain it, to develop the discursive frames that open it up to other discussions, to endlessly network it with other work or other structures to expand its reach and seemingly give it additional credit for broader impact. . . . The problem with this infinitely expandable model is that it promises no change whatsoever, simply expansion and inflation.”3

For Rogoff, challenging neoliberal enclosures requires continued experimentation with alternatives that may include construction technics, aesthetics, and representation, and engagement with various constituents—individuals, collectives, and institutions. Where is it possible to find space for free exploration in a world4 closed off by neoliberalism and hegemony, and composed of—and trapped inside—its history? How can we engage in practices that allow for testing ideas that might not have a quantifiable outcome? Can we build knowledge institutions that nourish an engagement with diverse constituents, including the marginalized and those that have no obvious representation? Or a pedagogy that fosters a deep understanding of the places and the ecologies we inhabit and design?

II. Tools: Handbooks and Manuals

In 2015, I visited then-93-year-old Yona Friedman in Paris. Friedman studied architecture in Hungary and Israel. Having witnessed the devastation of the world wars, he dedicated much of his life to improving lives by sharing what he called his “technical skills” through computer programming, animation, teaching, writing, and large-scale and participatory installations. His oeuvre, which was produced outside the conventional realm of architecture, found points of intersection with various United Nations agencies and the art world.

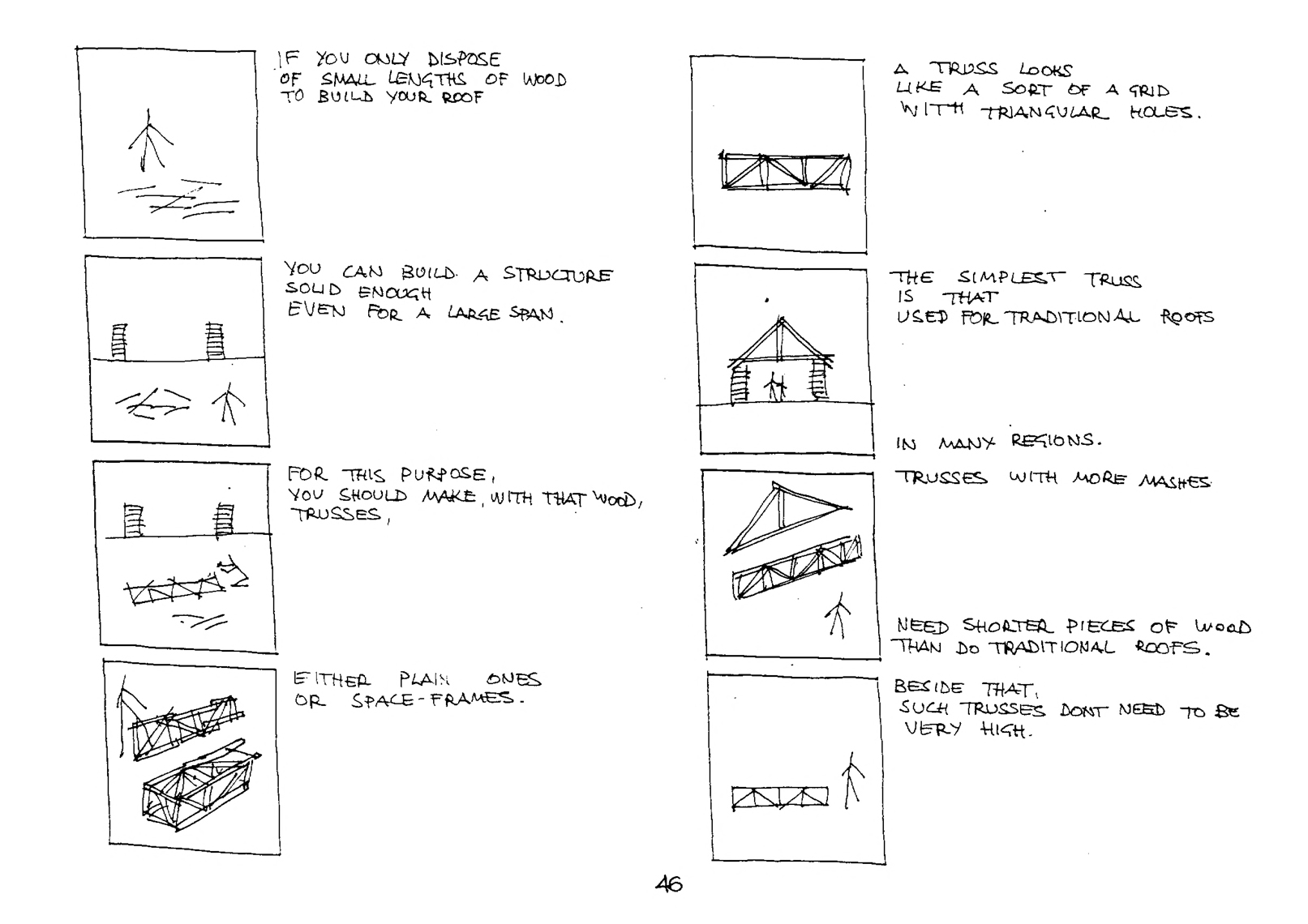

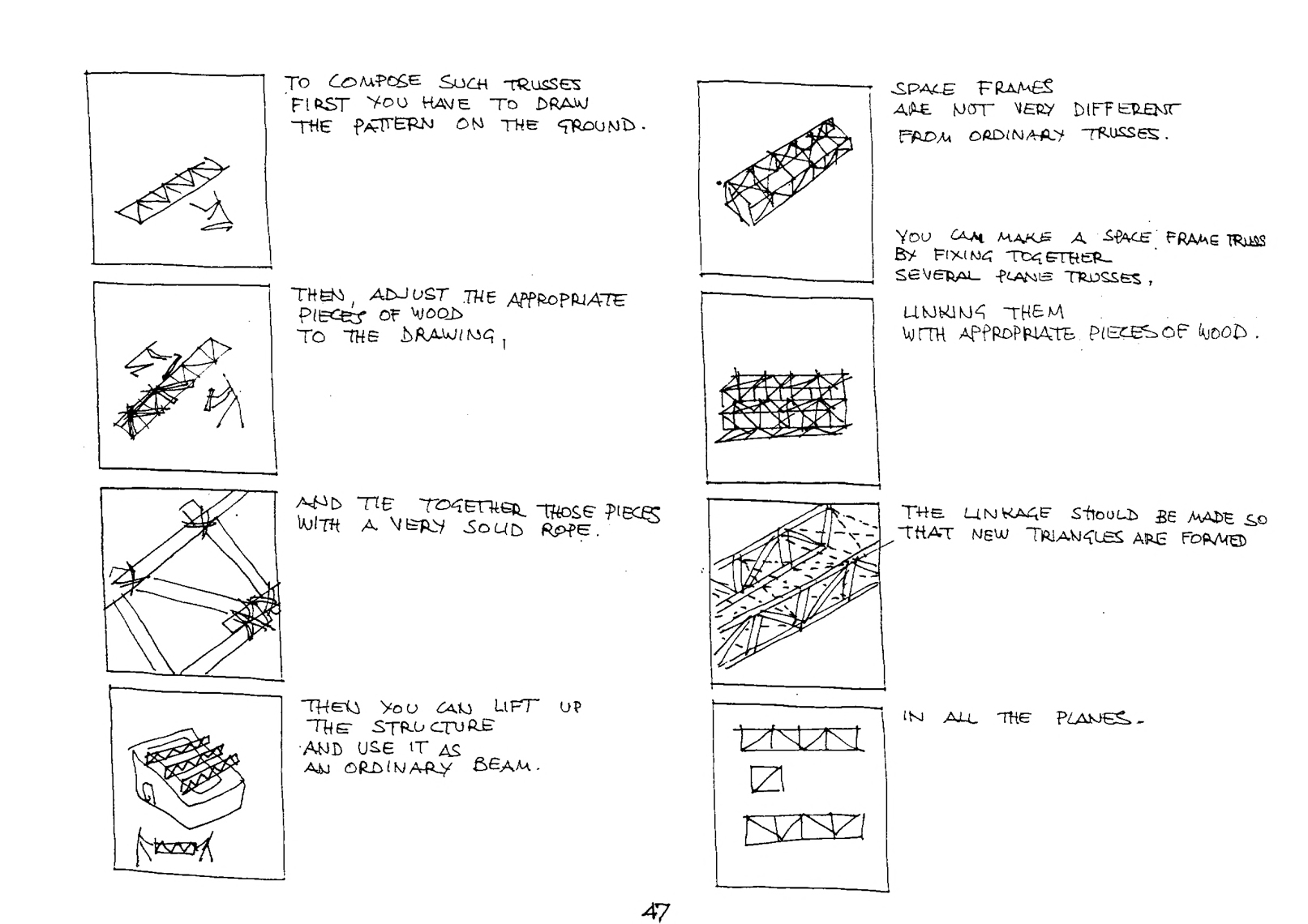

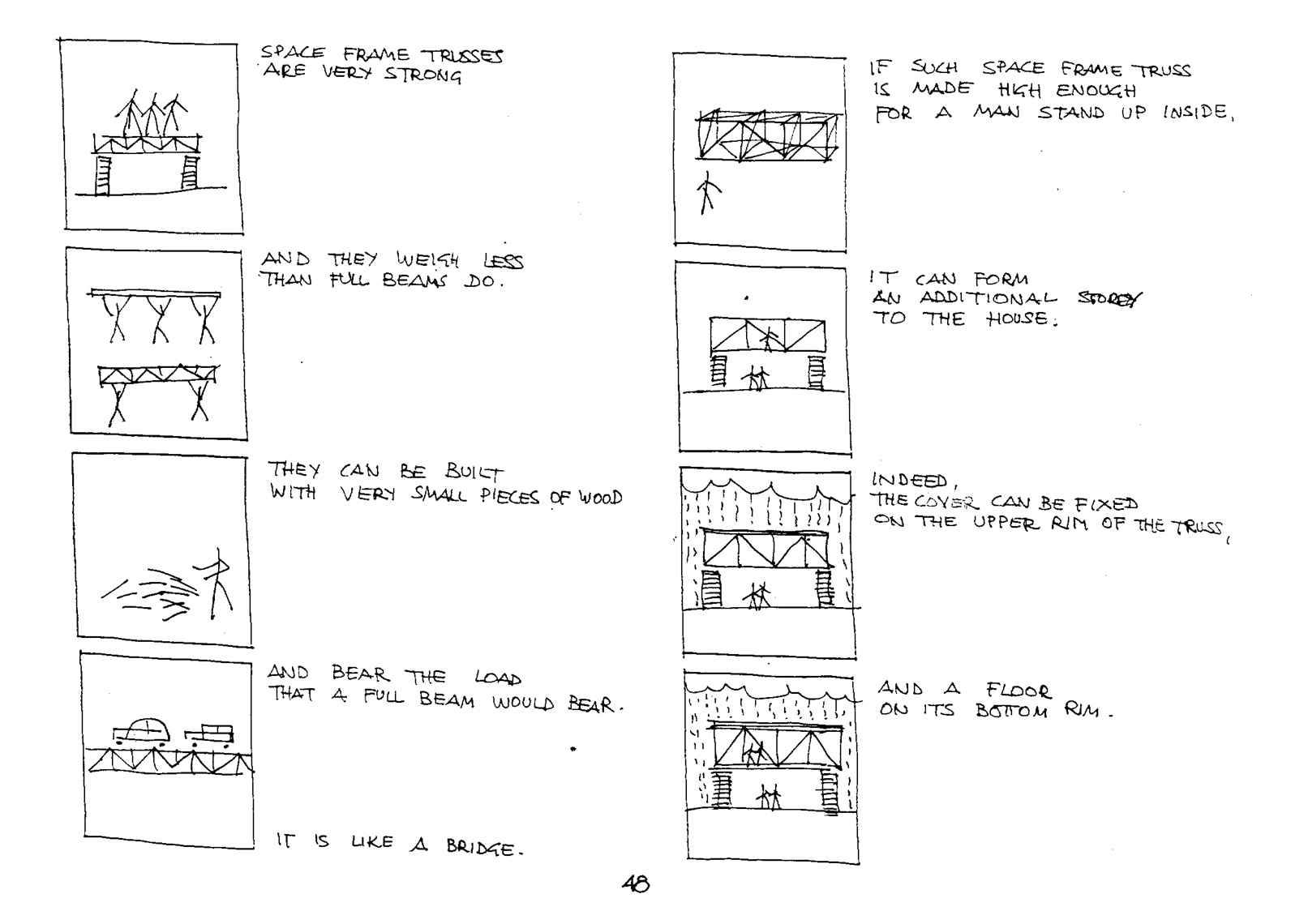

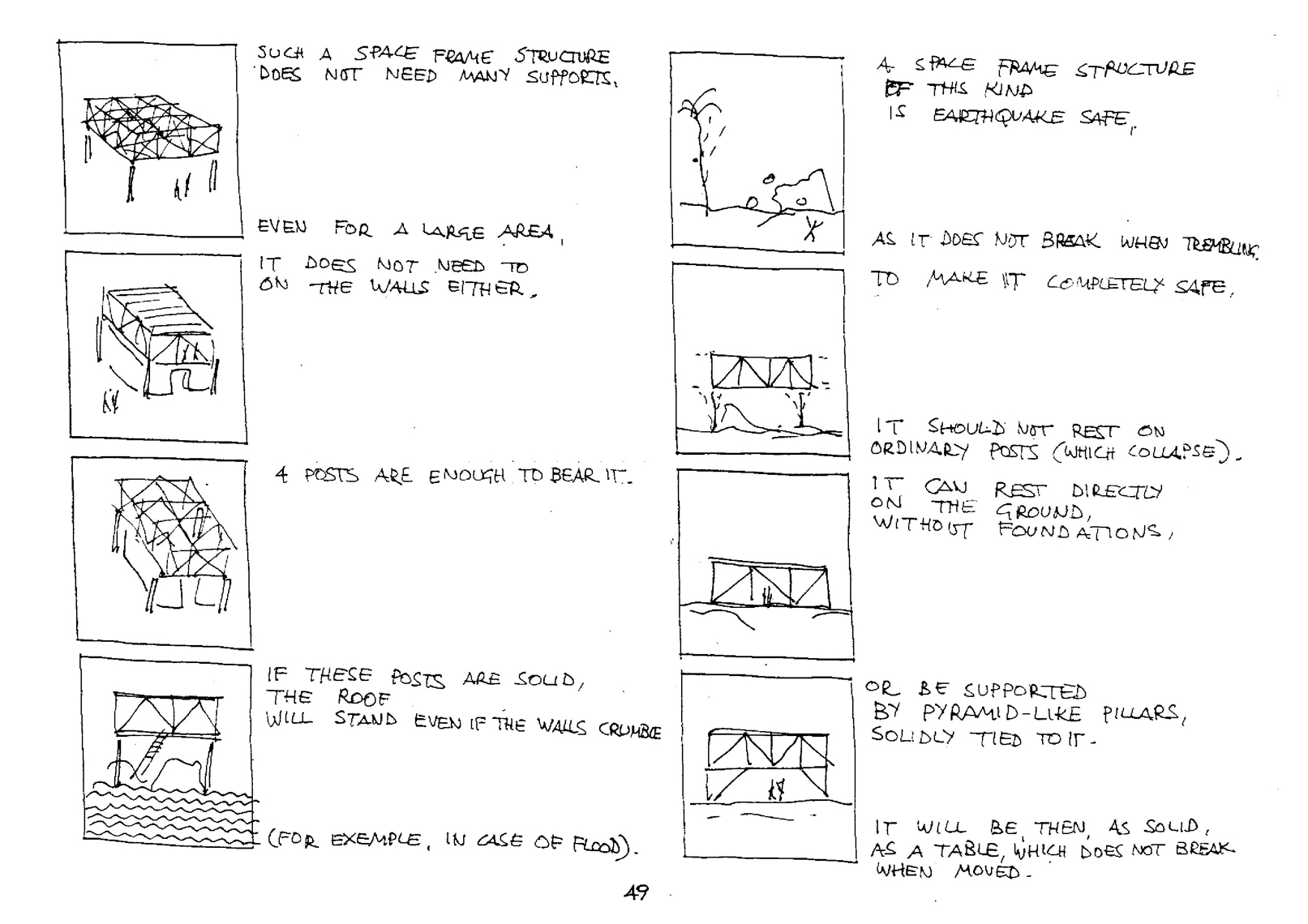

Friedman’s response to our globalizing world was the creation of manuals and protocols that provided essential training and shared construction and design technics through simple instructions and illustrations. These manuals were concerned with the lack of access to resources, growing disparities between rich and poor, and the environmental devastation caused by industrialization, war, and a globally expanding arsenal of nuclear weapons.5

Take, for example, Roofs. Produced in 1991 in collaboration with the UN Communication Centre of Scientific Knowledge for Self-Reliance, the manual primarily addressed the lack of shelter among people with the lowest levels of income in India.6 Friedman argued that everyone should be able to afford a house through cash purchase or self-construction. A proponent of nonextractive architecture, he believed that houses need to be built of local, regenerative materials that carry minimal environmental effects.

In his manuals, Friedman emphasized the importance of self-reliance and argued that housing projects must allow continuous access to basic needs including water, clean air, renewable energy, and regenerative food production through unsophisticated means like cisterns and windows. His approach rejects the use of supply chains that move materials worldwide and that push up housing costs, contribute significant carbon emissions, and cause environmental degradation. Friedman’s manuals are still relevant, especially now, at a time when the increased use of housing as a financial investment has created an unprecedented housing crisis. In 2021, in the US alone, more than half a million people7 were unhoused and deprived of a basic human right.8

While Roofs specifically addressed the housing crisis among India’s lowest caste, Friedman’s solutions have environmental, social, and cultural benefits for all strata. His manuals challenge the architecture field’s complicity in pricing millions of residents out of their cities, communities, and homes. Roofs is an act of radical care by design. It includes care for oneself, care for others, and care for the environment, and it provides a space of hope in precarious times. During our conversation in Paris, Friedman explained that the art world and its galleries, exhibitions, festivals, and socially engaged outdoor installations allowed him the freedom to try new ideas and to develop prototypes that were not supported by the architecture profession and its marketplace.

III. First Intersection: Platforms and Agency

The search for spaces of experimentation that give agency and support to the disenfranchised was the primary reason I cofounded FAST.9 I was frustrated by the architecture field’s enabling of spatial and environmental injustice. Like Yona Friedman, I studied architecture at the Technion. Environmental racism, or an environment of racism, was not only an identifiable feature of Israel’s spatial landscape, it was prominently present in the school. Our library contained strategic plans and masterplans that provided the briefs and framework for architectural production, spatializing national ideology, and giving form to segregation. The spaces we were taught to design were intended to prevent Palestinian individuals and communities from thriving. Segregation by design, however, is not an Israeli invention. It can be found everywhere. In the US, spatial manipulations like redlining10 and other creative uses of standards and regulations serve to perpetuate segregation by income or race. It was not only frustration that led me to cofound FAST, however. It was also hope. If design can enable transformation, it should have the power to promote social and environmental justice.

FAST’s first project—described in the book Village: One Land Two Systems and Platform Paradise—was aimed at supporting the then-unrecognized village of Ein Hawd. The forcibly displaced community of Ein Hawd needed to negotiate their civic rights with the Israeli planning authorities, including securing access to public services and lifting the threat of demolition of their homes. For this project, we borrowed tools from the architecture and art fields, such as the architecture competition, the exhibition, the symposium, and the magazine. We had ongoing conversations with the inhabitants; conducted field research; examined local strategic plans, masterplans, and policy documents; and engaged with policymakers and politicians. Eventually, we translated the desires of the community into a masterplan with which they could begin a negotiation on a more equal footing with the local planning authorities.

IV. Second Intersection: Art

The original village of Ein Hawd was confiscated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, also known as the Naqba—the Palestinian catastrophe. During that war, hundreds of Palestinian localities were seized by the Israeli army, and most of them were erased in the following decade. About a million Palestinians became refugees and were taken into refugee camps under the auspices of international aid organizations. The camps exist to this day and now house descendants of those original refugees. After the 1948 war, Israeli architects designed cities, agricultural settlements, industrial centers, and a range of infrastructures across the country—transforming Palestine into Israel while blurring the traces of its former life. Ein Hawd was seized and given to a group of avant-garde artists led by the founder of the Dada movement, Marcel Janco.

The village became suspended in time, capturing this period of transformation while highlighting the role of the creative fields in producing this change. I came to know it intimately during my architecture studies through my friendship with Muhammad Abu el-Hayja and his family. Muhammad was from the new Ein Hawd, the village his grandfather decided to erect after realizing that his community and family would not be allowed to return to their homes. When Ein Hawd was confiscated, its residents were all turned into trespassers overnight, and they had no choice but to slowly build a village on agricultural land they owned, a kilometer away. While building new shelters for themselves, they witnessed how their original homes were converted into an art commune by Janco and others.

The artists that settled in the confiscated homes in the original Ein Hawd were liberated from any responsibility or obligation to justify themselves. As a result, they renamed the space and fabricated a new village history. They transformed homes into galleries and studios, fields into performance spaces, and cemeteries into sculpture gardens. They connected the village’s old stone structures, designed and constructed by the best Palestinian masons in the region, to biblical tales of their own ancestral claims. This space of experimentation occurred under the patronage of a rising Israeli hegemony. During the first decades after the international recognition of Israel, these artists’ work led to an intensive process of cultural production that set the ethos of an emerging society.

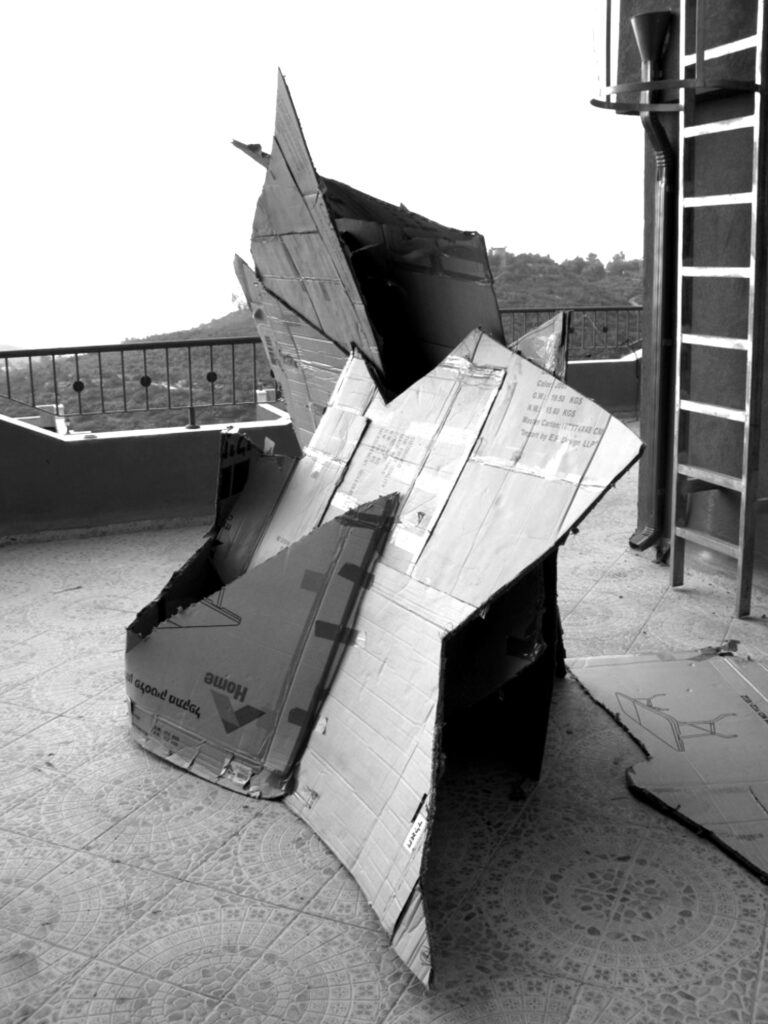

Yona Friedman designed an installation for one of the events FAST organized together with this displaced Palestinian community. Following his advocacy for simple architecture that can be produced by anyone and at any budget, he sketched Merzstrukturen, a handbook for Ein Hawd’s community. In an expanding field of art and cultural production, “one can no longer be content with taking positions within a given definition; one has to stretch and twist itself inside out to become significant again,” according to Rogoff,11 and claim agency and act regardless of external challenges and constraints. Friedman’s project for Ein Hawd was part of his study into irregular structures shaped by infinite relationships between different social groups in everyday life. He believed that precarious living conditions, like displacement, can modify the built environment and create realms of unsettled planning. Such precarity, he argued, can lead to the spontaneous birth of architecture and the emergence of new conditions of life.

Merzstrukturen: Building one’s individual home out of randomly found components assembled and installed during our project One Land Two Systems and Platform Paradise in Ein Hawd. The installation is on a balcony of a private house in the village overlooking the artist colony, the Carmel Mountain, and the Mediterranean Sea, 2014.

V. Third Intersection: Engagement with Institutions

FAST’s project with the Ein Hawd community put our practice at the intersection of architecture, urban planning, art, and activism. One of our subsequent projects was BLUE: Architecture of UN Peacekeeping Missions, focusing on how the UN’s missions impact cities, communities, and the environment. After analyzing the organization’s peacekeeping operations—the UN’s most extensive missions in terms of budget, mandate, number of personnel, and material footprint—we developed a policy matrix that highlighted the importance of self-reliance and emphasized the need for local empowerment in the production of regenerative food, safe water, and renewable energy systems. Instead of relying on the perpetual inflation and dependency caused by global supply chains, we advocated for a situated approach that strengthens local communities. We studied conflict-affected cities and communities, and we analyzed and made visible the role of institutions like the UN in perpetuating some of the problems it meant to solve.

Over the past 10 years, we’ve not only proposed designs, we’ve also attempted to generate systemic change by intervening in institutional processes. Incorporating lobbying and experimental collaborations—across fields including international relations, waste management, military engineering, and human rights law—has enabled us to highlight and expand these possibilities. FAST’s comprehensive studies have been adopted by various UN agencies, nation-states that contribute to humanitarian and peacekeeping missions and those that host them, and policymakers that use our work to promote social and environmental justice. Elements of our proposed recommendation were also adopted by the UN Security Council.

VI. Fourth Intersection: Archives and other Formats

In the last part of “The Expanding Field,” Rogoff critiques the archive as an infrastructure of knowledge production while simultaneously intersecting it with the notion of contemporaneity. She describes it as “a series of affinities with contemporary urgencies and the ability to access them in our work.”12 The archive plays a vital role in all of FAST’s projects as a critical space of investigation, reflection, and intervention that necessitates creative experimentation.

Subverting the Atlas

Atlas of the Conflict: Israel-Palestine maps the emergence of Israel and the disappearance of Palestine over the past century. It challenges the atlas as a form of exclusive representation that, on the one hand, strategically surveys land and population for the sake of extraction of material resources, labor, and taxes, and on the other, argues for territorial and economic expansion and growth. Analyzing Israel’s formal atlases through this lens allowed us to identify evidence of colonization and dispossession. Atlas of the Conflict juxtaposes two narratives—one collected from Israeli national and official archives and the other gathered through engagement with human rights organizations and community grassroots groups. By redrawing these findings at the same scale and as parallel histories, two contingent realities emerged: one being built and commemorated and the other being destroyed and forgotten. Our atlas uses the archive as a space for interrogation and resistance, but it literally expands the archive as well.

Tablecloth as an Archive

Border Ecologies and the Gaza Strip is a research, engagement, and representation project that FAST took on in collaboration with a small community of Gazan farmers living along one of the world’s most militarized and violent borders. While their livelihood is subjected to a range of political and geopolitical violence, their stories and history are absent from official archives and the protocols that dictate how such official knowledge is produced and preserved. For this project, we designed a seven-and-a-half-meter by one-and-a-half-meter tablecloth that overlaps multiple timelines of global, regional, national, and local events that impacted the farm and the farmers’ livelihood. We also use illustrations, keywords, and QR codes that reveal stories we collected from farmers about their daily lives. The tablecloth can be seen as a collaborative, relational archive between the farmers and us. The tablecloth, as an artifact, was produced in collaboration with the master weaver of the Tilburg Textile Museum in the Netherlands. The stories of this Gazan community are now preserved on a tablecloth in a Dutch national archive.

VII. Inflation Expanded: Multihyphenate and Hope

The multihyphenate practitioner being explored in this issue of Harvard Design Magazine takes on the fluid and continuously expanding role of the architect–curator–art director–furniture designer-theorist as a reaction to overpowering economic forces. In response, Rogoff may argue that “the problem with this infinitely expandable model is that it promises no change whatsoever, simply expansion and inflation.”

But for FAST, the questions we ask and the complex realities we engage with have no simple answers. These questions instigate open-ended processes contingent on extensive research, comprehensive engagement strategy, and collaboration. We must be multihyphenates in order to effect change, even if the change is incremental. Unfortunately, this mode of practice—at the intersection of art, spatial design, and activism—receives very little support from a world closed by a neoliberalism that only rewards efficiency and productivity that contribute to measurable economic growth.

We must keep looking for unexpected environments of experimentation and

empowerment. We need to cultivate spaces that bring forward social and cultural values and ethics that exist outside the extractive logic of neoliberalism and hegemony and their respective devastating effects on our lives and planet. As Yona Friedman argued, precarious times modify the built environment and the infinite relationships between different social groups and their everyday life. Times of uncertainty and precarity may also be conceived as times of hope, as they can give birth to a new kind of spontaneous architecture and new conditions of life that nourish care—self-care, care for others, and care for the environment.

1 George Monbiot, “Neoliberalism—the ideology at the root of all our problems,” The Guardian, April 15, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/15/neoliberalism-ideology-problem-george-monbiot.

2 Reinhold Martin, Jacob Moore, and Susanne Schindler, The Art of Inequality: Architecture, Housing, and Real Estate (New York: The Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture, Columbia University, 2015).

3 Irit Rogoff, “The Expanding Field,” in The Curatorial: A Philosophy of Curating, ed. Jean-Paul Martinon (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 41–48.

4 Stuart Walton, “Theory from the Ruins,” Aeon, May 31, 2017, https://aeon.co/essays/how-the-frankfurt-school-diagnosed-the-ills-of-western-civilisation.

5 Yona Friedman, Energy and Self-Reliance Handbook, 1986.

6 Yona Friedman, Roofs, https://archive.org/details/Roofs-PartOne-English-YonaFriedman.

7 “HUD 2021 Annual Homeless Assessment Report Part 1,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, https://www.hud.gov/press/press_releases_media_advisories/hud_no_22_022.

8 Housing is a right, not a commodity. It is the basis of stability and security—a place to live in peace and dignity.

9 In 2005, I registered FAST in the Netherlands as an NGO with the support of Alwine van Heemstra, a documentary filmmaker and transformation coach; Michiel Schwarz, an independent thinker, curator, and consultant interested in how the future is shaped by culture; and Willem Velthoven, who is trained in visual communications and art history. Velthoven cofounded Mediamatic, an Amsterdam-based experimental art and design center that inspires and supports FAST’s work. So far, all our projects are funded by public cultural agencies that encourage exploratory art and design practices.

10 Redlining in loan distribution meant that mixed-race or all-Black neighborhoods were considered high-risk in governmentally insured mortgage programs, which effectively meant that no loans were available in those areas. See Martin, Moore, and Schindle, The Art of Inequality: Architecture, Housing, and Real Estate.

11 Rogoff, “The Expanding Field,” 41–48.

12 Ibid.