Too Much: The Grand Canyon(s)

There are too many Grand Canyons. There is the place itself and its staggering geography—the rims, the river in the Inner Gorge, the maze of side canyons, mesas, plateaus, forests, arroyos, vegetation and wildlife, and all those hoodoos, columns and spires (so-called by 19th-century devotees of the Church of the Wilderness). There is the no-nonsense (and topographically nonsensical) governmental gridding of ungriddable lands as the frontier fell away. There are the variously perceived canyons through which flow the never-ending verbiage that attempts but never succeeds in seeing, let alone describing, this sight of sights. And at a deeper level, there are the interpreted canyons, the contested canyons. From these emerge our individual and collective psyches, reflected in the geographies of national history and personal experience. The abysses are epitomized by fundamentally divergent views of place and nature expressed by the Canyon’s Native peoples and by the ruling ethics of the National Park and Forest Services, themselves often at loggerheads.1 The Grand Canyon’s macro-microcosmic multiplicity staggers retina and rhetoric.

“Without doubt our epoch . . . prefers the image to the thing, the copy to the original, the representation to the reality, appearance to being. . . . What is sacred for it is only illusion.” Thus spake proto-postmodernist Ludwig Feuerbach, who died in 1872. Situationist Guy Debord used this quote to kick off his classic Society of the Spectacle.2 Today Debord’s theories, mostly cleansed of Marxism, have recaptured attention, although they are rarely applied to landscape. Yet the Grand Canyon is a “natural” candidate for spectacle status, touted as one of “nature’s” crowning achievements, and therefore not to be blamed on civilization or the lack thereof. Debord taught us that our minds and eyes are trained by hegemony, Hollywood, et al., to treat spectacles as ahistorical objects. “The spectacle,” he wrote, “as the present social organization of the paralysis of history and memory, of the abandonment of history built on the foundation of historical time, is the false consciousness of time.”3

Picking up and running with this ball, postmodern academic criticism has taught us, ad nauseam, that the whole world is packaged for us, that nature is no exception, that we never see what is before us without an invisible frame courtesy of the mass media or even of great art and literature. We are, in other words, virtually forbidden to experience anything directly. Once we are persuaded by disaffected scholars to see all of nature as a sentimentalized theme park, a stage set, a backdrop, we are bereft of spiritual possibility, optimism, action. Debord predicted this misuse of his theory, warning that “undoubtedly the critical concept of spectacle can also be vulgarized into some kind of hollow formula of sociologico-political rhetoric to explain and abstractly denounce everything, and thus serve as a defense of the spectacular system. For an effective destruction of the society of the spectacle, what is needed is men [sic] putting a practical force into action.”4

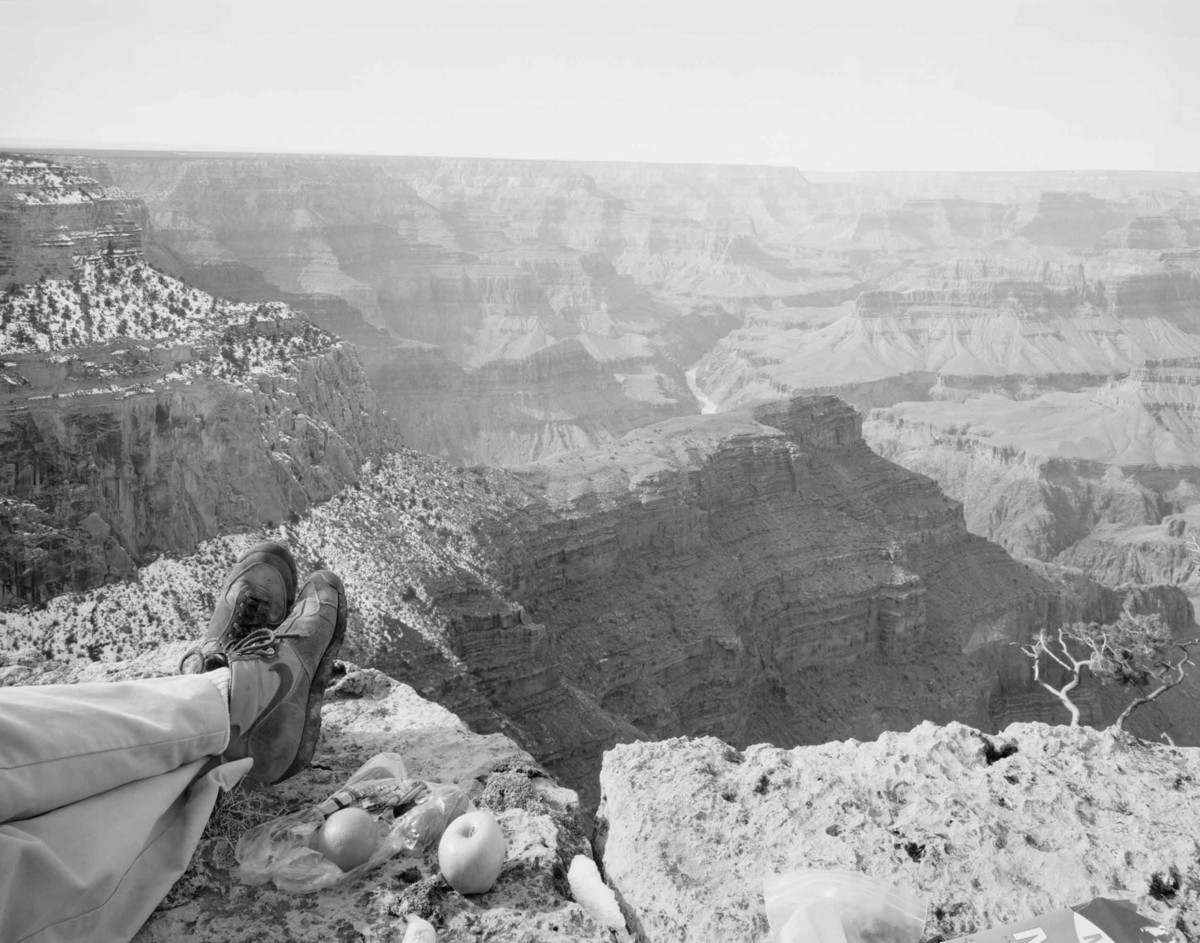

Actually entering the Canyon, even in the constant company of twenty other people, as I did recently, can be an antidote both to illusion and cynicism; it can rip off the packaging and splinter the frame. (The ghosts remain: the package ghost—the experience we expect to have; the frame ghost—the pictures we expected to take.) But below, after the descent, down inside the canyons, the event is harder to cope with. Large and small vie for our attention, every rock, every cliff competes every minute with another, with “the view” ahead, the view behind, up and around, with the cacti and wildflowers, the despairing gestures of the red-blossoming ocatillo’s skinny arms, with the harsh and melodious calls of ravens, canyon wrens, and gulls. Rough ground underfoot, edging along chasms, wading into waterfalls, soaking in grotto pools, clambering on slippery shelves, stumbling through rocky streams and over parched boulders. And above and below it all, day and night, the roar of rapids, burbling in the deep, surfacing in force, raising waves that can reach twelve feet at the infamous Lava and Crystal falls.

The real human construction is finally a sense of individual responsibility, although one component of any creative response is confrontation with previously imposed constructions. It’s all too easy to drift lazily into fashionable preconceptions formed by others and find our fresh eyes filtered, our imaginations blocked. By allowing this to happen, we deprive ourselves of the kind of “authenticity” we think we are after. Yet as soon as we seek authenticity, we are nudged by education, sophistication, and modernity into anxiety about how much we are “influenced.” Illusion is replaced by memory, equally susceptible to intellectual fashion.

Until I went past the rims, leapt over the edge, so to speak, the Canyon didn’t interest me much beyond its obdurate identity as a spectacle, a melodramatic aesthetic, and an academic cliché. While I was on the river, I had not an “original” thought, and barely a thought at all. I was lulled by being guided. I had no maps, although I love them. I didn’t buy the long thin fold-out with every rapid marked and intriguing tidbits of history and science in the margins. Somewhere in my mind, this had already been ordained as a mapless voyage. I had been asked to go along at the last minute and dropped everything to do it. For once, I hadn’t done my homework. I didn’t know where we were putting in or taking out. I didn’t even know if it was a motorized or paddling or rowing trip. All I had time to think about was whether I had any nylon clothes that would dry quickly (only a leopard skin pajama top that I never had the guts to wear) and whether my bent tentpole would hold up (it didn’t). It was in many ways the ideal way to take the plunge. I was treading water.

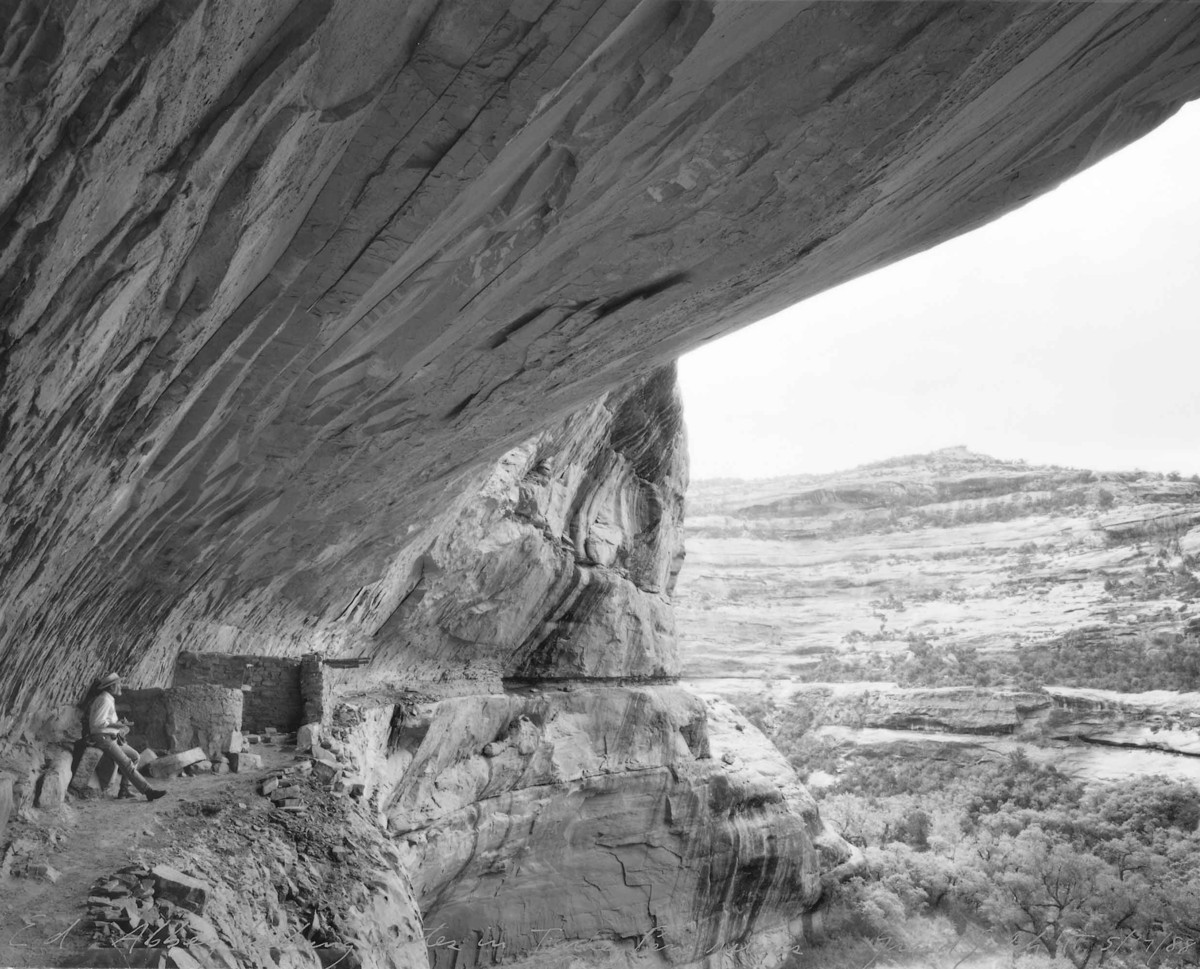

The American West is full of stunning canyons, secreted among the flat grasslands and rolling high deserts, come upon with breathtaking suddenness at their brinks, glimpses into contrasting worlds of red rock, green trees, ruins, wildlife, and water. The Grand Canyon is layeredness taken past the equation, backdrops that flatten the imposing masses, but never stop coming. It is “ageless” (not reduceable to human scale, not easily comprehended), and constantly changing. “No matter how far you have wandered hitherto,” wrote John Muir, “or how many famous gorges and valleys you have seen, this one, the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, will seem as novel to you, as unearthly in the color and grandeur and quantity of its architecture, as if you have found it after death, on some other star.”5

Human construction of experience, fragmentation into spectacle, is a weapon, armor, or refuge from the terrible possibilities of chaos, of unconstructed, unimagined experience. In retrospect, the gap between general and specific is what catches my imagination. It seems to offer a bridge between theory and practice. Action is an antidote to the indescribable. “I find that I tell more about what we did than what we saw,” wrote Marion Smith, after a Grand Canyon raft trip with riverwoman Georgie White Clark. “To describe the scenery is quite beyond me and almost, I believe, beyond the camera. The distances up above, way ahead, and far behind, are so vast, the great canyon so alive somehow, that its true scale and impact can only be approximated even with motion pictures. One must go there to know it.”6 The relations between doing and seeing, action and vision, construction and perception, lie at the core of the Grand Canyon experience—or experiences.

In cultural terms, landscapes only come alive, in fact only become landscapes, when they are focused upon, when they become specific, when humans begin to interpret them, like the hoary tree falling in the forest. A landscape experienced as generalization, the frequent fate of the Grand Canyon, is not itself. As Paul Shepheard writes, “. . . although everywhere the world is the same as itself, landscape is nowhere the same as itself: you have to show landscape by example, because as a subject it won’t reduce to fundamentals; it won’t trivialize. . . . Geography is global. Chorography is regional. Topography is local.”7 You can lose your way in the specific because there are too many paths, too many featureless thickets, too many options, too many box canyons and shelves with no exit. You can also lose your way in the general, because there is no path.

The Grand Canyon as human construction, or cliché, is familiar to everyone. Say the magic words and a single image appears in the mind’s eye—the view from the North Rim. It is an image formed by images for well over a century, an image that has survived fluctuating conceptions of nature and our responsibilities to it. Before the invention of halftones, the public saw the Canyon through the eyes of engravers taking liberties with photographic originals, exaggerating heights and grades. Then came color—the railroad propaganda and the calendars, red purple brown gold orange and blue cliffs layered by light and mists into infinity—beautiful images, and boring in their beauty.

It has been argued that there is no such thing as wilderness. It has been argued, equally viably, that there is. However our notions of wilderness may vary, and have varied culturally over the recordable centuries, I think most of us can judge when we are within it, or within our own notion of what it should be, or approaching that state of mind. The level of uneasiness increases, matched by the level of exhilaration. Wilderness, even as a generalization, is not a place you can look at or even into. Standing on a rim, you may say you have been at the Grand Canyon, you may even say you have seen the Grand Canyon, but without the descent (and all it implies), you have not been in the Grand Canyon. Opening up the Wilderness, they called it in frontier days, sexual innuendoes intact—as in virgin land, rape of the land.

William Cronon says that in the 18th century there was a “sense of wilderness as a landscape where the supernatural lay just beneath the surface. . . . God was on the mountaintop, in the chasm, in the waterfall, in the thundercloud, in the rainbow, in the sunset. One has only to think of the sites that Americans chose for their first national parks—Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Rainier, Zion—to realize that virtually all of them fit one or more of these catagories.”8 (God did not visit the swamps and the grasslands until decades later.) In the 19th century, however, Americans found God wanting in a few details, and took over the job for themselves. In the 20th century we lived out the techno fantasies and have lived to regret some of them. At millennium’s end, the Grand Canyon is as often as not valued for its “spiritual” gifts. We have come almost full circle.

There has always been internal manipulation of landscape and there has always been external aesthetic control. The excesses to which contemporary agonizing over intellectual “constructions” has gone are examined by Jon Margolis, writing in High Country News.9 He cites attacks on wilderness legislation not only from the political right but also from the left: “Well, actually, they’re from the post-modernists, which is not the same thing. It’s not that these critics are against wilderness, exactly; they’re just disturbed by the idea of wilderness.” Then, with grudging approval, he quotes Cronon saying that the real problem lies not in wilderness per se but in “what we ourselves mean when we use that label.” After making wholly justified fun of some incomprehensible academic jargon on the subject, Margolis finally concedes that “having to respond to a more complex critique has forced pro-wilderness troops to sharpen their scientific, cultural and political case.” Ideally, these critiques would themselves be couched in collaboration with conservationists, lending themselves to a clearer “reading” of landscapes like the Grand Canyon.

An understanding of the society of the spectacle is useful, and a clear sense of how we are manipulated by representation is a necessary tool for surviving postmodern life, pointing up aspects of the contemporary experience even as we deny that such a thing can be unmediated. But knowledge to the extreme can also be destructive. Exaggerated skepticism (borderline cynicism) can leach away our innocence, smooth off the rough edges that allow our gears to fit into those of wild places, that allow us to understand our familiarity with what we persist in calling nature. When we forget to include ourselves, we are cut off from our surroundings and our cohabitants. No place lends itself more easily to these affectations than the Grand Canyon(s), especially the one conceived from the rims. Here are places that are “inhuman”—godlike or demonic. We can’t reason with such places, our culture seems to imply, so we’d better try to overpower them. Vulnerability is a thorn in our flesh. Every tale of flash floods, falls from crumbling cliffs, lightning strikes, drownings, heatstrokes, summer hailstorms, unbearable heat and cold, has its moral, and calls out for Control.

Damming great rivers is an unsubtle way to reconstruct their meanings. The watering of the arid west—a remarkable and often repellent story brilliantly told by Donald Worster (Rivers of Empire) and Marc Reisner (Cadillac Desert)—includes the damming of Glen Canyon and the irony of naming the resultant Lake Powell (a.k.a. Lake Foul) after the man who warned that the waters of the arid west should remain in the hands of locals who understood it. And as if Lake Powell were not enough, as if the Canyon had to be punished for still thumbing its nose at those who would dominate it, plans continued to be made to dam the Grand Canyon itself. It was, in fact, saved by the tragedy of Lake Powell and by the deflection of a dam at Echo Park in Dinosaur National Park. The proposed dams were stopped by a public shift in attitude away from water exploitation and toward wilderness protection.10 This happened in the 1950s, when the Canyon underwent “an immense cultural metamorphosis,” becoming again, though the imperial overtones this time were somewhat muted, part of a national “geography of hope.”11

When conservationist David Brower said, “If we can’t save the Grand Canyon, what the hell can we save?”12 he acknowledged the necessity of publicity, a ploy that often backfires. Singer-songwriter Katie Lee noted that “the more people you get to fight for the rivers, the more people you have to take to the rivers, thereby ruining them in order to save them from destruction.”13 The millions of tourists who visit the Grand Canyon each year, myself included, go there for a relatively safe experience of risk, a temporary sense of freedom within the bounds of reason and security. These days the “spiritual” is also much in demand. And who can escape it in the Grand Canyon? The place produces stories not merely of action as the macho adventure magazines would have it, but also of interaction.

With a certain logic of contrast (and incomprehensible overload), tourists often take a package tour combining two disparate spectacles: the Grand Canyon and Las Vegas—gambles of a different nature. “Capitalist production,” wrote Debord, “has unified space, which is no longer bounded by external societies. This unification is at the same time an extensive and intensive process of banalization. . . . A byproduct of the circulation of commodities, tourism, human circulation considered as consumption, is basically reduced to the leisure of going to see what has become banal. . . . The economic organization of the frequentation of different places is already in itself the guarantee of their equivalence. The same modernization which has removed time from travel has also removed it from the reality of space.”14

Like tourists, contemporary writers must be wary of the “superficial mysticism, sentimentalism, and loss of critical faculties” which are an occupational hazard when we are connecting with something larger than ourselves. Is Thoreau’s “vital and intense sense of connection to nature” possible in a skeptical postmodern era?15 Anyone who can avoid a certain romanticism in the Grand Canyon is probably hopeless. John Wesley Powell, a remarkably tough guy, wrote, “A mountain covered by pure snow 10,000 feet high has but little more effect on the imagination than a mountain of snow 1,000 feet high—it is but more of the same thing; but a facade of seven systems of rock has its sublimity multiplied sevenfold.”16 Are we no longer allowed such responses because we have learned their transparency? Can’t we also maintain their transcendency? The hyperbole resorted to by Muir, Powell, and endless others is normal. The place itself is off the charts. It resists casual treatment even when reduced to scientific “truths.” We know that the boring and astounding calendar picture is not just a geology textbook. The Grand Canyon’s all-consuming scale leaves little energy for facile consumption. Writers like to mull over palimpsests, but enough is enough. The extravagantly layered strata flaunt their dangerous illegibility, so laden with efforts at legibility—with artifice and generalization—over the last century that they threaten to take up all the space our mythology has allotted to the Grand Canyon. They interfere with the first-hand experiences we value—so-called authenticity.

Our contemporary models, although many, offer little help in coping with the (artificial) divide between subjective awe and objective reining in of emotion. Finally, it is the “Thoreau of the West,” Edward Abbey—macho, bigoted, intolerant, arrogant, and irritating as he often was—who most convincingly found words for his passion for the canyonlands, who found a language that combined poetry and outrage. Sometimes I hate to like Abbey’s writing so much. While he can be as sentimental and rhetorical as the next applicant, he was rarely “soft-headed,” and frequently, almost involuntarily, lyrical. In his essay “Down the River with Henry Thoreau,” he insisted that the Sage of Concord “becomes more significant with each passing decade. The deeper our United States sinks into industrialism, urbanism, militarism—with the rest of the world doing its best to emulate America—the more poignant, strong and appealing becomes Thoreau’s demand for the right of every man, every woman, every child, every dog, every tree, every snail darter, every lousewort, every living thing, to live its own life in its own way at its own pace in its own square mile of home. Or in its own stretch of river. . . . The village crank becomes a world figure. . . . Truth threatens power, now and always.”17 At heart, however “postmodern” (which is a way of coping with modernity as much as it is a theory), however distrustful of words like “truth” we may have become, I believe that most of us feel as Abbey does, although few go on to give it time or energy.

Before techno bliss, simulated landscapes were created as photo backdrops, dioramas, and historical “machines,” like Thomas Moran’s late and very large paintings of the Grand Canyon, shown as autonomous “exhibits” rather than as parts of an exhibition. “Topography in art is valueless,” said the artist.18 “The Canyon’s rim was American art’s greatest gallery and its greatest pulpit,” writes Stephen Pyne, author of the crisply brilliant compendium How the Canyon Became Grand. There have been heroic attempts to depict the Canyon by painters and photographers (not sculptors, because it’s being done already, too well, right there before our very eyes). They are all men—Moran, H.B. Mollhausen, John Hillers, Timothy O’Sullivan, William Henry Holmes, Carl Oscar Borg, Gunnar Widforss, and finally Eliot Porter, who tried to resacralize the place in the 1960s in the face of more dam proposals. Eventually, progressive artists gave up on the Grand Canyon, which had become a “celebrity . . . a museum piece . . . culturally moribund,” and therefore vulnerable to exploitation.19 Despite the attempts of a few bold artists (such as Susan Shatter) to represent the canyon, the dry realism now fashionable is as inadequate to the task as modernism itself has proved. Pyne blames the triumph of commercial art on modernism’s disdain for its audience: “High culture had to compete with the purveyors of the Canyon as experience, not simply as idea. . . .”20

Inherent, if invisible, in the Grand Canyon’s apocalyptic image is the consciousness of destruction that Barbara Novak identifies as a mark of 19th-century nature painting. There is a remarkable similarity in the content, if not the style, of aesthetic alarm over the last century. “The axe of civilization is busy with our old forests. . . . What were once the wild and picturesque haunts of the Red Man, and where the wild deer roamed in freedom, are becoming the abodes of commerce and the seats of manufactures. . . .” wrote J.F. Cropsey in 1847.21 Today, the threatening axe of previous centuries has become the still more menacing bulldozer and backhoe, the intruding road has become the helicopter, the specters are now pollution, crowds, and loss of habitat. Chuck Forsman, in his Arrested Rivers series of photorealist paintings that depict the dammed (and damned) rivers of the West, belies the placid, complacent views expected of conventional landscape painting. Janet Culbertson’s poignant canvases of stark, barren landscapes, inhabited only by billboards that are themselves paintings of lost idyllic scenery, give nostalgia pause. Could anyone in the 19th century have imagined how far things would go? Can we imagine the future pictured by Culbertson, where only the image remains?

It has been suggested that designers may be tempted by the “increasing power to control and modify nature.”22 What kind of unprecedented work might they come up with? It gives me the creeps to think about the extreme limits of this proposition. A landscape designer stands on the North Rim, looks outward, downward, like a 19th-century landscape painter with brush poised between palette and canvas. Let’s see, a bit more redwall there . . . take out that awkward parapet here, that boring schist. . . . There now. That’s more like it.

Like what? Like the 19th-century painter’s rendering of the sublime? Like the mid-20th century photographer’s “reality”? Like the conceptual artist’s ironies? Like the publicist’s seduction and hyperbole? Into what chink in those towering, spotlit walls can we fit our own “views”? What next? A plastic Grand Canyon theme park to replace the one dammed and devastated within the church of progress?

The graffiti is on the redwall, so to speak. A recent press release from a New York gallery describes the work of Los Angeles artist Jacci Den Hartog, which “explores the potential of manufactured materials to simulate nature and reconstitute a comparable sublime.” Like the existing Japanese indoor beaches and ski slopes, this makes the mere idea of the human construction of nature look tame. Not quite virtual reality (that’s next) is contemporary artists’ response to postmodern constructionism. Andrea Zittel’s Point of Interest—two giant faux rock outcroppings (concrete over steel)—is the latest and largest in a line of art rocks over the last thirty years or so. (Earlier simulators include artists Reeva Potoff and Grace Wapner, as well as the designers of zoos and pet rocks.) Zittel’s sculpture is, according to the Public Art Fund’s 1999 press release, “a reminder that Central Park itself is a meticulously planned natural environment built for the enjoyment of city-dwellers . . . a playful critique of late-20th-century society’s ‘action adventure’ uses of nature (from extreme mountain climbing to the increasingly popular ‘Eco-Challenge’). . . . Point of Interest serves as a reminder that our perceptions of nature are constantly being reinvented and often reflect the values and ideas of society itself.”

I imagine an exhibition of the millions of amateur snapshots taken in the Grand Canyon. The viewer would walk miles through corridors of canyon impressions, edge to edge, all more or less alike despite widely varying skills and technologies. My own photographs were lousy (artist friends didn’t do all that much better). There was a tremendous disjunction between what was seen and what was represented. This is probably endemic to all photographers of the Grand Canyon, even the almost first and perhaps greatest of them, the methodical genius Timothy O’Sullivan. I managed not to photograph most of my favorite places, a wise, if inadvertant, decision dictated by the fact that my old manual Olympus was wet a lot of the time and the shutter stuck at random. In any case, visual experience is not always about making pictures—in the mind, the canvas, the camera. Pictures were only the end product of an experience that was as kinesthetic as it was visual.

Nor did I make any attempt to remember those 280 miles of amazement. I didn’t “journal” (for a journalist that’s a buswoman’s holiday . . . and it’s not a verb anyway). If I let my mind go blank, I can recall the general and the specific, but not the connections, not the whole. Images resurface—peaceful winding expanses of water more green than blue; the ever-changing rock show and its reflections in the emerald, jade, turquoise, slate, salmon to brown water; the extraordinary panoramas, the wild misty turbulence, the wind, the spray, the permanently wet butt, the high waves and fleeting exhilaration of the rapids, almost dreamlike in their brevity and intensity.

Only when I returned home and started reading Powell, Abbey, the expedition reports, the women’s stories, the historians’ stories, did the constructions loom. The Canyon became realer to me in some ways than when I was there. Now, I realized with a certain sadness, innocent perception was beyond me. Had I read all this to begin with I would have been walking through a much solider looking glass. But ignorance suited me. What could I have known about this place before having been inside it? It’s not for nothing that the river is a preeminent symbol of life. But the narrative flow built into this trip still eludes me. There wasn’t time to consider all that space. We hurried. We had to get on down the river.

Lucy R. Lippard is an art writer. Her latest book is On the Beaten Track.