The New Social Housing

The myth of a Jeffersonian idyll inscribed from our nation’s founding has had a profound and perverted effect on our built environments and notions of success. The idea of an individualistic, self-sufficient, rural landscape distorts policy, planning, and finance systems around housing while blinding us to the resources and subsidies needed to maintain what is, in effect, a false front. The housing crises that have taken many different forms, from urban slums, to urban renewal, to urban displacement, are increasingly visible in the suburbs. Acute in a handful of places, a crisis of affordability, maintenance, land tenure, and economics is infecting more of our single-family landscapes. So what were the initial promises, and what are the current perils, of single-family markets? And how—with different policies, ownership methods, and financing mechanisms—can we shift the prevailing narratives and crushing realities for a growing number of families?

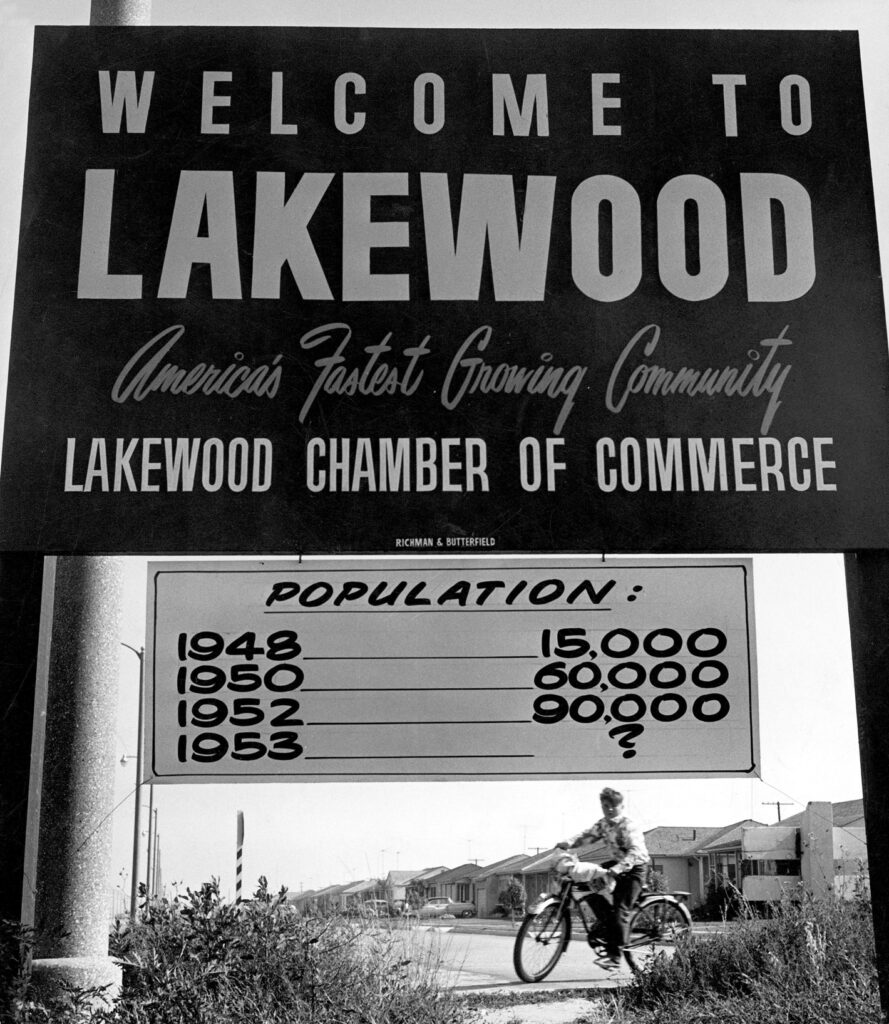

The single-family promise might be best embodied in Lakewood, California circa 1949. Acres of bean fields gave way to a carpet of cookie-cutter, single-family homes. Similar to other proliferating subdivisions, Lakewood transformed from a rural to suburban landscape and filled with middle-class families. Adjusted for inflation, the city’s more than 17,000 homes were built for approximately $96 per square foot and sold for the equivalent of $140,000 in 2019 dollars.1

At that price, they would be affordable to families at or below a $45,000 income level, and well below 50 percent of the current median income for Los Angeles. But today, the median home’s sale price in Lakewood is $600,000, thus only affordable to families at 120 percent of the median income.2 Additionally, at the time of construction, homes were built at a rate of 17 per day—or more than 500 per month—meaning this one community in 1950 built more homes than the entire city of Los Angeles built in 2018.3 It has been well documented that the days of the starter home are over and the affordability and efficiency achieved at Lakewood constitute success even the most ardent modular proselytizer could not dream of.

Without some form of subsidy, affordable newly built housing—whether to rent or own—for low- and middle-income families is a distant memory. Further, our main method for producing social housing, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), is not typically affordable for families earning the federal minimum or even living wages.4 A study has found that there is no county in the country where those households could afford a home without being rent burdened, a new and disturbing phenomenon.5 The affordability of housing in the middle of the 20th century can be credited to a combination of rising wages, available land, federal policies, and high productivity which is hard to fathom in our current world, where more than 40 percent of American workers earn less than $18,000 per year.6

The US was producing public housing in the middle of the 20th century, but the total units built were dwarfed by privately built, single-family homes loaded with hidden subsidies and tax breaks from the GI Bill to the mortgage interest deduction. Add the wraparound services of new infrastructure, good schools, and cheap oil to the built-in incentives, and it is clear that single-family “market rate” developments are our highly subsidized 20th-century social housing success story.7 In terms of environmental sustainability, racial equity, and income diversity, many would not want to copy the sprawling patterns and redlining that defined that era,8 but it is instructive for thinking about where we are now and how we might re-create the broad level of affordability and wealth of that time.

The dominance of the mid-century, single-family housing stock is now hindering housing affordability for a significant percentage of the population. This, our most prevalent type of housing, faces a triple threat to its long-running promise of providing housing stability, the accumulation of wealth, upward mobility, and equity. These threats include a shift to investor-owned, single-family rentals, historically low new supply, and sluggish wage growth. These threats will be further exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. We need to rethink the pathways to housing stability and reformat the lingering policies formulated for the era of Lakewood that no longer benefit a significant segment of the American workforce.

In many markets, families are now outmatched and outmaneuvered by investors who have moved into single-family portfolio purchases since the 2008 housing crisis. Investors bought more than one in five houses in the “starter home” category in the US in 2018 and tend to aggressively raise rents over time.9 In 2019, more than 35 percent of home purchases were to absentee owners rather than owner occupiers.

In Detroit neighborhoods such as Warrendale—in similar houses on similar blocks—the deleterious effects of predatory equity, speculation, and home flippers’ search for returns has created vacancy, abandonment, neglect, and a perplexing array of prices and housing tenure types. In the same block you will find investment properties, homeowners, renters, land contract holders, and agency holdings. Also, on these blocks, houses can sell for anywhere from $1 to $60,000 and change hands three times in a year. In many cases the condition of the house is decoupled from the sales price. This dizzying array of prices and tenure types has diminished the stability, quality of life, and health of the neighborhood.

In Warrendale, the city of Detroit, and the country in general, the percentage of renters is steadily rising with a corresponding decline in homeownership. Indications are that these patterns will not only continue but accelerate and spread to currently stable markets. Between debt-burdened millennials and retiring baby boomers, vast swaths of currently stable, single-family neighborhoods could be degraded, snapped up by investors, and disrupted in the ways we are seeing in limited pockets around the country now.10 The spread out, suburban nature of these neighborhoods precludes tenant organizing and mechanisms like rent control, which are currently being revived in urban areas.11 While renting might be the only option for households in a stagnant wage environment, we should consider ways to make that housing more stable, less predatory, and permanently affordable as it cycles through our governmental agencies and regulated banks.

Banks, Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), and land bank authorities dispose of their single-family portfolios to the highest bidders or well-connected fund managers.12 Sometimes trading for pennies on the dollar, these sales often represent a lost opportunity for large-scale, long-term affordability. Taking the houses or mortgages controlled by Community Reinvestment Act–regulated banks, municipalities, and GSEs out of the speculative market and into the hands of socially motivated, community-based investors would present an alternative to the highly competitive and relatively expensive LIHTC market. Combined with legislation such as the District of Columbia’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act,13 community-based investment would acknowledge the public costs already paid in tax incentives, work outs, and disrupted families and acquire and stabilize a nationwide, distributed network of social housing.

However, treating our growing inventory of troubled single-family assets as social housing in isolation might not produce the results we desire. Unlike with the public housing of the mid-20th century, a suite of wraparound services, a rethinking of zoning and tax policies, and a commitment to ongoing maintenance could be crafted to provide innovation, coherence, and stability to an asset class in the midst of disruption. As a society, we paid for all of our single-family subdivisions and we paid again and again through the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s and the mortgage crisis of the early 2000s.14 Generally, investors gain, and owner occupiers lose. With the economic shock of the global pandemic we are at risk, once again, of using a crisis to redistribute wealth and assets upward, as we did in past housing crises and in programs like the Troubled Asset Relief Program. But the ever worsening economic crisis along with a sustained focus on racial inequalities make this the time to acknowledge past harm and be smart, forward-thinking, and equitable.

While single-family detached housing is not an ideal solution for achieving a multitude of goals from walkability to sustainability to efficiency, it could be another tool for providing some relief to a housing crisis that our current tools can’t seem to solve. Additionally, diversifying the typologies we associate with social housing and healing the original sins of our single-family suburbs is reason enough to try.

MARC NORMAN is the founder of consulting firm Ideas and Action and associate professor of practice at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning. Teaching courses in real estate finance and economic development, he also advises municipal, private, and nonprofit clients on housing and development.